| Revision as of 23:01, 26 May 2014 editOhnoitsjamie (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Administrators261,457 editsm Reverted edits by 101.57.228.60 (talk) to last version by Ohnoitsjamie← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:38, 9 January 2025 edit undoTenebre.Rosso.Sangue995320 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers1,611 edits Reverting edit(s) by 2A00:23C7:8284:6701:ADFB:E4EC:7923:3635 (talk) to rev. 1262078756 by Revirvlkodlaku: Vandalism (RW 16.1)Tags: RW Undo | ||

| (602 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Buddhist views on the belief in a creator deity, or any eternal divine personal being}} | |||

| {{Technical|date=March 2023}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2023}} | |||

| {{Buddhism}} | {{Buddhism}} | ||

| {{Conceptions of God|narrow}} | |||

| ] rejected the existence of a ],<ref>{{cite web|last=Thera|first=Nyanaponika|title=Buddhism and the God-idea|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nyanaponika/godidea.html|work=The Vision of the Dhamma|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society|location=Kandy, Sri Lanka|quote=In Buddhist literature, the belief in a creator god (issara-nimmana-vada) is frequently mentioned and rejected, along with other causes wrongly adduced to explain the origin of the world; as, for instance, world-soul, time, nature, etc. God-belief, however, is placed in the same category as those morally destructive wrong views which deny the kammic results of action, assume a fortuitous origin of man and nature, or teach absolute determinism. These views are said to be altogether pernicious, having definite bad results due to their effect on ethical conduct.}}</ref><ref>''Approaching the Dhamma: Buddhist Texts and Practices in South and Southeast Asia'' by Anne M. Blackburn (editor), Jeffrey Samuels (editor). Pariyatti Publishing: 2003 ISBN 1-928706-19-3 pg 129</ref> refused to endorse many views on creation<ref>{{cite book|title=The All Embracing Net of Views: Brahmajala Sutta|year=2007|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.01.0.bodh.html|author=Bhikku Bodhi|editor=Access To Insight|location=Kandy, Sri Lanka|chapter=III.1, III.2, III.5}}</ref> and stated that questions on the origin of the world are not ultimately useful for ending ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Acintita Sutta: Unconjecturable|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.077.than.html|work=AN 4.77|publisher=Access To Insight|author=Thanissaro Bhikku|language=translated from Pali into English|year=1997|quote=Conjecture about the world is an unconjecturable that is not to be conjectured about, that would bring madness & vexation to anyone who conjectured about it.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Cula-Malunkyovada Sutta: The Shorter Instructions to Malunkya|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.063.than.html|publisher=Access To Insight|author=Thanissaro Bhikku|language=translated from Pali into English|year=1998|quote=It's just as if a man were wounded with an arrow thickly smeared with poison. His friends & companions, kinsmen & relatives would provide him with a surgeon, and the man would say, 'I won't have this arrow removed until I know whether the man who wounded me was a noble warrior, a priest, a merchant, or a worker.' He would say, 'I won't have this arrow removed until I know the given name & clan name of the man who wounded me... until I know whether he was tall, medium, or short... The man would die and those things would still remain unknown to him. In the same way, if anyone were to say, 'I won't live the holy life under the Blessed One as long as he does not declare to me that 'The cosmos is eternal,'... or that 'After death a Tathagata neither exists nor does not exist,' the man would die and those things would still remain undeclared by the Tathagata.}}</ref> | |||

| Generally speaking, ] is a religion that does not include the belief in a ] ].<ref name="Harvey, Peter 2019 p. 1">Harvey, Peter (2019). ''"Buddhism and Monotheism",'' p. 1. Cambridge University Press.</ref>{{sfn|Taliaferro|2013|p=35}}<ref>{{cite book|last1=Blackburn|first1=Anne M.|last2=Samuels|first2=Jeffrey|title=Approaching the Dhamma: Buddhist Texts and Practices in South and Southeast Asia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ktWAQAk7XPkC|year=2003|publisher=Pariyatti|isbn=978-1-928706-19-9|pages=|chapter=II. Denial of God in Buddhism and the Reasons Behind It|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ktWAQAk7XPkC&pg=PA128DQ}}{{Dead link|date=December 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> As such, it has often been described as either (non-]) ] or as ]. However, other scholars have challenged these descriptions since some forms of Buddhism do posit different kinds of ], ], and unconditioned ] (e.g., ]).<ref>Schmidt-Leukel (2006), pp. 1-4.</ref> | |||

| ], instead, emphasizes the system of causal relationships underlying the universe ('']'' or Dependent Origination) which constitute the natural order ('']'') and source of enlightenment. No dependence of phenomena on a supernatural reality is asserted in order to explain the behaviour of matter. According to the doctrine of the Buddha, a human being must study nature ('']'') in order to attain personal wisdom ('']'') regarding the nature of things (''dharma''). In Buddhism, the sole aim of spiritual practice is the complete alleviation of ] in '']'',<ref>{{cite web|title=Alagaddupama Sutta: The Water-Snake Simile|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.022.than.html#dukkha|publisher=Access To Insight|author=Thanissaro Bhikku|language=translated from Pali into English|year=2004|quote=Both formerly and now, monks, I declare only stress and the cessation of stress.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Anuradha Sutta: To Anuradha|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn22/sn22.086.than.html|publisher=Access To Insight|author=Thanissaro Bhikku|language=translated from Pali into English|year=2004|quote=Both formerly & now, it is only stress that I describe, and the cessation of stress.}}</ref> which is called '']''. | |||

| Buddhist teachings state that there are divine beings called '']'' (sometimes translated as 'gods') and other ], heavens, and rebirths in its doctrine of ], or cyclical rebirth. Buddhism teaches that none of these gods is a creator or an eternal being. However, they can live very long lives.<ref name="Harvey, Peter 2019 p. 1"/><ref name=":3" /> In Buddhism, the devas are also trapped in the cycle of rebirth and are not necessarily virtuous. Thus, while Buddhism includes multiple "gods", its main focus is not on them. Peter Harvey calls this "trans-]".<ref name="Harvey, Peter 2019 p. 1"/> | |||

| Some teachers tell students beginning ] that the notion of divinity is not incompatible with Buddhism,<ref>{{cite book|title=Beginning Insight Meditation and other essays|year=1988|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society|pages=Bodhi Leaves|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/figen/bl085.html|author=Dorothy Figen|location=Kandy, Sri Lanka|chapter=Is Buddhism a Religion?|quote=So to these young Christians I can say, "Believe in Christ if you wish, but remember, Jesus never claimed divinity either." Yes, believe in a unitary God, too, if you wish, but cease your imploring, pleading for personal dispensations, health, wealth, relief from suffering. Study the Eightfold Path. Seek the insights and enlightenment that come through meditative learnings. And find out how to achieve for yourself what prayer and solicitation of forces beyond you are unable to accomplish.}}</ref> and at least one Buddhist scholar has indicated that describing Buddhism as ] may be overly simplistic;<ref>Dr. B. Alan Wallace, 'Is Buddhism Really Non-Theistic?' Lecture given at the National Conference of the American Academy of Religion, Boston, Mass., Nov. 1999, p. 8.</ref> but many traditional theist beliefs are considered to pose a hindrance to the attainment of ''nirvana'',<ref>{{cite book|title=Buddhism and the God-idea|year=1994|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society|location=Kandy, Sri Lanka|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nyanaponika/godidea.html|author=Nyanaponika Thera|work=The Vision of the Dhamma|quote=Although belief in God does not exclude a favorable rebirth, it is a variety of eternalism, a false affirmation of permanence rooted in the craving for existence, and as such an obstacle to final deliverance.}}</ref> the highest goal of Buddhist practice.<ref>Mahasi Sayadaw,, The Wheel Publication No. 298/300, Kandy BPS, 1983, "...when Buddha-dhamma is being disseminated, there should be only one basis of teaching relating to the Middle Way or the Eightfold Path: the practice of ], ], and ], and the ]."</ref> | |||

| ] also posit that mundane deities, such as ], are misconstrued to be creators.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-8}} ] follows the doctrine of ], whereby all phenomena arise in dependence on other phenomena, hence no primal unmoved mover could be acknowledged or discerned. ], in the ], is also shown as stating that he saw no single beginning to the universe.<ref name="Harvey, Peter 2019 p. 1"/> | |||

