| Revision as of 07:52, 13 July 2009 view sourceAsarlaí (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers33,721 edits revert: incorrect← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:18, 13 January 2025 view source Vauxhall Bridgefoot (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,912 edits →Other activities: changed tense, FS is now deadTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App section source | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Paramilitary force active from 1969 to 2005}} | |||

| {{Infobox War Faction | |||

| {{Redirect|PIRA|the association of physics education professionals and enthusiasts|Physics Instructional Resource Association|other uses|Pira (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | name = Provisional Irish Republican Army <br />(''Óglaigh na hÉireann'') | |||

| {{Redirect|Provos|the Dutch counterculture|Provo (movement)|the Christian martyr|Saint Probus of Side}} | |||

| | war = ] | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| {{Use Hiberno-English|date=August 2022}} | |||

| | caption = Masked Provisional IRA volunteers at a rally in August 1979 | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} | |||

| | active = 1969–1997 (formal end to the armed campaign was declared in 2005) | |||

| {{Infobox militant organization | |||

| | leaders = ] | |||

| | name = Provisional Irish Republican Army | |||

| | clans = | |||

| | image = Provisional Irish Republican Army Badge.svg | |||

| | headquarters = | |||

| | caption = A Provisional IRA badge, with the ] symbolising the group's origins. | |||

| | area = | |||

| | active = 1969–2005<br />(on ceasefire from 1997)<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=12.}}</ref> | |||

| | strength = ~10,000 over 30 years, ~1,000 in 2002, of which ~300 in active service units<ref>{{cite book | last = Moloney | first = Ed | authorlink = Ed Moloney | title = A Secret History of the IRA | publisher = ] |year=2002 | pages = xiv | doi = | isbn = 0-141-01041-X | nopp = true}}</ref> | |||

| | leaders = ]<ref name="moloneygac">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=377–379.}}</ref> | |||

| | previous = ] | |||

| | active2 = | |||

| | next = | |||

| | allegiance = {{flag|Irish Republic}}{{refn|group=n|The Provisional IRA rejected the legitimacy of the ], instead claiming its Army Council to be the provisional government of the ].<ref name="allegiance">{{harvnb|English|2003|p=106.}}</ref>}}<ref name="allegiance"/> | |||

| | allies = | |||

| | area = ],<ref name="extradition">{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|pp=433–434.}}</ref> ],<ref name="bowyerbellengland">{{harvnb|Bowyer Bell|2000|p=202.}}</ref> ]<ref name="cooganeurope">{{harvnb|Coogan|2000|pp=588–589.}}</ref> | |||

| | opponents = ] | |||

| | ideology = {{plainlist| | |||

| | battles = | |||

| * ]<ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=21.}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref name="socialism">{{harvnb|English|2003|p=369.}}</ref>}} | |||

| | size = 10,000 {{estimation}} throughout the Troubles<ref name="moloneyxviii">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=xviii.}}</ref> | |||

| | predecessor = ] (IRA) | |||

| | next = | |||

| | allies = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] (Irish Americans) <ref name="cooganlinks">{{harvnb|Coogan|2000|p=436.}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of Libya (1977–2011).svg}} ]<ref>{{harvnb|Geraghty|1998|p=180.}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flagdeco|Palestine}} ]<ref name="connections">{{harvnb|White|2017|p=392.}}</ref> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of the Basque Country.svg}} ]<ref name="connections"/> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of the FARC-EP.svg}} ]<ref name="connections"/> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | opponents = {{flagdeco|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| {{IrishR}} | |||

| * {{Army|United Kingdom}}<ref>{{harvnb|Dillon|1996|p=125.}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Provisional Irish Republican Army''' ('''IRA''') is an ] ] organisation that considers itself a direct continuation of the ] (the army of the '']'' — 1919–1921) that fought in the ]. Like other organisations calling themselves the IRA (see ]), the Provisionals' constitution establishes them as '']'' ("The Irish Volunteers") in the ], which is also the official title of the ]. The Provisional Irish Republican Army is sometimes referred to as the '''PIRA''', the '''Provos''', or by some of its supporters as the '''Army''' or the ''''RA.'''<ref>{{cite web | title = Grieving sisters square up to IRA | author = Henry McDonald| url = http://observer.guardian.co.uk/focus/story/0,6903,1411801,00.html | publisher = ''The Observer'' | date = 13 February 2005 | accessdate = 2007-07-20}}</ref> | |||

| * {{Flagicon image|Flag of the Royal Ulster Constabulary.svg|size=23px}} ]<ref name="targets">{{harvnb|Tonge|Murray|2005|p=67.}}</ref> | |||

| ]<ref>{{harvnb|Bowyer Bell|2000|p=1.}}</ref> | |||

| The IRA's ] is to end "British rule in Ireland," and according to its constitution, it wants "to establish an Irish Socialist Republic, based on the Proclamation of 1916."<ref>''The Long War: The IRA & Sinn Féin from Armed Struggle to Peace Talks'', O'Brien PRESS Ltd (Dublin 1993), ISBN 0 86278 359 3, pp. 9, 13, 19.</ref> Until the 1998 ], it sought to end ]'s status within the ] and bring about a ] by force of arms and political persuasion.<ref>Moloney, p. 246.</ref> The organisation is classified as a proscribed ] group in the United Kingdom and as an illegal organisation in the Republic of Ireland.<ref name=uk_illegal> — ] website, retrieved 11 May 2007</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = McDowell insists IRA will remain illegal | author = | url = http://www.rte.ie/news/2005/0828/mcdowellm.html | publisher = ] | date = 28 August 2005 | accessdate = 2007-05-18}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | battles = ]<ref name="hayes">{{harvnb|Hayes|McAllister|2005|p=602.}}</ref> | |||

| | native_name = {{langx|ga|Óglaigh na hÉireann}}<ref name="constitution">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=602–608.}}</ref> | |||

