| Revision as of 06:05, 4 January 2014 editAnythingyouwant (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Template editors91,260 edits →Political arguments: add← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:46, 11 January 2025 edit undo2601:204:cf01:8ef0:a162:a6b7:7b6e:be27 (talk)No edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|none}} | |||

| {{Gun politics by country}} | |||

| {{for|the context of these debates|Gun violence in the United States}} | |||

| {{redirect|Gun Reform|current gun laws in the U.S.|Gun law in the United States}} | |||

| {{use mdy dates|date=January 2024}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{USgunlegalbox}} | {{USgunlegalbox}} | ||

| '''Gun politics in the United States''' is characterized by two primary opposing ideologies regarding private ]. | |||

| '''Gun politics''' is a ] issue in ].<ref name="Wilcox">{{cite book |author=Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. |title=The changing politics of gun control |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |location=Lanham, Md |year=1998 |pages=1–4 |isbn=0-8476-8614-0}}</ref> For the last several decades, the debate regarding both the restriction and availability of firearms within the ] has been characterized by a stalemate between a ] found in the ] to the ] and the responsibility of government to prevent ].<ref name="Wilcox4">{{cite book |author=Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. |title=The changing politics of gun control |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |location=Lanham, Md |year=1998 |page=4 |isbn=0-8476-8615-9 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=VvNb5s8Z3b0C&pg=PA4 |quote= For many years a feature of this policy arena has been an insurmountable deadlock between a well-organized outspoken minority and a seemingly ambivalent majority}}</ref><ref name = "SpitzerCh1"/> | |||

| Advocates of ] support increasingly restrictive regulations on gun ownership, while proponents of ] oppose such restrictions and often support the liberalization of gun ownership. These groups typically differ in their interpretations of the ], as well as in their views on the role of firearms in public safety, their impact on public health, and their relationship to crime rates at both national and state levels.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ingraham |first=Christopher |date=2021-11-24 |title=Analysis {{!}} It's time to bring back the assault weapons ban, gun violence experts say |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/02/15/its-time-to-bring-back-the-assault-weapons-ban-gun-violence-experts-say/ |access-date=2023-08-07 |newspaper=Washington Post |language=en-US |issn=0190-8286 |archive-date=February 18, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180218051056/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/02/15/its-time-to-bring-back-the-assault-weapons-ban-gun-violence-experts-say/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Withers |first=Rachel |date=2018-02-16 |title=Jimmy Kimmel Cried Again While Addressing the Parkland Shooting, Desperately Pleading for "Common Sense" |url=https://slate.com/culture/2018/02/jimmy-kimmel-pleads-for-commonsense-gun-reform-through-tears.html |access-date=2023-08-07 |work=Slate |language=en-US |issn=1091-2339 |archive-date=August 14, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210814162217/https://slate.com/culture/2018/02/jimmy-kimmel-pleads-for-commonsense-gun-reform-through-tears.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Bruce-Wilcox1998Ch1">{{cite book |last1=Bruce |first1=John M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VvNb5s8Z3b0C |title=The Changing Politics of Gun Control |last2=Wilcox |first2=Clyde |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=1998 |isbn=978-0847686155 |editor1-last=Bruce |editor1-first=John M. |location=Lanham, Maryland |chapter=Introduction |oclc=833118449 |editor2-last=Wilcox |editor2-first=Clyde |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VvNb5s8Z3b0C&pg=PA1}}</ref>{{rp|1–3}}<ref name="PGC1995Ch1">{{cite book |last=Spitzer |first=Robert J. |url=https://archive.org/details/politicsofguncon00spit |title=The Politics of Gun Control |publisher=Chatham House |year=1995 |isbn=978-1566430227}}</ref> | |||

| ==Gun culture== | |||

| {{Main|Gun culture}} | |||

| In his article, "America as a Gun Culture," historian ] popularized the phrase "]" to describe the long-held affections for firearms within U.S., many citizens embracing and celebrating the association of guns and America's heritage.<ref>Hofstadter, Richard. "." ''American Heritage Magazine'', October 1970.</ref> The right to own a gun and defend oneself is considered by some, especially those in the ] and ],<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/health/interactives/guns/ownership.html | work=The Washington Post | title=Gun Ownership by State}}</ref> as a central tenet of the ]. This stems in part from the nation's frontier history, where guns were integral to ], enabling settlers to guard themselves from ]s, animals and foreign armies, frontier citizens often assuming responsibility for self-protection. The importance of guns also derives from the role of hunting in ], which remains popular as a sport in the country today.<ref name="abcgunculture">{{Cite web |url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/indepth/featureitems/s1899524.htm |title=A look inside America's gun culture |work=ABC News Online |date= 2007-04-17 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080602013337/http://www.abc.net.au/news/indepth/featureitems/s1899524.htm |archivedate=Jun 02, 2008 |postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}</ref> | |||

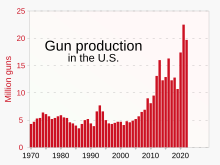

| Since the early 21st century, private firearm ownership in the United States has been steadily increasing, with a notable acceleration during and after 2020.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Helmore |first=Edward |date=2021-12-20 |title=Gun purchases accelerated in the US from 2020 to 2021, study reveals |url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/dec/20/us-gun-purchases-2020-2021-study |access-date=2024-01-25 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> | |||

| The viewpoint that firearms were an integral part of the settling of the United States has the lowest level of support in urban and industrialized regions,<ref name="abcgunculture" /> where a cultural tradition of conflating violence and associating gun ownership with the "]" stereotype has played a part in promoting the support of gun regulation.<ref>William B. Bankston, Carol Y. Thompson, Quentin A. L. Jenkins, Craig J. Forsyth (1990) The Influence of Fear of Crime, Gender, and Southern Culture on Carrying Firearms for Protection. The Sociological Quarterly 31 (2) , 287–305</ref> | |||

| According to the National Firearms Survey of 2021, the largest and most comprehensive study of U.S. firearm ownership, privately owned firearms are involved in approximately 1.7 million defensive use cases annually.<ref>{{Cite web |last=English |first=William |date=May 18, 2022 |title=2021 National Firearms Survey: Updated Analysis Including Types of Firearms Owned |doi=10.2139/ssrn.4109494 |ssrn=4109494 |s2cid=249165467 |url=https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4109494 |access-date=January 25, 2024 |archive-date=January 25, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240125095400/https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4109494 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1995, the ] estimated that the number of firearms available in the US was 223 million.<ref> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/guic.pdf | |||

| |title=Bureau of Justice Statistics Selected Findings | |||

| |accessdate=2008-01-21 | |||

| |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20071214215005/http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/guic.pdf <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 2007-12-14}}</ref> In 2005, almost 18% of U.S. households possessed handguns, compared to almost 3% of households in Canada that possessed handguns.<ref name=icvs>, by the ]. See Table 18 on page 279.</ref> In 2011, the number was increased to 34% of adults in the United States who personally owned a gun; 46% of adult men, and 23% of adult women. In 2011, 47% of the adult U.S. population lived in households with guns.<ref name=gallupguns>. By Lydia Saad. October 26, 2011. ]</ref><ref name="justfacts">{{cite web|url=http://www.justfacts.com/gun_control.htm |title="Gun Control", Just the Facts, 2005-12-30 (revised) |publisher=Justfacts.com |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| Guns are prominent in contemporary U.S. popular culture as well, appearing frequently in movies, television, music, books, and magazines.<ref> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/16/AR2007021600161.html?nav=rss_technology | |||

