| Revision as of 14:34, 2 October 2009 editDojarca (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers5,831 edits It is noyt picture, it is link to another article, so it should be named as the article. Also restored the deleted link to the source← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:08, 13 December 2024 edit undo120.19.134.59 (talk) serial comma; article uses it elsewhere, e.g. "German forces invaded Poland from the west, north, and south on 1 September 1939" | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{short description|1939 invasion of the Second Polish Republic by the Soviet Union during World War II}} | ||

| {{About| part of the ] in 1939|the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1920|Polish–Soviet War}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| {{infobox military conflict | |||

| | conflict = Soviet invasion of Poland | |||

| | partof = the ] in ] | |||

| | image = Lviv 1939 Sov Cavalry.jpg | |||

| | image_size = 290 | |||

| | caption = Soviet parade in ], September 1939, following the city's surrender | |||

| | date = 17 September – 6 October 1939 | |||

| | place = ] | |||

| | coordinates = | |||

| | map_type = | |||

| | latitude = | |||

| | longitude = | |||

| | map_size = | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| | map_label = | |||

| | territory = Territory of ] annexed by the ] | |||

| | result = Soviet victory | |||

| | status = | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flagcountry|Second Polish Republic|1928}} | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flag|Soviet Union|1936}}<br>'''Co-belligerent:'''<br>{{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| | commander1 = {{flag icon|Second Polish Republic|1928}} ] | |||

| | commander2 = {{flag icon|Soviet Union|1936}} ]<br>{{flag icon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| | units1 = | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| | units2 = | |||

| |conflict=Soviet invasion of Poland | |||

| | units3 = | |||

| |partof=the ] in ] | |||

| | strength1 = 20,000 ]<ref name="Sanford 20-24" />{{#tag:ref|Increasing numbers of ] units, as well as Polish Army units stationed in the East during peacetime, were sent to the Polish-German border before or during the German invasion. The Border Protection Corps forces guarding the eastern border numbered approximately 20,000 men.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" />|group="Note"}}<br />450,000 ]<ref name="PWN_KW_old" />{{#tag:ref|The retreat from the Germans disrupted and weakened Polish Army units, making estimates of their strength problematic. Sanford estimated that approximately 450,000 troops found themselves in the line of the Soviet advance and offered only sporadic resistance.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" />|group="Note"}} | |||

| |image=] | |||

| | strength2 = 600,000–800,000 troops<ref name="PWN_KW_old" /><ref name="Krivosheev" /><br />33+ divisions<br />11+ brigades<br />4,959 guns<br />4,736 tanks<br />3,300 aircraft | |||

| |place=] | |||

| | strength3 = | |||

| |result=Soviet victory | |||

| | casualties1 = '''Total:''' ~343,000–477,000<hr>3,000–7,000 killed or missing<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Wojsko92" /><br />Up to 20,000 wounded<ref name="Sanford 20-24" />{{#tag:ref|The figures do not take into account the approximately 2,500 prisoners of war executed in immediate reprisals or by anti-Polish ].<ref name="Sanford 20-24" />|group="Note"}}<br />320,000–450,000 captured<ref name=Zaloga>{{cite book|author=Steve Zaloga|title=Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IXshAQAAIAAJ|year=2004|publisher=Praeger|isbn=978-0-275-98278-2}}</ref>{{rp|85}} | |||

| |combatant1=] ] | |||

| | casualties2 = '''Total:''' 3,858–13,000<hr>1,475–3,000 killed or missing<br />2,383–10,000 wounded{{#tag:ref|Soviet official losses – figures provided by Krivosheev – are currently estimated at 1,475 KIA or MIA presumed dead (Ukrainian Front – 972, Belorussian Front – 503), and 2,383 WIA (Ukrainian Front – 1,741, Belorussian Front – 642). The Soviets lost approximately 150 tanks in combat of which 43 as irrecoverable losses, while hundreds more suffered technical failures.<ref name="Krivosheev" /> Sanford indicates that Polish estimates of Soviet losses are 3,000 dead and 10,000 wounded.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> Russian historian Igor Bunich estimates Soviet losses at 5,327 KIA or MIA without a trace and WIA.<ref name="WIF" />|group="Note"}} | |||

| |combatant2=] ] | |||

| | casualties3 = | |||

| |commander1=] ] | |||

| | notes = | |||

| |commander2=] ] <small>(]),</small><br />] ] <small>(])</small> | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Soviet invasion of Poland}}{{Campaignbox Polish September Campaign}}{{Polish-Russian Wars}} | |||

| |strength1=Over 20,000{{Ref_label|a|a|none}}<br />20 understrength battalions of ]<ref name="Wojsko"/> and improvised parts of the ].<ref name="PWN_KW_old"/> | |||

| }} | |||

| |strength2=Estimates vary from 466,516<ref>Colonel-General ], ''Soviet casualties and combat losses in the twentieth century''.</ref> to over 800,000<ref name="PWN_KW_old">{{pl icon}} (September Campaign 1939) from ]. ], mid-2006. Retrieved 16 July 2007.</ref><br />33+ divisions,<br />11+ brigades | |||

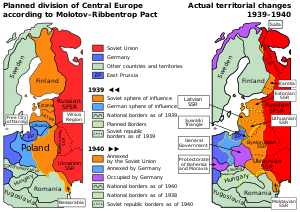

| The '''Soviet invasion of Poland''' was a ] by the ] without a formal ]. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded ] from the east, 16 days after ] ] from the west. Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the ] by ] and the ].<ref name="Gross 17-18" /> This division is sometimes called the ]. The Soviet (as well as German) invasion of Poland was indirectly indicated in the "secret protocol" of the ] signed on 23 August 1939, which divided Poland into "]" of the two powers.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1939pact.asp |title= The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, 1939 |date=26 January 1996 |publisher= Fordham University |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> German and Soviet cooperation in the invasion of Poland has been described as ].<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> | |||

| |casualties1=Estimates range from 3,000 dead and 20,000 wounded<ref name="Sanford"/> to about 7,000 dead or missing,<ref name="Wojsko"/><br />not counting about 2,500 POWs executed in immediate reprisals or by anti-Polish ] bands.<ref name="Sanford"/><br />250,000<ref name="Wojsko"/> | |||

| |casualties2=Estimates range from 737 dead and under 1,862 total casualties (Soviet estimates)<ref name="Sanford"/><ref name="Gross">Gross, p. 17.</ref><br /> through 1,475 killed and missing and 2,383 wounded<ref name="Piotr_p199">Piotrowski, p. 199.</ref><br /> to about 2,500 dead or missing<ref name="PWN_KW_old"/><br /> or 3,000 dead and under 10,000 wounded (Polish estimates).<ref name="Sanford"/> | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Soviet invasion of Poland}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Polish September Campaign}} | |||

| {{Polish-Russian Wars}} | |||

| The ], which vastly outnumbered the Polish defenders, achieved its targets, encountering only limited resistance. Some 320,000 Poles were made prisoners of war.<ref name="Wojsko92" /><ref name="PWN" /> The campaign of mass persecution in the newly acquired areas began immediately. In November 1939 the ] ]. Some 13.5 million Polish citizens who fell under the ] were made Soviet subjects following ]s conducted by the ] secret police in an atmosphere of terror,<ref name="Stosunki">{{cite web|url=http://old.bialorus.pl/index.php?secId=49&docId=57&&Rozdzial=historia |title=Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką |publisher=Bialorus.pl |work=Internet Archive |date=2010 |access-date=26 December 2014 |author=Contributing writers |trans-title=Polish-Byelorussian relations under the Soviet occupation |url-status=unfit |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100529211839/http://old.bialorus.pl/index.php?secId=49&docId=57&&Rozdzial=historia |archive-date=29 May 2010 }}</ref><ref name="Wierzbicki2000">{{cite book|author=Marek Wierzbicki|title=Polacy i białorusini w zaborze sowieckim: stosunki polsko-białoruskie na ziemach północno-wschodnich II Rzeczypospolitej pod okupacją sowiecką 1939–1941|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hMMqAAAAMAAJ|year=2000|publisher=Volumen|isbn=978-83-7233-161-8}}</ref><ref name="Wegner-74">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aESBIpIm6UcC&pg=PA74 |title=From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939–1941 |publisher=Berghahn Books |year=1997 |access-date=26 December 2014 |author=Bernd Wegner |author-link = Bernd Wegner |page=74 |isbn=1-57181-882-0}}</ref> the results of which were used to legitimise the use of force. A ], targeting Polish figures of authority such as military officers, police, and priests, began with a wave of arrests and ]s.{{#tag:ref|{{cite book |quote=In September, even before the start of the Nazi atrocities that horrified the world, the Soviets began their own program of systematic individual and mass executions. On the outskirts of Lwów, several hundred policemen were executed at one time. Near Łuniniec, officers and noncommissioned officers of the Frontier Defence Cops together with some policemen, were ordered into barns, taken out and shot ... after December 1939, 300 Polish priests were killed. And there were many other such incidents. |url=https://archive.org/details/polandsholocaust00piot |url-access=registration |title=Poland's Holocaust |author=Tadeusz Piotrowski |publisher=McFarland |year=1998 |page= |isbn=0-7864-0371-3}}|group="Note"}}<ref name="Rummel 130" /><ref name="Rieber 30" /> The Soviet NKVD sent hundreds of thousands of people from eastern Poland to ] and other remote parts of the Soviet Union in four major waves of deportation between 1939 and 1941.{{#tag:ref|The exact number of people deported between 1939 and 1941 remains unknown. Estimates vary between 350,000 and more than 1.5 million; Rummel estimates the number at 1.2 million, and Kushner and Knox 1.5 million.<ref name="Rummel 132" /><ref name="Kushner 219" />|group="Note"}} | |||

