| Revision as of 16:14, 9 March 2012 editIloveandrea (talk | contribs)4,026 edits Undid revision 480943711 by Volunteer Marek (talk)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:54, 16 January 2025 edit undoRich Farmbrough (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors1,725,970 edits →Legacy: Copyedit. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Anti- colonial Insurgency in Kenya from 1952 to 1960}} | |||

| {{POV|date=March 2012}} | |||

| {{About|the conflict in Kenya||Mau Mau (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2011}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date= |

{{Use British English|date=March 2013}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2022}} | |||

| {{Hatnote||"Mau Mau" redirects here. For other uses, see ].}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| |conflict=Mau Mau |

| conflict = Mau Mau rebellion | ||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |date=1952–1960 | |||

| | image = KAR Mau Mau.jpg | |||

| |place=] | |||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| |result= British military victory | |||

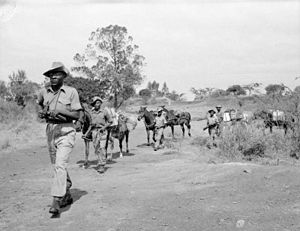

| | caption = Troops of the ] on watch for Mau Mau rebels | |||

| |combatant1='''Mau Mau'''<ref name="anderson2005"/><ref name="maloba1993"/>{{ref label|Note1|A|A}} | |||

| | date = '''Main Conflict'''<br>7 October, 1952 – 21 October 1956<br>'''Mau Mau Remnants'''<br>1956 – 1960 | |||

| |combatant2=] ]<br>] ] | |||

| | place = ] | |||

| |commander1=* ]<br>* ]<br>* ]<br>* ] | |||

| | result = British victory | |||

| |commander2=* ] Sir ] (Governor)<br>* ] General Sir ]<br>* ] ] (Chief Justice) | |||

| * Rebellion suppressed | |||

| |strength1=Unknown | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flag|United Kingdom}} | |||

| |strength2=10,000 regular troops (African and British); 21,000 police; 25,000 Kikuyu Home Guard<ref name="page1996_206">], p. 206.</ref><ref name="anderson2005_5">], p. 5.</ref> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of Kenya (1921–1963).svg}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of the Uganda Protectorate.svg}} ] | |||

| |casualties1='''Mau Mau''': | |||

| * {{flag|Southern Rhodesia}} | |||

| '''Killed''': 12,000 officially; 20,000+ unofficially<ref name="anderson2005_4"/><br/ > | |||

| | combatant2 = Mau Mau rebels{{efn|The name '']'' is sometimes heard in connection with Mau Mau. KLFA was the name that Dedan Kimathi used for a coordinating body which he tried to set up for Mau Mau. It was also the name of another militant group that sprang up briefly in the spring of 1960; the group was broken up during a brief operation from 26 March to 30 April.<ref name="Nissimi 2006 11">{{Harvnb|Nissimi|2006|p=11}}.</ref>}} | |||

| '''Captured''': 2,633<br/ > | |||

| * ] | |||

| '''Surrendered''': 2,714 | |||

| ---- | |||

| ] Bands (from 1954)<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40402312|title=Revolt and Repression in Kenya: The "Mau Mau" Rebellion, 1952-1960|first=John|last=Newsinger|date=1981 |issue=2 |journal=Science & Society|volume=45 |pages=159–185 |jstor=40402312 }}</ref> | |||

| |casualties2='''British and African security forces''': | |||

| | commander1 = {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>(1951–1955)<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>(1955–1957)<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>(1957–1960)<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br>{{flagicon image|Flag of Kenya (1921–1963).svg}} ]<br>{{flagicon image|Flag of Kenya (1921–1963).svg}} ] | |||

| '''Killed''': 200<br/ > | |||

| | commander2 = ]{{executed}}<br>]<br>]<br>]{{MIA}}<br>]{{executed}} | |||

| '''Wounded''': 579<br/ > | |||

| | strength1 = 10,000 regular troops<br>21,000 police<br>25,000 ]<ref name = "Page 2011 p206">{{Harvnb|Page|2011|p=206}}.</ref>{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=5}} | |||

| '''Surrendered''': n/a | |||

| | strength2 = 35,000+ insurgents<ref>Durrani, Shiraz. Mau Mau, the Revolutionary, Anti-Imperialist Force from Kenya, 1948–63: Selection from Shiraz Durrani's Kenya's War of Independence: Mau Mau and Its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948–1990. Vita Books, 2018. | |||

| </ref> | |||

| |casualties3='''Civilians''' | |||

| | casualties1 = 3,000 native Kenyan police and soldiers killed<ref name="Elstein 07Apr2011">{{cite web |url=http://www.opendemocracy.net/david-elstein/daniel-goldhagen-and-kenya-recycling-fantasy |title=Daniel Goldhagen and Kenya: recycling fantasy |author=David Elstein |author-link=David Elstein |date=7 April 2011 |publisher=openDemocracy.org |access-date=8 March 2012 |archive-date=15 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181215172234/http://www.opendemocracy.net/david-elstein/daniel-goldhagen-and-kenya-recycling-fantasy |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| '''Victims of Mau Mau''':<ref name="page1996_206"/><ref name="anderson2005_84">], p. 84.</ref><br/ > | |||

| 95 British military personnel killed<ref> ""UK armed forces Deaths: Operational deaths post World War II"" (PDF). Ministry of defense. 25 March 2021</ref> | |||

| <small>These figures do not include the many hundreds of Africans who 'disappeared', and whose bodies were never found.</small><br/ > | |||

| | casualties2 = 12,000–20,000+ killed (including 1,090 executed){{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=4}}<br>2,633 captured<br>2,714 surrendered | |||

| '''Africans killed''': 1,819<br/ > | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Mau Mau Uprising}} | |||

| '''Africans wounded''': 916<br/ > | |||

| '''Asians killed''': 26<br/ > | |||

| '''Asians wounded''': 36<br /> | |||

| '''Europeans killed''': 32<br/ > | |||

| '''Europeans wounded''': 26<br/ > | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{British Colonial Emergencies}} | |||

| The '''Mau Mau rebellion''' (1952–1960), also known as the '''Mau Mau uprising''', '''Mau Mau revolt''', or '''Kenya Emergency''', was a war in the British ] (1920–1963) between the ] (KLFA), also known as the Mau Mau, and the British authorities.<ref>{{cite book |last=Blakeley |first=Ruth |title=State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rft8AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA80 |year=2009 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-04246-3}}</ref> Dominated by ], ] and ] fighters, the KLFA also comprised units of ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Osborne |first=Myles |date=2010 |title=The Kamba and Mau Mau: Ethnicity, Development, and Chiefship, 1952–1960 |journal=The International Journal of African Historical Studies |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=63–87 |jstor=25741397 |issn=0361-7882}}</ref> and ] who fought against the European colonists in Kenya - the ], and the local ] (British colonists, local auxiliary militia, and pro-British Kikuyu).{{sfn|Anderson|2005}}{{efn|In English, the Kikuyu people also are known as the "Kikuyu" and as the "Wakikuyu" people, but their preferred ] is "Gĩkũyũ", derived from the ].}} | |||

| The capture of Field Marshal ] on 21 October 1956 signalled the defeat of the Mau Mau, and essentially ended the British military campaign.<ref>''The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army'' (1994) p. 350</ref> However, the rebellion survived until after Kenya's independence from Britain, driven mainly by the ] units led by Field Marshal ]. General Baimungi, one of the last Mau Mau leaders, was killed shortly after Kenya attained self-rule.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,875584,00.html |title=Kenya: A Love for the Forest |date=17 January 1964 |magazine=Time |access-date=12 February 2018 |language=en-US |issn=0040-781X |archive-date=23 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200423115834/http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,875584,00.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The KLFA failed to capture wide public support.<ref>''The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army'' (1994) p. 346.</ref> ], in ''The Mau Mau War in Perspective'', suggests this was due to a British ] strategy,<ref name="Mumford 2012 p49">{{Harvnb|Mumford|2012|p=}}.</ref> which they had developed in suppressing the ] (1948–60).<ref name="Füredi 1989 5">{{Harvnb|Füredi|1989|p=5}}</ref> The Mau Mau movement remained internally divided, despite attempts to unify the factions. On the colonial side, the uprising created a rift between the European colonial community in Kenya and the ],<ref name="Maloba 1998">{{Harvnb|Maloba|1998}}.</ref> as well as violent divisions within the ] community:{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=4}} "Much of the struggle tore through the African communities themselves, an internecine war waged between rebels and 'loyalists' – Africans who took the side of the government and opposed Mau Mau."<ref name="Branch 2009 pxii">{{Harvnb|Branch|2009|p=}}.</ref> Suppressing the Mau Mau Uprising in the Kenyan colony cost Britain £55 million<ref name="Gerlach 2010 213">{{Harvnb|Gerlach|2010|p=}}.</ref> and caused at least 11,000 ] among the Mau Mau and other forces, with some estimates considerably higher.<ref name="Bloody uprising of the Mau Mau">{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12997138|title=Bloody uprising of the Mau Mau|date=7 April 2011|publisher=BBC News|access-date=23 July 2019|language=en-GB|archive-date=2 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200102004920/https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12997138|url-status=live}}</ref> This included 1,090 executions by hanging.<ref name="Bloody uprising of the Mau Mau" /> | |||