| |title=Report Urges FCC to Regulate TV Violence | |||

| |publisher=The Washington Post | |||

| |date=2007-02-16 | |||

| |accessdate=2008-01-27 | |||

| | first=John | |||

| | last=Dunbar | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| The survey also indicates a rise in the diversity of firearm owners, with increased ownership rates among females and ethnic minorities compared to previous years.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Sullum |first=Jacob |date=2022-09-09 |title=The largest-ever survey of American gun owners finds that defensive use of firearms is common |url=https://reason.com/2022/09/09/the-largest-ever-survey-of-american-gun-owners-finds-that-defensive-use-of-firearms-is-common/ |access-date=2024-01-25 |website=Reason.com |language=en-US |archive-date=November 21, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231121173323/https://reason.com/2022/09/09/the-largest-ever-survey-of-american-gun-owners-finds-that-defensive-use-of-firearms-is-common/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-09-08 |title=Largest-Ever Survey of Gun Owners Finds Diversity Increasing, Carrying Common, and More Than 1.6 Million Defensive Uses Per Year |url=https://thereload.com/largest-ever-survey-of-gun-owners-finds-diversity-increasing-carrying-common-and-more-than-1-6-million-defensive-uses-per-year/ |access-date=2024-01-25 |website=The Reload |language=en-US |archive-date=January 25, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240125095401/https://thereload.com/largest-ever-survey-of-gun-owners-finds-diversity-increasing-carrying-common-and-more-than-1-6-million-defensive-uses-per-year/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| The origins of American controversy over ownership and carrying of ] can be traced back to the ], hunting/sporting ] and the militia/frontier ethos that draw from the country's early history,<ref name="SpitzerCh1">Spitzer, Robert J.: ''The Politics of Gun Control'', Chapter 1. Chatham House Publishers, 1995.</ref> | |||

| and even further to the rights of ] under the ] ] and long-standing rights of the citizens of a republic as described as far back as ] and ].<ref name=halbrook1984>{{cite book|last=Halbrook|first=Stephen P.|title=That Every Man Be Armed: the evolution of a Constitutional Right|year=1984|publisher=University of New Mexico Press|isbn=0-945999-28-3}}</ref> | |||

| U.S. gun politics is increasingly influenced by demographic factors and ], with notable differences observed in gender, age, and income levels as reported by major social surveys.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lizotte |first1=Mary-Kate |date=July 3, 2019 |title=Authoritarian Personality and Gender Differences in Gun Control Attitudes |journal=Journal of Women, Politics & Policy |volume=40 |issue=3 |pages=385–408 |doi=10.1080/1554477X.2019.1586045 |s2cid=150628197}}</ref><ref name="PGC2012Ch1">{{cite book |last=Spitzer |first=Robert J. |title=The Politics of Gun Control |publisher=Paradigm |year=2012 |isbn=978-1594519871 |location=Boulder, Colorado |chapter=Policy Definition and Gun Control |oclc=714715262 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NSOquAAACAAJ}}</ref> | |||

| Plato, speaking as ] in '']'', "provided a comprehensive analysis of the social and political consequences of individual ownership of arms versus a ] of arms... individual possession of weapons by sane individuals was ethically acceptable to Socrates."<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 9 --> | |||

| Aristotle's concept of ] included a large middle class in which each citizen fulfillied all three functions of self-legislation, arms bearing, and working."<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 11 --> | |||

| Aristotle criticized the monopolization of arms bearing by a single class in the "Best State" writings of ], arguing it would lead to oppression of the "farmers" and the "workers" by the arms-bearing class.<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 11-12 --> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Early ] required that subjects be armed for the defense of the realm. Later kings, especially those best known "for arbitrary absolutism sought to deprive the lower economic classes, various religious groups, and colonized peoples of weapons so as to perpetuate and enhance the economic and political power of the dominant classes."<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 37 --> | |||

| ], notable pioneer frontierswoman and scout, aged 43]] | |||

| Common law construction came to establish the right of freeman to be armed, both before and after the ] of 1688, and were further enshrined in the ], and through long-standing ]. Despite ]ary legislation that routinely attempted to disarm the ] and ] throughout the eighteenth century, many Americans believed they were guaranteed the common-law right to keep and carry arms.<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 37-54 --> | |||

| Firearms in American life begin with the earliest attempts to settle and colonize the United States. Firearms were made, imported and provided for agrarian, hunting, defense and diplomatic purposes. A connection between shooting skills and survival among American men in the colonial expanses was often a necessity, and could serve as a ']' for those entering manhood.<ref name=PGC2012Ch1/>{{rp|9}} Today, the figures of the settler colonist, hunter and outdoorsman survive as central to American gun culture, regardless of modern trends away from hunting and rural life.<ref name=PGC1995Ch1/> | |||

| Prior to the ], there was neither the ability nor political desire to maintain a standing army in the American colonies. Since at least the time of the ], English political ideology was strongly opposed to the idea of a ]. Therefore, the armed citizen-soldier carried responsibility. Service in colonial militia, including providing one's own ammunition and weapons, was mandatory for all men. Yet, as early as the 1790s, the mandatory universal militia duty evolved gradually to voluntary militia units and a reliance on a ]. Throughout the 19th century the institution of the organized civilian militia gradually declined.<ref name=PGC2012Ch1/>{{rp|10}} The unorganized civilian militia under current U.S. law consists of all able-bodied males at least seventeen years of age and under the age of 45—with some exceptions—who are not members of the National Guard or Naval Militia, as codified in {{UnitedStatesCode|10|246}}. | |||

| Americans who participated in the ] were strongly influenced by the philosophical classics from ] to ] to ] writers, and were vigorous in asserting the importance of their ''common-law'' rights to both keep and bear arms for individual self-defense, and "to combine into independent ]s for defense against the official ] ] and militias."<ref name=halbrook1984/><!-- Halbrook, 1984, p. 55 --> | |||

| Closely related to the militia tradition is the frontier tradition, with the need for self-protection pursuant to westward expansion and the extension of the ].<ref name=PGC2012Ch1/>{{rp|10–11}} Though it has not been a necessary part of daily survival for over a century, "generations of Americans continued to embrace and glorify it as a living inheritance{{snd}}as a permanent ingredient of this nation's style and culture".<ref name=Anderson1984>{{cite book |last=Anderson |first=Jervis |year=1984 |title=Guns in American Life |url=https://archive.org/details/gunsinamericanli00ande |url-access=registration |quote=ingredient. |publisher=Random House |isbn=978-0394535982}}</ref>{{rp|21}} | |||

| ], notable pioneer frontierswoman and scout, at age 43. Photo by ].]] | |||

| Since the founding-era of American Federalist politics, debates regarding firearm availability and gun violence in the United States have been characterized by concerns about the ], as found in the ], and the responsibility of the ] to serve the needs of its citizens and to prevent ]. Firearms regulation supporters say that indiscriminate or unrestricted gun rights inhibit the government from fulfilling that responsibility, and causes a safety concern. Gun rights supporters promote firearms for ] – including ], as well as ] and ].<ref name="Levan">{{cite book |last=Levan |first=Kristine |year=2013 |chapter=4 Guns and Crime: Crime Facilitation Versus Crime Prevention |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h4aWFrgW74YC&pg=PA93|editor1-last=Mackey |editor1-first=David A. |editor2-last=Levan |editor2-first=Kristine |title=Crime Prevention |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h4aWFrgW74YC|publisher=Jones & Bartlett |page=438 |isbn=978-1449615932|quote= They promote the use of firearms for self-defense, hunting, and sporting activities, and also promote firearm safety.}}</ref>{{rp|96}}<ref name="Larry Pratt">{{cite web |url=http://gunowners.org/fs9402.htm |title=Firearms: the People's Liberty Teeth |author=Larry Pratt |access-date=December 30, 2008}}</ref> Gun control advocates state that restricting and tracking gun access would result in safer communities, while gun rights advocates state that increased firearm ownership by law-abiding citizens reduces crime and assert that criminals have always had easy access to firearms.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/11/us/how-criminals-get-guns-in-short-all-too-easily.html|title=How Criminals Get Guns: In Short, All Too Easily|last=Terry|first=Don|date=1992-03-11|work=The New York Times|access-date=2017-12-08|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=August 1, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220801135007/https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/11/us/how-criminals-get-guns-in-short-all-too-easily.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>]. ''More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Laws'' (University of Chicago Press, 3rd ed., 2010) {{ISBN|978-0226493664}}</ref> | |||