| | native_name_lang = Irish language | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Provisional Irish Republican Army''' ('''Provisional IRA'''), officially known as the '''Irish Republican Army''' ('''IRA'''; {{Langx|ga|]}}) and informally known as the '''Provos''', was an ] ] force that sought to end British rule in ], facilitate ] and bring about an independent republic encompassing all of ]. It was the most active republican paramilitary group during ]. It argued that the all-island ] continued to exist, and it saw itself as that state's army, the sole legitimate successor to the ] from the ]. It was ] in the United Kingdom and an unlawful organisation in the ], both of whose authority it rejected. | |||

| On 28 July 2005, the ] announced an end to ], stating that it would work to achieve its aims using "purely political and democratic programmes through exclusively peaceful means" and that IRA "] must not engage in any other activities whatsoever."<ref name="guardian.co.uk">{{cite web | title = Full text: IRA statement | author = | url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/Northern_Ireland/Story/0,,1537996,00.html | publisher = ''The Guardian'' | date = 28 July 2005 | accessdate = 2007-03-17}}</ref> In September 2008, the nineteenth report of the ] stated that the IRA was "committed to the political path" and no longer represented "a threat to peace or to democratic politics", and that the IRA's Army Council was "no longer operational or functional".<ref></ref><ref>"". ], 3 September 2008. Retrieved 2 April, 2009</ref> | |||

| The Provisional IRA emerged in December 1969, due to a split within ] and the broader ]. It was initially the minority faction in the split compared to the ] but became the dominant faction by 1972. The Troubles ] shortly before when a largely Catholic, nonviolent ] was met with violence from both ] and the ] (RUC), culminating in the ] and ]. The IRA initially focused on defence of Catholic areas, but it began ] that was aided by external sources, including ] communities within the ], and the ] and Libyan leader ]. It used ] tactics against the ] and RUC in both rural and urban areas, and carried out a bombing campaign in Northern Ireland and England against military, political and economic targets, and British military targets in mainland Europe. They also targeted civilian contractors to the British security forces. The IRA's armed campaign, primarily in Northern Ireland but also in England and mainland Europe, killed over 1,700 people, including roughly 1,000 members of the British security forces and 500–644 civilians. | |||

| An internal British Army document released in 2007 stated that the British Army had failed to defeat the IRA by force of arms but also claims to have "shown the IRA that it could not achieve its ends through violence." The military assessment describes the IRA as "professional, dedicated, highly skilled and resilient."<ref></ref> | |||

| The Provisional IRA declared a final ceasefire in July 1997, after which its political wing ] was admitted into multi-party peace talks on the future of Northern Ireland. These resulted in the 1998 ], and in 2005 the IRA formally ended its armed campaign and ] under the supervision of the ]. Several ]s have been formed as a result of splits within the IRA, including the ], which is still active in the ], and the ]. | |||

| {{TOClimit|limit=2}} | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| {{See also|Provisional Irish Republican Army campaign|History of Northern Ireland}} | |||

| ===1969 split in the IRA=== | |||

| According to modern ] theory, the two Irish governmental entities which have existed in Ireland since 1922, Northern Ireland and the state variously known at different times as the ] and the Republic of Ireland, were ], as they had been imposed by the British at the time of the ], in defiance of the last all-Ireland election in 1918, when the majority had voted for full independence. The ''real'' Irish state was the ], ] in 1919 and which, according to republican theory, was still in existence. According to this theory, the modern day Provisional Irish Republican Army is merely the continuation of the original ] which served as the army of the Irish Republic during the ]. | |||

| === Origins === | |||

| While at the time of Treaty and the subsequent ] the majority of the "old" IRA held this position, by the 1930s most republicans had accepted the Free State and were willing to work within it—recognising the ] as the state's armed force. However, a minority of republicans argued that the army of the Republic was still the pre-1969 ], itself the lineal descendant of the defeated faction in the Irish Civil War of 1922–23. Moreover, the ] was the legitimate government of Ireland until the Irish Republic could be re-established. This IRA in theory wanted to overthrow both Irish states, but by the late 1940s, it issued orders that "no armed action was to be taken against ] forces under any circumstances whatsoever". From then on, they concentrated on the overthrow of Northern Ireland, which was still part of the United Kingdom, but which contained a substantial Catholic and nationalist population. In the 1950s, the IRA waged a largely ineffective guerilla campaign against Northern Ireland, known as the "]". This was called off in 1962. | |||

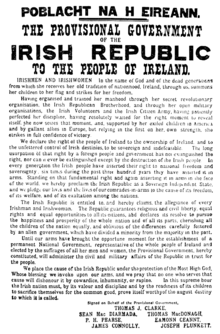

| ], issued during the 1916 ] against British rule in Ireland]] | |||

| The ] was formed in 1913 as the ], at a time when all of Ireland was part of the ].<ref name="taylororigins">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=8–10.}}</ref> The Volunteers took part in the ] against ] in 1916, and the ] that followed the ] by the revolutionary parliament ] in 1919, during which they came to be known as the IRA.<ref name="taylororigins"/> ] into ] and ] by the ], and following the implementation of the ] in 1922 Southern Ireland, renamed the ], became a self-governing ] while Northern Ireland chose to remain under ] as part of the United Kingdom.{{refn|group=n|The Irish Free State subsequently changed its name to Ireland and in 1949 became a ] fully independent of the United Kingdom.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=33.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=13–14.}}</ref> The Treaty caused a split in the IRA, the pro-Treaty IRA were absorbed into the ], which defeated the ] in the ].<ref name="white1921">{{harvnb|White|2017|p=21.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=18.}}</ref> Subsequently, while denying the legitimacy of the Free State, the surviving elements of the anti-Treaty IRA focused on overthrowing the Northern Ireland state and the achievement of a ], carrying out a ],<ref>{{harvnb|Oppenheimer|2008|pp=53–55.}}</ref> a ],<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|pp=67–70.}}</ref> and the ].<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=75.}}</ref> Following the failure of the Border campaign, internal debate took place regarding the future of the IRA.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=72.}}</ref> Chief-of-staff ] wanted the IRA to adopt a ] agenda and become involved in politics, while traditional republicans such as ] wanted to increase recruitment and rebuild the IRA.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=23.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=45.}}</ref> | |||