| The '''Mau Mau Uprising''' (also known as the '''Mau Mau Revolt''', '''Mau Mau Rebellion''' and the '''Kenya Emergency''') was a military conflict that took place in ]{{ref label|Note2|B|B}} between 1952 and 1960. It involved a ]-dominated anti-colonial group called ''Mau Mau'' and elements of the ], auxiliaries and anti-Mau Mau Kikuyu.<ref name="anderson2005">].</ref><ref name="elkins2005">].</ref> | |||

| __TOC__ | |||

| The movement was unable to capture widespread public support.<ref>''The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army'' (1994) p. 346</ref> The capture of rebel leader ] on 21 October 1956 signalled the ultimate defeat of the Mau Mau uprising, and essentially ended the British military campaign.<ref>''The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Army'' (1994) p. 350</ref> | |||

| The conflict arguably set the stage for Kenyan independence in December 1963.<ref name="percox2005_751-752">{{cite encyclopedia | |||

| |last=Percox|first=David A|editor-first=Kevin|editor-last=Shillington|year=2005|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of African History, Volume 1, A–G|location=New York|publisher=Fitzroy Dearborn|pages=|title=Kenya: Mau Mau Revolt|isbn=1579582451|quote=The Mau Mau revolt forced the British government to institute political and economic reforms in Kenya}}</ref> It created a rift between the European colonial community in Kenya and the ] in London,<ref name="maloba1993">].</ref> but also resulted in violent divisions within the Kikuyu community.<ref name="anderson2005_4">], p. 4. "Much of the struggle tore through the African communities themselves, an internecine war waged between rebels and so-called 'loyalists'—Africans who took the side of the government and opposed Mau Mau."</ref><ref name="branch2009_xii">], p. </ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| {{History of Kenya}}] | |||

| The origin of the term ''Mau Mau'' is uncertain. According to some members of Mau Mau, they never referred to themselves as such, instead preferring the military title Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA).<ref name="kanogo1992_23-25">], pp. 23–5.</ref> Some publications, such as Fred Majdalany's ''State of Emergency: The Full Story of Mau Mau'', claim that it was an anagram of ''Uma Uma'' (which means "get out get out") and was a military codeword based on a secret language-game Kikuyu boys used to play at the time of their circumcision. Majdalany goes on to state that the British simply used the name as a label for the ] ethnic community without assigning any specific definition.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last= Majdalany | |||

| | first = Fred | |||

| | title = State of Emergency: The Full Story of Mau Mau | |||

| | publisher=Houghton Mifflin | |||

| | location = Boston | |||

| | year = 1963 | |||

| | page = 75}}</ref> | |||

| The origin of the term Mau Mau is uncertain. According to some members of Mau Mau, they never referred to themselves as such, instead preferring the military title Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA).<ref name="Kanogo 1992 23to25">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1992|pp=23–25}}.</ref> Some publications, such as Fred Majdalany's ''State of Emergency: The Full Story of Mau Mau'', claim it was an anagram of ''Uma Uma'' (which means "Get out! Get out!") and was a military codeword based on a secret language game Kikuyu boys used to play at the time of their circumcision. Majdalany also says the British simply used the name as a label for the Kikuyu ethnic community without assigning any specific definition.<ref name="Majdalany 1963 75">{{Harvnb|Majdalany|1963|p=75}}.</ref> However, there was a ] in ]/Tanzania in 1905/6, ('Maji' meaning 'water' after a 'water-medicine') so this may be the origin of Mau Mau. | |||

| As the movement progressed, a ] acronym was adopted: "] Aende Ulaya, Mwafrika Apate Uhuru" meaning "Let the European go back to Europe (Abroad), Let the African regain Independence".<ref name="kariuki1960_167">], p. 167.</ref> J.M. Kariuki, a member of Mau Mau who was detained during the conflict, postulates that the British preferred to use the term ''Mau Mau'' instead of ''KLFA'' in an attempt to deny the Mau Mau rebellion international legitimacy.<ref name="kariuki1960_24">], p. 24.</ref> Kariuki also wrote that the term ''Mau Mau'' was adopted by the rebellion in order to counter what they regarded as colonial propaganda.<ref name="kariuki1960_167"/> | |||

| As the movement progressed, a ] ] was adopted: "] Aende Ulaya, Mwafrika Apate Uhuru", meaning "Let the foreigner go back abroad, let the African regain independence".<ref name="Kariuki 1960 167">{{Harvnb|Kariuki|1975|p=167}}.</ref> J. M. Kariuki, a member of Mau Mau who was detained during the conflict, suggests the British preferred to use the term Mau Mau instead of KLFA to deny the Mau Mau rebellion international legitimacy.<ref name="Kariuki 1960 24">{{Harvnb|Kariuki|1975|p=24}}.</ref> Kariuki also wrote that the term Mau Mau was adopted by the rebellion in order to counter what they regarded as colonial propaganda.<ref name="Kariuki 1960 167"/> | |||

| ==Nature of the rebellion== | |||

| The contemporary view saw Mau Mau as a savage, violent, and depraved tribal cult, an expression of unrestrained emotion rather than reason. Mau Mau allegedly sought to turn the Kikuyu people back to "the bad old days" before British rule.<ref name="berman1991_182-183">], p. 182–3.</ref> The British attempt at understanding the revolt involved soliciting the advice of purported experts on the Kikuyu and the "African mind" such as ] and JC Carothers.<ref name="mcculloch1995_64to76">], pp. .</ref> | |||

| Author and activist ] indicates that, to her, the most interesting story of the origin of the name is the Kikuyu phrase for the beginning of a list. When beginning a list in Kikuyu, one says, "''maũndũ ni mau''{{-"}}, "the main issues are...", and holds up three fingers to introduce them. Maathai says the three issues for the Mau Mau were land, freedom, and self-governance.<ref>{{cite book |title=Unbowed: a memoir |author=Wangari Maathai |page=63 |publisher=Alfred A. Knopf |date=2006 |isbn=0307263487}}</ref> | |||

| By the mid-1960s, this view was being challenged by memoirs of former Mau Mau members and leaders that portrayed Mau Mau as an essential, if radical, component of African nationalism in Kenya, and by academic studies that analysed Mau Mau as a modern and nationalist response to the unfairness and oppression of colonial domination (though such studies downplayed the specifically Kikuyu nature of the movement).<ref name="berman1991_183-185">], p. 183–5.</ref> | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| There continues to be vigorous debate within Kenyan society and among the academic community within and without Kenya regarding the nature of Mau Mau and its aims, as well as the response to and effects of the uprising.<ref name="clough1998_4">], p. </ref><ref name="branch2009_3">], p. </ref> Nevertheless, as many Kikuyu fought against Mau Mau on the side of the colonial government as joined them in rebellion<ref name="branch2009_xii"/> and, partly because of this, the conflict is now often regarded in academic circles as an intra-Kikuyu civil war,<ref name="anderson2005_4"/><ref name="branch2009_3"/> a characterisation that remains extremely unpopular in Kenya.<ref name="bbc_07042011">{{cite news |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-12997138 |title=Mau Mau uprising: Bloody history of Kenya conflict |newspaper=BBC News |date=7 April 2011 |accessdate=12 May 2011 |quote=There was lots of suffering on the other side too. This was a dirty war. It became a civil war—though that idea remains extremely unpopular in Kenya today.}} (The quote is of Professor David Anderson).</ref> Some academics argue that the reason the revolt was essentially limited to the Kikuyu people was, in part, that they were the hardest hit by British colonialism and its effects.<ref name="berman1991_196">], p. 196. "The impact of colonial capitalism and the colonial state hit the Kikuyu with greater force and effect than any other of Kenya's peoples, setting off new processes of differentiation and class formation."</ref> | |||

| regards the rise of the Mau Mau movement as "without doubt, one of the most important events in recent African history."<ref name="thomas1993">{{cite journal|last=Thomas|first=Beth|year=1993|url=http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/36/index-ba.html|page=7|title=Historian, Kenya native's book on Mau Mau revolt|journal=UpDate|volume=13|issue=13}}</ref> Oxford's , however, considers Maloba's and similar work to be the product of "swallowing too readily the propaganda of the Mau Mau war",<ref name="anderson2005_10">], p. 10.</ref> noting the similarity between such analysis and the "simplistic"<ref name="anderson2005_10"/> earlier studies of Mau Mau. This earlier work cast the Mau Mau war in strictly bipolar terms, "as conflicts between anti-colonial nationalists and colonial collaborators".<ref name="anderson2005_10"/> Harvard's ]' 2005 ] has met similar criticism, as well as being criticised for sensationalism.<ref name="elstein">See in particular David Elstein's angry letters: | |||