| Despite this apparent nontheism, Buddhists consider ] of the ]<ref>Buddhists consider an enlightened person, the Dhamma and the community of monks as noble. See ].</ref> very important,<ref>{{cite book|last=Thera|first=Nyanaponika|title=Devotion in Buddhism|year=1994|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy, Sri Lanka|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/nyanaponika/devotion.html|quote=It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that the Buddha disparaged a reverential and devotional attitude of mind when it is the natural outflow of a true understanding and a deep admiration of what is great and noble.}}</ref> although the two main traditions of Buddhism differ mildly in their reverential attitudes. While ] view the Buddha as a human being who attained ] or ], through human efforts,<ref>{{cite web|last=Bhikku|first=Thanissaro|title=The Meaning of the Buddha's Awakening|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/awakening.html|publisher=Access to Insight|accessdate=June 5, 2010}}</ref> some ] consider him an embodiment of the cosmic '']'', born for the benefit of others.<ref>{{cite book|title=Becoming the Buddha: The Ritual of Image Consecration in Thailand|year=2004|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-11435-4|author=Donald K. Swearer}}</ref> In addition, some Mahayana Buddhists worship their chief ], ],<ref>{{cite book|last=Hong|first=Xiong|title=Hymn to Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara|year=1997|publisher=Vastplain|isbn=978-957-9460-89-7|location=Taipei}}</ref> and hope to embody him.<ref>{{cite book|title=Becoming the Compassion Buddha: Tantric Mahamudra for Everyday Life|year=2003|publisher=Wisdom Publications|isbn=978-0-86171-343-1|pages=89–110|author=Lama Thubten Yeshe|author2=Geshe Lhundub Sopa|editor=Robina Courtin|month=June}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], Buddhist philosophers like ] developed extensive refutations of ] and ]. Because of this, some modern scholars, such as ], have described this later stage of Buddhism as ]<ref name=":3" /><ref>Schmidt-Leukel (2006), p. 9.</ref> Buddhist anti-theistic writings were also common during the ], in response to the presence of ]aries and their ]. | |||

| Some Buddhists accept the existence of beings in higher realms (see ]), known as ], but they, like humans, are said to be suffering in '']'',<ref>{{cite web|title=The Thirty-one planes of Existence|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/ptf/dhamma/sagga/loka.html|publisher=Access To Insight|accessdate=May 26, 2010|author=John T Bullitt|year=2005|quote=The suttas describe thirty-one distinct "planes" or "realms" of existence into which beings can be reborn during this long wandering through samsara. These range from the extraordinarily dark, grim, and painful hell realms to the most sublime, refined, and exquisitely blissful heaven realms. Existence in every realm is impermanent; in Buddhist cosmology there is no eternal heaven or hell. Beings are born into a particular realm according to both their past kamma and their kamma at the moment of death. When the kammic force that propelled them to that realm is finally exhausted, they pass away, taking rebirth once again elsewhere according to their kamma. And so the wearisome cycle continues.}}</ref> and are not necessarily wiser than us. In fact, the Buddha is often portrayed as a teacher of the gods,<ref>{{cite book|title=Teacher of the Devas|year=1997|publisher=Buddhist Publication Society|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/jootla/wheel414.html|author=Susan Elbaum Jootla|editor=Access To Insight|location=Kandy, Sri Lanka|chapter=II. The Buddha Teaches Deities|quote="Many people worship Maha Brahma as the supreme and eternal creator God, but for the Buddha he is merely a powerful deity still caught within the cycle of repeated existence. In point of fact, "Maha Brahma" is a role or office filled by different individuals at different periods." "His proof included the fact that "many thousands of deities have gone for refuge for life to the recluse Gotama" (MN 95.9). Devas, like humans, develop faith in the Buddha by practicing his teachings." "A second deva concerned with liberation spoke a verse which is partly praise of the Buddha and partly a request for teaching. Using various similes from the animal world, this god showed his admiration and reverence for the Exalted One.", "A discourse called Sakka's Questions (DN 21) took place after he had been a serious disciple of the Buddha for some time. The sutta records a long audience he had with the Blessed One which culminated in his attainment of stream-entry. Their conversation is an excellent example of the Buddha as "teacher of devas," and shows all beings how to work for Nibbana."}}</ref> and superior to them.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bhikku|first=Thanissaro|title=Kevaddha Sutta|year=1997|publisher=Access To Insight|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/dn/dn.11.0.than.html#bigbrahma|authorlink=Digha Nikaya, 11|quote=When this was said, the Great Brahma said to the monk, 'I, monk, am Brahma, the Great Brahma, the Conqueror, the Unconquered, the All-Seeing, All-Powerful, the Sovereign Lord, the Maker, Creator, Chief, Appointer and Ruler, Father of All That Have Been and Shall Be... That is why I did not say in their presence that I, too, don't know where the four great elements... cease without remainder. So you have acted wrongly, acted incorrectly, in bypassing the Blessed One in search of an answer to this question elsewhere. Go right back to the Blessed One and, on arrival, ask him this question. However he answers it, you should take it to heart.}}</ref> Despite this there are believed to be enlightened devas.<ref>http://www.himalayanart.org/pages/Visual_Dharma/yidams.html</ref> | |||

| Despite this, some writers, such as ] and ], have noted that certain doctrines in ] can be seen as being similar to certain theistic doctrines like ] theology and ].<ref>B. Alan Wallace, "". Snow Lion Newsletter, Volume 15, Number 1, Winter 2000. {{ISSN|1059-3691}}.</ref> Various scholars have also compared ] doctrines regarding the supreme and eternal Buddhas like ] or Amitabha with certain forms of theism, such as pantheism and ].<ref>Zappulli, Davide Andrea (2022). ''Towards a Buddhist theism.'' Religious Studies, First View, pp. 1 – 13. {{doi|10.1017/S0034412522000725}}</ref> | |||

| Some variations of Buddhism express a philosophical belief in an ]: a representation of omnipresent enlightenment and a symbol of the true nature of the universe. The primordial aspect that interconnects every part of the universe is the clear light of the eternal Buddha, where everything timelessly arises and dissolves.<ref>http://hhdl.dharmakara.net/hhdlquotes22.html</ref><ref>Dr. Guang Xing, The Concept of the Buddha, RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2005, p. 89</ref><ref>Hattori, Sho-on (2001). A Raft from the Other Shore : Honen and the Way of Pure Land Buddhism. Jodo Shu Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 4-88363-329-2.</ref> | |||

| ==Early |

==Early Buddhist texts== | ||

| ] Brahma Sahampati asks the Buddha to teach. Buddhism accepts the existence of devas (celestial beings, literally "shining ones"), but these beings are not creator gods, nor are they eternal (they suffer and die).]] | |||

| As scholar Surian Yee describes, "the attitude of the Buddha as portrayed in the ]s is more anti-speculative than specifically atheistic", although Gautama did regard the belief in a creator deity to be unhealthy.<ref name="unm.edu">Hayes, Richard P., , ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 9</ref> | |||

| However, the ] placed materialism and amoralism together with ] as forms of wrong view.<ref name="unm.edu"/> | |||

| Damien Keown notes that in the ], the Buddha sees the cycle of rebirths as stretching back "many hundreds of thousands of aeons without discernible beginning."<ref>Keown, Damien (2013). ''"Encyclopedia of Buddhism."'' p. 162. Routledge.</ref> Saṃyutta Nikāya 15:1 and 15:2 states: "This samsara is without discoverable beginning. A first point is not discerned of beings roaming and wandering on hindered by ignorance and fettered by craving."<ref>Bhikkhu Bodhi (2005). ''"In the Buddha's Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon."'' p. 37. Simon and Schuster.</ref> | |||

| As Hayes describes it, "In the Nikaya literature, the question of the existence of God is treated primarily from either an epistemological point of view or a moral point of view. As a problem of epistemology, the question of God's existence amounts to a discussion of whether or not a religious seeker can be certain that there is a greatest good and that therefore his efforts to realize a greatest good will not be a pointless struggle towards an unrealistic goal. And as a problem in morality, the question amounts to a discussion of whether man himself is ultimately responsible for all the displeasure that he feels or whether there exists a superior being who inflicts displeasure upon man whether he deserves it or not... the Buddha Gotama is portrayed not as an atheist who claims to be able to prove God's nonexistence, but rather as a skeptic with respect to other teachers' claims to be able to lead their disciples to the highest good."<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition", ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar) pgs 5-6, 8</ref> | |||

| According to ] ], the early Buddhist ] literature treats the question of the existence of a creator god "primarily from either an epistemological point of view or a moral point of view". In these texts, the Buddha is portrayed not as a creator-denying ] who claims to be able to prove such a god's nonexistence, but rather his focus is other teachers' claims that their teachings lead to the highest good.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., , ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar) pgs 5-6, 8</ref> | |||

| According to Hayes, in the ''Tevijja Sutta'' (DN 13), there is an account of a dispute between two ]s about how best to reach union with Brahma (''Brahmasahavyata''), who is seen as the highest god over whom no other being has mastery and who sees all. However, after being questioned by the Buddha, it is revealed that they do not have any direct experience of this Brahma. The Buddha calls their religious goal laughable, vain, and empty.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition", ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar) p. 2.</ref> | |||

| In the ] the Buddha tells Vasettha that the ] (the Buddha) was ], the 'Truth-body' or the 'Embodiment of Truth', as well as Dharmabhuta, 'Truth-become', 'One who has become Truth.'<ref>]</ref><ref>See Walsh, Maurice. 1995. The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications, “Aggañña Sutta: On Knowledge of Beginnings,” p. 409.</ref> | |||

| Hayes also notes that in the early texts, the Buddha is not depicted as an atheist, but more as a ] who is against religious speculations, including speculations about a creator god. Citing the ''Devadaha Sutta'' (] 101), Hayes states, "while the reader is left to conclude that it is attachment rather than God, actions in past lives, fate, type of birth or efforts in this life that is responsible for our experiences of sorrow, no systematic argument is given in an attempt to disprove the existence of God."<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition", ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar) pp. 9-10</ref> | |||