| Following partition, Northern Ireland became a ] governed by the ] in the ], in which Catholics were viewed as ]s.<ref>{{harvnb|Shanahan|2008|p=12.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Dillon|1990|p=xxxvi.}}</ref> ]s were given preference in jobs and housing, and ] were ] in places such as ].<ref name="tayloruvf">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=29–31.}}</ref> Policing was carried out by the armed ] (RUC) and the ], both of which were almost exclusively Protestant.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=19.}}</ref> In the mid-1960s tension between the Catholic and Protestant communities was increasing.<ref name="tayloruvf"/> In 1966 Ireland celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, prompting fears of a renewed IRA campaign.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=27.}}</ref> Feeling under threat, Protestants formed the ] (UVF), a ] group which killed three people in May 1966, two of them Catholic men.<ref name="tayloruvf"/> In January 1967 the ] (NICRA) was formed by a diverse group of people, including IRA members and liberal ].<ref name="whitecr">{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=47–48.}}</ref> Civil rights marches by NICRA and a similar organisation, ], protesting against discrimination were met by ]s and violent clashes with ], including the ], a paramilitary group led by ].<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=39–43.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=50.}}</ref> | |||

| The IRA split into two groups at its Special Army Convention in December 1969, over the issue of ] (whether to sit in or to "abstain" from the ] or parliament of the Republic of Ireland) and over the question of how to respond to the escalating violence in Northern Ireland (see ]). In 1969, serious rioting had broken out in ] following an ] march (]). Subsequently burning, damage or intimidation by ] forced 1,505 Catholics from their homes by in ] in the ], with over 200 Catholic homes being destroyed or requiring major repairs.<ref>''The Provisional IRA'' by Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie (ISBN 0-552-13337-X), p. 117.</ref> The IRA had been poorly armed and unable to adequately defend the Catholic community, as it had done since the 1920s.<ref>''The Provisional IRA'' by Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie (ISBN 0-552-13337-X), pp. 108–112.</ref> The two groups that emerged from the split became known as the ] (which espoused a ] analysis of ]) and the Provisional IRA. | |||

| Marches marking the Ulster Protestant celebration ] in July 1969 led to riots and violent clashes in ], Derry and elsewhere.<ref>{{harvnb|Munck|1992|p=224.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=47.}}</ref> The following month a three-day riot began in the Catholic ] area of Derry, following a march by the Protestant ].<ref name="taylorbogside">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=49–50.}}</ref> The ] caused Catholics in Belfast to riot in ] with the Bogsiders and to try to prevent RUC reinforcements being sent to Derry, sparking retaliation by Protestant mobs.<ref>{{harvnb|Shanahan|2008|p=13.}}</ref> The subsequent ]s, damage to property and intimidation forced 1,505 Catholic families and 315 Protestant families to leave their homes in Belfast in the ]<ref name="mb117">{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=117.}}</ref> The riots resulted in 275 buildings being destroyed or requiring major repairs, 83.5% of them occupied by Catholics.<ref name="mb117"/> A number of people were killed on both sides, some by the police, and the British Army were ].<ref name="taylor1969">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=49–54.}}</ref> The IRA had been poorly armed and failed to properly defend Catholic areas from Protestant attacks,<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|pp=108–112.}}</ref> which had been considered one of its roles since the 1920s.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=67.}}</ref> Veteran republicans were critical of Goulding and the IRA's Dublin leadership which, for political reasons, had refused to prepare for aggressive action in advance of the violence.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=60.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|pp=93–94.}}</ref> On 24 August a group including ], ], ], ], and ] came together in Belfast and decided to remove the pro-Goulding Belfast leadership of ] and ] and return to traditional militant republicanism.<ref name="mb125">{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=125.}}</ref> On 22 September Twomey, McKee, and Steele were among sixteen armed IRA men who confronted the Belfast leadership over the failure to adequately defend Catholic areas.<ref name="mb125"/> A compromise was agreed where McMillen stayed in command, but he was not to have any communication with the IRA's Dublin based leadership.<ref name="mb125"/> | |||

| The Official IRA did not want to get involved in what it considered to be divisive ] violence, nor did it want to launch an armed campaign against Northern Ireland, citing the failure of the IRA's ] in the 1950s. They favoured building up a political base among the ], both Catholic and Protestant, north and south, which would eventually undermine partition. This involved recognising and sitting in elected bodies north and south of the border. The Provisionals, by contrast, advocated a robust armed defence of Catholics in the north and an offensive campaign in Northern Ireland to end British rule there.<ref>''A Secret History of the IRA'' by Ed Moloney (ISBN 0-141-01-41-X), p. 85.</ref> They also denounced the "]" tendencies of the "Official" faction in favour of traditional Irish republicanism and non-] ], and they refused to recognise the legitimacy of either the northern or southern Irish states. | |||

| === |

=== 1969 split === | ||

| ] at the 1986 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis]] | |||

| ], who was twice ] of the ] during the ], was a member of the first ] of the Provisional IRA in 1969.<ref name="mallie137">{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=137.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=39–40.}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Provisional IRA had its origins in the "Provisional Army Council" formed in December 1969, when an ] voted to recognise the Parliaments of Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Opponents of this change in the IRA Constitution argued strongly against this, and when the vote took place, ], present as IRA Director of Intelligence, announced that he no longer considered that the IRA leadership represented Republican goals.<ref>Mallie, Bishop p. 136.</ref> However, there was not a walkout. Those opposed, who include Mac Stíofáin and Ruairi O Bradaigh, did refuse to go forward for election to the new IRA Executive.<ref>Robert White, Ruairi O Bradaigh, the Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary, 2006, Indiana University Press.</ref> | |||