| The '''1939 Soviet invasion of Poland''' was a military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939, during the early stages of ], sixteen days after the beginning of the ] ]. It ended in a decisive victory for the ]'s ]. | |||

| Soviet forces occupied eastern Poland until the summer of 1941 when Germany terminated its earlier ] with the Soviet Union and invaded the Soviet Union under the code name ]. The area was under German occupation until the Red Army reconquered it in the summer of 1944. An agreement at the ] permitted the Soviet Union to annex territories close to the ] (which almost coincided with all of their Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact portion of the ]), compensating the ] with the greater southern part of ] and territories east of the ].<ref name="Wettig 47" /> The Soviet Union appended the annexed territories to the ], ] and ]s.<ref name="Wettig 47" /> | |||

| After the ], the Soviet Union signed the ] with the new, internationally recognized Polish ] on 16 August 1945. This agreement recognized the status quo as the new official border between the two countries, with the exception of the region around ] and a minor part of ] east of the ] around ], which were later returned to Poland.<ref name="Fertacz">{{cite web|url= http://www.alfa.com.pl/slask/200506/s19.html |title= Bolesna granica, 1945: KROJENIE MAPY POLSKI |date=18 December 2007 |publisher= Archive |author=SYLWESTER FERTACZ |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20090425133017/http://www.alfa.com.pl/slask/200506/s19.html |access-date =19 September 2020|archive-date= 25 April 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| Since 1935 Stalin wanted a nonaggression pact with Nazi Germany rather than an alliance with Britain and France. In early 1939, the Soviet Union allegedly tried to form an alliance against Nazi Germany with the ], ], ], and ]; but several difficulties arose, including the Soviet demand that Poland and Romania allow Soviet troops transit rights through their territories as part of ].<ref name="Cienciala">] (2004). (lecture notes, ]). Retrieved 15 March 2006.</ref> With the failure of the negotiations, the Soviets on 23 August 1939 signed the ] with Nazi Germany. As a result, on 1 September, the Germans invaded Poland from the west; and on 17 September, the Red Army invaded Poland from the east.<ref>German diplomats had urged the Soviet Union to intervene against Poland from the east since the beginning of the war. Roberts, Geoffrey (1992). . '']'' 44 (1), 57–78; @ ] and some following documents. The Soviet Union was reluctant to intervene as ] hadn't yet fallen. The Soviet decision to invade the eastern portions of Poland earlier agreed as the Soviet zone of influence was communicated to the German ambassador ] on 9 September, but the actual invasion was delayed for more than a week. Roberts, Geoffrey (1992). . '']'' 44 (1), 57–78; @ ]. Polish intelligence became aware of the Soviet plans around 12 September.</ref> The Soviet government pretended that it was acting to protect the ] and ] who lived in the ], because the Polish state had collapsed in the face of the German attack and could no longer guarantee the security of its own citizens.<ref name="SCHULENBURG">Telegrams sent by ], German ambassador to the Soviet Union, from Moscow to the German Foreign Office: of 10 September 1939, of 16 September 1939, of 17 September 1939. The ], ]. Retrieved 14 November 2006.</ref><ref name = "note">{{pl icon}} (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939, refused by Polish ambassador ]). Retrieved 15 November 2006; Degras, pp. 37–45. </ref> | |||

| ==Prelude== | |||

| The Red Army quickly achieved its targets, vastly outnumbering Polish resistance.<ref name="Wojsko">{{pl icon}} ''''. 1/2005. Dom wydawniczy Wojska Polskiego. (Humanist Education in the Army.) 1/2005. Publishing House of the Polish Army). Retrieved 28 November 2006.</ref> About 230,000 Polish soldiers or more (452,500<ref>M.I.Mel'tyuhov. Stalin's lost chance. The Soviet Union and the struggle for Europe 1939–1941, p.132. Мельтюхов М.И. Упущенный шанс Сталина. Советский Союз и борьба за Европу: 1939–1941 (Документы, факты, суждения). — М.: Вече, 2000.</ref>) were taken ].<ref name="PWN">{{pl icon}} (Prison camps for Polish soldiers). ]. Retrieved 28 November 2006.</ref> The Soviet government ] and in November declared that the 13.5 million Polish citizens who lived there were now Soviet citizens. The Soviets ] by ] and by arresting thousands.<ref>Rummel, p.130; Rieber, p. 30.</ref> According to data published by ] in 2009, they sent 320,000 to ] and other remote parts of the USSR in four major waves of ]s between 1939 and 1941.<ref name = "ipn2009" > </ref>. IPN estimates the number of Polish citizens who perished under the Soviet rule during World War II at 150,000.<ref name=ipn2009/>. Some earlier estimates cited much higher numbers of victims. {{Ref_label|b|b|1}} | |||

| In early 1939, several months before the invasion, the Soviet Union began strategic alliance negotiations with the ] and ] against the crash militarization of Nazi Germany under ]. | |||

| ] pursued the ] with Adolf Hitler, which was signed on 23 August 1939. This ] contained a secret protocol, that drew up the division of Northern and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence in the event of war.<ref name="Watson 695-722" /> One week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, German forces invaded Poland from the west, north, and south on 1 September 1939. Polish forces gradually ] where they prepared for a long defense of the ] and awaited the French and British support and relief that they were expecting, but neither the French nor the British came to their rescue. On 17 September 1939 the Soviet ] invaded the ] regions in accordance with the secret protocol.<ref name="Kitchen 74" />{{#tag:ref|The Soviet Union was reluctant to intervene until the fall of ] to the Germans.<ref name="Davies96 1001" /> The actual attack was delayed for more than a week after the decision to invade Poland was already communicated to the German ambassador ] on 9 September. The Soviet zone of influence according to the pact was carved out through tactical operations.<ref name="Roberts 74" />|group="Note"}} | |||

| The Soviet ], which the ] called "the liberation campaign", led to the incorporation of millions of Poles, western Ukrainians, and western Belarusians into the Soviet ] and ] ].<ref>Rieber, p 29.</ref> During the existence of the ], the invasion was a ] subject in Poland, almost omitted from the official history in order to preserve the illusion of "eternal friendship" between members of the ].<ref name="Ferro"/> | |||

| At the opening of hostilities several Polish cities including Dubno, Łuck and Włodzimierz Wołyński let the Red Army in peacefully, convinced that it was marching on in order to fight the Germans. General ] of the Polish Army issued an unauthorised order to treat them like an ally before it was too late.<ref name="Wywiał-IPN">{{cite book |url=http://ipn.gov.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/70275/1-34074.pdf |title=Działania militarne w Wojnie Obronnej po 17 września |trans-title=Military operations after 17 September |publisher=] |work=Komentarze historyczne, Nr 8–9 (129–130) |date=August 2011 |access-date=22 December 2014 |author=Przemysław Wywiał |pages=70–78 |archive-date=17 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160317033211/http://ipn.gov.pl/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/70275/1-34074.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> The Soviet government announced it was acting to protect the ] and ] who lived in the eastern part of Poland, because the Polish state had collapsed – according to ], which perfectly echoed Western sentiment that coined the term "Blitzkrieg" to describe Germany's "lightning war" crushing defeat of Poland after just weeks of battle<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/invasion-of-poland-fall-1939|title=The Invasion of Poland, Fall 1939 (last edited 25 August 2021)|last=The Holocaust Encyclopedia|access-date=14 January 2022}}</ref> – and could no longer guarantee the security of its citizens.<ref name="SCHULENBURG1" /><ref name="SCHULENBURG2" /><ref name="SCHULENBURG3" /><ref name="Degras 37-45" /> Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded that the defense of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all uniformed troops to then-neutral Romania.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> | |||

| ==Prelude== | |||

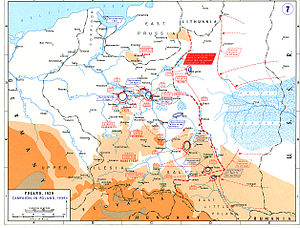

| ] 1939. Most Polish forces were concentrated on the German border; the Soviet border had been mostly stripped of units.]] | |||