| The Buddha is equated with the Dhamma: | |||

| {{quote|... and the Buddha comforts him, "Enough, Vakkali. Why do you want to see this filthy body? Whoever sees the Dhamma sees me; whoever sees me sees the Dhamma."<ref>] (SN 22.87) See footnote #3]</ref>}} | |||

| ] also notes that the Buddha specifically calls out the doctrine of ] (termed ]) for criticism in the ]. This doctrine of creation by a supreme lord is defined as follows: "Whatever happiness or pain or neutral feeling this person experiences, all that is due to the creation of a supreme deity (''issaranimmāṇahetu'')."<ref name="Narada Thera 2006 pp. 268-269">Narada Thera (2006) ''"The Buddha and His Teachings,"'' pp. 268-269, Jaico Publishing House.</ref> The Buddha criticized this view because he saw it as a fatalistic teaching that would lead to inaction or laziness: | |||

| ''Putikaya'', the "decomposing" body, is distinguished from the eternal ''Dhamma'' body of the Buddha and the ] body. | |||

| <blockquote>" So, then, owing to the creation of a supreme deity, men will become murderers, thieves, unchaste, liars, slanderers, abusive, babblers, covetous, malicious and perverse in view. Thus for those who fall back on the creation of a god as the essential reason, there is neither desire nor effort nor necessity to do this deed or abstain from that deed."<ref name="Narada Thera 2006 pp. 268-269"/></blockquote> | |||

| ===Brahma in the Pali Canon=== | |||

| ] is among the common gods found in the Pali Canon. Brahma (in common with all other devas) is subject to change, final decline and death, just as are all other sentient beings in ] (the plane of continual reincarnation and suffering). In fact there are several different Brahma worlds and several kinds of Brahmas in Buddhism, all of which however are just beings stuck in samsara for a long while. Sir Charles Eliot describes attitudes towards Brahma in early Buddhism as follows: | |||

| In another early sutta (''Devadahasutta'', ] 101), the Buddha sees the pain and suffering that is experienced by certain individuals as indicating that if they were created by a god, then this is likely to be an evil god:<ref name=":5">Westerhoff, Jan. “Creation in Buddhism” in Oliver, Simon. ''The Oxford Handbook of Creation'', Oxford University Press, Oxford, forthcoming</ref> | |||

| {{quote|There comes a time when this world system passes away and then certain beings are reborn in the "World of Radiance" and remain there a long time. Sooner or later, the world system begins to evolve again and the palace of Brahma appears, but it is empty. Then some being whose time is up falls from the "World of Radiance" and comes to life in the palace and remains there alone. At last he wishes for company, and it so happens that other beings whose time is up fall from the "World of Radiance" and join him. And the first being thinks that he is Great Brahma, the Creator, because when he felt lonely and wished for companions other beings appeared. And the other beings accept this view. And at last one of Brahma’s retinue falls from that state and is born in the human world and, if he can remember his previous birth, he reflects that he is transitory but that Brahma still remains and from this he draws the erroneous conclusion that Brahma is eternal.<ref name="Sir Charles Elliot">{{cite web|url=http://www.gutenberg.org/browse/authors/e#a4887 |title= Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch |author= Sir Charles Elliot | authorlink= Charles Eliot (diplomat)}}</ref>}} | |||

| <blockquote>" If the pleasure and pain that beings feel are caused by the creative act of a Supreme God, then the ] surely must have been created by an evil Supreme God, since they now feel such painful, racking, piercing feelings."</blockquote> | |||

| ===Other common gods referred to in the Canon=== | |||

| Many of the other gods in the Pali Canon find a common mythological role in Hindu literature. Some common gods and goddesses are Indra, Aapo (]), Vayo (]), Tejo (]), Surya, Pajapati (]), Soma, Yasa, Venhu (]), Mahadeva (]), Vijja (]), Usha, Pathavi (]), Sri (]), Kuvera (]), several yakkhas (]s), gandhabbas (]s), ]s, garula (]), sons of Bali, Veroca, etc.<ref>Mahasamaya Sutta, DN 20</ref> While in Hindu texts some of these gods and goddesses are considered embodiments of the Supreme Being, the Buddhist view is that all gods and goddesses were bound to samsara. The world of gods according to the Buddha presents a being with too many pleasures and distractions. | |||

| ===High gods who are mistaken as creator=== | |||

| ==Abhidharma and Yogacara analysis== | |||

| {{further|Brahmā (Buddhism)}} | |||

| The Theravada ] tradition did not tend to elaborate argumentation against the existence of god, but in the '']'' of the ], ] does actively argue against the existence of a creator, stating that the universe has no beginning.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition," ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar) pg 10</ref> | |||

| ] in Bangkok, Thailand.]] | |||

| According to Peter Harvey, Buddhism assumes that the universe has no ultimate beginning to it and thus sees no need for a creator god. In the early texts, the nearest term to this concept is "Great Brahma" (''Maha Brahma''), such as in ''Digha Nikaya'' 1.18.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-8}} However, "hile being kind and compassionate, none of the ''brahmās'' are world-creators."{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=37}} | |||

| The Chinese monk ] studied Buddhism in India during the 7th century CE, staying at ]. There, he studied the Consciousness Only teachings passed down from ] and Vasubandhu, and taught to him by the abbot ]. In his comprehensive work '']'' (Skt. ''Vijñaptimātratāsiddhi Śastra''), Xuanzang refutes the Indian philosophical doctrine of a "Great Lord" (]) or a Great Brahmā, a self-existent and omnipotent creator deity who is ruler of all existence.<ref>Cook, Francis, ''Three Texts on Consciousness Only.'', Numata Center, Berkeley, 1999, pp. 20-21.</ref> | |||

| In the ], Buddhism includes the concept of reborn gods.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-37}} According to this theory, periodically, the physical world system ends and beings of that world system are reborn as ]s in lower heavens. This too ends, according to Buddhist cosmology, and god ] is then born, who is alone. He longs for the presence of others, and the other gods are reborn as his ministers and companions.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-37}} In Buddhist suttas, such as DN 1, Mahabrahma forgets his past lives and falsely believes himself to be the Creator, Maker, All-seeing, the Lord. This belief, state the Buddhist texts, is then shared by other gods. Eventually, however, one of the gods dies and is reborn as human, with the power to remember his previous life.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-8}} He teaches what he remembers from his previous life in lower heaven, that Mahabrahma is the Creator. It is this that leads to the human belief in a creator, according to the Pali Canon.{{sfn|Harvey|2013|p=36-8}} | |||

| {{quote|According to one doctrine, there is a great, self-existent deity whose substance is real and who is all-pervading, eternal, and the producer of all phenomena. This doctrine is unreasonable. If something produces something, it is not eternal, the non-eternal is not all-pervading, and what is not all-pervading is not real. If the deity's substance is all-pervading and eternal, it must contain all powers and be able to produce all phenomena everywhere, at all times, and simultaneously. If he produces phenomena when a desire arises, or according to conditions, this contradicts the doctrine of a single cause. Or else, desires and conditions would arise spontaneously since the cause is eternal. Other doctrines claim that there is a great Brahma, a Time, a Space, a Starting Point, a Nature, an Ether, a Self, etc., that is eternal and really exists, is endowed with all powers, and is able to produce all phenomena. We refute all these in the same way we did the concept of the Great Lord.}} | |||

| ], Malaysia.]] | |||

| ==Mahayana and Vajrayana doctrines== | |||

| A similar story of a high god (brahma) who mistakes himself as the all-powerful creator can be seen in the ''Brahma-nimantanika Sutta'' (MN 49). In this sutta, the Buddha displays his superior knowledge by explaining how a high god named Baka Brahma, who believes himself to be supremely powerful, actually does not know of certain spiritual realms. The Buddha also demonstrates his superior psychic power by disappearing from Baka Brahma's sight, to a realm that he cannot reach, and then challenges him to do the same. Baka Brahma fails in this, demonstrating the Buddha's superiority.<ref name="Nichols, Michael D. 2019 p. 70">Nichols, Michael D. (2019). ''"Malleable Mara: Transformations of a Buddhist Symbol of Evil,"'' p. 70. SUNY Press.</ref> The text also depicts ], an evil trickster figure, as attempting to support the Brahma's misconception of himself. As noted by Michael D. Nichols, MN 49 seems to show that "belief in an eternal creator figure is a devious ploy put forward by the Evil One to mislead humanity, and the implication is that Brahmins who believe in the power and permanence of Brahma have fallen for it."<ref name="Nichols, Michael D. 2019 p. 70"/> | |||

| In the ] tradition, ] advances a number of arguments against the existence of a creator god in his ''Pramāṇavārika'', following in the footsteps of Vasubandhu.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition," ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 12</ref> Later Mahayana scholars such as Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla continued this tradition.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition," ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 14</ref> Some Mahayana and ] traditions of Buddhism, however, do assert an underlying monistic 'ground of being' or ], which is stated to be indestructibly present in all beings and phenomena. The ], in particular, enunciate this view. | |||