| The IRA split into "Provisional" and ] factions in December 1969,<ref name="taylorsplit">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=66–67.}}</ref> after an IRA convention was held in ], Republic of Ireland.<ref name="white1969gac">{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=64–65.}}</ref><ref name="hanley145">{{harvnb|Hanley|Millar|2010|p=145.}}</ref> The two main issues at the convention were a ] to enter into a "National Liberation Front" with radical left-wing groups, and a resolution to end ], which would allow participation in the ], ], and Northern Ireland parliaments.<ref name="white1969gac"/> Traditional republicans refused to vote on the "National Liberation Front", and it was passed by twenty-nine votes to seven.<ref name="white1969gac"/><ref name="horgantaylor">{{harvnb|Horgan|Taylor|1997|p=152.}}</ref> The traditionalists argued strongly against the ending of abstentionism, and the ] report the resolution passed by twenty-seven votes to twelve.{{refn|group=n|The vote was a show of hands and the result is disputed.<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=136.}}</ref> It has been variously reported as twenty-eight votes to twelve,<ref name="white1969gac"/> or thirty-nine votes to twelve.<ref name="bowyerbell1969">{{harvnb|Bowyer Bell|1997|pp=366–367.}}</ref> The official minutes state out of the forty-six delegates scheduled to attend, thirty-nine were in attendance, and the result of the second vote was twenty-seven votes to twelve.<ref name="horgantaylor"/>}}<ref name="white1969gac"/><ref name="horgantaylor"/> | |||

| Following the convention the traditionalists canvassed support throughout Ireland, with IRA director of intelligence Mac Stíofáin meeting the disaffected members of the IRA in Belfast.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=65.}}</ref> Shortly after, the traditionalists held a convention which elected a ], composed of Mac Stíofáin, ], Paddy Mulcahy, Sean Tracey, ], Ó Conaill, and Cahill.<ref name="mallie137"/> The term provisional was chosen to mirror the 1916 ],<ref name="white1969gac"/> and also to designate it as temporary pending ] by a further IRA convention.{{refn|group=n|Following a convention in September 1970 the "Provisional" Army Council announced that the provisional period had finished, but the name stuck.<ref name="mallie137"/>}}<ref name="mallie137"/><ref>{{harvnb|White|1993|p=52.}}</ref> Nine out of thirteen IRA units in Belfast sided with the "Provisional" Army Council in December 1969, roughly 120 activists and 500 supporters.<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=141.}}</ref> The Provisional IRA issued their first public statement on 28 December 1969,<ref name=allegiance/> stating: | |||

| While others organised throughout Ireland, Mac Stiofain was a key person making a connection with the Belfast IRA, under ] and ], who had refused to take orders from the IRA's Dublin leadership since September 1969, in protest at their failure to defend Catholic areas in August 1969.<ref>''Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA'' by Richard English (ISBN 0-330-49388-4), p. 105.</ref> Nine out of thirteen IRA units in Belfast sided with the Provisionals in 1969, roughly 120 activists and 500 supporters.<ref>Mallie, Bishop p. 141.</ref> The new group elected a "Provisional Army Council" to head the new IRA. The first Provisional IRA Army Council was: Sean Mac Stiofain, C/S, Ruairi O Bradaigh, Paddy Mulcahy, Sean Tracey, Leo Martin, and Joe Cahill.<ref>Patrick Bishop and Eamonn Mallie, The Provisional IRA.</ref> A political wing, ], was founded on 11 January 1970, when a third of the delegates walked out of the Sinn Féin ] in protest at the party leadership's attempt to force through the ending of the abstentionist policy, despite its failure to achieve a two-thirds majority vote of delegates required to change the policy.<ref>{{cite book | last = Taylor | first = Peter | authorlink = Peter Taylor (Journalist) | title = Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin | publisher = ] |year=1997 | pages = 67 | doi = | isbn = 0-7475-3818-2 }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>We declare our allegiance to the 32 county Irish republic, proclaimed at Easter 1916, established by the first Dáil Éireann in 1919, overthrown by force of arms in 1922 and suppressed to this day by the existing British-imposed six-county and twenty-six-county partition states{{nbsp}}... We call on the Irish people at home and in exile for increased support towards defending our people in the North and the eventual achievement of the full political, social, economic and cultural freedom of Ireland.{{refn|group=n|The Provisional IRA issued all its public statements under the pseudonym "P. O'Neill" of the "Irish Republican Publicity Bureau, Dublin".<ref name=poneill>{{harvnb|BBC News Magazine 2005|ps=.}}</ref> ], the IRA's director of publicity, came up with the name.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2006|p=153.}}</ref> According to ], the pseudonym "S. O'Neill" was used during the 1940s.<ref name=poneill/>}}<ref name="bowyerbell1969"/></blockquote> | |||

| There are allegations that the early Provisional IRA got off the ground due to arms and funding from the ]-led ] in 1969. This was not found to be the case when investigated in the ]. However, roughly £100,000 was donated by the Irish government to "Defence Committees" in Catholic areas and according to historian ], "there is now no doubt that some money did go from the Dublin government to the proto-Provisionals".<ref>{{cite book | last = English | first = Richard | authorlink = | title = Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA | publisher = ] |year=2003 | pages = 119 | doi = | isbn = 0-330-49388-4 }}</ref> | |||