| * {{cite journal |author= |year=2005 |title=Letters: Tell me where I'm wrong |journal=London Review of Books |volume=27 |issue=11 |url=http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n11/letters |accessdate=3 May 2011}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |author=David Elstein |year=2005 |title=The End of the Mau Mau |journal=The New York Review of Books |volume=52 |issue=11 |url=http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2005/jun/23/the-end-of-the-mau-mau |accessdate=3 May 2011}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |author=David Elstein |year=2005 |title=Letters: Tell me where I'm wrong |journal=London Review of Books |volume=27 |issue=14 |url=http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n14/letters |accessdate=3 May 2011}} | |||

| It is worth noting that while David Elstein regards the "requirement" for the "great majority of Kikuyu" to live inside 800 "fortified villages" as "serv the purpose of protection", Professor David Anderson (amongst others) regards the "compulsory resettlement" of "1,007,500 Kikuyu" inside what, for the "most" part, were "little more than concentration camps" as "punitive . . . to punish Mau Mau sympathisers". See his and ], p. 294.</ref><ref name="ogot2005">]. "There was no reason and no restraint on both sides, although Elkins sees no atrocities on the part of Mau Mau."</ref> | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| | title = | |||

| | quote = It is often assumed that in a conflict there are two sides in opposition to one another, and that a person who is not actively committed to one side must be supporting the other. During the course of a conflict, leaders on both sides will use this argument to gain active support from the "crowd". In reality, conflicts involving more than two persons usually have more than two sides, and if a resistance movement is to be successful, propaganda and politicization are essential.<ref name="pirouet1977_197">{{cite book|last=Pirouet|chapter=Armed Resistance and Counter-Insurgency: Reflections on the Anya Nya and Mau Mau Experiences|editor-last=Mazrui|editor-first=Ali A|title=The Warrior Tradition in Modern Africa|year=1977|page=}}</ref> | |||

| | source = —Louise Pirouet | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 40% | |||

| | fontsize = 85% | |||

| | bgcolor = AliceBlue | |||

| | style = | |||

| | title_bg = | |||

| | title_fnt = | |||

| | tstyle = text-align: left; | |||

| | qalign = right | |||

| | qstyle = text-align: left; | |||

| | quoted = yes | |||

| | salign = right | |||

| | sstyle = text-align: right;}} | |||

| Throughout ] history, there have been two traditions: ''moderate-conservative'' and ''radical''.<ref name="clough1998">].</ref> Despite the differences between them, there has been a continuous debate and dialogue between these traditions, leading to a great political awareness among the Kikuyu.<ref name="clough1998"/><ref name="berman1991_197">], p. 197. "eveloping conflicts . . . in Kikuyu society were expressed in a vigourous internal debate."</ref> By 1950, these differences, and the impact of colonial rule, had given rise to three African political blocks: ''conservative'', ''moderate nationalist'' and ''militant nationalist''.<ref name="anderson2005_11-12">], pp. 11–2.</ref> It has also been argued that Mau Mau was not explicitly national, either intellectually or operationally;<ref name="branch2009_xi"/> Bruce Berman argues that, "While Mau Mau was clearly not a tribal atavism seeking a return to the past, the answer to the question of "was it nationalism?" must be yes and no."<ref name="berman1991_199">], p. 199.</ref> As the Mau Mau rebellion wore on, the violence forced the spectrum of opinion within the Kikuyu, Embu and Meru to polarise and harden into the two distinct camps of loyalist and Mau Mau.<ref name="branch2009_1">], p. </ref> This neat division between loyalists and Mau Mau was a product of the conflict, rather than a cause or catalyst of it, with the violence becoming less ambiguous over time,<ref name="branch2009_2">], p. </ref> in a similar manner to other situations.<ref name="pirouet1977_200">{{cite book|last=Pirouet|first=Louise|chapter=Armed Resistance and Counter-Insurgency: Reflections on the Anya Nya and Mau Mau Experiences|editor-last=Mazrui|editor-first=Ali A|title=The Warrior Tradition in Modern Africa|year=1977|location=Leiden|publisher=Brill|isbn=9004056467|page=|quote=}}</ref><ref name="kalyvas2006">].</ref> | |||

| ==Kenya before the Emergency== | |||

| {{Quote box | {{Quote box | ||

| |quote = The principal item in the natural resources of Kenya is the land, and in this term we include the colony's mineral resources. It seems to us that our major objective must clearly be the preservation and the wise use of this most important asset. |

|quote = The principal item in the natural resources of Kenya is the land, and in this term we include the colony's mineral resources. It seems to us that our major objective must clearly be the preservation and the wise use of this most important asset.{{sfn|Curtis|2003|p=320}} | ||

| |source = —Deputy Governor to Secretary of State<br>for the Colonies, 19 March 1945 | |source = —Deputy Governor to Secretary of State<br />for the Colonies, 19 March 1945 | ||

| |align = right | |align = right | ||

| |width = 42% | |width = 42% | ||

| Line 99: | Line 58: | ||

| |bgcolor = AliceBlue | |bgcolor = AliceBlue | ||

| |style = bold | |style = bold | ||

| |title_bg = | |||

| |title_fnt = | |||

| |tstyle = text-align: left; | |tstyle = text-align: left; | ||

| |qalign = right | |qalign = right | ||

| Line 107: | Line 64: | ||

| |salign = right | |salign = right | ||

| |sstyle = text-align: right; | |sstyle = text-align: right; | ||

| }} | |||

| }}The primary British interest in Kenya was its land which, observed the British East Africa Commission of 1925, constituted "some of the richest agricultural soils in the world, mostly in districts where the elevation and climate make it possible for Europeans to reside permanently."<ref name="eac1925_149">], p. 149.</ref> Though declared a colony in 1920, the formal British colonial presence in Kenya began with a proclamation on 1 July 1895, in which Kenya was claimed as a British ].<ref name="alam2007_1">], p. 1. "The colonial presence in Kenya, in contrast to, say, India, where it lasted almost 200 years, was brief but equally violent. It formally started when Her Majesty's agent and Counsel General at Zanzibar, A.H. Hardinge, in a proclamation on 1 July 1895, announced that he was taking over the ] as well as the interior that included the Kikuyu land, now known as Central Province."</ref> | |||

| The armed rebellion of the Mau Mau was the culminating response to colonial rule.<ref name="Coray 1978 p179">{{Harvnb|Coray|1978|p=179}}: "The administration's refusal to develop mechanisms whereby African grievances against non-Africans might be resolved on terms of equity, moreover, served to accelerate a growing disaffection with colonial rule. The investigations of the Kenya Land Commission of 1932–1934 are a case study in such lack of foresight, for the findings and recommendations of this commission, particularly those regarding the claims of the Kikuyu of Kiambu, would serve to exacerbate other grievances and nurture the seeds of a growing African nationalism in Kenya".</ref>{{sfn|Anderson|2005|pp=15, 22}} Although there had been previous instances of violent resistance to colonialism, the Mau Mau revolt was the most prolonged and violent anti-colonial warfare in the British Kenya colony. From the start, the land was the primary British interest in Kenya,{{sfn|Curtis|2003|p=320}} which had "some of the richest agricultural soils in the world, mostly in districts where the elevation and climate make it possible for Europeans to reside permanently".<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p149">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=149}}.</ref> Though declared a colony in 1920, the formal British colonial presence in Kenya began with a proclamation on 1 July 1895, in which Kenya was claimed as a British ].<ref name="Alam 2007 p1">{{Harvnb|Alam|2007|p=1}}: The colonial presence in Kenya, in contrast to, say, India, where it lasted almost 200 years, was brief but equally violent. It formally started when Her Majesty's agent and Counsel General at Zanzibar, A.H. Hardinge, in a proclamation on 1 July 1895, announced that he was taking over the ] as well as the interior that included the Kikuyu land, now known as Central Province."</ref> | |||

| Even before 1895, however, Britain's presence in Kenya was marked by dispossession and violence. During the period in which Kenya's interior was being forcibly opened up for British settlement, an officer in the ] asserted, "There is only one way to improve the ] that is wipe them out; I should be only too delighted to do so, but we have to depend on them for food supplies",<ref name="elkins2005_3">], p. 3.</ref> and colonial officers such as ] wrote of how, on occasion, they ]d Kikuyu by the hundred.<ref>{{cite book |last=Meinertzhagen |first=Richard |title=Kenya Diary, 1902–1906 |year=1957 |location=London |publisher=Oliver and Boyd |pages=51–2}}</ref> This onslaught led ], in 1908, to remark: "surely it cannot be necessary to go on killing these defenceless people on such an enormous scale."<ref name="lapping1989_469">], p. 469.</ref> | |||