| ==Poland between the two world wars== | |||

| In the late 1930s the Soviet Union tried to form an anti-German alliance with the ], ], and ].{{Ref_label|h|h|none}} The negotiations, however, proved difficult. The Soviets insisted on a sphere of influence stretching from Finland to Romania and asked for military support not only against anyone who attacked them directly but against anyone who attacked the countries in their proposed sphere of influence.<ref>Shaw, p 119; Neilson, p 298.</ref> From the beginning of the negotiations with France and Britain it was clear that Soviet Union demanded the right to occupy the ] (], ], and ]).<ref name="Grogin">"Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War 1917-1991" by Robert C. Grogin 2001 | |||

| The ] and the peace treaties of the 1919 ] did not, as it had been hoped, help to promote ideas of reconciliation along European ethnic lines. Epidemic nationalism, fierce political resentment in Central Europe (Germany, Austria, Hungary) where there was strong popular resentment to the War Guilt Clause, and post-colonial chauvinism (Italy) led to frenzied revanchism and territorial ambitions.<ref name="HobsbawmHobsbawm1992">{{cite book|author= Eric John Hobsbawm|title=Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality – pp. 130 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-MycJ9mCn14C|date=29 October 1992|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-43961-9}}</ref> ] sought to expand the Polish borders as far east as possible in an attempt to create a Polish-led federation, capable of countering future imperialist action on the part of Russia or Germany.<ref name="Roshwald 37" /> By 1920 the ] had emerged victorious from the ] and, de facto acquired exclusive control over the government and the regional administration. After all foreign interventions had been repelled, the Red Army, commanded by Trotsky and Stalin (among others) started to advance westward towards the disputed territories intending to encourage Communist movements in Western Europe.<ref name="Davies72 29" /> The Red Army eventually advanced deep into ] and ], and the embattled ] sought military help from Poland to repel the invasion. The joint Polish-Ukrainian armies initially successfully captured the Ukrainian capital, ], but eventually had to retreat following a massive counteroffensive by the Red Army, culminating in the ] of 1920.<ref name="Davies 22, 504" /> Following the Polish victory upon the ], the Soviets ] and the war ended with an armistice in October 1920.<ref name="Kutrzeba 524, 528" /> The parties signed a formal peace treaty, the ], on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia.<ref name="Davies 376" /> In an action that largely determined the Soviet-Polish border during the ], the Soviets offered the Polish peace delegation territorial concessions in the contested borderland areas, that closely resembled the border between the ] and the ] before the first ] of 1772.<ref name="Davies 504" /> In the aftermath of the peace agreement, the Soviet leaders steadily abandoned the idea of international Communist revolution and did not return to the concept for approximately 20 years.<ref name="Davies72 xi" /> The ] and the international community (with the exception of Lithuania) recognized Poland's eastern frontiers in 1923.<ref name="Lukowski" /><ref name="Gross 3" /> | |||

| Lexington Books page 28</ref> ] was to be included in the Soviet sphere of influence as well<ref name="Scandinavia">"Scandinavia and the Great Powers 1890-1940"Patrick Salmon 2002 Cambridge University | |||

| Press</ref> and the Soviets finally also demanded the right to enter Poland, ], and the Baltic States whenever they felt their security was threatened. The governments of those countries rejected the proposal because, as ] ] pointed out, they feared that once the Red Army entered their territories it might never leave.<ref name="Cienciala"/> The Soviets did not trust the British and French to honour ], since they had failed to ] against the ] or ] from the Nazis. They also suspected that the ] would prefer the Soviet Union to fight Germany by itself, while they watched from the sidelines.<ref>Kenez, A history of the Soviet Union from the beginning to the end, pp. 129–31.</ref> In view of these concerns the Soviet Union abandoned the talks and turned instead to negotiations with Germany. | |||

| ===Treaty negotiations=== | |||

| On 23 August 1939 the Soviet Union signed the ] with Nazi Germany, taking the allies by surprise. The two governments announced the agreement merely as a ]. As a secret ] reveals, however, they had actually agreed to partition Poland between themselves and divide ] into Soviet and German ].{{Ref_label|d|d|none}} The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which has been described as a license for war, was a key factor in Hitler’s decision to ].<ref name="Cienciala"/><ref>Davies, ''Europe: A History'', p. 997.</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact|German–Soviet Commercial Agreement (1939)|Polish–British Common Defence Pact}} | |||

| ] | |||

| German troops ] on 15 March 1939. In mid-April, the Soviet Union, Britain and France began trading diplomatic suggestions regarding a political and military agreement to counter potential further German aggression.<ref name="Watson 698" /><ref name="Gronowicz 51" /> Poland did not participate in these talks.<ref name="Neilson 275" /> The tripartite discussions focused on possible guarantees to participating countries should German expansionism continue.<ref name="Carley 303-341" /> The Soviets did not trust the British or the French to honour a collective security agreement, because they had refused to react against the ] during the ] and let the occupation of Czechoslovakia happen without effective opposition. The Soviet Union also suspected that Britain and France would seek to remain on the sidelines during any potential Nazi-Soviet conflict.<ref name="Kenéz 129-131" /> Robert C. Grogin (author of ''Natural Enemies'') contends that Stalin, had been "putting out feelers to the Nazis" through his personal emissaries as early as 1936 and desired a mutual understanding with Hitler as a diplomatic solution.<ref name="Grogin28">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qBBcqDludakC&q=1936%2BRibbentrop |title=Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, 1917–1991 |author=Robert C. Grogin |publisher=Lexington Books |year=2001 |isbn=0-7391-0160-9 |page=28}}</ref> The Soviet leader sought nothing short of an ironclad guarantee against losing his ],<ref name="Watson 695" /> and aspired to create a north–south buffer zone from Finland to Romania, conveniently established in the event of an attack.<ref name="Shaw 119" /><ref name="Neilson 298" /> The Soviets demanded the right to enter these countries in case of a security threat.<ref name="Watson 708" /> Talks on military matters, that had begun in mid-August, quickly stalled over the topic of Soviet troop passage through Poland in the event of a German attack. British and French officials pressured the Polish government to agree to the Soviet terms.<ref name="Watson 713" /><ref name="Shirer 536" /> However, Polish officials bluntly refused to allow Soviet troops to enter Polish territory upon expressing grave concerns that once Red Army troops had set foot on Polish soil, they might decline demands to leave.<ref name="Shirer 537" /> Thereupon Soviet officials suggested that Poland's objections be ignored and that the tripartite agreements be concluded.<ref name="Neilson 315" /> The British refused the proposal, fearing that such a move would encourage Poland to establish stronger bilateral relations with Germany.<ref name="Neilson 311" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| German officials had secretly been forwarding hints towards Soviet channels for months already, alluding that more favourable terms in a political agreement would be offered than Britain and France.<ref name="Roberts 66-73" /> The Soviet Union had meanwhile started discussions with Nazi Germany regarding the establishment of an economic agreement while concurrently negotiating with those of the tripartite group.<ref name="Roberts 66-73" /> By late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German diplomats had reached a near-complete consensus on the details for a planned economic agreement and addressed the potential for a desirable political accord.<ref name="Shirer 503" /> On 19 August 1939, German and Soviet officials concluded the ], a mutually beneficial economic treaty that envisaged the trade and exchange of Soviet raw materials for German weapons, military technology and civilian machinery. Two days later, the Soviet Union suspended the ].<ref name="Roberts 66-73" /><ref name="Shirer 525" /> On 24 August, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the political and military arrangements following the trade agreement, in the ]. This pact included terms of mutual non-aggression and contained secret protocols, that regulated detailed plans for the division of the states of ] and eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence. The Soviet sphere initially included ], ] and ].{{#tag:ref|On 28 September, the borders were redefined by adding the area between the Vistula and Bug rivers to the German sphere and moving Lithuania into the Soviet sphere.<ref name="Sanford 21" /><ref name="Weinberg 963" />|group="Note"}} Germany and the Soviet Union would partition Poland. The territories east of the ], ], ], and ] rivers would fall to the Soviet Union. The pact also provided designs for the Soviet participation in the invasion,<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|last=Davies|first=Norman|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1000049817|title=Europe : a history|date=2014|isbn=978-1-4070-9179-2|location=London|pages=2568|oclc=1000049817}}</ref> that included the opportunity to regain territories ceded to Poland in the ] of 1921.<ref name=":2" /> The Soviet planners would enlarge the Ukrainian and Belarusian republics to subjugate the entire eastern half of Poland without the threat of disagreement with Adolf Hitler.<ref name="Dunnigan 132" /><ref name="Snyder 77" /> | |||

| The treaty provided the Soviets with extra defensive space in the west.<ref name="Dunnigan">], </ref> It also offered them a chance to regain territories ceded to Poland ] and to unite the eastern and western Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples under a Soviet government, for the first time in the same state.<ref>Sanford, pp. 20–25; ], </ref> Soviet leader ] saw advantages in a war in western Europe, which might weaken his ideological enemies and open up new regions to the advance of ].<ref name="Gelven">], </ref>{{Ref_label|f|f|none}} | |||