| ==The Problem of Evil in the Jatakas== | |||

| ===Tathagatagarbha, Dharmakaya and God=== | |||

| Some stories in the Buddhist ] outline a critique of a Creator deity that is similar to the ]<ref>Harold Netland, Keith Yandell (2009). ''"Buddhism: A Christian Exploration and Appraisal"'', pp. 184 - 186. InterVarsity Press.</ref> | |||

| ], unlike ], talks of the mind using terms such as "]" (''tathagatagarbha''). The affirmation of emptiness by positive terminology is radically different from the early Buddhist doctrines of ] and refusal to personify or objectify any Supreme Reality. | |||

| One Jataka story (VI.208) states: | |||

| In the ''tathagatagarbha'' tradition, the Buddha is on occasion identified with the ], Supreme Reality, which possesses the god-like qualities of eternality, inscrutability and immutability. In his monograph on the tathagatagarbha doctrine as formulated in the only ancient Indian commentarial analysis of the doctrine extant - the ''Uttaratantra'' - Professor C. D. Sebastian writes of how the 'divinised' Buddha is accorded worship and is characterised by a compassionate love, which becomes manifest in the world in the form of salvific activity to liberate beings from suffering. Sebastian stresses, however, that the Buddha thus conceived, although deemed worthy of worship, was never viewed as synonymous to a Creator God: | |||

| <blockquote>If Brahma is lord of the whole world and Creator of the multitude of beings, then why has he ordained misfortune in the world without making the whole world happy; or for what purpose has he made the world full of injustice, falsehood and conceit; or is the lord of beings evil in that he ordained injustice when there could have been justice?<ref>Harold Netland, Keith Yandell (2009). ''"Buddhism: A Christian Exploration and Appraisal"'', pp. 185 - 186. InterVarsity Press.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{quote|"Mahayana Buddhism is not only intellectual, but it is also devotional... in Mahayana, Buddha was taken as God, as Supreme Reality itself that descended on the earth in human form for the good of mankind. The concept of Buddha (as equal to God in theistic systems) was never as a creator but as Divine Love that out of compassion (karuna) embodied itself in human form to uplift suffering humanity. He was worshipped with fervent devotion... He represents the Absolute (''paramartha satya''), devoid of all plurality (''sarva-prapancanta-vinirmukta'') and has no beginning, middle and end... Buddha... is eternal, immutable... As such He represents Dharmakaya."|Professor C. D. Sebastian<ref>Professor C. D. Sebastian, ''Metaphysics and Mysticism in Mahayana Buddhism: An Analytical Study of the Ratnagotravibhago-mahayanaottaratantra-sastram'', ''Bibliotheca Indo-Buddhica'' Series 238, Sri Satguru Publications, Delhi, 2005, pp. 64-66.</ref>}} | |||

| The Pali Bhūridatta Jātaka (No. 543) has the bodhisattva (future Buddha) state: | |||

| According to the Tathagatagarbha sutras, the Buddha taught the existence of this spiritual essence called the tathagatagarbha or ], which is present in all beings and phenomena. Dr. B. Alan Wallace writes of this doctrine: | |||

| : "He who has eyes can see the sickening sight, | |||

| {{quote|"The essential nature of the whole of samsara and nirvana is the absolute space (''dhatu'') of the ''tathagatagarbha'', but this space is not to be confused with a mere absence of matter. Rather, this absolute space is imbued with all the infinite knowledge, compassion, power, and enlightened activities of the Buddha. Moreover, this luminous space is that which causes the phenomenal world to appear, and it is none other than the nature of one's own mind, which by nature is clear light."|Dr. B. Alan Wallace<ref>Dr. B. Alan Wallace, "Is Buddhism Really Non-Theistic?" Lecture delivered at the National Conference of the American Academy of Religion, Boston, Mass., Nov., 1999. sbinstitute.com/.../Is%20Buddhism%20Really%20Nontheistic_.pdf pp. 2-3</ref>}} | |||

| :Why does not Brahmā set his creatures right? | |||

| :If his wide power no limit can restrain, | |||

| :Why is his hand so rarely spread to bless? | |||

| :Why are his creatures all condemned to pain? | |||

| :Why does he not to all give happiness? | |||

| :Why do fraud, lies, and ignorance prevail? | |||

| :Why triumphs falsehood—truth and justice fail? | |||

| :I count you Brahmā one th'unjust among, | |||

| :Who made a world in which to shelter wrong."<ref name="Narada Thera 2006 pp. 268-269"/> | |||

| In the Pali Mahābodhi Jātaka (No. 528), the bodhisattva says: | |||

| Dr. Wallace further writes on how the primal Buddha, Samantabhadra, who in some scriptures is viewed as one with the ''tathagatagarbha'', forms the very radiating foundation of both samsara and nirvana. Noting a progression within Buddhism from doctrines of a mind-stream (''bhavanga'') to that of the absolutised ''tathagatagarbha'', Wallace comments that it may be too simple in the light of such doctrinal elements to define Buddhism unconditionally as "non-theistic": | |||

| :"If there exists some Lord all powerful to fulfil | |||

| {{quote|"], the primordial Buddha whose nature is identical with the ''tathagatagarbha'' within each sentient being, is the ultimate ground of ''samsara'' and ''nirvana''; and the entire universe consists of nothing other than displays of this infinite, radiant, empty awareness. Thus, in light of the theoretical progression from the ''bhavanga'' to the ''tathagatagarbha'' to the primordial wisdom of the absolute space of reality, Buddhism is not so simply non-theistic as it may appear at first glance."|Dr. B. Alan Wallace<ref>Dr. B. Alan Wallace, "Is Buddhism Really Non-Theistic?" Lecture given at the National Conference of the American Academy of Religion, Boston, Mass., Nov. 1999, p. 8.</ref>}} | |||

| :In every creature bliss or woe, and action good or ill; | |||

| :That Lord is stained with sin. | |||

| :Man does but work his will."<ref>Narada Thera (2006) ''"The Buddha and His Teachings,"'' p. 271, Jaico Publishing House.</ref> | |||

| ==Medieval philosophers== | |||

| ===Vajrayana views=== | |||

| While ] was not as concerned with critiquing concepts of God or Īśvara (since ] was not as prominent in India until the medieval era),{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} medieval Indian Buddhists engaged much more thoroughly with the emerging Hindu theisms (mainly by attempting to refute them). According to ], medieval Buddhist philosophers deployed a host of arguments, including the ] and others that "stressed formal problems in the conception of a supreme deity".<ref name=":3">Kapstein, Matthew T. ''The Buddhist Refusal of Theism,'' Diogenes 2005; 52; 61.</ref> Kapstein outlines this second line of argumentation as follows:<ref name=":3" /><blockquote>God, the theists affirm, must be eternal, and an eternal entity must be supposed to be altogether free from corruption and change. That same eternal being is held to be the creator, that is, the causal basis, of this world of corruption and change. The changing state, however, of a thing that is caused implies there to be change also in its causal basis, for a changeless cause cannot explain alteration in the result. The hypothesis of a creator god, therefore, either fails to explain our changing world, or else God himself must be subject to change and corruption, and hence cannot be eternal. Creation, in other words, entails the impermanence of the creator. Theism, the Buddhist philosophers concluded, could not as a system of thought be saved from such contradictions.</blockquote> Kapstein also notes that by this time, "Buddhism's earlier refusal of theism had indeed given way to a well-formed ]." However, Kapstein notes that these criticisms remained mostly philosophical, since Buddhist antitheism "was conceived primarily in terms of the logical requirements of Buddhist philosophical systems, for which the concept of a personal god violated the rational demands of an impersonal, moral and causal order".<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In some Mahayana traditions, the Buddha is indeed worshipped as a virtual divinity who is possessed of supernatural qualities and powers. Dr. Guang Xing writes: "The Buddha worshiped by Mahayanist followers is an omnipotent divinity endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities ... is described almost as an omnipotent and almighty godhead.".<ref>Guang Xing, ''The Three Bodies of the Buddha: The Origin and Development of the Trikaya Theory'', RoutledgeCurzon, Oxford, 2005, pp.1 and 85</ref> | |||

| ===Madhyamaka philosophers=== | |||

| The Buddhist scholar B. Alan Wallace has also indicated (as shown above) that saying that Buddhism as a whole is "non-theistic" may be an over-simplification. Wallace discerns similarities between some forms of Vajrayana Buddhism and notions of a divine "ground of being" and creation. He writes: "a careful analysis of Vajrayana Buddhist cosmogony, specifically as presented in the Atiyoga tradition of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, which presents itself as the culmination of all Buddhist teachings, reveals a theory of a transcendent ground of being and a process of creation that bear remarkable similarities with views presented in Vedanta and Neoplatonic Western Christian theories of creation."<ref>B. Alan Wallace, "Is Buddhism Really Non-Theistic?" Lecture delivered at the National Conference of the American Academy of Religion, Boston, Mass., November 1999. sbinstitute.com/.../Is%20Buddhism%20Really%20Nontheistic_.pdf p. 1, accessed 14 August 2009</ref> In fact, Wallace sees these views as so similar that they seem almost to be different manifestations of the same theory. He further comments: "Vajrayana Buddhism, Vedanta, and Neoplatonic Christianity have so much in common that they could almost be regarded as varying interpretations of a single theory."<ref>B. Alan Wallace, "Is Buddhism Really Non-Theistic?", p. 7</ref> | |||