| The American hunting/sporting passion comes from a time when the United States was an agrarian, subsistence nation where hunting was a profession for some, an auxiliary source of food for some settlers, and also a deterrence to animal predators. A connection between shooting skills and survival among rural American men was in many cases a necessity and a ']' for those entering manhood. Today, hunting survives as a central sentimental component of a gun culture as a way to control animal populations across the country, regardless of modern trends away from subsistence hunting and rural living.<ref name = "SpitzerCh1"/> | |||

| Gun legislation in the United States has become increasingly subject to federal judicial interpretation of the Constitution. The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/second_amendment|title=Second Amendment|last=Strasser|first=Mr. Ryan|date=2008-07-01|website=LII / Legal Information Institute|language=en|access-date=2018-10-27|archive-date=September 11, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170911162147/https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/second_amendment|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1791, the United States adopted the Second Amendment, and in 1868 adopted the ]. The historical tradition bounded by these two amendments has been the subject of ] decisions in '']'' (2008), where the Court affirmed for the first time that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to possess firearms for traditionally lawful purposes (such as self-defense within the home), independent of service in a state militia, in '']'' (2010), where the Court ruled that the Second Amendment's restrictions are ] by the ] of the Fourteenth Amendment and thereby apply to state as well as federal law, and most recently in the '']'' (2022). As emphasized in ''Bruen'', the Second Amendment makes an "unqualified command" that the "individual-right" of firearms ownership, as opposed to the collective or militia-based theory of the right, is protected from all restriction unless a government authority can demonstrate their law is with the Nation's historical tradition of firearms regulation.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Williams |first1=Pete |title=Supreme Court allows the carrying of firearms in public in major victory for gun rights groups |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/supreme-court/supreme-court-says-second-amendment-guarantees-right-carry-guns-public-rcna17721 |access-date=June 26, 2022 |publisher=NBC News |date=June 23, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220626001859/https://www.businessinsider.com/supreme-court-guns-decision-second-amendment-new-york-2022-6 |archive-date=June 26, 2022}}</ref> | |||

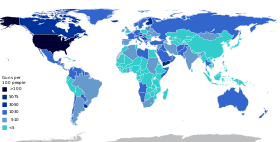

| In 2018 it was estimated that ],<ref> Estimating Global CivilianHELD Firearms Numbers. Aaron Karp. June 2018</ref> and that 40% to 42% of the households in the country have at least one gun. However, record gun sales followed in the following years.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Schaeffer |first1=Kathleen |title=Key facts about Americans and guns |url=https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/13/key-facts-about-americans-and-guns/ |website=Pew Research Center |publisher= |access-date=October 14, 2022 |archive-date=October 13, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221013212701/https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/13/key-facts-about-americans-and-guns/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author1=Desilver, Drew|title=A Minority of Americans Own Guns, But Just How Many Is Unclear|url=http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/04/a-minority-of-americans-own-guns-but-just-how-many-is-unclear/|website=Pew Research Center|access-date=October 25, 2015|date=June 4, 2013|archive-date=August 17, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220817173925/https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/06/04/a-minority-of-americans-own-guns-but-just-how-many-is-unclear/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170915200955/http://www.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx |date=September 15, 2017 }}, Gallup. Retrieved October 25, 2015.</ref> The U.S. has by far the highest estimated number of guns per capita in the world, at 120.5 guns for every 100 people.<ref name=SmallArmsSurvey2017>. June 2018 by Aaron Karp. Of ]. See box 4 on page 8 for a detailed explanation of "Computation methods for civilian firearms holdings". See country table in annex PDF: . See {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191117202015/http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/weapons-and-markets/tools/global-firearms-holdings.html |date=November 17, 2019 }}.</ref> | |||

| The militia/frontiersman spirit derives from an early American dependence on arms to protect themselves from foreign armies and hostile Native Americans. Survival depended upon everyone being capable of using a weapon. Prior to the ] there was neither budget nor manpower nor government desire to maintain a full-time army. Therefore, the armed citizen-soldier carried the responsibility. Service in militia, including providing one's own ammunition and weapons, was mandatory for all men—just as registering for military service upon turning eighteen is today. Yet, as early as the 1790s, the mandatory universal militia duty gave way to voluntary militia units and a reliance on a ]. Throughout the 19th century the institution of the civilian militia began to decline.<ref name = "SpitzerCh1"/> | |||

| ===Colonial era through the Civil War=== | |||

| Closely related to the militia tradition was the frontier tradition with the need for a means of self-protection closely associated with the nineteenth century westward expansion and the ]. There remains a powerful central elevation of the gun associated with the hunting/sporting and militia/frontier ethos among the American Gun Culture.<ref name="SpitzerCh1" /> Though it has not been a necessary part of daily survival for over a century, generations of Americans have continued to embrace and glorify it as a living inheritance—a permanent element of the nation's style and culture.<ref>JERVIS ANDERSON, GUNS IN AMERICA 10 (1984), page 21</ref> | |||

| In the summer of 1619 in ], leaders of the settlement came together to pass the first gun law:<ref>{{Cite web |last=Spitzer |first=Robert J. |date=2023-08-12 |title=America's Original Gun Control |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/08/america-history-gun-control-supreme-court/674985/ |access-date=2023-08-13 |website=The Atlantic |language=en |archive-date=August 13, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230813044317/https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/08/america-history-gun-control-supreme-court/674985/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=That no man do sell or give any Indians any piece, shot, or powder, or any other arms offensive or defensive, upon pain of being held a traitor to the colony and of being hanged as soon as the fact is proved, without all redemption.}} | |||

| ], by ] stands at the town green of ].)]] | |||

| In the years prior to the ], the British, in response to the colonists' unhappiness over increasingly direct control and taxation of the colonies, imposed a gunpowder embargo on the colonies in an attempt to lessen the ability of the colonists to resist British encroachments into what the colonies regarded as local matters. Two direct attempts to disarm the colonial militias fanned what had been a smoldering resentment of British interference into the fires of war.<ref name="Revwar75.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.revwar75.com/battles/primarydocs/williamsburg.htm |title=Primary Documents Relating to the Seizure of Powder at Williamsburg, VA, April 21, 1775 |last1=Reynolds |first1=Bart |date=September 6, 2006 |website=revwar75.com |location=Horseshoe Bay, Texas |publisher=John Robertson |type=transcription, amateur? |access-date=November 21, 2010 |archive-date=August 18, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210818064945/http://www.revwar75.com/battles/primarydocs/williamsburg.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| These two incidents were the attempt to confiscate the cannon of the Concord and Lexington militias, leading to the ] of April 19, 1775, and the attempt, on April 20, to confiscate militia powder stores in the armory of Williamsburg, Virginia, which led to the ] and a face-off between ] and hundreds of militia members on one side and the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, and British seamen on the other. The Gunpowder Incident was eventually settled by paying the colonists for the powder.<ref name="Revwar75.com"/> | |||

| ===Popular culture=== | |||

| The gun has long been a symbol of power and masculinity.<ref name="isbn0-275-98256-4">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Sidel, Victor W.; Wendy Cukier |title=The Global Gun Epidemic: From Saturday Night Specials to AK-47s |publisher=Praeger Security International General Interest-Cloth |year=2005 |page=130 | |||