| Even before 1895, however, Britain's presence in Kenya was marked by ] and ]. In 1894, British MP ] had observed in the ], "The only person who has up to the present time benefited from our enterprise in the heart of Africa has been Mr. ]" (inventor of the ], the first automatic machine gun).<ref name="Ellis 1986 p100">{{Harvnb|Ellis|1986|p=}}.<br />You can read Dilke's speech in full here: {{Cite web |title= Class V; House of Commons Debate, 1 June 1894 |url= https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1894/jun/01/class-v#S4V0025P0_18940601_HOC_113 |work= ] |series= Series 4, Vol. 25, cc. 181–270 |date= 1 June 1894 |access-date= 11 April 2013 |archive-date= 15 December 2018 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20181215172307/https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1894/jun/01/class-v#S4V0025P0_18940601_HOC_113 |url-status= live }}</ref> During the period in which Kenya's interior was being forcibly opened up for British settlement, there was a great deal of conflict and British troops carried out atrocities against the native population.<ref name="Edgerton 1989 4">{{Harvnb|Edgerton|1989|p=4}}. Francis Hall, an officer in the ] and after whom ] was named, asserted: "There is only one way to improve the Wakikuyu that is wipe them out; I should be only too delighted to do so, but we have to depend on them for food supplies."</ref><ref name="Meinertzhagen 1957 51_52">{{Harvnb|Meinertzhagen|1957|pp=51–52}} ] wrote of how, on occasion, they massacred Kikuyu by the hundreds.</ref> | |||

| Kenyan resistance to British imperialism was there from the start—for example, the Kikuyu opposition of 1880–1900—and continued throughout the decades thereafter: the ] Revolt of 1895–1905;<ref name="alam2007_2">], p. 2.</ref> the ] Uprising of 1913–4;<ref name="alam2007_2"/> the women's revolt against forced labour in ] in 1947;<ref name="atieno1995_25">], p. </ref> and the Kalloa Affray of 1950.<ref name="ogot2003_15">], p. </ref> (Nor did Kenyan protest against colonial rule end with Mau Mau. For example, in the years that followed, a series of successful non-violent boycotts were carried out).<ref name="nissimi2006_10">], p. </ref> | |||

| Opposition to British imperialism had existed from the start of British occupation. The most notable include the ] led by ] of 1895–1905;<ref name="Alam 2007 p2">{{Harvnb|Alam|2007|p=2}}.</ref> the ] Uprising led by ] of 1913–1914;<ref name="Brantley 1981">{{Harvnb|Brantley|1981}}.</ref> the women's revolt against ] in ] in 1947;<ref name="Atieno-Odhiambo 1995 p25">{{Harvnb|Atieno-Odhiambo|1995|p=}}.</ref> and the Kolloa Affray of 1950.<ref name="Ogot 2003 15">{{Harvnb|Ogot|2003|p=}}.</ref> None of the armed uprisings during the beginning of British colonialism in Kenya were successful.<ref>{{Harvnb|Leys|1973|p=342}}, which notes they were "always hopeless failures. Naked spearmen fall in swathes before machine-guns, without inflicting a single casualty in return. Meanwhile, the troops burn all the huts and collect all the live stock within reach. Resistance once at an end, the leaders of the rebellion are surrendered for imprisonment ... Risings that followed such a course could hardly be repeated. A period of calm followed. And when unrest again appeared it was with other leaders ... and other motives." A particularly interesting example, albeit outside Kenya and featuring guns instead of spears, of successful armed resistance to maintain crucial aspects of autonomy is the ] of 1880–1881, whose ultimate legacy remains tangible even today, in the form of ].</ref> The nature of fighting in Kenya led ] to express concern about the scale of the fighting: "No doubt the clans should have been punished. 160 have now been killed outright ''without any further casualties on our side''.… It looks like a butchery. If the ] gets hold of it, all our plans in ] will be under a cloud. Surely it cannot be necessary to go on killing these defenceless people on such an enormous scale."<ref name="Maxon 1989 44">{{Harvnb|Maxon|1989|p=}}.</ref> | |||

| The Mau Mau rebellion can be regarded as a militant culmination of years of oppressive colonial rule and resistance to it,<ref name="coray1978">]. "The administration's refusal to develop mechanisms whereby African grievances against non-Africans might be resolved on terms of equity, moreover, served to accelerate a growing disaffection with colonial rule. The investigations of the Kenya Land Commission of 1932–1934 are a case study in such lack of foresight, for the findings and recommendations of this commission, particularly those regarding the claims of the Kikuyu of Kiambu, would serve to exacerbate other grievances and nurture the seeds of a growing African nationalism in Kenya".</ref><ref name="anderson2005_22">], p. 22.</ref> with its specific roots found in three episodes of Kikuyu history between 1920 and 1940.<ref name=anderson2005_15>], p. 15.</ref> All of this is not, of course, to say that Kikuyu society was perfect, stable and harmonious before the British arrived. The Kikuyu in the nineteenth century were expanding and colonising new territory and already internally divided between wealthy land-owning families and landless families, the latter dependent on the former in a variety of ways.<ref name="berman1991_196b">], p. 196. "In contrast to the constructed image of a stable and harmonious tradition, the Kikuyu in the nineteenth century were actively expanding and colonizing new territory and already internally divided between wealthy land-owning families and landless families attached to them in a variety of forms of dependence."</ref> | |||

| {{Quote box |quote = You may travel through the length and breadth of Kitui Reserve and you will fail to find in it any enterprise, building, or structure of any sort which Government has provided at the cost of more than a few sovereigns for the direct benefit of the natives. The place was little better than a wilderness when I first knew it 25 years ago, and it remains a wilderness to-day as far as our efforts are concerned. If we left that district {{Nowrap|to-morrow}} the only permanent evidence of our occupation would be the buildings we have erected for the use of our tax-collecting staff.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p187"/> |source = —Chief Native Commissioner of Kenya, 1925 |align = right |width = 39% |fontsize = 85% |bgcolor = AliceBlue |style = |title_bg = |title_fnt = |tstyle = text-align: left; |qalign = right |qstyle = text-align: left; |quoted = yes |salign = right |sstyle = text-align: right;}} | |||

| ===Economic deprivation of the Kikuyu=== | |||

| ] during the colonial period could own a disproportionate share of land.<ref name="Mosley 1983 5">{{Harvnb|Mosley|1983|p=}}.</ref> The first settlers arrived in 1902 as part of ]'s plan to have a settler economy pay for the ].{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=3}}<ref>{{Harvnb|Edgerton|1989|pp=1–5}}.<br />{{Harvnb|Elkins|2005|p=2}}, notes that the (British taxpayer) loans were never repaid on the Uganda Railway; they were written off in the 1930s.</ref> The success of this settler economy would depend heavily on the availability of land, labour and capital,<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1993|p=}}.</ref> and so, over the next three decades, the colonial government and settlers consolidated their control over Kenyan land, and forced native Kenyans to become ]ers. | |||

| {{Quote box | |||

| |quote = You may travel through the length and breadth of Kitui Reserve and you will fail to find in it any enterprise, building, or structure of any sort which Government has provided at the cost of more than a few sovereigns for the direct benefit of the natives. The place was little better than a wilderness when I first knew it 25 years ago, and it remains a wilderness to-day as far as our efforts are concerned. If we left that district to-morrow the only permanent evidence of our occupation would be the buildings we have erected for the use of our tax-collecting staff.<ref name ="eac1925_187"/> | |||

| |source = —Chief Native Commissioner of Kenya, 1925 | |||

| |align = right | |||

| |width = 34% | |||

| |fontsize = 85% | |||

| |bgcolor = AliceBlue | |||

| |style = | |||

| |title_bg = | |||

| |title_fnt = | |||

| |tstyle = text-align: left; | |||

| |qalign = right | |||

| |qstyle = text-align: left; | |||

| |quoted = yes | |||

| |salign = right | |||

| |sstyle = text-align: right; | |||

| }}A feature of all settler societies during the colonial period was the ability of European settlers to obtain for themselves a disproportionate share in landownership.<ref name="mosley2009_5">], p. </ref> Kenya was thus no exception, with the first white settlers arriving in 1902 as part of Governor ]'s plan to have a settler economy pay for the recently completed ].<ref name="anderson2005_3">], p. 3.</ref><ref name="elkins2005_2">], p. 2. Elkins notes that the (British taxpayer) loans were never repaid on the Uganda Railway; they were written off in the 1930s.</ref> The success of Eliot's planned settler economy would depend heavily on the availability of land, labour and capital,<ref name="kanogo1987_8">], p. </ref> and so, over the next three decades, the colonial government and settlers consolidated their control over Kenyan land, and 'encouraged' Africans to become wage labourers. | |||

| Until the mid-1930s, the two primary complaints were low native Kenyan wages and the requirement to carry an identity document, the '']''.{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=10}} From the early 1930s, however, two others began to come to prominence: effective and elected African-political-representation, and land.{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=10}} The British response to this clamour for ] came in the early 1930s when they set up the Carter Land Commission.<ref name="Carter 1934">{{Harvnb|Carter|1934}}.</ref> | |||