| One day after the German-Soviet pact had been signed, French and British military delegations urgently requested a meeting with Soviet military negotiator ].<ref name="Shirer 541" /> On 25 August Voroshilov acknowledged, that ''"in view of the changed political situation, no useful purpose can be served in continuing the conversation."''<ref name="Shirer 541" /> On the same day, however, Britain and Poland signed the ],<ref name="Osmańczyk-Mango 231">] p. 231</ref> which adjudicated, that Britain commit itself to defend and preserve Poland's sovereignty and independence.<ref name="Osmańczyk-Mango 231" /> | |||

| Soon after the Germans ] Poland on 1 September 1939, the Nazi leaders began urging the Soviets to play their agreed part and attack Poland from the east. The German ambassador to ], ], and the Soviet ], ], exchanged a series of diplomatic communiqués on the matter.<ref name="SCHULENBURG"/> | |||

| ==German invasion of Poland and Soviet preparations== | |||

| {{quote|''Then Molotov came to the political side of the matter and stated that the Soviet Government had intended to take the occasion of the further advance of German troops to declare that Poland was falling apart and that it was necessary for the Soviet Union, in consequence, to come to the aid of the Ukrainians and the White Russians "threatened" by Germany. This argument was to make the intervention of the Soviet Union plausible to the masses and at the same time avoid giving the Soviet Union the appearance of an aggressor.''|Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg, German ambassador to Moscow in a ] to the German Foreign Office, Moscow, September 10 1939<ref></ref>}} | |||

| ] watching German soldiers marching into Poland in September 1939]] | |||

| Hitler tried to dissuade Britain and France from interfering in the forthcoming conflict and on 26 August 1939 proposed to make '']'' forces available to Britain in the future.<ref name="pledge" /> At midnight of 29 August, German Foreign Minister ] handed British Ambassador ] a list of terms that would allegedly ensure peace with regard to Poland.<ref name="Davies 371-373" /> Under the terms, Poland was to hand over Danzig (]) to Germany and within a year there was a plebiscite (]) to be held in the ], based on residency and demography of the year 1919.<ref name="Davies 371-373" /> When the Polish Ambassador ], who met Ribbentrop on 30 August, declared that he did not have the authority to approve of these demands on his own, Ribbentrop dismissed him<ref name="Mowat 648" /> and his foreign office announced that Poland had rejected the German offer and further negotiations with Poland were abandoned.<ref name="Henderson 16-18" /> On 31 August, in a ] operation German units, posing as regular Polish troops, staged the ] near the border town of ] in Silesia.<ref name="Whitehead2019">{{cite book|author=Dennis Whitehead|title=The Day Before the War: The Events of August 31, 1939 that Ignited World War II in Europe|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=htqsDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA62|date=26 August 2019|publisher=MMImedia LLC|isbn=978-88-341-7637-5|page=62}}</ref><ref name="Manvell-Fraenkel 76" /> On the following day (1 September) Hitler announced, that official military actions against Poland had commenced at 4:45 a.m.<ref name="Mowat 648" /> German air forces bombarded the cities ] and ].<ref name=strapol>{{cite web|url= http://www.hrono.ru/sobyt/1900war/1921zy.php |title= Борьба против польской оккупации на Западной Украине |publisher= Chrono Ru |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> Polish security service personnel carried out arrests among Ukrainian ] in Lwow and ].<ref name=strapol/> | |||

| There were several reasons why the Soviet invasion did not coordinate perfectly with the Nazi one. The Soviets were distracted by crucial events in their ]; they needed time to mobilize the Red Army.<ref name="Zaloga-blitz">], </ref><ref>Weinberg, p. 55.</ref> On 17 September 1939, Molotov declared on the radio that all treaties between the Soviet Union and Poland were now void,{{Ref_label|g|g|none}}. Moreover the Soviets might have taken into the consideration that ] and ] did promise Poland, in the case of war, to land ] forces within two weeks (via ]); the exact date of the Soviet invasion might have been simply a sum of the date that France and United Kingdom declared war on Germany plus 14 days, which equaled September 17, 1939. The failure of ] and the ] to help Poland either by sending expeditionary forces or by starting a full scale ground offensive against western Germany, or even by bombing the industrial areas of western Germany, might have prompted ] to invade.<ref>Degras, pp. 37–45. </ref> On the same day, the ] crossed the border into Poland.<ref name="Sanford"/><ref name="Zaloga-blitz">], p. 80.</ref> | |||

| On 1 September 1939 at 11:00 a.m. ], the counselor of the German embassy in Moscow, ] arrived at the ] and formally annunciated the beginning of the German–Polish War, the annexation of ] (]) as he conveyed a request of the ] that the radio station in ] provide signal support.<ref name=sov_pol39>{{cite web|url= http://hrono.ru/sobyt/1900war/1939pol.php |title= Советско-польская война |publisher= Chrono Ru |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> The Soviet side partially adhered to the request.<ref name=sov_pol39/> On the same day an extraordinary session of the ] confirmed the adoption of its ''"Universal Military Duty Act for males aged 17 years and 8 months old"'', by which the service draft act of 1937 was extended for another year.<ref name=sov_pol39/> Furthermore, the ] of the ] approved the proposal of the ], which envisaged that the ]'s existing 51 rifle divisions were to be supplemented to a total strength of 76 rifle divisions of 6,000 men, plus 13 mountain divisions and another 33 ordinary rifle divisions of 3,000 men.<ref name=sov_pol39/> | |||

| ==Military campaign== | |||

| {{seealso|German-Soviet military parade in Brest-Litovsk}} | |||

| ] 1939]] | |||

| On 2 September 1939 the German ] carried out a maneuver to envelop the forces of the Polish (]) that defended the "]",<ref name=sov_pol39/> with the result that the Polish commander General ] lost communication with his divisions.<ref name=sov_pol39/> The break-through of armored contingents of the German ] near the city of ] sought to defeat the Polish ] south of ] where the German 5th Armored Division had broken through towards ], that captured fuel depots and seized equipment warehouses.<ref name=sov_pol39/> To the east detachments of 18th corps of the German ] crossed the Polish–Slovak border near ].<ref name=sov_pol39/> The ] issued directive No. 1355-279сс that approved of the ''"Reorganization plan of the Red Army ground forces of 1939–1940"'',<ref name=sov_pol39/> which regulated detailed division transfers and updated territorial deployment plans for all the 173 future Red Army combat divisions.<ref name=sov_pol39/> In addition to the reorganized infantry, the number of corps artillery and the ] artillery was increased while the number of service units, rear units and institutions was to be reduced.<ref name=sov_pol39/> By the evening of 2 September enhanced defense and security measures were implemented at the Polish–Soviet border.<ref name=sov_pol39/> Per instruction No. 1720 of the border troop commander in the ], all detachments were set to permanent combat-ready status.<ref name=sov_pol39/> | |||

| The invasion was planned by Stalin, ], ], and ]. A few hours before it began, already on September 17, 1939, at 2 a.m., Stalin, with Molotov and Voroshilov, informed German ambassador in Moscow, ], that Soviet troops would soon cross the border. Stalin said: "At 6 a.m., four hours from now, the Red Army will cross into Poland".<ref name="Simon Sebag Montefiore page 312"></ref> | |||

| The governments of allied Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September, but neither undertook agreed-upon military action nor provided any substantial support for Poland.<ref name="Forczyk2019">{{cite book|author=Robert Forczyk|title=Case White: The Invasion of Poland 1939|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K3C1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA142|date=31 October 2019|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|isbn=978-1-4728-3493-5|page=229}}</ref><ref name="Mowat 648-650" /> Despite notable Polish success in local border battles, German technical, operational and numerical superiority eventually required the retreat of all Polish forces from the borders towards shorter lines of defense at Warsaw and ]. On the same day (3 September), the new Soviet Ambassador in ] ] handed his ] to ].<ref name=sov_pol39/> During the initiation ceremony Shkvartsev and Hitler reassured each other on their commitment to fulfill the terms of the non-aggression agreement.<ref name=sov_pol39/> ] ] commissioned the German Embassy in Moscow with the assessment of and the report on the likelihood of Soviet intentions for a Red Army invasion into Poland.<ref name=sov_pol39/> | |||

| The Red Army entered the ] with seven ] and between 450,000 and 1,000,000 troops.<ref name="Sanford"/> These were deployed on two ]: the ] under ], and the ] under ].<ref name="Sanford"/> By this time, the Poles had already failed to ], and in response to German incursions had launched a major counter-offensive in the ]. The Polish Army originally had a well-developed ], but was unprepared to face two invasions at once; nor did the Polish military strategists believe that it made any sense to offer more than a token resistance if attacked by both the Germans and the Soviets. However, in spite of that belief, the polish military had not developed an ] plan for this contingency, leading to the death and capture of many Polish soldiers who engaged in an uncoordinated and ineffective defense.<ref name="Wschód">Szubański, ''Plan operacyjny "Wschód"''.</ref> By the time the Soviets invaded, the Polish commanders had sent most of their troops west to face the Germans, leaving the east protected by only twenty under-strength battalions. These battalions consisted of about 20,000 troops of border defence corps, or '']'', under the command of general ].<ref name="Wojsko"/><ref name="Sanford">], </ref> | |||