| |isbn=0-275-98256-4}}</ref> In popular literature, frontier adventure was most famously told by ], who is credited by Petri Liukkonen with creating the archetype of an 18th-century frontiersman through such novels as "]" (1826) and "]" (1840).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/jfcooper.htm |title=James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) |publisher=Kirjasto.sci.fi |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| According to historian ], states passed some of the first gun control laws, beginning with Kentucky's law to "curb the practice of carrying concealed weapons in 1813." There was opposition and, as a result, the ] interpretation of the Second Amendment began and grew in direct response to these early gun control laws, in keeping with this new "pervasive spirit of individualism." As noted by Cornell, "Ironically, the first gun control movement helped give birth to the first self-conscious gun rights ideology built around a constitutional right of individual self-defense."<ref name=Cornell2006>{{cite book |last=Cornell |first=Saul |year=2006 |title=A Well-Regulated Militia: The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America |url=https://archive.org/details/wellregulatedmil00corn_0 |url-access=registration |location=New York |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0195147865 |oclc=62741396}}</ref>{{rp|140–141}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment first arose in '']'' (1822),<ref name="bliss v commonwealth">{{cite court |litigants=Bliss v. Commonwealth |vol=2 |reporter=Littell |opinion=90 |date=KY 1822 |url=https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/wbardwel/public/nfalist/bliss_v_commonwealth.txt |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081211212146/https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/wbardwel/public/nfalist/bliss_v_commonwealth.txt |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref> which evaluated the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of ] (1799). The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about "a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons was violative of the Second Amendment".<ref name = "1967hearing"> | |||

| In the late 19th century, cowboy and ] imagery entered the collective imagination. The first American female superstar, ], was a ] who toured the country starting in 1885, performing in ]'s Wild West show. The cowboy archetype of individualist hero was established largely by ] in stories and novels, most notably ''The Virginian'' (1902), following close on the heels of ]'s ''The Winning of the West'' (1889–1895), a history of the early frontier.<ref>{{Cite web |title=American Literature: Prose, MSN Encarta |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761564847_8/American_Literature_Prose.html |work= |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kwqNkxgD |archivedate=2009-10-31 |postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/i_r/roosevelt.htm |title=New Perspectives on the West: Theodore Roosevelt, PBS, 2001 |publisher=Pbs.org |date=1919-01-06 |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/owister.htm |title="Owen Wister (1860-1938)", Petri Liukkonen, Authors' Calendar, 2002 |publisher=Kirjasto.sci.fi |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> Cowboys were also popularized in turn of the 20th century cinema, notably through such early classics as '']'' (1903) and ''A California Hold Up'' (1906) -- the most commercially successful film of the pre-nickelodeon era.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html |title="Western Films", Tim Dirks, Filmsite, 1996-2007 |publisher=Filmsite.org |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| The United States. Anti-Crime Program. Hearings Before Ninetieth Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967, p. 246.</ref> | |||

| Gangster films began appearing as early as 1910, but became popular only with the advent of sound in film in the 1930s. The genre was boosted by the events of the ] era, such as bootlegging and the ] of 1929, the existence of real-life gangsters (e.g., ]) and the rise of contemporary ] and escalation of urban violence. These movies flaunted the archetypal exploits of "swaggering, cruel, wily, tough, and law-defying bootleggers and urban gangsters."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.filmsite.org/crimefilms.html |title="Crime and Gangster Films", Tim Dirks, Filmsite, 1996-2007 |publisher=Filmsite.org |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| The first state court decision relevant to the "right to bear arms" issue was ''Bliss v. Commonwealth''. The Kentucky court held that "the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire,..."<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pierce |first=Darell R. |year=1982 |title=Second Amendment Survey |url=https://chaselaw.nku.edu/content/dam/chaselaw/docs/academics/lawreview/v10/nklr_v10n1.pdf |journal=Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980s |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=155–162 |access-date=2014-04-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170820035837/https://chaselaw.nku.edu/content/dam/chaselaw/docs/academics/lawreview/v10/nklr_v10n1.pdf |archive-date=2017-08-20 |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{rp|161}}<ref>Two states, ] and ], do not require a permit or license for carrying a concealed weapon to this day, following Kentucky's original position.</ref> | |||

| With the arrival of ], Hollywood produced many morale boosting movies, patriotic rallying cries that affirmed a sense of national purpose. The image of the lone cowboy was replaced in these combat films by stories that emphasized group efforts and the value of individual sacrifices for a larger cause, often featuring a group of men from diverse ethnic backgrounds who were thrown together, tested on the battlefield, and molded into a dedicated fighting unit.<ref>{{cite web|author=Digital History, Steven Mintz |url=http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/historyonline/hollywood_history.cfm#wartime |title=Hollywood as History: Wartime Hollywood, Digital History |publisher=Digitalhistory.uh.edu |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| Also during the Jacksonian Era, the first ] (or group right) interpretation of the Second Amendment arose. In '']'' (1842), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, "that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense",<ref name="state v buzzard">{{cite court |litigants=State v. Buzzard |vol=4 |reporter=Ark. (2 Pike) |opinion=18 |year=1842 |url=http://www.constitution.org/2ll/2ndcourt/state/191st.htm |trans-title=Archived copy |access-date=April 30, 2008 |archive-date=June 5, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080605142712/http://www.constitution.org/2ll/2ndcourt/state/191st.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons. | |||

| Guns frequently accompanied famous heroes and villains in late 20th-century American films, from the outlaws of '']'' (1967) and '']'' (1972), to the fictitious law and order avengers like '']'' (1971) and '']'' (1987). In the 1970s, films portrayed fictitious and exaggerated characters, madmen ostensibly produced by the ] in films like '']'' (1976) and '']'' (1979), while other films told stories of fictitious veterans who were supposedly victims of the war and in need of rehabilitation ('']'' and '']'', both 1978).<ref>{{cite web|author=Digital History, Steven Mintz |url=http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/historyonline/hollywood_history.cfm#new |title=Hollywood as History: The "New" Hollywood, Digital History |publisher=Digitalhistory.uh.edu |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> Many action films continue to celebrate the gun toting hero in fantastical settings. At the same time, the negative role of the gun in fictionalized modern urban violence has been explored in films like '']'' (1991) and '']'' (1993). | |||

| The Arkansas high court declared "That the words 'a well-regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State', and the words 'common defense' clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms." ]'s influential ''Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes'' (1873) took Buzzard's militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the "Arkansas doctrine," as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.<ref name="state v buzzard"/><ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Bishop">{{cite book |author=Cornell, Saul |title=A Well-Regulated Militia – The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New York |year=2006 |pages= |isbn=978-0195147865 |quote="Dillon endorsed Bishop's view that ''Buzzard's'' "Arkansas doctrine," not the libertarian views exhibited in ''Bliss, captured the dominant strain of American legal thinking on this question'' |url=https://archive.org/details/wellregulatedmil00corn_0/page/188 }}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The two early state court cases, ''Bliss'' and ''Buzzard'', set the fundamental dichotomy in interpreting the Second Amendment, i.e., whether it secured an individual right versus a collective right.{{citation needed|reason=Many state cases with opposing views, why are we calling out these two?|date=April 2014}} | |||

| ===Revolutionary War=== | |||

| ===Post Civil War=== | |||

| ] ] Statue is by ] and it stands at the town green of ].)]]In the years prior to the Revolutionary War, the British, in response to the colonists' unhappiness over increasingly direct control and taxation of the colonies, imposed a powder embargo on the colonies in an attempt to lessen the ability of the colonists to resist British encroachments into what the colonies regarded as local matters. Two direct attempts to disarm the colonial militias fanned what had been a smoldering resentment of British interference into the fires of war.<ref name="Revwar75.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.revwar75.com/battles/primarydocs/williamsburg.htm |title=The Seizure Williamsburg, Va. Powder Magazine - April 21, 1775 |publisher=Revwar75.com |date= |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Reconstruction era}} | |||

| <!-- Need mention of the melting-point laws (pg394 {{ISBN|0814718795}}) --> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] published in '']'' magazine shortly after the ]]] | |||

| In the years immediately following the ], the question of the rights of freed slaves to carry arms and to belong to the militia came to the attention of the federal courts. In response to the problems freed slaves faced in the Southern states, the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted. | |||