| Through a series of expropriations, the colony's government seized about {{convert|7000000|acre|km2 sqmi}} of land, some of it in the especially fertile hilly-regions of ] and ]s, areas later known as the White Highlands due to the exclusively-European farmland which existed there.<ref name="kanogo1987_8"/> "In particular," the British government's 1925 East Africa Commission noted, "the treatment of the Giriama tribe was very bad. This tribe was moved backwards and forwards so as to secure for the Crown areas which could be granted to Europeans."<ref name="eac1925_159">], p. 159.</ref> Coupled with an increasing African population, the land expropriation became an increasingly bitter point of contention. The Kikuyu, who lived in the ], ] and ] districts of Central Province, were the ethnic group most affected by the colonial government's land expropriation and European settlement;<ref name="elkins2005_12">], p. 12.</ref> by 1933, they had had over {{convert|109.5|sqmi|km2}} of their potentially highly valuable land alienated.<ref name="kanogo1987_9">], p. </ref> The Kikuyu did mount a legal challenge to the expropriation of their land, but a Kenya High Court decision of 1921 cemented its legality.<ref name="eac1925_29">], p. 29. "This judgment is now widely known to Africans in Kenya, and it has become clear to them that, without their being previously informed or consulted, their rights in their tribal land, whether communal or individual, have "disappeared" in law and have been superseded by the rights of the Crown."</ref> | |||

| The Commission reported in 1934, but its conclusions, recommendations and concessions to Kenyans were so conservative that any chance of a peaceful resolution to native Kenyan land-hunger was ended.<ref name="Coray 1978 p179" /> Through a series of ]s, the government seized about {{convert|7000000|acre|km2 sqmi}} of land, most of it in the fertile hilly regions of ] and ]s, later known as the ] due to the exclusively European-owned farmland there.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8" /> In Nyanza the Commission restricted 1,029,422 native Kenyans to {{convert|7114|sqmi|km2}}, while granting {{convert|16700|sqmi|km2}} to 17,000 Europeans.<ref name="Shilaro 2002 123">{{Harvnb|Shilaro|2002|p=}}.</ref> By the 1930s, and for the Kikuyu in particular, land had become the number one grievance concerning colonial rule,{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=10}} the situation so acute by 1948 that 1,250,000 Kikuyu had ownership of 2,000 square miles (5,200 km<sup>2</sup>), while 30,000 British settlers owned 12,000 square miles (31,000 km<sup>2</sup>), albeit most of it not on traditional Kikuyu land. "In particular", the British government's 1925 East Africa Commission noted, "the treatment of the ] was very bad. This tribe was moved backwards and forwards so as to secure for the Crown areas which could be granted to Europeans."<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p159">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=159}}.</ref> | |||

| As mentioned, the colonial government and White farmers also wanted cheap labour<ref name="anderson2004_498">], p. "The recruitment of African labor at poor rates of pay and under primitive conditions of work was characteristic of the operation of colonial capitalism in Africa during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. . . . olonial states readily colluded with capital in providing the legal framework necessary for the recruitment and maintenance of labor in adequate numbers and at low cost to the employer. . . . The colonial state shared the desire of the European settler to encourage Africans into the labour market, whilst also sharing a concern to moderate the wages paid to workers".</ref> which, for a period, the government acquired from Africans through force.<ref name="kanogo1987_9"/><ref>A common view among settlers was that "A good sound system of compulsory labour would do more to raise the nigger in five years than all the millions that have been sunk in missionary efforts for the last fifty." (The quote is of a settler called Major Grogan). {{cite web |url=http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1927/dec/07/east-african-policy#column_572 |title=EAST AFRICAN POLICY. House of Lords debate, Hansard vol 69 cc 551–600 |author=Lord Sydney Olivier |date=7 December 1927 |authorlink=Sydney Olivier, 1st Baron Olivier}}</ref> Confiscating land from Africans itself helped to create a pool of ]ers, but the colony introduced measures that forced more Africans to submit to wage labour: the introduction of the Hut and Poll Taxes (1901 and 1910 respectively);<ref name="kanogo1987_9"/><ref name="eac1925_173">], p. 173. "Casual labourers leave their reserves . . . to earn the wherewithal to pay their "Hut Tax" and to get money to purchase a few luxuries."</ref> the establishment of reserves for each ethnic group, serving to isolate each ethnic group and exacerbate overcrowding;<ref>], p. "African reserves in Kenya were legally constituted in the Crown Lands Amendment Ordinance of 1926". Though finalised in 1926, reserves were first instituted by the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1915—see ], p. 29.</ref> the discouragement of African's growing cash crops;<ref name="kanogo1987_9"/> the Masters and Servants Ordinance (1906) and an identification pass known as the ''kipande'' (1918) to control the movement of labour and to curb desertion;<ref name="kanogo1987_9"/><ref name="anderson2004_506">], pp. </ref> and the exemption of wage labourers from forced labour and other compulsory, detested tasks such as conscription.<ref name="kanogo1987_13">], p. </ref><ref name="anderson2004_505">], pp. </ref> | |||

| The Kikuyu, who lived in the ], ] and ] areas of what became Central Province, were one of the ethnic groups most affected by the colonial government's land expropriation and European settlement;<ref name="Edgerton 1989 5">{{Harvnb|Edgerton|1989|p=5}}.</ref> by 1933, they had had over {{convert|109.5|sqmi|km2}} of their potentially highly valuable land alienated.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1993|p=}}.</ref> The Kikuyu mounted a legal challenge against the expropriation of their land, but a Kenya High Court decision of 1921 reaffirmed its legality.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p29">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=29}}: "This judgment is now widely known to Africans in Kenya, and it has become clear to them that, without their being previously informed or consulted, their rights in their tribal land, whether communal or individual, have 'disappeared' in law and have been superseded by the rights of the Crown."</ref> In terms of lost acreage, the ] and ] were the biggest losers of land.<ref name="Welch 1980 p16">{{Harvnb|Emerson Welch|1980|p=}}.</ref> | |||

| African labourers were in one of three categories: ''squatter'', ''contract'', or ''casual''.{{ref label|Note3|C|C}} By the end of WWI, squatters had become well established on European farms and plantations in Kenya, with Kikuyu squatters comprising the majority of agricultural workers on settler plantations.<ref name="kanogo1987_8"/> An unintended consequence of colonial rule,<ref name="kanogo1987_8"/> the squatters were targeted from 1918 onwards by a series of Resident Native Labourers Ordinances—criticised by at least some ]<ref>House of Commons Debate, 10 November 1937. Vol. 328, cc. . "Mr. Creech Jones asked the Secretary of State for the Colonies whether he will withhold his consent from the Native Tenants Land Ordinance in Kenya on the ground of the heavy penalties imposed on Africans for breach of contract, the decreased security given to the natives, the increased period of compulsory labour, and other reactionary amendments to the previous Ordinance".</ref>—which progressively curtailed squatter rights and subordinated African farming to that of the settlers.<ref name="elkins2005_17">], p. 17.</ref> The Ordinance of 1939 finally eliminated squatters' remaining tenancy rights, and permitted settlers to demand 270 days' labour from any squatters on their land.<ref name="anderson2004_508">], p. </ref> and, after WWII, the situation for squatters deteriorated rapidly, a situation the squatters resisted fiercely.<ref name="Kanogo1987_96-97">], p. </ref> | |||

| The colonial government and white farmers also wanted cheap labour<ref name="Anderson 2004 p498">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|p=}}. "The recruitment of African labor at poor rates of pay and under primitive conditions of work was characteristic of the operation of colonial capitalism in Africa during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. ... olonial states readily colluded with capital in providing the legal framework necessary for the recruitment and maintenance of labor in adequate numbers and at low cost to the employer. ... The colonial state shared the desire of the European settler to encourage Africans into the labour market, whilst also sharing a concern to moderate the wages paid to workers".</ref> which, for a period, the government acquired from native Kenyans through force.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9"/> Confiscating the land itself helped to create a pool of wage labourers, but the colony introduced measures that forced more native Kenyans to submit to wage labour: the introduction of the Hut and Poll Taxes (1901 and 1910 respectively);<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9"/><ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p173">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=173}}: "Casual labourers leave their reserves ... to earn the wherewithal to pay their 'Hut Tax' and to get money to purchase trade goods."</ref> the establishment of reserves for each ethnic group,<ref>{{Harvnb|Shilaro|2002|p=}}: "African reserves in Kenya were legally constituted in the Crown Lands Amendment Ordinance of 1926".</ref>{{efn|Though finalised in 1926, reserves were first instituted by the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1915.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p29"/>}} which isolated ethnic groups and often exacerbated overcrowding;{{citation needed|date=October 2023}} the discouragement of native Kenyans' growing ]s;<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9"/> the ] (1906) and an identification pass known as the ''kipande'' (1918) to control the movement of labour and to curb desertion;<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9"/><ref name="Anderson 2004 p506">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|pp=}}.</ref> and the exemption of wage labourers from forced labour and other detested obligations such as conscription.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 13">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1993|p=}}.</ref><ref name="Anderson 2004 p505">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|pp=}}.</ref> | |||