| In the ''Twelve Gate Treatise (''十二門論, ''Shih-erh-men-lun)'', the Buddhist philosopher ] (c. 1st–2nd century) works to refute the belief of certain Indian non-Buddhists in a god called Isvara, who is "the creator, ruler and destroyer of the world".<ref>Hsueh-Li Cheng. "Nāgārjuna's Approach to the Problem of the Existence of God" in Religious Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Jun. 1976), pp. 207-216 (10 pages), Cambridge University Press.</ref> Nagarjuna makes several arguments against a creator God, including the following:<ref>Hsueh-li Cheng (1982). ''Nagarjuna's Twelve Gate Treatise'', pp. 93-99. D. Reidel Publishing Company</ref> | |||

| * "If all living beings are the sons of God, He should use happiness to cover suffering and should not give them suffering. And those who worship Him should not have suffering but should enjoy happiness. But this is not true in reality." | |||

| * "If God is self-existent, He should need nothing. If He needs something, He should not be called self-existent. If He does not need anything, why did He change, like a small boy who plays a game, to make all creatures?" | |||

| * "Again, if God created all living beings, who created Him? That God created Himself, cannot be true, for nothing can create itself. If He were created by another creator, He would not be self-existent." | |||

| * "Again, if all living beings come from God, they should respect and love Him just as sons love their father. But actually this is not the case; some hate God and some love Him." | |||

| * "Again, if God is the maker , why did He not create men all happy or all unhappy? Why did He make some happy and others unhappy? We would know that He acts out of hate and love, and hence is not self-existent. Since He is not self-existent, all things are not made by Him." | |||

| In his ''Hymn to the Inconceivable'' (''Acintyastava''), Nagarjuna attacks this belief in two verses:<ref>Lindtner, Christian (1986). ''Master of Wisdom: Writings of the Buddhist Master Nāgārjuna'', pp. 26-27. Dharma Pub.</ref><blockquote>33. Just as the work of a magician is empty of substance, all the rest of the world has been said by you to be empty of substance—including a creator deity. | |||

| 34. If the creator is created by another, he cannot avoid being created and, consequently, is not permanent. Alternatively, if he creates himself, it implies that the creator is the agent of the activity affecting himself, which is absurd.</blockquote>Nagarjuna also argues against a Creator in his ''Bodhicittavivaraṇa''.<ref name=":5" /> Furthermore, in his ''Letter to a Friend'', he also rejects the idea of a creator deity:<ref> by Nagarjuna , translated by Alexander Berzin, studybuddhism.com</ref><blockquote> The ] (come) not from a triumph of wishing, not from (permanent) <abbr>time</abbr>, not from <abbr>primal matter</abbr>, not from an <abbr>essential nature</abbr>, not from the Powerful Creator Ishvara, and not from having no <abbr>cause</abbr>. Know that they <abbr>arise</abbr> from <abbr>unawareness</abbr>, karmic actions, and <abbr>craving</abbr>.</blockquote> | |||

| The Tibetan monk-scholar ] of the Tibetan Jonang tradition speaks of a universal spiritual essence or ''noumenon'' (the Buddha as '']'') which contains all sentient beings in their totality, and quotes from the ''Sutra on the Inconceivable Mysteries of the One-Gone-Thus'': | |||

| ] (c. 500 – c. 578) also critiques the idea in his ''Madhyamakahṛdaya'' (Heart of the Middle Way, ch. III).<ref>Schmidt-Leukel, Perry (2016). ''Buddhism, Christianity and the Question of Creation: Karmic or Divine?'' p. 25. Routledge</ref> | |||

| "... space dwells in all appearances of forms .. similarly, the body of the one-gone-thus also thoroughly dwells in all appearances of sentient beings ... For example, all appearances of forms are included inside space. Similarly, all appearances of sentient beings are included inside the body of the one-gone-thus ."<ref>''Dolpopa in Mountain Doctrine: Tibet's Fundamental Treatise on Other-Emptiness and the Buddha Matrix'', ed. and translated by Jeffrey Hopkins, Ithaca, N.Y. 2006, p. 84</ref> | |||

| A later Madhyamaka philosopher, ], states in his ''Introduction to the Middle Way'' (6.114): "Because things (bhava) are not produced without a cause (hetu), from a creator god (isvara), from themselves, another or both, they are always produced in dependence ."<ref>Fenner, Peter (2012). ''The Ontology of the Middle Way'', p. 85. Springer Science & Business Media</ref> | |||

| Dolpopa further quotes Buddhist scripture when he writes of this unified spiritual essence or noumenon as the 'supreme Over-Self of all continuums'<ref>Jeffrey Hopkins, ''Mountain Doctrine'', New York, 2006, p. 126</ref> and as "Self always residing in all, as the selfhood of all."<ref>Jeffrey Hopkins, ''Mountain Doctrine'', New York, 2006, p. 135</ref> | |||

| ] (c. 8th century), in the 9th chapter of his '']'', states: | |||

| ===Yogacara and the Absolute=== | |||

| Another scholar sees a Buddhist Absolute in Consciousness. Writing on the ] school of Buddhism, Dr. A. K. Chatterjee remarks: "The Absolute is a non-dual consciousness. The duality of the subject and object does not pertain to it. It is said to be void (''sunya''), devoid of duality; in itself it is perfectly real, in fact the only reality ...There is no consciousness ''of'' the Absolute; Consciousness ''is'' the Absolute."<ref>Dr. A. K. Chatterjee, ''The Yogacara Idealism'', Motilal, Delhi, 1975, pp. 133-134</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>'God is the cause of the world.' Tell me, who is God? The elements? Then why all the trouble about a mere word? (119) Besides, the elements are manifold, impermanent, without intelligence or activity; without anything divine or venerable; impure. Also such elements as earth, etc., are not God.(120) Neither is space God; space lacks activity, nor is ]—that we have already excluded. Would you say that God is too great to conceive? An unthinkable creator is likewise unthinkable, so that nothing further can be said.<ref name="Dargyay, Eva K 1985">Dargyay, Eva K. "The Concept of a 'Creator God' in Tantric Buddhism". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist studies, Volume 8, 1985, Number 1.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| While this is a traditional Tibetan interpretation of Yogacara views, it has been rejected by modern Western scholarship, namely by Kochumuttom, Anacker, Kalupahana, Dunne, Lusthaus, Powers, and Wayman.<ref>''Empty Words: Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-Cultural Interpretation'' by Jay L. Garfield. Oxford University Press: 2001. ISBN 0-19-514672-7<sup></sup></ref><ref name="acmuller.net">], ''What is and isn't Yogacara.'' .</ref><ref>Alex Wayman, ''A Defense of Yogacara Buddhism.'' Philosophy East and West, Volume 46, Number 4, October 1996, pages 447-476. "Of course, the Yogacara put its trust in the subjective search for truth by way of a samadhi. This rendered the external world not less real, but less valuable as the way of finding truth. The tide of misinformation on this, or on any other topic of Indian lore comes about because authors frequently read just a few verses or paragraphs of a text, then go to secondary sources, or to treatises by rivals, and presume to speak authoritatively. Only after doing genuine research on such a topic can one begin to answer the question: why were those texts and why do the moderns write the way they do?"</ref> Scholar ] writes: "They did not focus on consciousness to assert it as ultimately real (Yogācāra claims consciousness is only conventionally real since it arises from moment to moment due to fluctuating causes and conditions), but rather because it is the cause of the karmic problem they are seeking to eliminate."<ref name="acmuller.net"/> | |||

| === |

===Vasubandhu=== | ||

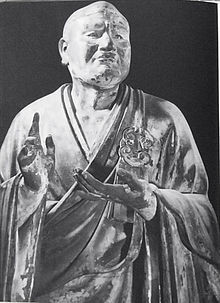

| ], Nara, Japan]] | |||

| A further name for the irreducible, time-and-space-transcending mysterious Truth or Essence of Buddhic Reality spoken of in some Mahayana and tantric texts is the ] (Body of Truth). Of this the ] master ], says:<ref>''Zen Pivots'', Weatherhill, NY, 1998, pp. 142, 146:</ref> | |||

| {{quote|... ''dharmakaya'' the equivalent of God ... The Buddha also speaks of no time and no space, where if I make a sound there is in that single moment a million years. It is spaceless like radio waves, like electric space - intrinsic. The Buddha said that there is a mirror that reflects consciousness. In this electric space a million miles and a pinpoint - a million years and a moment - are exactly the same. It is pure essence ... We call it 'original consciousness' - 'original ''akasha''' - perhaps God in the Christian sense. I am afraid of speaking about anything that is not familiar to me. No one can know what IT is ...}} | |||