| When the ] was drafted, Representative ] of ] used the Court's own phrase "privileges and immunities of citizens" to include the first Eight Amendments of the Bill of Rights under its protection and guard these rights against state legislation.<ref name="Kerrigan">{{cite web |author=Kerrigan, Robert |title=The Second Amendment and related Fourteenth Amendment |date=June 2006 |format=PDF |url=http://secondamendment.and.fourteenth.googlepages.com/ |access-date=2008-05-06 |archive-date=2009-01-24 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090124170044/http://secondamendment.and.fourteenth.googlepages.com/ |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| These two incidents were the attempt to confiscate the cannon of the Concord and Lexington militias, leading to the ] of April 19, 1775, and the attempt, on April 20, to confiscate militia powder stores in the armory of Williamsburg, Virginia, which led to the ] and a face off between ] and hundreds of militia members on one side and the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, and British seamen on the other. The Gunpowder Incident was eventually settled by paying the colonists for the powder.<ref name="Revwar75.com"/> | |||

| The debate in Congress on the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War also concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves. One particular concern was the disarming of former slaves. | |||

| Minutemen were members of teams of select men from the American ] during the ] who vowed to be ready for battle against the British within one minute of receiving notice{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}}. On the night of April 18/April 19, 1775, minuteman ], William Dawes, and Dr. ] spread the news that "the Regulars are coming out!"<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |last1= Revere | |||

| |first1= Paul | |||

| |others= Introduction by Edmund Morgan | |||

| |year= 1961 | |||

| |title= Paul Revere's Three Accounts of His Famous Ride | |||

| |location= Boston | |||

| |publisher= Massachusetts Historical Society | |||

| |isbn=978-0-9619999-0-2 | |||

| }}</ref> Paul Revere was captured before completing his mission when the British marched towards the armory in ] to seize the Massachusetts militia's gunpowder magazine which had been hidden there. Only Dr. Prescott was able to complete the journey to Concord.<ref>Wills, Garry (1999). ''A Necessary Evil: A History of American Distrust of Government'', Page 33. New York, NY; Simon & Schuster</ref> The right to a militia was thus an issue in the United States from the very beginning. | |||

| The Second Amendment attracted serious judicial attention with the Reconstruction era case of '']'' which ruled that the ] of the Fourteenth Amendment did not cause the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, to limit the powers of the State governments, stating that the Second Amendment "has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government." | |||

| ===Jacksonian era=== | |||

| States passed some of the first gun control laws. There was opposition and, as a result, the Individual Right interpretation of the Second Amendment began and grew in direct response to these early gun control laws, in keeping with this new "pervasive spirit of individualism."<ref name="Saul_Cornell_Individual"/> As noted by Cornell, "Ironically, the first gun control movement helped give birth to the first self-conscious gun rights ideology built around a constitutional right of individual self-defense."<ref name="Saul_Cornell_Individual">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| |title=A Well-Regulated Militia{{spaced ndash}}The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=140–141 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Akhil Reed Amar notes in '']'', the basis of common law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which would include the Second Amendment, "following ]'s famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist ] case, ''] v. Illinois''": | |||

| The Individual Right interpretation of the Second Amendment first arose in ''Bliss v. Commonwealth'' (1822, KY),<ref name="bliss v commonwealth">{{cite court |litigants=Bliss v. Commonwealth |vol=2 |reporter=Littell |opinion=90 |date=KY 1822 |url=http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/wbardwel/public/nfalist/bliss_v_commonwealth.txt | |||

| |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20081211212146/http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/wbardwel/public/nfalist/bliss_v_commonwealth.txt | |||

| |archivedate=2--8-12-12 | |||

| }}</ref> which evaluated the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of ] (1799). The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about "a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons was violative of the Second Amendment".<ref name = "1967hearing">United States. Anti-Crime Program. Hearings Before Ninetieth Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1967, p. 246.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet in so far as they secure and recognize fundamental rights{{snd}}common law rights{{snd}}of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States...<ref>{{cite journal |last=Amar |first=Akhil Reed |year=1992 |title=The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment |url=http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/1040/ |journal=Yale Law Journal |volume=101 |issue=6 |pages=1193–1284 |doi=10.2307/796923 |jstor=796923 |archive-date=April 7, 2014 |access-date=April 2, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407060600/http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/1040/ |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|1270}}}} | |||

| The first relevant state court decision was ''Bliss v. Commonwealth''. The Kentucky court held that "the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire.... This holding was unique because it stated that the right to bear arms is absolute and unqualified."<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pierce |first=Darell R. |title=Second Amendment Survey |journal=Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980's |volume=10 |issue=1 |year=1982 |page=155}}</ref><ref>Two states, ] and ], do not require a permit or license for carrying a concealed weapon to this day, following Kentucky's original position.</ref> | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| Also during the Jacksonian Era, the first Collective Right interpretation of the Second Amendment arose. In ''State v. Buzzard'' (1842, Ark), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, "that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense",<ref name="state v buzzard">{{cite court |litigants=State v. Buzzard |vol=4 |reporter=Ark. (2 Pike) |opinion=18 |year=1842 |url=http://www.constitution.org/2ll/2ndcourt/state/191st.htm}}</ref> while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons. | |||

| ====First half of 20th century==== | |||

| Since the late 19th century, with three key cases from the ], the U.S. Supreme Court consistently ruled that the Second Amendment (and the Bill of Rights) restricted only Congress, and not the States, in the regulation of guns.<ref>See ] 92 U.S. 542 (1876), ] 116 U.S. 252 (1886), Miller v. Texas 153 U.S. 535 (1894)</ref> Scholars predicted that the Court's incorporation of other rights suggested that they may incorporate the Second, should a suitable case come before them.<ref name=autogenerated2>Levinson, Sanford: ''The Embarrassing Second Amendment'', 99 Yale L.J. 637–659 (1989)</ref> | |||

| =====National Firearms Act===== | |||

| The Arkansas high court declared "That the words 'a well regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State', and the words 'common defense' clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms." ]'s influential ''Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes'' (1873) took Buzzard's militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the "Arkansas doctrine", as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.<ref name="state v buzzard"/><ref name="Saul_Cornell_AWRM_Bishop">{{cite book | |||

| {{Main|National Firearms Act}} | |||

| |author=Cornell, Saul | |||

| The first major federal firearms law passed in the 20th century was the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. It was passed after ]-era gangsterism peaked with the ] of 1929. The era was famous for criminal use of firearms such as the ] (Tommy gun) and ]. Under the NFA, machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, and other weapons fall under the regulation and jurisdiction of the ] (ATF) as described by ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Boston T. Party (Kenneth W. Royce) |title=Boston on Guns & Courage |publisher=Javelin Press |year=1998 |pages=3:15}}</ref> | |||

| |title=A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA{{spaced ndash}}The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=New York, New York | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |pages=188 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-19-514786-5 | |||

| |quote="Dillon endorsed Bishop's view that ''Buzzard's'' "Arkansas doctrine," not the libertarian views exhibited in ''Bliss, captured the dominant strain of American legal thinking on this question." | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| =====''United States v. Miller''===== | |||

| The two early state court cases, ''Bliss'' and ''Buzzard'', set the fundamental dichotomy in interpreting the Second Amendment, i.e., whether it secured an Individual Right versus a Collective Right. A debate about how to interpret the Second Amendment evolved through the decades and remained unresolved until the 2008 '']'' U.S. Supreme Court decision. | |||

| {{Main|United States v. Miller}} | |||

| In ''United States v. Miller''<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0307_0174_ZO.html |title=United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939) |publisher=Law.cornell.edu |access-date=November 21, 2010 |archive-date=September 15, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100915151047/http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0307_0174_ZO.html |url-status=live }}</ref> (1939) the Court did not address incorporation, but whether a sawn-off shotgun "has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia."<ref name=autogenerated2 /> In overturning the indictment against Miller, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas stated that the National Firearms Act of 1934, "offend the inhibition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution." The federal government then appealed directly to the Supreme Court. On appeal the federal government did not object to Miller's release since he had died by then, seeking only to have the trial judge's ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal law overturned. Under these circumstances, neither Miller nor his attorney appeared before the Court to argue the case. The Court only heard argument from the federal prosecutor. In its ruling, the Court overturned the trial court and upheld the NFA.<ref>"", ] and Denning, Brannon P.</ref> | |||