| In the early 1920s, though, despite the presence of 100,000 squatters and tens of thousands more wage labourers,<ref name="anderson2004_507">], p. </ref> there was still not enough African labour available to satisfy the settlers' needs.<ref name="eac1925_166">], p. 166. "In many parts of the territory we were informed that the majority of farmers were having the utmost difficulty in obtaining labour to cultivate and to harvest their crops".</ref> The colonial government duly tightened the measures to force yet more Kenyans to become low-paid wage-labourers on settler farms. | |||

| === Native labourer categories === | |||

| The colonial government used the measures brought in as part of its land expropriation and labour 'encouragement' efforts to craft the third plank of its growth strategy for its settler economy: subordinating African farming to that of the Europeans.<ref name="kanogo1987_9"/> Nairobi also assisted the settlers with rail and road networks, subsidies on freight charges, agricultural and veterinary services, and credit and loan facilities.<ref name="kanogo1987_8"/> The near-total neglect of African farming during the first two decades of European settlement was noted by the East Africa Commission.<ref name="eac1925_155-156">], p. 155–6.</ref> | |||

| Native Kenyan labourers were of three categories: ''squatter'', ''contract'', or ''casual''.{{efn|"Squatter or resident labourers are those who reside with their families on European farms usually for the purpose of work for the owners. ... Contract labourers are those who sign a contract of service before a magistrate, for periods varying from three to twelve months. Casual labourers leave their reserves to engage themselves to European employers for any period from one day upwards."<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p173"/> In return for his services, a squatter was entitled to use some of the settler's land for cultivation and grazing.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 10">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1993|p=}}.</ref> Contract and casual workers are together referred to as ''migratory'' labourers, in distinction to the permanent presence of the squatters on farms. The phenomenon of squatters arose in response to the complementary difficulties of Europeans in finding labourers and of Africans in gaining access to arable and grazing land.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8"/>}} By the end of World War I, squatters had become well established on European farms and plantations in Kenya, with Kikuyu squatters constituting the majority of agricultural workers on ].<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8"/> An unintended consequence of colonial rule,<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8"/> the squatters were targeted from 1918 onwards by a series of Resident Native Labourers Ordinances—criticised by at least some ]<ref>{{Cite web |last= Creech Jones |first= Arthur |author-link= Arthur Creech Jones |title= Native Labour; House of Commons Debate, 10 November 1937 |url= https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1937/nov/10/native-labour |work= ] |series= Series 5, Vol. 328, cc. 1757-9 |date= 10 November 1937 |access-date= 13 April 2013 |archive-date= 15 December 2018 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20181215221829/https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1937/nov/10/native-labour |url-status= live }}</ref>—which progressively curtailed squatter rights and subordinated native Kenyan farming to that of the settlers.<ref name="Elkins 2005 p17">{{Harvnb|Elkins|2005|p=17}}.</ref> The Ordinance of 1939 finally eliminated squatters' remaining tenancy rights, and permitted settlers to demand 270 days' labour from any squatters on their land.<ref name="Anderson 2004 p508">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|p=}}.</ref> and, after World War II, the situation for squatters deteriorated rapidly, a situation the squatters resisted fiercely.<ref name="Kanogo1987_96-97">{{Harvnb|Kanogo|1993|pp=}}.</ref> | |||

| In the early 1920s, though, despite the presence of 100,000 squatters and tens of thousands more wage labourers,<ref name="Anderson 2004 p507">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|p=}}.</ref> there was still not enough native Kenyan labour available to satisfy the settlers' needs.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p166">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=166}}: "In many parts of the territory we were informed that the majority of farmers were having the utmost difficulty in obtaining labour to cultivate and to harvest their crops".</ref> The colonial government duly tightened the measures to force more Kenyans to become low-paid wage-labourers on settler farms.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.kenyaembassydc.org/aboutkenyahistory.html|title=History|publisher=kenyaembassydc.org|access-date=13 May 2019|archive-date=22 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190522124317/http://kenyaembassydc.org/aboutkenyahistory.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The hatred toward colonial rule was hardly stemmed by the wanting provision of medical services for Africans,<ref name="eac1925_180">], p. 180. "The population of the district to which one medical officer is allotted amounts more often than not to over a quarter of a million natives distributed over a large area. . . . here are large areas in which no medical work is being undertaken."</ref> nor by the fact that in 1923, for example, "the maximum amount that could be considered to have been spent on services provided exclusively for the benefit of the native population was slightly over one-quarter of the taxes paid by them".<ref name ="eac1925_187">], p. 187.</ref> The tax burden on Europeans in the early 1920s, meanwhile, was "absurdly" light.<ref name="eac1925_187"/><!--blah blah blah<ref name="Swainson1980_23">, p. </ref>--> | |||

| The colonial government used the measures brought in as part of its land expropriation and labour 'encouragement' efforts to craft the third plank of its growth strategy for its settler economy: subordinating African farming to that of the Europeans.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 9"/> Nairobi also assisted the settlers with rail and road networks, subsidies on freight charges, agricultural and veterinary services, and credit and loan facilities.<ref name="Kanogo 1993 8"/> The near-total neglect of native farming during the first two decades of European settlement was noted by the East Africa Commission.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p155-156">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|pp=155–156}}.</ref> | |||

| Kenyan employees were often appallingly treated by their European employers—sometimes even beaten to death by them—with some settlers arguing that Africans "were as children and should be treated as such". Amongst other offences, it was widely acknowledged that few settlers hesitated to flog their servants for petty offences. To make matters even worse, African workers were poorly served by colonial labour-legislation and a prejudiced legal-system. The vast majority of Kenyan employees' violations of labour legislation were settled with "rough justice" meted out by their employers. Most colonial magistrates appear to have been unconcerned by the illegal practice of settler-administered flogging; indeed, during the 1920s, flogging was the magisterial punishment-of-choice for African convicts. The principle of punitive sanctions against workers was not removed from the Kenyan labour statutes until the 1950s.<ref name="anderson2004_516-526">], pp. </ref> | |||

| The resentment of colonial rule would not have been decreased by the wanting provision of medical services for native Kenyans,<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p180">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=180}}: "The population of the district to which one medical officer is allotted amounts more often than not to over a quarter of a million natives distributed over a large area. ... here are large areas in which no medical work is being undertaken."</ref> nor by the fact that in 1923, for example, "the maximum amount that could be considered to have been spent on services provided exclusively for the benefit of the native population was slightly over one-quarter of the taxes paid by them".<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p187">{{Harvnb|Ormsby-Gore, ''et al.''|1925|p=187}}.</ref> The tax burden on Europeans in the early 1920s, meanwhile, was very light relative to their income.<ref name="Ormsby-Gore 1925 p187"/> Interwar infrastructure-development was also largely paid for by the indigenous population.<ref name="Swainson 1980 p23">{{Harvnb|Swainson|1980|p=}}.</ref> | |||

| Kenyan employees were often poorly treated by their European employers, with some settlers arguing that native Kenyans "were as children and should be treated as such". Some settlers flogged their servants for petty offences. To make matters even worse, native Kenyan workers were poorly served by colonial labour-legislation and a prejudiced legal-system. The vast majority of Kenyan employees' violations of labour legislation were settled with "rough justice" meted out by their employers. Most colonial magistrates appear to have been unconcerned by the illegal practice of settler-administered flogging; indeed, during the 1920s, flogging was the magisterial punishment-of-choice for native Kenyan convicts. The principle of punitive sanctions against workers was not removed from the Kenyan labour statutes until the 1950s.<ref name="Anderson 2004 pp507-526">{{Harvnb|Anderson|2004|pp=}}.</ref> | |||

| {{Quote box | {{Quote box | ||

| |quote = The greater part of the wealth of the country is at present in our hands. |

|quote = The greater part of the wealth of the country is at present in our hands. ... This land we have made is our land by right—by right of achievement.{{sfn|Curtis|2003|pp=320–321}} | ||

| |source = —Speech by Deputy Colonial Governor<br>30 November 1946 | |source = —Speech by Deputy Colonial Governor<br />30 November 1946 | ||

| |align = |

|align = right | ||

| |width = 33% | |width = 33% | ||

| |fontsize = 85% | |fontsize = 85% | ||

| Line 164: | Line 110: | ||

| |salign = right | |salign = right | ||

| |sstyle = text-align: right; | |sstyle = text-align: right; | ||

| }} | |||

| }}Until the mid-1930s, the two primary complaints were low African wages and the ''kipande''.<ref name="anderson2005_10"/> From the early 1930s, however, two others began to come to prominence: effective and elected African-political-representation, and land.<ref name="anderson2005_10"/> The British response to this clamour for ] came in the early 1930s when they set up the Carter Land Commission.<ref name="Carter1934">].</ref> The Commission reported in 1934, but its conclusions, recommendations and concessions to Kenyans were so conservative that any chance of a peaceful resolution to African land-hunger was ended.<ref name="coray1978"/><ref name="anderson2005_22a">], p. 22. "The Land Commission report of 1934 was the stone upon which moderate African politics was broken. . . . Militant nationalism was conceived in Kikuyu reaction to the report of the Kenya Land Commission. . . . Opposition to the Land Commission's findings fed militancy all the more over the next twenty years as the pressures upon land within the Kikuyu reserve became greater and the settler stranglehold on the political economy of the colony tightened".</ref> In Nyanza, for example, the Commission restricted 1,029,422 Africans to {{convert|7114|sqmi|km2}}, while granting {{convert|16700|sqmi|km2}} to 17,000 Europeans.<ref>], p. </ref> By the 1930s, and for the Kikuyu in particular, land had become the number one grievance concerning colonial rule,<ref name="anderson2005_10"/> the situation so acute by 1948 that 1,250,000 Kikuyu had ownership of 2,000 square miles (5,200 km²), while 30,000 British settlers owned 12,000 square miles (31,000 km²). | |||

| As a result of the situation in the highlands, thousands of Kikuyu migrated into cities in search of work, contributing to the doubling of ]'s population between 1938 and 1952.{{ |