| The Irish republican political party ] split along the same lines on 11 January 1970 in Dublin, when a third of the delegates walked out of the party's highest deliberative body, the ], in protest at the party leadership's attempt to force through the ending of abstentionism, despite its failure to achieve a two-thirds majority vote of delegates required to change the policy.{{refn|group=n|When the resolution failed to achieve the necessary two-thirds majority to change Sinn Féin policy the leadership announced a resolution recognising the "Official" Army Council, which would only require a ] vote to pass.<ref name="taylorsplit"/> At this point ] led the walkout after declaring allegiance to the "Provisional" Army Council.<ref name="taylorsplit"/>}}<ref name="taylorsplit"/> The delegates that walked out reconvened at another venue where Mac Stíofáin, Ó Brádaigh and Mulcahy from the "Provisional" Army Council were elected to the Caretaker Executive of "Provisional" Sinn Féin.{{refn|group=n|The provisional period for "Provisional" Sinn Féin ended at an ard fheis in October 1970, when the Caretaker Executive was dissolved and an ] was elected, with ] becoming ].<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=78–79.}}</ref> ], president of the pre-split Sinn Féin since 1962,<ref>{{harvnb|Feeney|2002|p=219.}}</ref> continued as president of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Hanley|Millar|2010|p=482.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=67.}}</ref> Despite the declared support of that faction of Sinn Féin, the early Provisional IRA avoided political activity, instead relying on ].<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=104–105.}}</ref> £100,000 was donated by the ]-led ] in 1969 to the Central Citizens Defence Committee in Catholic areas, some of which ended up in the hands of the IRA.<ref name="armstrial"/><ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=265.}}</ref> This resulted in the 1970 ] where criminal charges were pursued against two former government ministers and others including ], an IRA ] from Belfast.<ref name="armstrial">{{harvnb|English|2003|p=119.}}</ref> The Provisional IRA maintained the principles of the pre-1969 IRA, considering both British rule in Northern Ireland and the government of the ] to be illegitimate, and the Army Council to be the ] of the all-island ].<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=66.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=107.}}</ref> This belief was based on a series of ] which constructed a legal continuity from the ] of 1921–1922.<ref name="obrien104">{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=104.}}</ref> The IRA recruited many young nationalists from Northern Ireland who had not been involved in the IRA before, but had been radicalised by the violence that broke out in 1969.<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|pp=151–152.}}</ref><ref name="moloney80">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=80.}}</ref> These people became known as "sixty niners", having joined after 1969.{{refn|group=n|The IRA also used "forties men" for volunteers such as ] who fought in the ],<ref>{{harvnb|Coogan|2000|p=366.}}</ref> and "fifties men" for volunteers who fought in the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Bowyer Bell|1990|p=16.}}</ref>}}<ref name="moloney80"/> The IRA adopted the ] as the symbol of the Irish republican rebirth in 1969, one of its slogans was "out of the ashes rose the Provisionals", representing the IRA's resurrection from the ashes of burnt-out Catholic areas of Belfast.<ref>{{harvnb|Shanahan|2008|p=14.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Nordstrom|Martin|1992|p=199.}}</ref> | |||

| The main figures in the early Provisional IRA were ] (who served as the organisation's first ]), ] (the first president of ]), ], and ]. All served on the first Provisional IRA Army Council.<ref>English, pp. 111–113.</ref> The Provisional appellation deliberately echoed the "Provisional Government" ] during the 1916 ].<ref>English, p. 106.</ref> | |||

| === Initial phase === | |||

| The Provisionals maintained a number of the principles of the pre-1969 IRA. It considered ] rule in Northern Ireland and the government of the Republic of Ireland to be illegitimate. Like the pre-1969 IRA, it believed that the IRA Army Council was the legitimate government of the all-island ]. This belief was based on a complicated series of perceived political inheritances which constructed a legal continuity from the ]. Most of these abstentionist principles were abandoned in 1986, although ] still refuses to take its seats in the ].<ref>Taylor, pp. 289–291.</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Northern Ireland: The SDLP and the House of Lords | author = Robin Sheeran | url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/politics_show/4628112.stm | publisher = ''BBC'' | date = 21 January 2006 | accessdate = 2007-03-27}}</ref> | |||

| ] was part of an IRA delegation which took part in peace talks with British politician ], the ], in July 1972.<ref name="taylor1972"/>]] | |||

| As the violence in Northern Ireland steadily increased, both the Official IRA and Provisional IRA espoused military means to pursue their goals. Unlike the Officials, however, who characterised their violence as purely "defensive," the Provisionals called for a more aggressive campaign against the Northern Ireland state. While the Officials were initially, for a short period, the larger organisation and enjoyed more support from the republican community, the Provisionals came to dominate, especially after the Official IRA declared an indefinite ceasefire in 1972. The Provisionals inherited most of the existing IRA organisation in the north by 1971 and the more militant IRA members in the rest of Ireland. In addition they recruited many young nationalists from the north, who had not been involved in the IRA before, but had been radicalised by the communal violence that broke out in 1969. These people were known in republican parlance as "sixty niners", having joined after 1969.<ref>Moloney, p. 80.</ref> | |||

| In January 1970, the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army.<ref name="english125">{{harvnb|English|2003|p=125.}}</ref> The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide.<ref>{{harvnb|Sanders|2012|p=62.}}</ref> The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the ] and to inflict such heavy casualties on the British Army that the British government would be forced by public opinion to withdraw from Ireland.<ref name="smith9799">{{harvnb|Smith|1995|pp=97–99.}}</ref> Mac Stíofáin decided they would "escalate, escalate and escalate", in what the British Army would later describe as a "classic ]".<ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=119.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Mulroe|2017|p=21.}}</ref> In October 1970 the IRA began a bombing campaign against economic targets; by the end of the year there had been 153 explosions.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=95.}}</ref> The following year it was responsible for the vast majority of the 1,000 explosions that occurred in Northern Ireland.<ref>{{harvnb|Ó Faoleán|2019|p=53.}}</ref> The strategic aim behind the bombings was to target businesses and commercial premises to deter investment and force the British government to pay compensation, increasing the financial cost of keeping Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.{{refn|group=n|In the early 1970s insurance companies cancelled ] for damage caused by bombs in Northern Ireland, so the British government paid compensation.<ref>{{harvnb|Quilligan|2013|p=326.}}</ref>}}<ref name="smith9799"/> The IRA also believed that the bombing campaign would tie down British soldiers in static positions guarding potential targets, preventing their deployment in ] operations.<ref name="smith9799"/> Loyalist paramilitaries, including the UVF, carried out campaigns aimed at thwarting the IRA's aspirations and maintaining the political union with Britain.<ref>{{harvnb|Dingley|2008|p=45.}}</ref> Loyalist paramilitaries tended to target Catholics with no connection to the republican movement, seeking to undermine support for the IRA.{{refn|group=n|This was due to the difficulty in identifying members of the IRA, ease of targeting, and many loyalists believing ordinary Catholics were in league with the IRA.<ref name="shanahanloyalists">{{harvnb|Shanahan|2008|pp=207–208.}}</ref>}}<ref name="shanahanloyalists"/><ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=118.}}</ref> | |||