| ====Second half of 20th century==== | |||

| ===Antebellum era=== | |||

| ] signs the Gun Control Act of 1968 into law.]] | |||

| The Dred Scott decision of 1857 was one of the polarizing decisions that led to the civil war. One minor issue was whether blacks had the citizenship right to bear arms. In '']'', {{ussc|60|393|1856}} the Chief Justice ] wrote for the majority: "It would give to persons of the negro race, who were recognized as citizens in any one State of the Union... the full liberty... to keep and carry arms wherever they went." | |||

| The ] (GCA) was passed after the assassinations of President ], Senator ], and African-American activists ] and ] in the 1960s.<ref name=PGC2012Ch1/> The GCA focuses on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by generally prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers, and importers. It also prohibits selling firearms to certain categories of individuals defined as "prohibited persons." | |||

| In 1986, Congress passed the ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140513095318/https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/99/s49 |date=May 13, 2014 }}. GovTrack.us.</ref> It was supported by the National Rifle Association because it reversed many of the provisions of the GCA. It also banned ownership of unregistered fully automatic rifles and civilian purchase or sale of any such firearm made from that date forward.<ref>{{cite news |last=Joshpe |first=Brett |date=January 11, 2013 |title=Ronald Reagan Understood Gun Control |url=https://www.courant.com/2013/01/11/ronald-reagan-understood-gun-control-2/ |newspaper=Hartford Courant |type=op-ed |access-date=May 11, 2014 |archive-date=May 12, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140512222200/http://articles.courant.com/2013-01-11/news/hc-op-joshpe-ronald-reagan-supported-gun-restricti-20130111_1_gun-restrictions-gun-rights-brady-bill |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Welna |first=David |date=January 16, 2013 |title=The Decades-Old Gun Ban That's Still On The Books |url=https://www.npr.org/blogs/itsallpolitics/2013/01/18/169526687/the-decades-old-gun-ban-thats-still-on-the-books |publisher=NPR |access-date=May 11, 2014 |archive-date=May 12, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140512221634/http://www.npr.org/blogs/itsallpolitics/2013/01/18/169526687/the-decades-old-gun-ban-thats-still-on-the-books |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Reconstruction era=== | |||

| {{See also|Reconstruction era}} | |||

| <!-- Need mention of the melting-point laws (pg394 ISBN 0-8147-1879-5) --> | |||

| With the ] ending, the question of the rights of freed slaves to carry arms and to belong to militia came to the attention of the Federal courts. In response to the problems freed slaves faced in the Southern states, the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted. | |||

| The ] in 1981 led to enactment of the ] (Brady Law) in 1993 which established the national background check system to prevent certain restricted individuals from owning, purchasing, or transporting firearms.<ref name="evidence from crime gun tracing">{{cite journal|author=Brian Knight|title=State Gun Policy and Cross-State Externalities: Evidence from Crime Gun Tracing|journal=Providence RI|series=Working Paper Series|date=September 2011|doi=10.3386/w17469|url=https://www.nber.org/papers/w17469|doi-access=free|archive-date=September 28, 2021|access-date=September 28, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210928152228/https://www.nber.org/papers/w17469|url-status=live}}</ref> In an article supporting passage of such a law, retired chief justice ] wrote: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| When the ] was drafted, Representative ] of ] used the Court's own phrase "privileges and immunities of citizens" to include the first Eight Amendments of the Bill of Rights under its protection and guard these rights against state legislation.<ref name="Kerrigan">{{cite journal |author=Kerrigan, Robert |title=The Second Amendment and related Fourteenth Amendment |date=June 2006 |format=PDF |url=http://secondamendment.and.fourteenth.googlepages.com}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>Americans also have a right to defend their homes, and we need not challenge that. Nor does anyone seriously question that the Constitution protects the right of hunters to own and keep sporting guns for hunting game any more than anyone would challenge the right to own and keep fishing rods and other equipment for fishing{{spaced ndash}}or to own automobiles. To 'keep and bear arms' for hunting today is essentially a recreational activity and not an imperative of survival, as it was 200 years ago. ']s' and machine guns are not recreational weapons and surely are as much in need of regulation as motor vehicles.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Burger |first=Warren E. |date=January 14, 1990 |title=The Right To Bear Arms: A distinguished citizen takes a stand on one of the most controversial issues in the nation |journal=Parade Magazine |pages=4–6 }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The debate in the Congress on the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War also concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves. One particular concern was the disarming of former slaves. | |||

| A ] in 1989 led to passage of the ] of 1994 (AWB or AWB 1994), which defined and banned the manufacture and transfer of ]" and ]"<ref name=Johnson130402>{{cite news |last=Johnson |first=Kevin |date=April 2, 2013 |title=Stockton school massacre: A tragically familiar pattern |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/01/stockton-massacre-tragically-familiar-pattern-repeats/2043297/ |newspaper=USA Today |access-date=May 2, 2014 |archive-date=March 6, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140306213134/http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/01/stockton-massacre-tragically-familiar-pattern-repeats/2043297/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Second Amendment attracted serious judicial attention with the ] era case of '']'' which ruled that the ] of the Fourteenth Amendment did not cause the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, to limit the powers of the State governments, stating that the Second Amendment "has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government." | |||

| According to journalist ], concerns about gun control laws along with outrage over two high-profile incidents involving the ATF (] in 1992 and the ] in 1993) mobilized the ] of citizens who feared that the federal government would begin to confiscate firearms.<ref name=Berlet040901>{{cite journal |last=Berlet |first=Chip |date=September 1, 2004 |title=Militias in the Frame |journal=Contemporary Sociologists |volume=33 |issue=5 |pages=514–521 |doi=10.1177/009430610403300506 |s2cid=144973852 |quote=All four books being reviewed discuss how mobilization of the militia movement involved fears of gun control legislation coupled with anger over the deadly government mishandling of confrontations with the Weaver family at Ruby Ridge, Idaho and the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas.}}</ref><ref>More ''militia movement'' sources: | |||

| Akhil Reed Amar notes in the '']'', the basis of Common Law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which would include the Second Amendment, "following ]'s famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist ] case, ''] v. Illinois''":{{Quote|Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet in so far as they secure and recognize fundamental rights—common law rights—of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States...<ref>{{cite journal |last=Amar |first=Akhil Reed |title=The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment |journal=] |page=1193 |date=April 1992 |url=http://www.saf.org/LawReviews/Amar1.html}}</ref>}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Chermak |first=Steven M. |year=2002 |title=Searching for a Demon: The Media Construction of the Militia Movement |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=p1NGyz43INkC|publisher=UPNE|isbn=978-1555535414|oclc=260103406 |quote= describes the primary concerns of militia members and how those concerns contributed to the emergence of the militia movement prior to the Oklahoma City bombing. Two high-profile cases, the Ruby Ridge and Waco incidents, are discussed because they have elicited the anger and concern of the people involved in the movement.}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Crothers |first=Lane |year=2003 |title=Rage on the Right: The American Militia Movement from Ruby Ridge to Homeland Security |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PTR7AAAAQBAJ&q=%22chapter+4+examines%22 |location=Lanham, Maryland |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |page=97 |isbn=978-0742525474 |oclc=50630498 |quote=Chapter 4 examines the actions surrounding, and the political impact of, the standoff at Ruby Ridge.... Arguably, the siege... lit the match that ignited the militia movement.}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Freilich |first=Joshua D. |year=2003 |title=American Militias: State-Level Variations in Militia Activities |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cXZAAAAMAAJ&q=cosmology |publisher=LFB Scholarly |page=18 |isbn=978-1931202534 |oclc=501318483 |quote= appear to have taken on a mythological significance within the cosmology of the movement....}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Gallaher |first=Carolyn |year=2003 |title=On the Fault Line: Race, Class, and the American Patriot Movement |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OqDgd4m529gC&pg=PA17|location=Lanham, Maryland |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |page=17 |isbn=978-0742519749|oclc=845530800 |quote=Patriots, however, saw events as the first step in the government's attempt to disarm the populace and pave the way for imminent takeover by the new world order.}}</ref> | |||