| On 4 September 1939 all German navy units in the northern Atlantic Ocean received order "to follow to ], via the northernmost course".<ref name=sov_pol39/> On the same day, the ] and the ] approved of the People's Commissar of Defense ]'s orders to delay retirement and dismissal of Red Army personnel and young commanders for one month and to initiate full-scale training for all air defense detachments and staff in Leningrad, Moscow, Kharkov, in Belorussia and the Kiev Military District.<ref name=sov_pol39/> | |||

| ] | |||

| On 5 September 1939 the People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs ] received the German Ambassador ].<ref name=sov_pol39/> Upon the ambassador's inquiry with regards to a possible deployment of the Red Army into Poland, Molotov answered that the Soviet government ''"will definitely have to... start specific actions"'' at the right time. ''"But we believe that this moment has not yet come"'' and ''"any haste may ruin things and facilitate the rallying of opponents"''.<ref name=sov_pol39/> | |||

| At first, the Polish ], ] ], ordered the border forces to resist the Soviet invasion, but changed his orders after consulting with ] ], commanding them to fall back and engage the Soviets only in self-defense.<ref name="Wojsko"/><ref name="Gross">Gross, p. 17.</ref> | |||

| On 10 September, the Polish commander-in-chief, Marshal ], ordered a ] to the southeast towards the ].<ref name="Stanley 29" /> Soon after, Nazi German officials further urged their Soviet counterparts to uphold their agreed-upon part and attack Poland from the east. Molotov and ambassador von der Schulenburg discussed the matter repeatedly but the Soviet Union nevertheless delayed the invasion of eastern Poland, while being occupied with events unfolding in the ] in relation to the ongoing ] with Japan. The Soviet Union needed time to mobilize the Red Army and utilized the diplomatic advantage of waiting to attack after Poland had disintegrated.<ref name="Zaloga 80" /><ref name="Weinberg 55" /> | |||

| {{quote|''The Soviets have entered. I order a general retreat to Romania and Hungary by the shortest route. Do not fight the ]s unless they assault you or try to disarm your units. The tasks for Warsaw and cities which were to defend themselves from the Germans - without changes. Cities aproached by Bolsheviks should negotiate the issue of withdrawing the garrison to Hungary or Romania.''|Edward Rydz-Śmigły, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish armed forces, September 17 1939}}<ref>''Sowiety wkroczyły. Nakazuję ogólne wycofanie na Rumunię i Węgry najkrótszymi drogami. Z bolszewikami nie walczyć, chyba w razie natarcia z ich strony albo próby rozbrojenia oddziałów. Zadania Warszawy i miast które miały się bronić przed Niemcami - bez zmian. Miasta do których podejdą bolszewicy powinny z nimi pertraktować w sprawie wyjścia garnizonów do Węgier lub Rumunii.'' {{pl icon}}</ref> | |||

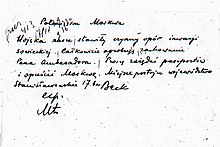

| On 14 September, with Poland's collapse at hand, the first statements on a conflict with Poland appeared in the Soviet press.<ref name="gunther1940">{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.149663/2015.149663.Inside-Europe#page/n15/mode/2up |title=Inside Europe |publisher=Harper & Brothers |author=Gunther, John |location=New York|author-link=John Gunther|year=1940 |page=xviii}}</ref> The undeclared war between the ] and the ] at the ] had ended with the ]–] agreement, signed on 15 September as a ceasefire took effect on 16 September.<ref>Goldman p. 163, 164</ref>{{r|gunther1940}} On 17 September, Molotov delivered a declaration of war to ], the Polish Ambassador in Moscow: | |||

| ] | |||

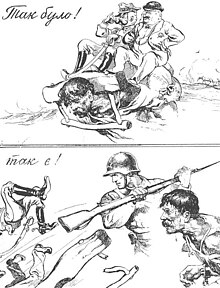

| The two conflicting sets of orders led to confusion,<ref name="Sanford"/> and when the Red Army advanced on Polish units, clashes and small battles inevitably broke out.<ref name="Wojsko"/> The response of non-ethnic Poles to the situation added a further complication. Many ],{{Ref_label|m|m|none}} ]<ref>Piotrowski, p 199.</ref> and ]s<ref>Gross, pp. 32–33.</ref> welcomed the invading troops as liberators. It was mentioned by ], who told Stalin that people of West Ukraine welcomed the Soviets "like true liberators".<ref name="Simon Sebag Montefiore page 312"/> The ] rebelled against the Poles, and communist partisans organized local uprisings, such as that in ].<ref name="Sanford"/>{{Ref_label|j|j|none}} | |||

| {{blockquote|Warsaw, as the capital of Poland, no longer exists. The Polish Government has disintegrated, and no longer shows any sign of operation. This means that the Polish State and its Government have, de facto, ceased to exist. Accordingly, the agreements concluded between the USSR and Poland have thus lost their validity. Left to her own devices and bereft of leadership, Poland has become a suitable field for all kinds of hazards and surprises, which may constitute a threat to the USSR. For these reasons the Soviet Government, who has hitherto been neutral, can no longer preserve a neutral attitude and ignore these facts. ... Under these circumstances, the Soviet Government has directed the High Command of the Red Army to order troops to cross the frontier and to take under their protection the life and property of the population of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus. <small>— People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the U.S.S.R. V. Molotov, 17 September 1939 </small><ref name="EM-WW2">Electronic Museum, 17 September 1939, by Vyacheslav M. Molotov; also ] {{in lang|ru}}, ] {{in lang|pl}}</ref>}} | |||

| The Polish military's original fall-back plan was to retreat and regroup along the ], an area in south-east Poland near the border with Romania. The idea was to adopt defensive positions there and wait for the much-expected French and British attack in the west. This plan assumed that Germany would have to reduce its operations in Poland in order to fight on a second front in Western Europe.<ref name="Sanford"/> The allies had expected Polish forces to hold out for up to several months, which whether or not it was ever realistic was quickly made impossible under the weight of a second front in the east. | |||

| Molotov declared via public radio broadcast that all treaties between the Soviet Union and Poland had become void, that the Polish government had abandoned its people as the Polish state had effectively ceased to exist.<ref name="Degras 37-45" /><ref name="Piotrowski 295" /> On the same day, the Red Army crossed the border into Poland.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Zaloga 80" /> | |||

| ] (center) and ] (right) at the ] in ].]] | |||

| ==Soviet invasion of Poland== | |||

| The Polish political and military leaders knew that they were losing the war against Germany even before the Soviet invasion settled the issue.<ref name="Sanford"/> Nevertheless, they refused to surrender or negotiate a peace with Germany, deciding to abandon the remaining areas of Poland under their control as indefensible and place their hopes in the Allies to retake Poland. In keeping with this new strategy, the Polish government ordered all military units to evacuate Poland and reassemble in ].<ref name="Sanford"/> The government itself crossed into ] at around midnight on 17 September 1939 through the border-crossing in ]. Polish units proceeded to manoeuvre towards the Romanian bridgehead area, sustaining German attacks on one flank and occasionally clashing with Soviet troops on the other. In the days following the evacuation order, the Germans defeated and disintegrated the Polish ] and ] at the ], which lasted from 17 September to 20 September.<ref>Taylor, p. 38.</ref> | |||

| ===Before invasion=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Soviet units often met their German counterparts advancing from the opposite direction. Several notable examples of co-operation occurred between the two armies in the field. The ] passed the ], which had been seized after the ], to the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade on 17 September.<ref name="Fischer">], "", ''Studies in Intelligence'', Winter 1999–2000. Retrieved 16 July 2007.</ref> The town was handed over by German army to the Soviets, with German withdrawal ceremony included<ref>Krivoshein S.M. Mezhduburie. Voronezh, 1964</ref> ].<ref name="Fischer"/> ] (Lviv) ] on 22 September, days after the Germans handed the siege operations over to the Soviets.<ref name="Leinwald">{{pl icon}} {{cite web | author=Artur Leinwand | title=Obrona Lwowa we wrześniu 1939 roku | publisher=Instytut Lwowski | year=1991 | work= | url=http://www.lwow.com.pl/rocznik/obrona39.html | accessdate= }} Retrieved 16 July 2007.</ref><ref name="Ryzinski"></ref> Soviet forces had taken ] on 19 September after ], and they took ] on 24 September after ]. By 28 September, the Red Army had reached the line formed by the Narew, Western Bug, Vistula and San rivers—the border agreed in advance with the Germans. | |||