As a result of the situation in the highlands and growing job opportunities in the cities, thousands of Kikuyu migrated into cities in search of work, contributing to the doubling of ]'s population between 1938 and 1952.<ref>{{cite book|author1= R. M. A. Van Zwanenberg|author2=Anne King|title=An Economic History of Kenya and Uganda 1800–1970|date=1975|publisher=The Bowering Press|isbn=978-0-333-17671-9}}</ref> At the same time, there was a small, but growing, class of Kikuyu landowners who consolidated Kikuyu landholdings and forged ties with the colonial administration, leading to an economic rift within the Kikuyu. | ||

| ==Mau Mau warfare== | |||

| Around 1943, residents of Olenguruone radicalised the traditional Kikuyu practice of oathing, and extended oathing to women and children.<ref name="elkins2005_25">], p. 25.</ref> | |||

| Mau Mau were the militant wing of a growing clamour for political representation and freedom in Kenya. The first attempt to form a countrywide political party began on 1 October 1944.<ref name="Ogot 2003 16">{{Harvnb|Ogot|2003|p=}}.</ref> This fledgling organisation was called the Kenya African Study Union. ] was the first chairman, but he soon resigned. There is dispute over Thuku's reason for leaving KASU: Bethwell Ogot says Thuku "found the responsibility too heavy";<ref name="Ogot 2003 16" /> David Anderson states that "he walked out in disgust" as the militant section of KASU took the initiative.{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=282}} KASU changed its name to the ] (KAU) in 1946. Author Wangari Maathai writes that many of the organizers were ex-soldiers who fought for the British in Ceylon, Somalia, and Burma during the Second World War. When they returned to Kenya, they were never paid and did not receive recognition for their service, whereas their British counterparts were awarded medals and received land, sometimes from the Kenyan veterans.<ref>{{cite book|title=Unbowed: a memoir|author=Wangari Maathai|pages=61–63|publisher=Alfred A. Knopf|date=2006|isbn=0307263487}}</ref> | |||

| The failure of KAU to attain any significant reforms or redress of grievances from the colonial authorities shifted the political initiative to younger and more militant figures within the native Kenyan trade union movement, among the squatters on the settler estates in the Rift Valley and in KAU branches in Nairobi and the Kikuyu districts of central province.<ref name="Berman 1991 p198">{{Harvnb|Berman|1991|p=198}}.</ref> Around 1943, residents of Olenguruone Settlement radicalised the traditional practice of ], and extended oathing to women and children.<ref name="Elkins 2005 p25">{{Harvnb|Elkins|2005|p=25}}.</ref> By the mid-1950s, 90% of Kikuyu, Embu and Meru were oathed.<ref name="Branch 2007 p1">{{Harvnb|Branch|2007|p=1}}.</ref> On 3 October 1952, Mau Mau claimed their first European victim when they stabbed a woman to death near her home in Thika.<ref name="Elkins 2005 32" /> Six days later, on 9 October, Senior Chief Waruhiu was shot dead in broad daylight in his car,<ref name="Edgerton 1989 65">{{Harvnb|Edgerton|1989|p=65}}.</ref> which was an important blow against the colonial government.<ref name="Füredi 1989 116">{{Harvnb|Füredi|1989|p=}}.</ref> Waruhiu had been one of the strongest supporters of the British presence in Kenya. His assassination gave ] the final impetus to request permission from the Colonial Office to declare a State of Emergency.<ref name="Edgerton 1989 66_67">{{Harvnb|Edgerton|1989|pp=66–67}}.</ref> | |||

| ===African politics=== | |||

| The first attempt to form a countrywide political party occurred on 1 October 1944.<ref name="ogot2003_16">], p. </ref> This fledgling organisation was called the Kenya African Study Union (so named to mask its anti-colonial politics); its inaugural chairman was Harry Thuku, who soon resigned his chairmanship.<ref name="ogot2003_16"/> There is dispute over Thuku's reason for leaving KASU: Bethwell Ogot states that Thuku "found the responsibility too heavy";<ref name="ogot2003_16"/> David Anderson states that "he walked out in disgust" as the militant section of KASU took the initiative.<ref name="anderson2005_282">], p. 282.</ref> KASU changed its name to the KAU in 1946.<!--the symbolic origin of the beginning of Mau Mau. The colonial government briefly considered promulgating racial equality laws, but ultimately chose to maintain the racist status quo. This final failure of the KAU to achieve political reform soon led to splits within the KAU. | |||

| This | |||

| The Kikuyu Central Association was banned in 1940, but in 1944 KASU was formed.--> | |||

| The Mau Mau attacks were mostly well organised and planned. | |||

| By the late 1940s the Kikuyu were a deeply divided people, increasingly in conflict among themselves as well as with the colonial political and economic order.<ref name="berman1991_198">], p. 198.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|...the insurgents' lack of heavy weaponry and the heavily entrenched police and Home Guard positions meant that Mau Mau attacks were restricted to nighttime and where loyalist positions were weak. When attacks did commence they were fast and brutal, as insurgents were easily able to identify loyalists because they were often local to those communities themselves. The ] was by comparison rather outstanding and in contrast to regular Mau Mau strikes which more often than not targeted only loyalists without such massive civilian casualties. "Even the attack upon Lari, in the view of the rebel commanders was strategic and specific."{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=252}}}} | |||

| The failure of the KAU to attain any significant reforms or redress of grievances from the colonial authorities shifted the political initiative to younger and more militant figures within the African trade union movement, among the squatters on the settler estates in the Rift Valley and in KAU branches in Nairobi and the Kikuyu districts of central province.<ref name="berman1991_198"/> | |||

| The Mau Mau command, contrary to the Home Guard who were stigmatised as "the running dogs of British Imperialism",{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=239}} were relatively well educated. General Gatunga had previously been a respected and well-read Christian teacher in his local Kikuyu community. He was known to meticulously record his attacks in a series of five notebooks, which when executed were often swift and strategic, targeting loyalist community leaders he had previously known as a teacher.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Mau Mau Rebellion|last=Van der Bijl|first=Nicholas|publisher=Pen and Sword|year=2017|isbn=978-1473864603|pages=151|oclc=988759275}}</ref> | |||

| The Mau Mau military strategy was mainly guerrilla attacks launched under the cover of darkness. They used improvised and stolen weapons such as guns,<ref> August 28, 2024. ]</ref> as well as weapons such as machetes and bows and arrows in their attacks.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1963-09-6-4|title=Mau Mau reed shafted arrows with some barbed 'wire' iron arrow heads and bound nocks, Kenya, 1953|publisher=] |archiveurl=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20230716000753/https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1963-09-6-4|archive-date=16 July 2023|access-date=16 July 2023|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite thesis|type=MA|last=Stoddard |first=James |date=2020|title=Mau Mau Blasters: The Homemade Guns of the Mau Mau Uprising|publisher=University of Central Florida |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20221112195601/https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1137&context=etd2020|archive-date=November 12, 2022 |url=https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1137&context=etd2020}}</ref> They maimed cattle and, in one case, poisoned a herd.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://owaahh.com/when-the-mau-mau-used-a-biological-weapon/|title=When the Mau Mau Used a Biological Weapon |date=30 October 2014|work=Owaahh |access-date=12 February 2018|language=en-US |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20230410145343/http://owaahh.com/when-the-mau-mau-used-a-biological-weapon/|archive-date=April 10, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| In addition to physical warfare, the Mau Mau rebellion also generated a propaganda war, where both the British and Mau Mau fighters battled for the hearts and minds of Kenya's population. Mau Mau propaganda represented the apex of an 'information war' that had been fought since 1945, between colonial information staff and African intellectuals and newspaper editors.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal |last=Osborne |first=Myles |title='The Rooting Out of Mau Mau from the Minds of the Kikuyu is a Formidable Task': Propaganda and the Mau Mau War |date=2015-01-30 |journal=The Journal of African History |volume=56 |issue=1 |pages=77–97 |doi=10.1017/s002185371400067x |s2cid=159690162 |issn=0021-8537|doi-access=free }}</ref> The Mau Mau had learned much from - and built upon - the experience and advice of newspaper editors since 1945. In some cases, the editors of various publications in the colony were directly involved in producing Mau Mau propaganda. British Officials struggled to compete with the 'hybrid, porous, and responsive character' during the rebellion, and faced the same challenges in responding to Mau Mau propaganda, particularly in instances where the Mau Mau would use creative ways such as hymns to win and maintain followers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Leakey |first=L.S.B. |date=1954 |title=The religious element in Mau Mau |journal=African Music: Journal of the African Music Society |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=78–79 |doi=10.21504/amj.v1i1.235}}</ref> This was far more effective than government newspapers; however, once colonial officials brought the insurgency under control by late 1954, information officials gained an uncontested arena through which they won the propaganda war.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| Women formed a core part of the Mau Mau, especially in maintaining supply lines. Initially able to avoid the suspicion, they moved through colonial spaces and between Mau Mau hideouts and strongholds, to deliver vital supplies and services to guerrilla fighters including food, ammunition, medical care, and of course, information. Women such as ], exemplified this key role.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Kikuyu Women, the Mau Mau Rebellion and Social Change in Kenya|last = Presley|first = Cora Ann|publisher = Westview Press|year = 1992|location = Boulder}}</ref> An unknown number also fought in the war, with the most high-ranking being ]. | |||