| As a result of escalating violence, ] was introduced by the Northern Ireland government on 9 August 1971, with 342 suspects arrested in the first twenty-four hours.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=92.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=139.}}</ref> Despite loyalist violence also increasing, all of those arrested were republicans, including ]s not associated with the IRA and student civil rights leaders.<ref name="smith1971">{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=101.}}</ref><ref name="moloneyinternment">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=101–103.}}</ref> The one-sided nature of internment united all Catholics in opposition to the government, and riots broke out in protest across Northern Ireland.<ref name="smith1971"/><ref name="englishinternment">{{harvnb|English|2003|pp=140–141.}}</ref> Twenty-two people were killed in the next three days, including six civilians killed by the British Army as part of the ] on 9 August,<ref name="moloneyinternment"/><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=83.}}</ref> and in Belfast 7,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants were forced from their homes by the rioting.<ref name="moloneyinternment"/> The introduction of internment dramatically increased the level of violence. In the seven months prior to internment 34 people had been killed, 140 people were killed between the introduction of internment and the end of the year, including thirty soldiers and eleven RUC officers.<ref name="smith1971"/><ref name="moloneyinternment"/> Internment boosted IRA recruitment,<ref name="smith1971"/> and in Dublin the ], ], abandoned a planned idea to introduce internment in the Republic of Ireland.{{refn|group=n|Internment had been effective during the IRA's ] as it was used on both sides of the Irish border denying the IRA a safe operational base,<ref>{{harvnb|Geraghty|1998|p=43.}}</ref> but due to Lynch cancelling his plans IRA fugitives had a safe haven south of the border due to public sympathy for the IRA's cause.<ref name="moloneyinternment"/> The Republic of Ireland's Extradition Act 1965 contained a ] that prevented IRA members from being ] to Northern Ireland and numerous extradition requests were rejected before ] became the first republican paramilitary to be extradited in 1984.<ref name="extradition"/><ref>{{harvnb|Holland|McDonald|2010|pp=276–277.}}</ref>}}<ref name="moloneyinternment"/> IRA recruitment further increased after ] in Derry on 30 January 1972, when the British Army killed fourteen unarmed civilians during an anti-internment march.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=87–88.}}</ref> Due to the deteriorating security situation in Northern Ireland the British government suspended the Northern Ireland parliament and imposed ] in March 1972.<ref>{{harvnb|Mulroe|2017|pp=129–131.}}</ref> The suspension of the Northern Ireland parliament was a key objective of the IRA, in order to directly involve the British government in Northern Ireland, as the IRA wanted the conflict to be seen as one between Ireland and Britain.<ref name="smith9799"/><ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|pp=127–128.}}</ref> In May 1972 the Official IRA called a ceasefire, leaving the Provisional IRA as the sole active republican paramilitary organisation.{{refn|group=n|In 1974 ], an Official IRA member who led a faction opposed to its ceasefire, was expelled and formed the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|pp=279–280.}}</ref> This organisation remained active until 1994 when it began a "no-first-strike" policy, before declaring a ceasefire in 1998.<ref name="inla">{{harvnb|Holland|McDonald|2010|pp=464–467.}}</ref> Its armed campaign, which caused the deaths of 113 people, was formally ended in October 2009 and in February 2010 it ].<ref name="inla"/>}}<ref name="sanders">{{harvnb|Sanders|2012|p=53.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=93.}}</ref> New recruits saw the Official IRA as existing for the purpose of defence in contrast to the Provisional IRA as existing for the purpose of attack, increased recruitment and ]s from the Official IRA to the Provisional IRA led to the latter becoming the dominant organisation.{{refn|group=n|After the Official IRA's ceasefire, the Provisional IRA were typically referred to as simply the IRA.<ref>{{harvnb|O'Leary|2019a|p=61.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|Feeney|2002|p=270.}}</ref><ref name="sanders"/> | |||

| Although the Provisional IRA had a political wing, ], which split with ] at the same time as the split in the IRA, the early Provisional IRA was extremely suspicious of political activity, arguing rather for the primacy of armed struggle.<ref>Taylor, pp. 104–105.</ref> | |||

| ], which killed twenty-one people in November 1974<ref name="birmingham">{{harvnb|Oppenheimer|2008|pp=79–80.}}</ref>]] | |||

| ==Organisation== | |||

| On 22 June the IRA announced that a ceasefire would begin at midnight on 26 June, in anticipation of talks with the British government.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=157.}}</ref> Two days later Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill held a ] in Dublin to announce the ] (New Ireland) policy, which advocated an all-Ireland ] republic, with ] and parliaments for each of the four historic ].{{refn|group=n|The Army Council withdrew its support for Éire Nua in 1979.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=363.}}</ref> It remained ] policy until 1982.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=200–201.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=95.}}</ref><ref name="éirenua">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=181–182.}}</ref> This was designed to deal with the fears of unionists over a united Ireland, an ] parliament with a narrow Protestant majority would provide them with protection for their interests.<ref name="éirenua"/><ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|pp=126–127.}}</ref> The British government held secret talks with the republican leadership on 7 July, with Mac Stíofáin, Ó Conaill, ], Twomey, ], and ] flying to England to meet a British delegation led by ].<ref name="taylor1972">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=140–143.}}</ref> Mac Stíofáin made demands including British withdrawal, removal of the British Army from sensitive areas, and a release of republican prisoners and an amnesty for fugitives.<ref name="taylor1972"/> The British refused and the talks broke up, and the IRA's ceasefire ended on 9 July.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=158.}}</ref> In late 1972 and early 1973 the IRA's leadership was being depleted by arrests on both sides of the Irish border, with Mac Stíofáin, Ó Brádaigh and McGuinness all imprisoned for IRA membership.<ref name="taylorengland">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=152–153.}}</ref> Due to the crisis ] in March 1973, as the Army Council believed bombs in England would have a greater impact on British public opinion.<ref name="taylorengland"/><ref name="mcgladdery1970s">{{harvnb|McGladdery|2006|pp=59–61.}}</ref> This was followed by an intense period of IRA activity in England that left forty-five people dead by the end of 1974, including twenty-one civilians killed in the ].<ref name="birmingham"/><ref name="mcgladdery1970s"/> | |||

| The IRA is organised hierarchically. At the top of the organisation is the ], headed by the ]. | |||