| ], Polish minister of foreign affairs for ], Polish ambassador to the Soviet Union concerning the Soviet invasion of Poland, 17.09.1939]] | |||

| On the morning of 17 September 1939, the Polish administration was still fully operational throughout the entirety of the six easternmost ]s, and functioned partly within an additional five voivodeships in eastern Poland as schools remained open in mid-September 1939.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.rp.pl/artykul/355422-Zachod-okazal-sie-parszywienki.html?template=restricted |title= Zachód okazał się parszywieńki |date=28 August 2009 |publisher= Plus Minus |author= Piotr Zychowicz |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> Polish Army units concentrated their activities on two areas – on southern (], ], ]) and central (], ], and the ] river). Due to determined Polish defense and a lack of fuel, the German advance had stalled and the situation stabilized in the areas east of the line ] – ] – ] – ] – ] – ] – Lwów – ] – ] – ].<ref name="Czesław Grzelak page 242">{{cite book|author1=Czesław Grzelak|author2=Henryk Stańczyk|title=Kampania polska 1939 roku: początek II wojny światowej|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wO1mAAAAMAAJ|year=2005|publisher=Oficyna Wydawnicza "Rytm"|isbn=978-83-7399-169-9}}</ref> Rail lines were operational in approximately one-third of the territory of the country as both cross-border passenger and cargo traffic was maintained with five neighboring countries (Lithuania, Latvia, Soviet Union, Romania, and Hungary). In ], assembly of the ] planes continued in a PZL factory that had been moved out of Warsaw.<ref name="Leszek Moczulski 1939, p. 879">{{cite book|author=Robert Forczyk|title=Case White: The Invasion of Poland 1939|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TPSGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT251|date=31 October 2019|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|isbn=978-1-4728-3494-2}}</ref><ref name="Beck2019">{{cite book|author=Jürgen Beck|title=Die sowjetische Invasion Polens|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v56tDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT55|year=2019|publisher=Jazzybee Verlag|isbn=978-3-8496-5434-4|page=55}}</ref> A ] ship carrying ] tanks for Poland approached the Romanian port of ].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.2wojna.pl/encyklopedia-fr-wb-001.html |title= Renault R-35, R-40 |publisher= Encyklopedia Broni |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> Another ship, with artillery equipment, had just left ]. Altogether, seventeen French cargo ships were sailing towards Romania, carrying fifty tanks, twenty airplanes, and large quantities of ammunition and explosives.<ref name="Czesław Grzelak page 242" /> Several major cities were still in Polish hands, such as Warsaw, Lwów, Wilno, Grodno, Łuck, Tarnopol and Lublin (captured by German troops on 18 September). According to historian and author ], approximately 750,000 soldiers remained active in the Polish Army, whereas Czesław Grzelak and Henryk Stańczyk arrived at an estimated strength of 650,000 troops.<ref name="Czesław Grzelak page 242" /> | |||

| On 17 September 1939 the Polish Army, although weakened by weeks of fighting, still was a coherent force. Moczulski asserted, that the Polish Army was still bigger than most European armies and strong enough to fight the Wehrmacht for a long time.<ref name="Leszek Moczulski 1939, p. 879"/> On the ] – ] – ] line, rail transport of troops from the northeastern corner of the country towards the ] resumed day and night (among these troops were the ] under Colonel Jarosław Szafran,<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.lwow.home.pl/rocznik/obrona39.html |title= OBRONA LWOWA WE WRZEŚNIU 1939 ROKU |publisher= Lwow Home |author= Artur Leinwand |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> the so-called "] Group" ("Grupa grodzieńska") of Colonel Bohdan Hulewicz) and the second largest battle of the September Campaign – the ], started on the day of the Soviet invasion. According to Leszek Moczulski, around 250,000 Polish soldiers were fighting in central Poland, 350,000 were getting ready to defend the Romanian Bridgehead, 35,000 were north of ], and 10,000 were fighting on the Baltic coast of Poland, in ] and in ]. Due to the ongoing battles in the area around Warsaw, ], the ], at ], Lwów and Tomaszów Lubelski, most German divisions had been ordered to fall back towards these locations. The area that remained under control of the Polish authorities encompassed around {{convert|140000|sqkm|sqmi| abbr=on}} – approximately {{convert|200|km|mi| abbr=on}} wide and {{convert|950|km|mi| abbr=on}} long – from the ] in the north to the Carpathian Mountains in the south.<ref name="Czesław Grzelak page 242" /> ] and ] ceased to broadcast on 16 September after having been bombed by German ] units, while ] and ] still aired as of 17 September.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.taniaksiazka.pl/1939-ostatni-rok-pokoju-pierwszy-rok-wojny-andrzej-sowa-p-198296.html |title= 1939. Ostatni rok pokoju, pierwszy rok wojny- p. 569|publisher= Taniaksiazka |author= Janusz Osica, Andrzej Sowa, Paweł Wieczorkiewicz |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> | |||

| Despite a tactical Polish victory on 28 September at the ], the outcome of the larger conflict was never in doubt.<ref name="Interia-Szack"/> Civilian volunteers, ]s, and reorganised retreating units ], ], until 28 September. The ], north of Warsaw, surrendered the next day after ]. On 1 October, Soviet troops drove Polish units into the forests at the ], one of the last direct confrontations of the campaign.<ref name="Gen">Orlik-Rückemann, p. 20.</ref> | |||

| ===Opposing forces=== | |||

| Some isolated Polish ]s managed to hold their positions long after being surrounded, such as those in the ]n ] which held out until September 25, but the last operational unit of the Polish Army to surrender was General ]'s ''] (Samodzielna Grupa Operacyjna "Polesie")''. Kleeberg surrendered on 6 October after the four-day ] (near ]), which ended the September Campaign. The Soviets were victorious. On 31 October, ] reported to the ]: "A short blow by the German army, and subsequently by the Red Army, was enough for nothing to be left of this ugly creature of the ]".<ref>Moynihan, p. 93; Tucker, p. 612.</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Polish army order of battle in 1939|Soviet order of battle for invasion of Poland in 1939|Opposing forces in the Polish September Campaign}} | |||

| A Red Army force of seven ] with a combined strength between around 450,000 and 1,000,000 troops entered eastern Poland on two fronts.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> Polish sources give a number of over 800,000.<ref name="PWN_KW_old"/> ] ] commanded the invasion on the ] and ] ] led the Red Army on the invasion on the Belarusian Front.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> | |||

| When drawing up the defensive ] of 1938, Poland's military strategists assumed the Soviet Union would remain neutral during a conflict with Germany.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.strategie.com.pl/dzial/akademia/artykul/288 |title= Plan "Zachód" |publisher= Strategy PL |author=Yankees |access-date =19 September 2020}}</ref> As a result, Polish commanders focused on massive troop deployment designs and elaborate operational exercises in the west in order to successfully counter all German invasion attempts. This concept, however, would only leave a ] of approximately 20 under-strength battalions with a maximum strength of 20,000 troops assigned to defend the entire eastern border.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Wojsko90" /> During the Red Army invasion on 17 September, most Polish units had engaged in a fighting retreat towards the Romanian Bridgehead, where, according to overall strategic plans all divisions were to regroup and await new orders in coordination with allied British and French forces.{{fact|date=July 2024}} | |||

| ==Allied reaction== | |||

| ]. ]'s cartoon, published in the '']'' on 20 September 1939, shows Hitler greeting Stalin, following their joint ], with the words, "The scum of the earth, I believe?". To which Stalin replies, "The bloody assassin of the workers, I presume?"]] | |||

| ===Military campaign=== | |||

| The reaction of France and Britain to the Soviet invasion and annexation of Eastern Poland was muted, since neither country wanted to start a confrontation with the Soviet Union at that time.<ref name="prazmowska"/> Under the terms of the ] of 25 August 1939, the British had promised Poland assistance if attacked by a European power;{{Ref_label|k|k|none}} but when Polish Ambassador ] reminded ] ] of the pact, he was bluntly told that it was Britain's decision whether to declare war on the Soviet Union.<ref name="prazmowska"/> ] ] considered making a public commitment to restore the Polish state in the entirety of its pre-war territory, but in the end issued only general statements of condemnation:<ref name="prazmowska">Prazmowska, pp. 44–45.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Commander-in-chief ] was initially inclined to order the eastern border forces to oppose the invasion, but was dissuaded by ] ] and ] ].<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Wojsko90" /> At 4:00 a.m. on 17 September, Rydz-Śmigły ordered the Polish troops to fall back, stipulating that they only engage Soviet troops in self-defense.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> However, the German invasion had severely damaged the Polish communication systems and caused ] problems for the Polish forces.<ref name="Gross 17" /> In the resulting confusion, clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred along the border.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Wojsko90" /> General ], who took command of the Border Protection Corps on 30 August, received no official directives after his appointment.<ref name="Gross 17-18" /> As a result, he and his subordinates continued to actively engage Soviet forces, eventually dissolving the unit on 1 October.<ref name="Gross 17-18" /> | |||