| ==British reaction== | |||

| The British and international view was that Mau Mau was a savage, violent, and depraved tribal cult, an expression of unrestrained emotion rather than reason. Mau Mau was "perverted tribalism" that sought to take the Kikuyu people back to "the bad old days" before British rule.<ref name="Füredi 1989 4">{{Harvnb|Füredi|1989|p=}}.</ref><ref name="Berman 1991 pp182-183">{{Harvnb|Berman|1991|pp=182–183}}.</ref> The official British explanation of the revolt did not include the insights of agrarian and agricultural experts, of economists and historians, or even of Europeans who had spent a long period living amongst the Kikuyu such as ]. Not for the first time,<ref name="Mahone 2006">{{Harvnb|Mahone|2006|p=241}}: "This article opens with a retelling of colonial accounts of the 'mania of 1911', which took place in the Kamba region of Kenya Colony. The story of this 'psychic epidemic' and others like it were recounted over the years as evidence depicting the predisposition of Africans to episodic mass hysteria."</ref> the British instead relied on the purported insights of the ethnopsychiatrist; with Mau Mau, it fell to John Colin Carothers to perform the desired analysis. This ethnopsychiatric analysis guided British psychological warfare, which painted Mau Mau as "an irrational force of evil, dominated by bestial impulses and influenced by world communism", and the later official study of the uprising, the Corfield Report.<ref name="McCulloch 2006 64to76">{{Harvnb|McCulloch|2006|pp=}}.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Carothers |first=J. C. |date=July 1947 |title=A Study of Mental Derangement in Africans, and an Attempt to Explain its Peculiarities, More Especially in Relation to the African Attitude to Life |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-mental-science/article/abs/study-of-mental-derangement-in-africans-and-an-attempt-to-explain-its-peculiarities-more-especially-in-relation-to-the-african-attitude-to-life/1E5DB8896931A8255D8A3DC7DA13BD26 |journal=Journal of Mental Science |language=en |volume=93 |issue=392 |pages=548–597 |doi=10.1192/bjp.93.392.548 |pmid=20273401 |issn=0368-315X |access-date=27 October 2023 |archive-date=27 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231027013000/https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-mental-science/article/abs/study-of-mental-derangement-in-africans-and-an-attempt-to-explain-its-peculiarities-more-especially-in-relation-to-the-african-attitude-to-life/1E5DB8896931A8255D8A3DC7DA13BD26 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The psychological war became of critical importance to military and civilian leaders who tried to "emphasise that there was in effect a civil war, and that the struggle was not black versus white", attempting to isolate Mau Mau from the Kikuyu, and the Kikuyu from the rest of the colony's population and the world outside. In driving a wedge between Mau Mau and the Kikuyu generally, these propaganda efforts essentially played no role, though they could apparently claim an important contribution to the isolation of Mau Mau from the non-Kikuyu sections of the population.<ref name="Füredi 1994 119to121">{{Harvnb|Füredi|1994|pp=}}.</ref> | |||

| By the mid-1960s, the view of Mau Mau as simply irrational activists was being challenged by memoirs of former members and leaders that portrayed Mau Mau as an essential, if radical, component of African nationalism in Kenya and by academic studies that analysed the movement as a modern and nationalist response to the unfairness and oppression of colonial domination.<ref name="Berman 1991 pp183-185">{{Harvnb|Berman|1991|pp=183–185}}.</ref> | |||

| There continues to be vigorous debate within Kenyan society and among the academic community within and outside Kenya regarding the nature of Mau Mau and its aims, as well as the response to and effects of the uprising.<ref name="Clough 1998 p4">{{Harvnb|Clough|1998|p=}}.</ref><ref name="Branch 2009 p3">{{Harvnb|Branch|2009|p=}}.</ref> Nevertheless, partly because as many Kikuyu fought against Mau Mau on the side of the colonial government as joined them in rebellion,<ref name="Branch 2009 pxii"/> the conflict is now often regarded in academic circles as an intra-Kikuyu civil war,<ref name="Branch 2009 p3"/><ref>{{Harvnb|Anderson|2005|p=4}}: "Much of the struggle tore through the African communities themselves, an internecine war waged between rebels and so-called 'loyalists' – Africans who took the side of the government and opposed Mau Mau."</ref> a characterisation that remains extremely unpopular in Kenya. In August 1952, Kenyatta told a Kikuyu audience "Mau Mau has spoiled the country...Let Mau Mau perish forever. All people should search for Mau Mau and kill it".<ref>John Reader, ''Africa: A Biography of the Continent'' (1997), p. 641.</ref><ref name="bbc_07042011"/> | |||

| Kenyatta described the conflict in his memoirs as a ] rather than a rebellion.<ref>{{cite journal |jstor=40402312|title=Revolt and Repression in Kenya: The "Mau Mau" Rebellion, 1952–1960 |last1=Newsinger|first1=John |journal=Science & Society|year=1981|volume=45 |issue=2|pages=159–185}}</ref> One reason that the revolt was largely limited to the Kikuyu people was, in part, that they had suffered the most as a result of the negative aspects of British colonialism.<ref name="Füredi 1989 4to5">{{Harvnb|Füredi|1989|pp=}}: "Since they were the most affected by the colonial system and the most educated about its ways, the Kikuyu emerged as the most politicized African community in Kenya."</ref><ref name="Berman 1991 p196">{{Harvnb|Berman|1991|p=196}}: "The impact of colonial capitalism and the colonial state hit the Kikuyu with greater force and effect than any other of Kenya's peoples, setting off new processes of differentiation and class formation."</ref> | |||

| Wunyabari O. Maloba regards the rise of the Mau Mau movement as "without doubt, one of the most important events in recent African history".<ref name="thomas1993">{{cite journal |last=Thomas |first=Beth |year=1993 |url=http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/36/index-ba.html |page=7 |title=Historian, Kenya native's book on Mau Mau revolt |journal=UpDate |volume=13 |issue=13 |access-date=28 May 2010 |archive-date=25 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225224617/http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/36/index-ba.html |url-status=live }}</ref> David Anderson, however, considers Maloba's and similar work to be the product of "swallowing too readily the propaganda of the Mau Mau war", noting the similarity between such analysis and the "simplistic" earlier studies of Mau Mau.{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=10}} This earlier work cast the Mau Mau war in strictly bipolar terms, "as conflicts between anti-colonial nationalists and colonial collaborators".{{sfn|Anderson|2005|p=10}} ]' 2005 study, '']'', awarded the 2006 ],<ref Name="Pulitzer">{{cite web |title=Pulitzer Prize Winners: General Nonfiction |publisher=pulitzer.org |url=http://www.pulitzer.org/ |access-date=2008-03-16 |archive-date=24 February 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080224184433/http://www.pulitzer.org/ |url-status=live }}</ref> was also controversial in that she was accused of presenting an equally binary portrayal of the conflict<ref name="Ogot 2005 502">{{Harvnb|Ogot|2005|p=502}}: "There was no reason and no restraint on both sides, although Elkins sees no atrocities on the part of Mau Mau."</ref> and of drawing questionable conclusions from limited census data, in particular her assertion that the victims of British punitive measures against the Kikuyu amounted to as many as 300,000 dead.<ref name="elstein">See in particular ]'s angry letters: | |||

| * {{cite journal |title=Letters: Tell me where I'm wrong |journal=London Review of Books |volume=27 |issue=11 |url=http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n11/letters |year=2005 |access-date=3 May 2011 |archive-date=3 October 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191003091349/https://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n11/letters |url-status=live }} | |||