| The 5th-century Buddhist philosopher ] argued that a creator's singular identity is incompatible with creating the world in his '']''.<ref name="unm.edu">Hayes, Richard P., , ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 11-15.</ref> He states (AKB, chapter 2):<blockquote> The universe does not originate from one single cause (''ekaṃ kāraṇam'') which may be called God/Supreme Lord (]), Self (]), Primal Source (]) or any other name.</blockquote> Vasubandhu then proceeds to outline various arguments for and against the existence of a creator deity or single cause. In the argument that follows, the Buddhist non-theist begins by stating that if the universe arose from a single cause, "things would arise all at the same time: but everyone sees that they arise successively".<ref name=":0">de La Vallee Poussin & Sangpo (2012), p. 675</ref> The theist responds that things arise in succession because of the power of God's wishes; he thus wills things to arise in succession. The Buddhist responds: "then things do not arise from a single cause, because the desires (of God) are multiple". Furthermore, these desires would have to be simultaneous, but since God is not multiple, things would all arise at the same time.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| The same Zen adept, Sokei-An, further comments:<ref>''The Zen Eye'', Weatherhill, New York, 1994, p. 41</ref> | |||

| {{quote|The creative power of the universe is not a human being; it is Buddha. The one who sees, and the one who hears, is not this eye or ear, but the one who is ''this'' consciousness. ''This One'' is Buddha. ''This One'' appears in every mind. ''This One'' is common to all sentient beings, and is God.}} | |||

| The theist now responds that God's desires are not simultaneous, "because God, in order to produce his desires, takes into account other causes". The Buddhist replies that if this is the case, then God is not the single cause of everything, and furthermore, he then relies on causes that are also dependent on other causes (and so on).<ref name=":1">de La Vallee Poussin & Sangpo (2012), p. 676.</ref> | |||

| The Rinzai Zen Buddhist master, Soyen Shaku, speaking to Americans at the beginning of the 20th century, discusses how in essence the idea of God is not absent from Buddhism, when understood as ultimate, true Reality:<ref>''Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot'', by Soyen Shaku, Samuel Weiser Inc, New York, 1971, pp.25-26, 32</ref> | |||

| {{quote|At the outset, let me state that Buddhism is not atheistic as the term is ordinarily understood. It has certainly a God, the highest reality and truth, through which and in which this universe exists. However, the followers of Buddhism usually avoid the term God, for it savors so much of ], whose spirit is not always exactly in accord with the Buddhist interpretation of religious experience ... To define more exactly the Buddhist notion of the highest being, it may be convenient to borrow the term very happily coined by a modern German scholar, 'panentheism', according to which God is ... all and one and more than the totality of existence .... As I mentioned before, Buddhists do not make use of the term God, which characteristically belongs to Christian terminology. An equivalent most commonly used is ] ... When the Dharmakaya is most concretely conceived it becomes the Buddha, or Tathagata ...}} | |||

| Then the question of why God creates the world is taken up. The theist states that it is for God's own joy. The Buddhist responds that in this case, God is not lord over his own joy since he cannot create it without an external mean, and "if he is not Sovereign with respect to his own joy, how can he be Sovereign with respect to the world?"<ref name=":1" /> Furthermore, the Buddhist also adds:<blockquote> Besides, do you say that God finds joy in seeing the creatures which he has created in the prey of all the distress of existence, including the tortures of the hells? Homage to this kind of God! The profane stanza expresses it well: "One calls him Rudra because he burns, because he is sharp, fierce, redoubtable, an eater of flesh, blood and marrow.<ref name=":2">de La Vallee Poussin & Sangpo (2012), p. 677.</ref></blockquote> Furthermore, the Buddhist states that the followers of God as a single cause deny observable cause and effect. If they modify their position to accept observable causes and effects as auxiliaries to their God, "this is nothing more than a pious affirmation, because we do not see the activity of a (Divine) Cause next to the activity of the causes called ''secondary''".<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ===Primordial Buddhas=== | |||

| {{Main|Eternal Buddha}} | |||

| Theories regarding a self-existent immutable substantial "ground of being" or substrate were common in India prior to the Buddha, and were rejected by him: "The Buddha, however, refusing to admit any metaphysical principle as a common thread holding the moments of encountered phenomena together, rejects the ] notion of an immutable substance or principle underlying the world and the person and producing phenomena out of its inherent power, be it 'being', ], ], or 'god.'"<ref>Noa Ronkin, ''Early Buddhist metaphysics: the making of a philosophical tradition.'' Routledge, 2005 , page 196.</ref> | |||

| The Buddhist also argues that since God did not have a beginning, the creation of the world by God would also not have a beginning (contrary to the claims of the theists). Vasubandhu states: "the Theist might say that the work of God is the creation (''ādisarga''): but it would follow that creation, dependent only on God, would never have a beginning, like God himself. This is a consequence which the Theist rejects."<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| In later Mahayana literature, however, the idea of an eternal, all-pervading, all-knowing, immaculate, uncreated and deathless Ground of Being (the ''dharmadhatu'', inherently linked to the ''sattvadhatu'', the realm of beings), which is the Awakened Mind (''bodhicitta'') or ] ("body of Truth") of the Buddha himself, is attributed to the Buddha in a number of Mahayana sutras, and is found in various tantras as well. In some Mahayana texts, such a principle is occasionally presented as manifesting in a more personalised form as a primordial buddha, such as ], ], ], and ], among others. | |||

| Vasubandhu finishes this section of his commentary by stating that sentient beings wander from birth to birth doing various actions, experiencing the effects of their karma and "falsely thinking that God is the cause of this effect. We must explain the truth in order to put an end to this false conception."<ref>de La Vallee Poussin & Sangpo (2012), p. 678.</ref> | |||

| In Buddhist tantric and Dzogchen scriptures, too, this immanent and transcendent Dharmakaya (the ultimate essence of the Buddha’s being) is portrayed as the primordial Buddha, Samantabhadra, worshipped as the primordial lord. In a study of ], Dr. ] mentions how Samantabhadra Buddha is indeed seen as ‘the heart essence of all buddhas, the Primordial Lord, the noble Victorious One, Samantabhadra’.<ref>Dr. ], ''Approaching the Great Perfection: Simultaneous and Gradual Methods of Dzogchen Practice in the Longchen Nyingtig'', Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2004, p. 55</ref> Dr. Schaik indicates that Samantabhadra is not to be viewed as some kind of separate ''mindstream'', apart from the mindstreams of sentient beings, but should be known as a universal nirvanic principle termed the Awakened Mind (''bodhi-citta'') and present in all.<ref>Dr. Sam van Schaik, ''Approaching the Great Perfection'', Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2004, p. 55</ref> Dr. Schaik quotes from the tantric texts, ''Experiencing the Enlightened Mind of Samantabhadra'' and ''The Subsequent Tantra of Great Perfection Instruction'' to portray Samantabhadra as an uncreated, reflexive, radiant, pure and vital Knowing (gnosis) which is present in all things: | |||

| ===Other Yogacara philosophers=== | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| The Chinese monk ] (fl. c. 602–664) studied Buddhism in India during the seventh century, staying at ]. There, he studied the ] teachings passed down from ] and Vasubandhu and taught to him by the abbot ]. In his work '']'' (Skt. ''Vijñāptimātratāsiddhi śāstra''), Xuanzang refutes a "Great Lord" or Great Brahmā doctrine:<ref>Cook, Francis, Chʿeng Wei Shih Lun (''Three Texts on Consciousness Only''), Numata Center, Berkeley, 1999, {{ISBN|978-1-886439-04-7}}, pp. 20-21.</ref> | |||

| The essence of all phenomena is the awakened mind; | |||

| {{blockquote|According to one doctrine, there is a great, self-existent deity whose substance is real and who is all-pervading, eternal, and the producer of all phenomena. This doctrine is unreasonable. If something produces something, it is not eternal, the non-eternal is not all-pervading, and what is not all-pervading is not real. If the deity's substance is all-pervading and eternal, it must contain all powers and be able to produce all ]s everywhere, at all times, and simultaneously. If he produces dharma when a desire arises, or according to conditions, this contradicts the doctrine of a single cause. Or else, desires and conditions would arise spontaneously since the cause is eternal. Other doctrines claim that there is a great Brahma, a Time, a Space, a Starting Point, a Nature, an Ether, a Self, etc., that is eternal and really exists, is endowed with all powers, and is able to produce all dharmas. We refute all these in the same way we did the concept of the Great Lord.<ref>{{cite book|author=Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research|title=Chʿeng Wei Shih Lun|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qjDYAAAAMAAJ|date=January 1999|publisher=仏教伝道協会|isbn=978-1-886439-04-7|pages=20–22}}</ref>}} The 7th-century Buddhist scholar ] advances a number of arguments against the existence of a creator god in his ''Pramāṇavārtika'', following in the footsteps of Vasubandhu.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition," ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 12</ref> | |||

| the mind of all Buddhas is the awakened mind; | |||

| and the life-force of all sentient beings is the awakened mind, too … | |||

| This unfabricated gnosis of the present moment is the reflexive luminosity, naked and stainless, the Primordial Lord himself.<ref>Dr. Sam van Schaik, ''Approaching the Great Perfection'', Wisdom, Boston, 2004, p. 55</ref>}} | |||