| Following an IRA ceasefire over the Christmas period in 1974 and a further one in January 1975, on 8 February the IRA issued a statement suspending "offensive military action" from six o'clock the following day.<ref name="auto3">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=186.}}</ref><ref name="white1975a">{{harvnb|White|2017|pp=122–123.}}</ref> A series of meetings took place between the IRA's leadership and British government representatives throughout the year, with the IRA being led to believe this was the start of a process of British withdrawal.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=179.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=190–191.}}</ref> Occasional IRA violence occurred during the ceasefire, with bombs in Belfast, Derry, and South Armagh.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=132.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=135.}}</ref> The IRA was also involved in ] sectarian killings of Protestant civilians, in retaliation for sectarian killings by loyalist paramilitaries.<ref name="taylortruce">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=195–196.}}</ref><ref name="moloneyceasefire">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=144–147.}}</ref> By July the Army Council was concerned at the progress of the talks, concluding there was no prospect of a lasting peace without a public declaration by the British government of their intent to withdraw from Ireland.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=193–194.}}</ref> In August there was a gradual return to the armed campaign, and the truce effectively ended on 22 September when the IRA set off 22 bombs across Northern Ireland.<ref name="taylortruce"/><ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=136.}}</ref> The ] leadership of Ó Brádaigh, Ó Conaill, and McKee were criticised by a younger generation of activists following the ceasefire, and their influence in the IRA slowly declined.<ref>{{harvnb|Mallie|Bishop|1988|p=285.}}</ref><ref name="taylorng">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=197.}}</ref> The younger generation viewed the ceasefire as being disastrous for the IRA, causing the organisation irreparable damage and taking it close to being defeated.<ref name="taylorng"/> The Army Council was accused of falling into a trap that allowed the British breathing space and time to build up ] on the IRA, and McKee was criticised for allowing the IRA to become involved in sectarian killings, as well a feud with the Official IRA in October and November 1975 that left eleven people dead.<ref name="moloneyceasefire"/> | |||

| ===Leadership=== | |||

| All levels of the IRA are entitled to send delegates to IRA General Army Conventions (GACs). The GAC is the IRA's supreme decision-making authority. Before 1969, GACs met regularly. Since 1969 there have only been two, in 1970 and 1986, owing to the difficulty in organising such a large secret gathering of what is an illegal organisation.<ref name="structure">{{cite book | last = O'Brien | first = Brendan | authorlink = Brendan O'Brien (Irish journalist) | title = The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin | publisher = O'Brien Press |year=1999 | pages = 158 | doi = | isbn = 0-86278-606-1}}</ref><ref>English, pp. 114–115.</ref> | |||

| === The "Long War" === | |||

| The GAC in turn elects a 12-member ], which in turn selects seven volunteers to form the IRA Army Council.<ref name="structure"/> For day-to-day purposes authority is vested in the Army Council which, as well as directing policy and taking major tactical decisions, appoints a Chief of Staff from one of its number or, less commonly, from outside its ranks.<ref>English, p. 43</ref> | |||

| <!-- This section header has a redirect to ]; if the section head is altered, then alter the redirect. --> | |||

| {{See also|1981 Irish hunger strike|Armalite and ballot box strategy}} | |||

| ] written on the first day of the ]<ref>{{harvnb|Hennessy|2013|p=160.}}</ref>]] | |||

| Following the end of the ceasefire, the British government introduced a new three-part strategy to deal with the Troubles; the parts became known as ], normalisation, and criminalisation.<ref name="taylor202">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=202.}}</ref> Ulsterisation involved increasing the role of the locally recruited RUC and ] (UDR), a part-time element of the British Army, in order to try to contain the conflict inside Northern Ireland and reduce the number of British soldiers recruited from outside of Northern Ireland being killed.<ref name="taylor202"/><ref name="white124">{{harvnb|White|2017|p=124.}}</ref> Normalisation involved the ending of internment without trial and ], the latter had been introduced in 1972 following a hunger strike led by McKee.<ref name="white124"/><ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=193.}}</ref> Criminalisation was designed to alter public perception of the Troubles, from an insurgency requiring a military solution to a criminal problem requiring a law enforcement solution.<ref name="taylor202"/><ref>{{harvnb|Shanahan|2008|p=225.}}</ref> As result of the withdrawal of Special Category Status, in September 1976 IRA prisoner ] began the ] in the ], when hundreds of prisoners refused to wear prison uniforms.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|p=190.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=203–204.}}</ref> | |||

| The chief of staff then appoints an ] as well as a ], which consists of a number of individual departments. These departments are: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * IRA Director of Finance | |||

| * IRA Director of Engineering | |||

| * IRA Director of Training | |||

| * IRA Director of Intelligence | |||

| * IRA Director of Publicity | |||

| * IRA Director of Operations | |||

| * ] | |||

| In 1977 the IRA evolved a new strategy which they called the "Long War", which would remain their strategy for the rest of the Troubles.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=198.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=185–186.}}</ref> This strategy accepted that their campaign would last many years before being successful, and included increased emphasis on political activity through Sinn Féin.<ref name="taylorlw">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=214–215.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|pp=146–147.}}</ref> A republican document of the early 1980s states "Both Sinn Féin and the IRA play different but converging roles in the war of national liberation. The Irish Republican Army wages an armed campaign{{nbsp}}... Sinn Féin maintains the propaganda war and is the public and political voice of the movement".<ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=128.}}</ref> The 1977 edition of the '']'', an induction and training manual used by the IRA, describes the strategy of the "Long War" in these terms: | |||

| ===Regional command=== | |||

| At a regional level, the IRA is divided into a Northern Command, which operates in the nine Ulster counties as well as ] and ], and a ], operating in the rest of Ireland. The Provisional IRA was originally commanded by a leadership based in ]. However, in 1977, parallel to the introduction of cell structures at local level, command of the "war-zone" was given to the Northern Command. These moves at reorganisation were, according to ] the idea of ], ] and ].<ref>Moloney, pp. 155–160.</ref> | |||

| # A war of attrition against enemy personnel which is aimed at causing as many casualties and deaths as possible so as to create a demand from their people at home for their withdrawal. | |||