| {{quote|Communism is now the great danger, greater even than Nazi Germany. It is a plague that does not stop at national boundaries, and with the advance of the Soviet into Poland the states of Eastern Europe will find their powers of resistance to Communism very much weakened. It is thus vital that we should play our hand very carefully with Russia, and not destroy the possibility of uniting, if necessary, with a new German government against the common danger.|Neville Chamberlain, October 1939}} | |||

| The Polish government refused to surrender or negotiate peace and instead ordered all units to leave Poland and reorganize in France.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> The day after the Soviet invasion had started, the Polish government withdrew into Romania. Polish units proceeded to manoeuvre towards the Romanian bridgehead area, repulsing German attacks on one flank and clashing occasionally with Soviet troops on the other. In the days following the evacuation order, the Germans defeated the ] and the ] at the ].<ref name="Taylor 38" /> | |||

| ] on the other hand issued another statement: | |||

| ] | |||

| Soviet units would meet their German counterparts during the advancement from opposite directions. Notable occurrences of co-operation in the field among the two armies were reported, for example, as ''Wehrmacht'' troops passed the ], which had been seized after the ] to the Soviet 29th Tank Brigade on 17 September.<ref name="Fischer" /> German General ] and Soviet Brigadier ] on 22 September held a joint ] in the town.<ref name="Fischer" /> ] (now ]) surrendered on 22 September, several days after German troops had abandoned their siege operation and allowed Soviet forces to take over.<ref name="Leinwald" /> Soviet forces took ] (now Vilnius) on 19 September after ], and ] on 24 September after ]. By 28 September, the Red Army reached the Narew – Western Bug – Vistula – San rivers line – the border that had been agreed upon in advance with Germany. | |||

| {{quote|That the Russian armies should stand on this line | |||

| was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against | |||

| the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is | |||

| there, and an Eastern Front has been created which | |||

| Nazi Germany does not dare assail. Whaen Herr von Ribbentrop was summoned to Moscow last week, it was to learn the fact, and to accept the fact, that the Nazi designs upon the Baltic States and upon the Ukraine must come to a dead stop.| Winston Churchill, September 1939<ref>Winston S. Churchill. Blood, Sweat, and Tears, p.173</ref>}} | |||

| Despite a tactical Polish victory on 28 September at the ], the outcome of the larger conflict was never in doubt.<ref name="Interia-Szack" /> Civilian volunteers, ] contingents and regrouped army units held out against German forces ], ], until the end of September, as the ], north of Warsaw, surrendered after ]. On 1 October, Soviet troops pushed Polish units into the forests at the ], during one of the last direct confrontations of the campaign.<ref name="Orlik-Rückemann 20" /> Several isolated Polish garrisons managed to hold their positions long after being surrounded, such as those in the ]n ] which only surrendered on 25 September. The last operational unit of the Polish Army was General ]'s ]. Kleeberg surrendered on 6 October after the four-day ], effectively ending the September Campaign. On 31 October, ] reported to the ]: "A short blow by the German army, and subsequently (by) the Red Army, was enough for nothing to be left of this (lit.) bastard (state) ({{langx|ru|ублюдок}}), created at the ]".<ref name="Moynihan 93" /><ref name="Tucker 612" /> | |||

| The French had also made promises to Poland, including the provision of air support, but also opted not to attack the USSR. Once the Soviets moved into Poland, the French and the British decided there was nothing they could do for Poland in the short term and began planning for a long-term victory instead. The French had advanced tentatively into the ] in early September, but after the Polish defeat, they retreated behind the ] on 4 October.<ref>Jackson, p. 75.</ref> Many Poles resented this lack of support from their western allies, which aroused a lasting sense of ]. | |||

| ===Domestic reaction=== | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Further|], ]}} | |||

| ].]]] | |||

| ]) captured by the Red Army after the Soviet invasion of Poland ]]] accepted by members of ] of ] - Document of decision of mass executions of Polish officers - POW - dated 5 March 1940. This image shows only the 1st page of the document, which tells about the alleged resistance movement among captured Polish officers. The 2nd page instructs the ] to apply ''"the supreme penalty: shooting"'' to 25,700 Polish prisoners.]] | |||

| The response of non-ethnic Poles to the situation caused considerable complications. Many ], ]ians and ]s welcomed the invading troops.<ref name="Gross 32-33" /> Local Communists gathered people to welcome the ] troops in the traditional Slavic way by presenting bread and salt in the eastern suburb of ]. A sort of ] on two poles, decked with spruce branches and flowers was fashioned for this occasion. A slogan in Russian on a long red banner, glorifying the ] and welcoming the Red Army, crowned the arch.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.vb.by/article.php?topic=36&article=14200 |script-title=ru:Радость была всеобщая и триумфальная |author=Юрий Рубашевский. |work=] |date=16 September 2011 |language=ru |access-date=15 December 2011 |archive-date=31 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131231001210/http://www.vb.by/article.php?topic=36&article=14200 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The event was recorded by ], who reported to Stalin that the people of the West Ukraine welcomed the Soviet troops "like true liberators".<ref name="Montefiore 312" /> The ] rebelled against Polish rule and Communist partisans stirred up local revolts, such as in ].<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ===International reaction=== | |||

| In October 1939, Molotov reported to the Supreme Soviet that the Soviets had suffered 737 deaths and 1,862 casualties during the campaign, though Polish specialists claim up to 3,000 deaths and 8,000 to 10,000 wounded.{{Ref_label|e|e|none}} On the Polish side, between 6,000 and 7,000 soldiers died fighting the Red Army, with 230,000 to 450,000 taken prisoner.<ref name="Wojsko"/><ref name="Отчёт">{{ru icon}} Отчёт Украинского и Белорусского фронтов Красной Армии Мельтюхов, с. 367. . Retrieved 17 July 2007.</ref> The Soviets often failed to honour terms of surrender. In some cases, they promised Polish soldiers freedom and then arrested them when they laid down their arms.<ref name="Sanford"/> | |||

| {{See also|Western betrayal}} | |||

| France and Britain refrained from a critical reaction to the Soviet invasion and annexation of Eastern Poland since neither country expected or wanted a confrontation with the Soviet Union at that time.<ref name="Prazmowska 44-45" /><ref name="Hiden-Lane 148" /> Under the terms of the ] of 25 August 1939, Britain had promised assistance if a European power attacked Poland.{{#tag:ref|The "Agreement of Mutual Assistance between the United Kingdom and Poland" (London, 25 August 1939) states in Article 1: "Should one of the Contracting Parties become engaged in hostilities with a European Power in consequence of aggression by the latter against that Contracting Party, the other Contracting Party will at once give the Contracting Party engaged in hostilities all the support and assistance in its power."<ref name="Stachura 125" />|group="Note"}} A secret protocol of the pact, however, specified that the European power referred to Germany.<ref name="Hiden-Lane 143-144" /> When Polish Ambassador ] reminded ] ] of the pact, he was bluntly told that it was Britain's exclusive right to declare war on the Soviet Union or not.<ref name="Prazmowska 44-45" /> ] ] considered making a public commitment to restore the Polish state but eventually issued only general condemnations.<ref name="Prazmowska 44-45" /> This stance represented Britain's attempt at balance as its security interests included trade with the USSR that would support its war effort and might lead to a possible future Anglo-Soviet alliance against Germany (which indeed happened two years later).<ref name="Hiden-Lane 143-144" /> Public opinion in Britain was varied among expressions of outrage at the invasion on the one hand and a perception that Soviet claims in the region were reasonable on the other.<ref name="Hiden-Lane 143-144" /> | |||

| While France had made promises to Poland, including the provision of air support, these were not honoured. A ] was signed in 1921 and amended thereafter. The agreements were not strongly supported by the French military leadership and the relationship deteriorated during the 1920s and 1930s.<ref name="Hehn 69-70" /> The French correctly considered the German-Soviet alliance to be fragile and overt denunciation of, or action against the Soviet Union would serve neither France's nor Poland's best interests.<ref name ="Hiden-Lane 148" /> Once the Soviets had occupied Poland, the French and the British realized there was nothing they could do for Poland on short notice and plans for a long-term victory were devised instead. The French forces, that had ], retreated behind the ] upon the Polish defeat on 4 October.<ref name="Jackson 75" /> | |||