| Though gun control is not strictly a partisan issue, there is generally more support for gun control legislation in the ] than in the ].<ref name="spitzer16">Spitzer, Robert J.: ''The Politics of Gun Control'', p. 16. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995.</ref> The ], whose campaign platforms favor limited government regulation, is outspokenly against gun control.<ref>]: in ''Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law'', Vol. I, p. 512 (Gregg Lee Carter, Ed., ABC-CLIO, 2012).</ref> | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| {{See also|Crime in the United States|Gun control policy of the Clinton Administration}} | |||

| A famous and widely publicized case where fully automatic weapons were used in crime in the United States was during the ] during the winter of 1929; this Prohibition-era gangster sub-machine gun mass murder led directly to the ] of 1934, which was passed over a year after ] had ended. Since 1934, fully automatic weapons fall under the regulation and jurisdiction of the ] (ATF). Other crimes involving fully automatic weapons in the United States have not been as widely publicized.<ref>{{cite book |author=Boston T. Party (Kenneth W. Royce) |title=Boston on Guns & Courage |publisher=Javelin Press |year=1998 |pages=3:15}}</ref> However, the lesser known 1997 ] involved two men carrying semi-automatic rifles that were illegally modified to fire in a fully automatic fashion.<ref>{{cite news |title=Botched L.A. bank heist turns into bloody shootout |url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9702/28/shootout.update/ |publisher=CNN|accessdate=2008-04-08}}</ref> | |||

| <!--need discussion of political aftermath of McKinley assassination.--> | |||

| =====Advocacy groups===== | |||

| ] signs the Gun Control Act of 1968 into law]] | |||

| The ] (NRA) was founded to promote firearm competency and natural conservation in 1871. The NRA supported the NFA and, ultimately, the GCA.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Bennett |first=Cory |date=December 21, 2012 |title=The Evolution of the NRA's Defense of Guns: A Brief History of the NRA's Involvement in Legislative Discussions |url=http://www.nationaljournal.com/congress/the-evolution-of-the-nra-s-defense-of-guns-20121221 |journal=National Journal |access-date=March 29, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150909204022/http://www.nationaljournal.com/congress/the-evolution-of-the-nra-s-defense-of-guns-20121221 |archive-date=September 9, 2015 |url-status=dead}}</ref> After the GCA, more strident groups, such as the ] (GOA), began to advocate for gun rights.<ref name=Greenblatt121221>{{cite news |last=Greenblatt |first=Alan |date=December 21, 2012 |title=The NRA Isn't The Only Opponent Of Gun Control |url=https://www.npr.org/2012/12/21/167780782/the-nra-isnt-the-only-opponent-of-gun-control |publisher=NPR |access-date=March 29, 2014 |archive-date=March 30, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140330221328/http://www.npr.org/2012/12/21/167780782/the-nra-isnt-the-only-opponent-of-gun-control |url-status=live }}</ref> According to the GOA, it was founded in 1975 when "the radical left introduced legislation to ban all handguns in California."<ref name="hlrichardson-GOA">{{cite web |url=http://gunowners.org/hlrichardson.htm |title=H.L. "Bill" Richardson – GOA |access-date=March 28, 2014}}</ref> The GOA and other national groups like the ] (SAF) and its offshoot the ] (FPC), ] (JPFO), and the ] (SAS), often take stronger stances than the NRA and criticize its history of support for some firearms legislation, such as GCA. The ] (NAGR) has been an outspoken critic of the NRA for a number of years. According to the Huffington Post, "NAGR is the much leaner, more pugnacious version of the NRA. Where the NRA has looked to find some common ground with gun reform advocates and at least appear to be reasonable, NAGR has been the unapologetic champion of opening up gun laws even more."<ref>{{Cite web|date=2016-08-01|title=How Republican Gun Legislation Died In Congress|url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/republican-gun-bill-died-congress_n_579fa095e4b0e2e15eb6baba|access-date=2022-02-16|website=HuffPost|language=en|archive-date=February 16, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220216221748/https://www.huffpost.com/entry/republican-gun-bill-died-congress_n_579fa095e4b0e2e15eb6baba|url-status=live}}</ref> These groups believe any compromise leads to greater restrictions.<ref name=Singh2003>{{cite book |last=Singh |first=Robert P. |year=2003 |title=Governing America: The Politics of a Divided Democracy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hv5TeKbXbpkC |publisher=Oxford University |isbn=978-0199250493 |oclc=248877185 }}</ref>{{rp|368}}<ref name=Tatalovich-Daynes>{{cite book |year=2005 |editor1-last=Tatalovich |editor1-first=Raymond |editor2-last=Daynes |editor2-first=Byron W. |title=Moral Controversies in American Politics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=chGqngEACAAJ |location=Armonk, New York |publisher=M.E. Sharpe |isbn=978-0765614209 }}</ref>{{rp|172}} | |||

| A milestone in gun control legislation was the ], the first post World war II federal firearms related law passed by Congress. In the latter decades of the 20th Century, groups such as the ] (NRA) and the ] (GOA) organized voters and campaign volunteers to focus citizen communication and interest when firearm legislation was under consideration, both at federal and state levels. | |||

| According to the authors of ''The Changing Politics of Gun Control'' (1998), in the late 1970s, the NRA changed its activities to incorporate political advocacy.<ref name=changingpolitics>{{cite book|title=The Changing Politics of Gun Control|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|isbn=978-0847686155|page=|author1=Bruce, John M.|author2=Wilcox, Clyde|date=1998|url=https://archive.org/details/changingpolitics0000unse/page/159}}</ref> Despite the impact on the volatility of membership, the politicization of the NRA has been consistent and the NRA-Political Victory Fund ranked as "one of the biggest spenders in congressional elections" as of 1998.<ref name=changingpolitics/> According to the authors of ''The Gun Debate'' (2014), the NRA taking the lead on politics serves the gun industry's profitability. In particular when gun owners respond to fears of gun confiscation with increased purchases and by helping to isolate the industry from the misuse of its products used in shooting incidents.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Gun Debate: What Everyone Needs to Know|date=2014|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=201|author=Cook, Philip J. |author2=Goss, Kristin A. |author-link2=Kristin Goss}}</ref> | |||

| The United States was generally seen as having the least stringent gun control laws in the developed world, with the possible exception of Switzerland, in part due to the strength of the gun lobby, particularly the NRA.<ref name="isbn1-55111-252-3">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Thomas, David C. | |||

| |title=Canada and the United States: Differences that Count, Second Edition | |||

| |publisher=Broadview Press | |||

| |location=Peterborough, Ontario | |||

| |year=2000 | |||

| |page=71 | |||

| |isbn=1-55111-252-3 | |||

| |url=http://books.google.com/?id=yPVwbeM64i8C&pg=PA71&dq=%22United+States+has+the+weakest+gun+control+laws+in+the%22+%22developed+world%22++%22due+to+the+strength+of+the+gun+lobby,+and+in%22+%22particular+the+National+Rifle+Association%22 | |||

| }}</ref> The NRA has traditionally supported gun laws intended to prevent criminals from obtaining firearms, while opposing new restrictions that affected law-abiding citizens. | |||