| Later ] scholars, such as ], ], ] (fl. c. 9th or 10th century), and ] (fl. 975–1025), also continued to write and develop the Buddhist anti-theistic arguments.<ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition," ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988:Mar.) pg 14</ref><ref name=":3" /><ref>"Śaṅkaranandana" in Silk, Jonathan A (editor in chief). ''Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism Volume II: Lives.''</ref> | |||

| The ] Buddhist monk, Dohan, regarded the two great Buddhas, ] and ], as one and the same ] Buddha and as the true nature at the core of all beings and phenomena. There are several realisations that can accrue to the Shingon practitioner of which Dohan speaks in this connection, as Dr. James Sanford points out: there is the realisation that ] is the ] Buddha, Vairocana; then there is the realisation that Amida as Vairocana is eternally manifest within this universe of time and space; and finally there is the innermost realisation that Amida is the true nature, material and spiritual, of all beings, that he is 'the omnivalent wisdom-body, that he is the unborn, unmanifest, unchanging reality that rests quietly at the core of all phenomena'.<ref>Dr. James H. Sanford, 'Breath of Life: The Esoteric Nembutsu' in ''Tantric Buddhism in East Asia'', ed. by Dr. Richard K. Payne, Wisdom Publications, Boston, 2006, p. 176</ref> | |||

| The 11th-century Buddhist philosopher ], at the former university at Vikramashila (now Bhagalpur, ]), criticized the arguments for the existence of a God-like being called Isvara that emerged in the ] in his "Refutation of Arguments Establishing Īśvara" (''Īśvara-sādhana-dūṣaṇa''). These arguments are similar to those used by other sub-schools of Hinduism and Jainism that questioned the Navya-Nyaya theory of a dualistic creator.<ref>Parimal G. Patil. ''Against a Hindu God: Buddhist Philosophy of Religion in India''. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. pp. 3-4, 61-66 with footnotes, {{ISBN|978-0-231-14222-9}}.</ref> | |||

| Similar God-like descriptions are encountered in the ''All-Creating King Tantra'' (]), where the universal Mind of Awakening (in its mode as "Samantabhadra Buddha") declares of itself:<ref>''The Supreme Source'', p. 157</ref> | |||

| ===Theravada Buddhists=== | |||

| {{quote|I am the core of all that exists. I am the seed of all that exists. I am the cause of all that exists. I am the trunk of all that exists. I am the foundation of all that exists. I am the root of existence. I am "the core" because I contain all phenomena. I am "the seed" because I give birth to everything. I am "the cause" because all comes from me. I am "the trunk" because the ramifications of every event sprout from me. I am "the foundation" because all abides in me. I am called "the root" because I am everything.}} | |||

| The ] commentator ] also specifically denied the concept of a Creator. He wrote: | |||

| <blockquote>"For there is no god Brahma. The maker of the conditioned world of rebirths. Phenomena alone flow on. Conditioned by the coming together of causes." ('']'' 603).<ref name="Harvey, Peter 2019 p. 1"/> </blockquote><nowiki/> | |||

| The ] presents the great bodhisattva, Avalokitesvara, as a kind of supreme lord of the cosmos. A striking feature of Avalokitesvara in this sutra is his creative power, as he is said to be the progenitor of various heavenly bodies and divinities. Dr. Alexander Studholme, in his monograph on the sutra, writes: | |||

| ==Mahayana and theism== | |||

| {{quote|The sun and moon are said to be born from the bodhisattva's eyes, Mahesvara from his brow, Brahma from his shoulders, Narayana from his heart, Sarasvati from his teeth, the winds from his mouth, the earth from his feet and the sky from his stomach.'<ref>Dr. Alexander Studholme, ''The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra'', SUNY, 2002, p. 40</ref>}} | |||

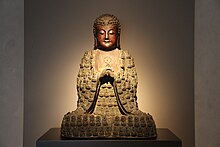

| ], Shanhua Temple, ], China]] | |||

| Mahayana Buddhist traditions have more complex Buddhologies, which often contain a figure variously termed the ], "Supreme Buddha", the One Original Buddha, or ] (primordial Buddha or first Buddha).<ref>Getty, Alice (1988). The Gods of Northern Buddhism: Their History and Iconography, p. 41. Courier Corporation.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Chryssides |first1=George D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WA12nHRtmAwC&q=%22soka+gakkai%22+%22nichiren+shu%22+%22nichiren+shoshu%22&pg=PA251 |title=Historical dictionary of new religious movements |date=2012 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=9780810861947 |edition=2nd |location=Lanham, Md. |page=251}}</ref> | |||

| Avalokitesvara himself is linked in the versified version of the sutra to the first Buddha, the Adi Buddha, who is 'svayambhu' (self-existent, not born from anything or anyone). Dr. Studholme comments: "Avalokitesvara himself, the verse sutra adds, is an emanation of the ''Adibuddha'', or 'primordial Buddha', a term that is explicitly said to be synoymous with ''Svayambhu'' and ''Adinatha'', 'primordial lord'."<ref>Dr. Alexander Studholme, ''The Origins of Om Manipadme Hum: A Study of the Karandavyuha Sutra'', SUNY, 2002, p. 12</ref> | |||

| ===Mahayana buddhology and theism=== | |||

| The Primordial Buddha is ultimately both the individual mind and the immanent ominpresent enlightenment of the macrocosmical reality. The individual and external phenomena being seen as interdependent. | |||

| ], which depicts his body as being composed of numerous other Buddhas.]] | |||

| Mahayana Buddhist interpretations of the Buddha as a ], which is eternal, all-compassionate, and existing on a cosmic scale, have been compared to ] by various scholars. For example, Guang Xing describes the Mahayana Buddha as an ] and almighty divinity "endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities".<ref>Guang Xing (2005). ''The Three Bodies of the Buddha: The Origin and Development of the Trikaya Theory''. Oxford: Routledge Curzon: pp. 1, 85</ref> In Mahayana, a fully awakened Buddha (such as ]) is held to be ] as well as having other qualities, such as infinite wisdom, an immeasurable life, and boundless compassion.<ref>Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 240, 315.</ref> In ], Buddhas are often seen as also having eternal life.<ref>Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 315.</ref> According to Paul Williams, in Mahayana, a Buddha is often seen as "a spiritual king, relating to and caring for the world".<ref name=":822">Williams, Paul, ''Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations,'' Routledge, 2008, p. 27.</ref> | |||

| ===The Eternal Buddha of Shin Buddhism=== | |||

| In ], ] Buddha is viewed as the eternal Buddha who manifested as Shakyamuni in India and who is the personification of Nirvana itself. The Shin Buddhist priest, John Paraskevopoulos, in his monograph on Shin Buddhism, writes: | |||

| Various authors, such as F. Sueki, ], and Fabio Rambelli, have described Mahayana Buddhist views using the term "]" (the belief that God and the universe are identical).<ref>Sueki, F (1996) 日本仏教史―思想史としてのアプローチ (''History of Japanese Buddhism: An Approach from the History of Thought''). Tokyo: Shinchōsha.</ref><ref>Rambelli, Fabio (2013) ''A Buddhist Theory of Semiotics''. London: Bloomsbury Academic.</ref><ref name=":6">Duckworth, Douglas (2015). ''Buddha-nature and the logic of pantheism''. In Powers, J (ed.), The Buddhist World. London: Routledge, pp. 235–247</ref> Similarly, ] has compared Tibetan Buddhist Buddhology with the related view of ].<ref>Samuel, G (2013) ''Panentheism and the longevity practices of Tibetan Buddhism''. In Biernacki, L and Clayton, P (eds), Panentheism across the World's Traditions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 83–99.</ref> | |||

| 'In Shin Buddhism, Nirvana or Ultimate Reality (also known as the "Dharma-Body" or ''Dharmakaya'' in the original Sanskrit) has assumed a more concrete form as (a) the Buddha of Infinite Light (''Amitabha'') and Infinite Life (''Amitayus'')and (b) the "Pure Land" or "Land of Utmost Bliss" (''Sukhavati''), the realm over which this Buddha is said to preside ... Amida is the Eternal Buddha who is said to have taken form as Shakyamuni and his teachings in order to become known to us in ways we can readily comprehend.'<ref>John Paraskevopoulos, ''Call of the Infinite: The Way of Shin Buddhism'', Sophia Perennis Publications, California, 2009, pp. 16 - 17</ref> | |||

| Duckworth draws on positive Mahayana conceptions of ], which he explains as a "positive foundation" and "a pure essence residing in temporarily obscured sentient beings".<ref name=":6" /> He compares various Mahayana interpretations of Buddha-nature (Tibetan and East Asian) with a pantheist view that sees all things as divine and that "undoes the duality between the divine and the world".<ref name=":6" /> In a similar fashion, Eva K. Neumaier compares Mahayana Buddha-nature teachings that point to a source of all things with the theology of ] (1401–1464), who described God as an essence and the world as a manifestation of God.<ref name=":13">Neumaier, Eva K. "Buddhist Forms of Belief in Creation", In Schmidt-Leukel (2006) Buddhism, Christianity and the Question of Creation. 1st Edition. Routledge.</ref> | |||

| John Paraskevopoulos elucidates the notion of Nirvana, of which Amida is an embodiment, in the following terms: | |||