| The Soviet Union had ceased to recognise the Polish state at the start of the invasion.<ref name="SCHULENBURG"/><ref name = "note">{{pl icon}} (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939, refused by Polish ambassador ]). Retrieved 15 November 2006.</ref> As a result, the two governments never officially declared war on each other. The Soviets therefore did not classify Polish military prisoners as prisoners of war but as rebels against the new legal government of Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia.{{Ref_label|n|n|none}} The Soviets killed tens of thousands of ]. Some, like General ], who was captured, interrogated and shot on 22 September, were executed during the campaign itself.<ref>Sanford, p. 23; {{pl icon}} , ]. Retrieved 14 November 2006.</ref><ref name="JOWIPN">{{pl icon}} Polish ]. Internet Archive, 16.10.03. Retrieved 16 July 2007.</ref> On 24 September, the Soviets killed forty-two staff and patients of a Polish military hospital in the village of ], near ].<ref name="Grabowiec">{{pl icon}} (Executed Hospital). Tygodnik Zamojski, 15 September 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2006.</ref> The Soviets also executed all the Polish officers they captured after the ], on 28 September 1939.<ref name="Interia-Szack">{{pl icon}} . ]. Retrieved 28 November 2006.</ref> Over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the ].<ref name="Sanford"/><ref name="Fischer"/> About 300 Poles were executed after the Battle of Grodno . | |||

| On 1 October 1939, ] stated in public: {{blockquote|... That the Russian armies should stand on this line was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is there, and an Eastern Front has been created which Nazi Germany does not dare assail. When Herr von Ribbentrop was summoned to Moscow last week it was to learn the fact, and to accept the fact, that the Nazi designs upon the Baltic States and upon the Ukraine must come to a dead stop.<ref name="Churchill2013">{{cite book|author=Winston S. Churchill|title=Into Battle, 1941|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iVwqAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT96|date=1 April 2013|publisher=Rosetta Books|isbn=978-0-7953-2946-3|page=96}}</ref>}}Since the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was not an official alliance,<ref name="Moorhouse20142">{{cite book|author=Roger Moorhouse|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xv5sAwAAQBAJ|title=The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939–1941|date=21 August 2014|publisher=Random House|isbn=978-1-4481-0471-0|page=4|quote=It is worth clarifying that the Nazi-Soviet Pact was not an alliance as such, it was a treaty of non-aggression. Consequently, aside from the metaphorical tide used here - The Devils' Alliance - I generally refrain from referring to Hitler and Stalin as 'allies' or their collaboration as an 'alliance'. However, that clarification should not blind us to the fact that the Nazi-Soviet relationship between 1939 and 1941 was a profoundly important one, which consisted of four further agreements after the pact of August 1939 and was, therefore, close to an alliance in many respects. Certainly it was far more vital and far more crucial to both sides than, for instance, Hitler's alliance with Mussolini's Italy. Hitler and Stalin were allies in all but name.}}</ref> modern scholarship has described the German and Soviet cooperation in the invasion of Poland as ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Hager|first=Robert P.|date=2017-03-01|title="The laughing third man in a fight": Stalin's use of the wedge strategy|url=https://online.ucpress.edu/cpcs/article-abstract/50/1/15/607/The-laughing-third-man-in-a-fight-Stalin-s-use-of?redirectedFrom=fulltext|journal=Communist and Post-Communist Studies|volume=50|issue=1|pages=15–27|doi=10.1016/j.postcomstud.2016.11.002|issn=0967-067X|quote=The Soviet Union participated as a cobelligerent with Germany after 17 September 1939, when Soviet forces invaded eastern Poland}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Blobaum|first=Robert|date=1990|title=The Destruction of East-Central Europe, 1939–41|url=https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/probscmu39&id=686&div=&collection=|journal=Problems of Communism|volume=39|pages=106|quote=As a co-belligerent of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union secretly assisted the German invasion of central and western Poland before launching its own invasion of eastern Poland on 17 September}}</ref> | |||

| ] was used on a wide scale in various prisons, especially those in small towns. Prisoners were scalded with boiling water in ]; in ], people had their noses, ears, and fingers cut off and eyes put out; in ], female inmates had their breasts cut off; and in ], victims were bound together with barbed wire. Similar atrocities occurred in ], ], ], and ].<ref>Gross, p. 181</ref> Also, in ]n town of ], ] broke out in January 1940, brutally suppressed by the Soviets. According to historian ]: | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| {{Main|Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)}} | |||

| ''"We cannot escape the conclusion: Soviet state security organs tortured their prisoners not only to extract confessions but also to put them to death. Not that the ] had sadists in its ranks who had run amok; rather, this was a wide and systematic procedure." <ref>Gross, p. 182</ref>'' | |||

| {{further|History of Poland (1939–1945)|Polish prisoners of war in Soviet Union (after 1939)}} | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ] | |||

| In October 1939, Molotov reported to the Supreme Soviet that the Red Army had suffered 737 deaths and 1,862 wounded men during the campaign, a casualty rate that widely contradicted Polish specialist's claims of up to 3,000 deaths and 8,000 to 10,000 wounded.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> On the Polish side, 3,000 to 7,000 soldiers died fighting the Red Army as between 230,000 and 450,000 men were taken prisoners.<ref name="Wojsko92" /> The Soviet troops regularly failed to honour commonly accepted terms of surrender. In some cases, after Polish soldiers had been promised to retreat freely Soviet troops arrested them once they had laid down their arms.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> | |||

| The Poles and the Soviets re-established diplomatic relations in 1941, following the ]; but the Soviets broke them off again in 1943 after the Polish government demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyn burial pits.<ref>Soviet note unilaterally severing Soviet-Polish diplomatic relations, 25 April 1943. Retrieved 19 December 2005; Sanford, p. 129.</ref> The Soviets then lobbied the Western Allies to recognise the pro-Soviet ] of ] in Moscow.<ref>Sanford, p. 127; Martin Dean Retrieved 15 July 2007.</ref> | |||

| ] soldier guarding a Polish ] trainer aircraft shot down near the city of Równe (]) in the Soviet occupied part of Poland, 18 September 1939]] | |||

| The Soviet Union had ceased to recognise the Polish state upon the start of the invasion. Neither side issued a formal declaration of war. This decision had significant consequences and Rydz-Smigly would be later criticised for it.<ref name="Sanford 22-23, 39" /> The Soviets killed tens of thousands of ] during the campaign itself.<ref name="Sanford 23" /> On 24 September, the Soviet soldiers killed 42 staff and patients of a Polish military hospital in the village of ], near ].<ref name="Grabowiec" /> Soviet troops also executed all the Polish officers they captured at the ] on 28 September 1939.<ref name="Interia-Szack" /> The ] killed 22,000 Polish military personnel and civilians in the ] in 1940.<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /><ref name="Fischer" /> ] was widely used by the NKVD in various prisons, especially in small towns.<ref name="Gross 182" /> | |||

| ]|alt=The front page of the Soviet document of decision, with blue hand writing scrawled across the left-center of the page, authorizing the mass execution of all Polish officers who were prisoners of war in the Soviet Union]] | |||

| On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany had changed the secret terms of the ]. They moved ] into the Soviet ] and shifted the border in Poland to the east, giving Germany more territory.<ref name="PWN_KW_old"/> By this arrangement, often described as a fourth ],<ref name="Sanford"/> the Soviet Union secured almost all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew, Western Bug and San. This amounted to about 200,000 square kilometres of land, inhabited by 13.5 million Polish citizens.<ref name="Gross">Gross, p. 17.</ref> | |||

| The Red Army had originally sown confusion among the |

On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the ], readdressing the secret terms of the ]. ] was incorporated into the Soviet ] and the border within Poland was shifted to the east, increasing German territory.<ref name="PWN_KW_old" /> By this arrangement, often described as a fourth ],<ref name="Sanford 20-24" /> the Soviet Union secured almost all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew, Western Bug and San. This amounted to about {{convert|200000|sqkm|sqmi| abbr=on}} territory, inhabited by 13.5 million Polish citizens.<ref name="Gross 17" /> The border created in this agreement roughly corresponded to the ] drawn by the British in 1919, a point that would successfully be utilized by Stalin during negotiations with the ] at the ] and ]s.<ref name="Dallas 557" /> The Red Army had originally sown confusion among the population, claiming that they had come to save Poland from Nazi occupation.<ref name ="Davies96 1001-1003">] pp. 1001–1003</ref> Their advance surprised Polish communities and their leaders, who had not been advised on how to respond to a Soviet invasion. Polish and Jewish citizens might initially have preferred Soviet rule to Nazi German rule.<ref name="Gross 24, 32-33" /> However, the Soviet authorities quickly imposed Communist ideology and administration upon their new subjects and suppressed the traditional ways of life. For instance, the Soviet government confiscated, ] and redistributed all private Polish property.<ref name="Piotrowski 11" /> During the two years following the annexation, the Soviet police forces arrested approximately 100,000 Polish citizens.<ref name="Karta" /> | ||

| In 2009 the Polish ] lowered this estimate to 320,000 deported and 150,000 dead <ref name="ipn2009" />. | |||

| The Poles and the Soviets re-established diplomatic relations in 1941, following the ]. The Soviets broke off talks again in 1943 after the Polish government had demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyn burial pits (]).<ref name="Soviet note of 1943" /><ref name="Sanford 129" /> | |||

| ===Territories of Second Polish Republic annexed by Soviet Union=== | |||

| {{Further|]}} | |||