| The ] began in 1974 as Handgun Control Inc. (HCI). Soon after, it formed a partnership with another fledgling group called the National Coalition to Ban Handguns (NCBH) – later known as the ] (CSGV). The partnership did not last, as NCBH generally took a tougher stand on gun regulation than HCI.<ref name=Bruce-Wilcox1998Ch10>{{cite book |last=Lambert |first=Diana |year=1998 |chapter=Trying to Stop the Craziness of This Business: Gun Control Groups |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VvNb5s8Z3b0C&pg=PA172|editor1-last=Bruce |editor1-first=John M. |editor2-last=Wilcox |editor2-first=Clyde |title=The Changing Politics of Gun Control |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VvNb5s8Z3b0C |location=Lanham, Maryland |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|isbn=978-0847686155 |oclc=833118449}}</ref>{{rp|186}} In the wake of the 1980 ], HCI saw an increase of interest and fundraising and contributed $75,000 to congressional campaigns. Following the Reagan assassination attempt and the resultant injury of ], ] joined the board of HCI in 1985. HCI was renamed in 2001 to Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.<ref name="spitzerCh4">Spitzer, Robert J.: ''The Politics of Gun Control''. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995</ref> | |||

| {{main|National_Rifle_Association#Political_advocacy}} | |||

| =====Centers for Disease Control (CDC) restriction===== | |||

| An important electoral showdown over gun control came in 1970, when ] ] (], ]), who had highlighted crime in the ] and sponsored the ], was defeated for reelection. | |||

| In 1996, Congress added language to the relevant appropriations bill which required "none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the ] may be used to advocate or promote gun control."<ref>''Making omnibus consolidated appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1997, and for other purposes'' </ref> This language was added to prevent the funding of research by the CDC that gun rights supporters considered politically motivated and intended to bring about further gun control legislation. In particular, the NRA and other gun rights proponents objected to work supported by the ], then run by ], including research authored by ].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/26/us/26guns.html?pagewanted=1&_r=0 |title=N.R.A. Stymies Firearms Research, Scientists Say |date=January 25, 2011 |author=Michael Luo |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=February 5, 2013 |archive-date=February 27, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130227192911/http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/26/us/26guns.html?pagewanted=1&_r=0 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nraila.org//Issues/FactSheets/Read.aspx?ID=119 |title=22 Times Less Safe? Anti-Gun Lobby's Favorite Spin Re-Attacks Guns In The Home |publisher=NRA-ILA |date=December 11, 2001 |access-date=February 5, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141129074157/http://www.nraila.org//Issues/FactSheets/Read.aspx?ID=119 |archive-date=November 29, 2014 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Obama Lifts Ban on Funding Gun Violence Research |date=January 16, 2013 |author=Eliot Marshall |newspaper=ScienceInsider |publisher=American Association for the Advancement of Science |access-date=February 5, 2013 |url=http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2013/01/obama-lifts-ban-on-funding-gun-v.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130206142921/http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2013/01/obama-lifts-ban-on-funding-gun-v.html |archive-date=February 6, 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ===21st century=== | |||

| The GOA organization originated from dissatisfaction with the NRA. The group has historically rejected any gun laws that infringed the rights of law-abiding citizens, putting it at odds with the NRA on many legislative issues. | |||

| ] | |||

| In October 2003, the ] published a report on the effectiveness of gun violence prevention strategies that concluded "Evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of any of these laws."<ref name=CDC2003>{{cite journal |date=October 3, 2003 |title=First Reports Evaluating the Effectiveness of Strategies for Preventing Violence: Firearms Laws. Findings from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services |url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5214.pdf |journal=MMWR |volume=52 |issue=RR-14 |pages=11–20 |issn=1057-5987 |pmid=14566221 |last1=Hahn |first1=R. A. |last2=Bilukha |first2=O. O. |last3=Crosby |first3=A |last4=Fullilove |first4=M. T. |last5=Liberman |first5=A |last6=Moscicki |first6=E. K. |last7=Snyder |first7=S |last8=Tuma |first8=F |last9=Briss |first9=P |author10=Task Force on Community Preventive Services |archive-date=July 8, 2017 |access-date=September 9, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170708164255/https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5214.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|14}} A similar survey of firearms research by the ] arrived at nearly identical conclusions in 2004.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-first=Charles F |editor1-last=Wellford |editor2-first=John V |editor2-last=Pepper |editor3-first=Carol V |editor3-last=Petrie |title=Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review |year=2004 |url=http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10881&page=2 |edition=Electronic |orig-date=Print ed. 2005 |publisher=National Academies Press |location=Washington, D.C. |isbn=978-0309546409 |page=97 |doi=10.17226/10881 |archive-date=March 29, 2014 |access-date=March 29, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140329082811/http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10881&page=2 |url-status=live }}</ref> In September of that year, the Assault Weapons Ban expired due to a ]. Efforts by gun control advocates to renew the ban failed, as did attempts to replace it after it became defunct. | |||

| The NRA opposed bans on handguns in Chicago, Washington D.C., and San Francisco while supporting the ] (also known as the School Safety And Law Enforcement Improvement Act), which strengthened requirements for background checks for firearm purchases.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Williamson |first1=Elizabeth |last2=Schulte |first2=Brigid |date=December 20, 2007 |title=Congress Passes Bill to Stop Mentally Ill From Getting Guns |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/19/AR2007121902279.html |newspaper=The Washington Post |location=Washington, D.C. |quote=Congress yesterday approved legislation that would help states more quickly and accurately identify potential firearms buyers with mental health problems that disqualify them from gun ownership under federal law.... drew overwhelming bipartisan support, and the backing of both the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence and the National Rifle Association. |archive-date=December 3, 2017 |access-date=August 29, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171203153505/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/19/AR2007121902279.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The GOA took issue with a portion of the bill, which they termed the "Veterans' Disarmament Act."<ref>{{cite news |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=November 5, 2007 |title=Vets worry bill blocks gun purchases |url=http://www.lvrj.com/news/11017156.html |newspaper=Las Vegas Review-Journal |location=Las Vegas |access-date=March 11, 2013 |archive-date=April 10, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080410180653/http://www.lvrj.com/news/11017156.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Besides the GOA, other national gun rights groups often took a stronger stance than the NRA. These groups criticize the NRA's history of support for some gun control legislation, such as the Gun Control Act of 1968. Some of these groups are the ], ], and ]. These groups, like the GOA, believe any compromise leads to incrementally greater restrictions.<ref name="isbn0-19-925049-9">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Singh, Robert P. | |||

| |title=Governing America: the politics of a divided democracy | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |location=Oxford | |||

| |year=2003 | |||

| |page=368 | |||

| |isbn=0-19-925049-9 | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="ISBN 0765614200">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Daynes, Byron W.; Tatalovich, Raymond | |||

| |title=Moral controversies in American politics | |||

| |publisher=M.E. Sharpe | |||

| |location=Armonk, N.Y. | |||

| |year=2005 | |||

| |page=172 | |||

| |isbn=0-7656-1420-0 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ]. ] and police officer ] lie wounded on the ground.]] | |||

| ] (HCI), founded in 1974 by businessman Pete Shields, formed a partnership with the ] (NCBH), also founded in 1974. Soon parting ways, the NCBH was renamed the ] in 1990, and while smaller than HCI, generally took a tougher stand on gun regulation than HCI.<ref name="isbn0-8476-8615-9">{{cite book | |||

| |author=Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. | |||

| |title=The changing politics of gun control | |||

| |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield | |||

| |location=Lanham, Md | |||

| |year=1998 | |||

| |page=183 | |||

| |isbn=0-8476-8615-9 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Besides the GOA, other national gun rights groups continue to take a stronger stance than the NRA. These groups include the Second Amendment Sisters, Second Amendment Foundation, Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership, and the ]. New groups have also arisen, such as the ], which grew largely out of safety-issues resulting from the creation of ] that were legislatively mandated amidst a response to widely publicized ]. | |||

| HCI saw an increase of interest and fund raising in the wake of the 1980 murder of ]. By 1981 membership exceeded 100,000. Measured in dollars contributed to congressional campaigns, HCI contributed $75,000. Following the ], and the resultant injury of ], ] joined the board of HCI in 1985. HCI was renamed in 2001 to ].<ref name="spitzerCh4">Spitzer, Robert J.: ''The Politics of Gun Control''. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995</ref> | |||