| José Ignacio Cabezón notes that while Mahayana sources reject a universal creator God that stands apart from the world, as well as any single creation event for the entire universe, Mahayanists do accept "localized" creation of specific worlds by the Buddhas and bodhisattvas as well as the idea that any world is jointly created by the collective karmic forces of all the beings who reside in them.<ref name=":11">Cabezón, José Ignacio. "Three Buddhist Views of the Doctrines of Creation and Creator", In Schmidt-Leukel (2006) ''Buddhism, Christianity and the Question of Creation''. 1st Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781315261218</ref> Buddha-created worlds are termed "]" (or "pure lands"), and their creation is seen as a key activity of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.<ref name=":11" /> | |||

| {{quote|... more positive connotation is that of a higher state of being, the dispelling of illusion and the corresponding joy of liberation. An early Buddhist scripture describes Nirvana as: ... the far shore, the subtle, the very difficult to see, the undisintegrating, the unmanifest, the peaceful, the deathless, the sublime, the auspicious, the secure, the destruction of craving, the wonderful, the amazing, the unailing, the unafflicted, dispassion, purity, freedom, the island, the shelter, the asylum, the refuge ... (''Samyutta Nikaya'')<ref>John Paraskevopoulos, Call of the Infinite: The Way of Shin Buddhism, California, 2009, p. 21</ref>}} | |||

| Much comparative work has also been done on Mahayana Buddhist thought and ] ]. Scholars who have worked in this include ], ], ], ], John S. Yokota, Steve Odin, and Linyin Gu.<ref>Gu, L (2005) Dipolarity in Chan Buddhism and the Whiteheadian God. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 32, 211–222.</ref><ref name=":9">McDaniel, J.B.B. (2003). ''Buddhist-Christian Studies'' ''23'', 67-76. {{doi|10.1353/bcs.2003.0024}}</ref><ref name=":10">{{Cite web |last=Cobb Jr |first=John B. |date=2002 |title=Whitehead and Buddhism – Religion Online |url=https://www.religion-online.org/article/whitehead-and-buddhism/ |access-date=12 March 2023}}</ref><ref>Odin, Steve (1982). ''Process Metaphysics and Hua-Yen Buddhism: A Critical Study of Cumulative Penetration vs. Interpretation.'' State University of New York Press.</ref><ref>Griffin, David R. (1974). ''''. International Philosophical Quarterly 14 (3):261-284.</ref><ref>Shen, Vincent. ''Whitehead and Chinese Philosophy: The Ontological Principle and Huayan Buddhism's Concept of shi'' in Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought. {{doi|10.1515/9783110333299.1.613}}</ref><ref>Yokota, John S. ''''. Process Studies Vol. 23, No. 2, Special Issue on Process Thought and Buddhism (SUMMER 1994), pp. 87-97 (11 pages). University of Illinois Press.</ref> Some of these figures have also been involved in ] dialogue.<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":10" /> Cobb sees many affinities with the Buddhist ideas of ] and ] and Whitehead's view of God. He has incorporated these into his own process theology.<ref>Ingram Paul O (2011). ''The Process of Buddhist-Christian Dialogue'', pp. 34-35. ISD LLC.</ref> In a similar fashion, some Buddhist thinkers, like ] and John S. Yokota, have developed Buddhist theologies that draw on process theology.<ref>Hirota, Dennis (editor) (2000) ''Toward a Contemporary Understanding of Pure Land Buddhism: Creating a Shin Buddhist Theology in a Religiously Plural World,'' p. 97. State University of New York Press.</ref> | |||

| This Nirvana is seen as eternal and of one nature, indeed as the essence of all things. Paraskevopoulos tells of how the ''Mahaparinirvana Sutra'' speaks of Nirvana as eternal, pure, blissful and true self: | |||

| ===East Asian Buddhism and theism=== | |||

| {{quote|In Mahayana Buddhism it is taught that there is fundamentally one reality which, in its highest and purest dimension, is experienced as Nirvana. It is also known, as we have seen, as the Dharma-Body (considered as the ultimate form of Being) or "Suchness" (''Tathata'' in Sanskrit) when viewed as the essence of all things ... "The Dharma-Body is eternity, bliss, true self and purity. It is forever free of all birth, ageing, sickness and death" (''Nirvana Sutra'')<ref>Paraskevopoulos, ''Call of the Infinite: The Way of Shin Buddhism'', California, 2009, p. 22</ref>}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In ] Buddhism, the supreme Buddha ] is seen as the "cosmic Buddha", with an infinite body that comprises the entire universe and whose light penetrates every particle in the ].<ref>Cook, Francis Harold (1977). ''Hua-yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra,'' pp. 90-91. Pennsylvania State University Press.</ref> According to a religious pamphlet from ] temple in Japan (the headquarters of Japanese Huayan), "Vairocana Buddha exists everywhere and every time in the Universe, and the Universe itself is his body. At the same time, the songs of birds, the colors of flowers, the currents of streams, the figures of clouds—all these are the sermon of Buddha".<ref>Cook, Francis Harold (1977). ''Hua-yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra,'' p. 91. Pennsylvania State University Press.</ref> However, Francis Cook argues that Vairocana is not a god, nor has the functions of a monotheistic god, since he is not a creator of the universe, nor a judge or father who governs the world.<ref name=":8">Cook, Francis Harold (1977). ''Hua-yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra,'' pp. 91-94. Pennsylvania State University Press.</ref> | |||

| To attain this Self, however, it is needful to transcend the 'small self' and its pettiness with the help of an 'external' agency, Amida Buddha. This is the view promulgated by the ] founding Buddhist master, ]. John Paraskevopoulos comments on this: | |||

| ], meanwhile, has written that the idea of the Buddha's "cosmic body", who is both the cosmos and its creator, "is very close to the idea of God in the theistic religions".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Thich Nhat Hanh |date=26 June 2015 |title=Connecting to Our Root Teacher, the Buddha |url=https://plumvillage.org/about/thich-nhat-hanh/letters/connecting-to-our-root-teacher-a-letter-from-thay-27-sept-2014/ |access-date=24 March 2023 |website=Plum Village}}</ref> Similarly, Lin Weiyu writes that the Huayan school interprets Vairocana as "omnipresent, omnipotent and identical to the universe itself".<ref name=":03">LIN Weiyu 林威宇 (UBC): Vairocana of the ''Avataṃsaka Sūtra'' as Interpreted by Fazang 法藏 (643-712): A Comparative Reflection on "Creator" and "Creation" 法藏(643-712)筆下《華嚴經》中的盧舍那:談佛教中的創世者和創世</ref> According to Lin, the Huayan commentator ]'s conception of Vairocana contains "elements that approach Vairocana to the monotheistic God".<ref name=":03" /> However, Lin also notes that this Buddha is contained within a broader Buddhist metaphysics of ], which tempers the reification of this Buddha as a monotheistic creator god.<ref name=":03" /> | |||

| {{quote|Shinran's great insight was that we cannot conquer the self by the self. Some kind of external agency is required: (a) to help us to shed light on our ego as it really is in all its petty and baneful guises; and (b) to enable us to subdue the small 'self' with a view to realising the Great Self by awakening to Amida's light.<ref>John Paraskevopoulos, ''The Call of the Infinite: The Way of Shin Buddhism'', California, 2009, p. 43</ref>}} | |||

| The ] Buddhist view of the Supreme Buddha ], whose body is seen as being the whole universe, has also been called "]" (the idea that the cosmos is God) by scholars like Charles Eliot, ], and Masaharu Anesaki.<ref>Eliot, Charles (2014). ''Japanese Buddhism,'' p. 340. Routledge.</ref><ref>Hajime Nakamura (1992). ''A Comparative History of Ideas'', p. 434. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.</ref><ref>Masaharu Anesaki (1915). ''Buddhist Art in Its Relation to Buddhist Ideals,'' p. 15. Houghton Mifflin.</ref> Fabio Rambelli terms it a kind of pantheism, the main doctrine of which is that Mahāvairocana's ] is co-substantial with the universe and is the very substance that the universe consists of. Furthermore, this cosmic Buddha is seen as making use of all the sounds, thoughts, and forms in the universe to preach the Buddha's teaching to others. Thus, all forms, thoughts, and sounds in the universe are seen as manifestations and teachings of the Buddha.<ref>Teeuwen, M. (2014). . ''Monumenta Nipponica'' ''69''(2), 259-263. {{doi|10.1353/mni.2014.0025}}</ref> | |||

| When that Great Self of Amida's light is realised, Shin Buddhism is able to see the Infinite which transcends the care-worn mundane. John Paraskevopoulos concludes his monograph on Shin Buddhism thus: | |||

| ===Tantric Adi-Buddha theory and theism=== | |||

| {{quote|It is time we discarded the tired view of Buddhism as a dry and forensic rationalism , lacking in warmth and devotion ... By hearing the call of Amida Buddha we become awakened to true reality and its unfathomable working ... to live a life that dances jubilantly in the resplendent light of the Infinite.<ref>John Paraskevopoulos, ''The Call of the Infinite: The Way of Shin Buddhism'', California, 2009, p. 81</ref>}} | |||

| ] Samantabhadra, a symbol of the ] in ] thought]] | |||