| ===Brigades=== | |||

| # A bombing campaign aimed at making the enemy's financial interests in our country unprofitable while at the same time curbing long-term investment in our country. | |||

| The IRA refers to its ordinary members as ] (or ''óglaigh'' in ]). Up until the late 1970s, IRA volunteers were organised in units based on conventional military structures. Volunteers living in one area formed a ], which in turn was part of a ], which could be part of a ], although many battalions were not attached to a brigade. | |||

| # To make the Six Counties{{nbsp}}... ungovernable except by colonial military rule. | |||

| # To sustain the war and gain support for its ends by National and International propaganda and publicity campaigns. | |||

| # By defending the war of liberation by punishing criminals, ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=23.}}</ref> | |||

| The "Long War" saw the IRA's tactics move away from the large bombing campaigns of the early 1970s, in favour of more attacks on members of the security forces.<ref name="smith">{{harvnb|Smith|1995|pp=155–157.}}</ref> The IRA's new multi-faceted strategy saw them begin to use ], using the publicity gained from attacks such as the assassination of ] and the ] to focus attention on the nationalist community's rejection of British rule.<ref name="smith"/> The IRA aimed to keep Northern Ireland unstable, which would frustrate the British objective of installing a ] government as a solution to the Troubles.<ref name="smith"/> | |||

| For most of its existence, the IRA had five Brigade areas within what it referred to as the "war-zone". These Brigades were located in Belfast, Derry, Tyrone/Monaghan and Armagh.<ref>O'Brien p. 158.</ref> The ] had three battalions, respectively in the west, north and east of the city. In the early years of ], the IRA in Belfast expanded rapidly. In August 1969, the Belfast Brigade had just 50 active members. By the end of 1971, it had 1,200 members, giving it a large but loosely controlled structure.<ref>Moloney, p. 103.</ref> ] city had one battalion and the ''South Derry Brigade''. The Derry Battalion became the Derry Brigade in 1972 after a rapid increase in membership following ] when British paratroopers killed 13 unarmed demonstrators at a civil rights march.<ref></ref> County Armagh had three battalions, two very active ones in South Armagh and a less active unit in North Armagh. For this reason the Armagh IRA unit is often referred to as the ]. Similarly, the Tyrone/Monaghan Brigade, which operated from around the Border, is often called the ]. Fermanagh, South Down, North Antrim had units not attached to Brigades.<ref>O'Brien, p. 161.</ref> The leadership structure at battalion and company level was the same: each had its own commanding officer, quartermaster, explosives officer and intelligence officer. There was sometimes a training officer or finance officer. | |||

| ], an assassination attempt on British prime minister ] in 1984<ref name="oppenheimerbrighton"/>]] | |||

| ===Active Service Units=== | |||

| In 1977, the IRA moved away from the larger conventional military organisational principle owing to its perceived security vulnerability. In place of the battalion structures, a system of two parallel types of unit within an IRA Brigade was introduced. Firstly, the old "company" structures were used for tasks such as "policing" nationalist areas, intelligence gathering, and hiding weapons. These were essential support activities. However, the bulk of actual attacks were the responsibility of a second type of unit, the ] (ASU). To improve security and operational capacity these ASUs were smaller, tight-knit cells, usually consisting of 5–8 members, for carrying out armed attacks. The ASU's weapons were controlled by a ] under the direct control of the IRA leadership.<ref>Bowyer Bell, p. 437.</ref> By the late 1980s and early 1990s, it was estimated that the IRA had roughly 300 members in ASUs and another 450 or so others serving in supporting roles.<ref>O'Brien, p. 161.</ref> | |||

| The prison protest against criminalisation culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three ] members starved themselves to death in pursuit of political status.<ref>{{harvnb|Sanders|2012|p=152.}}</ref> The hunger strike leader ] and ] activist ] were successively elected to the British ], and two other protesting prisoners were elected to Dáil Éireann.<ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=212–213.}}</ref> The electoral successes led to the IRA's armed campaign being pursued in parallel with increased electoral participation by Sinn Féin.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=281.}}</ref> This strategy was known as the "Armalite and ballot box strategy", named after ]'s speech at the 1981 Sinn Féin ard fheis: | |||

| The exception to this reorganisation was the ] which retained its traditional hierarchy and battalion structure and used relatively large numbers of volunteers in its actions.<ref>Moloney, p. 377.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>Who here really believes that we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in this hand we take power in Ireland?<ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=127.}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The IRA's Southern Command, located in the Republic of Ireland, consists of a Dublin Brigade and a number of smaller units in rural areas. These were charged mainly with the importation and storage of arms for the Northern units and with raising finance through robberies and other means.<ref>O'Brien, p. 158.</ref> They also maintained a sizable presence in North Kerry; where many training camps were based.{{Fact|date=October 2008}} | |||

| Attacks on high-profile political and military targets remained a priority for the IRA.<ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=184.}}</ref><ref name="mcgladdery">{{harvnb|McGladdery|2006|p=117.}}</ref> The ] in London in October 1981 killed two civilians and injured twenty-three soldiers; a week later the IRA struck again in London with an assassination attempt on Lieutenant General ], the ].<ref name="mcgladdery"/> Attacks on military targets in England continued with the ] in July 1982, which killed eleven soldiers and injured over fifty people including civilians.<ref>{{harvnb|McGladdery|2006|pp=119–120.}}</ref> In October 1984 they carried out the ], an assassination attempt on British prime minister ], whom they blamed for the deaths of the ten hunger strikers.<ref name="oppenheimerbrighton">{{harvnb|Oppenheimer|2008|pp=119–120.}}</ref> The bombing killed five members of the ] attending a party conference including MP ], with Thatcher narrowly escaping death.<ref name="oppenheimerbrighton"/><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=252–253.}}</ref> A planned escalation of the England bombing campaign in 1985 was prevented when six IRA volunteers, including ] and the Brighton bomber ], were arrested in Glasgow.<ref name="engdept">{{harvnb|Dillon|1996|pp=220–223.}}</ref> Plans for a major escalation of the campaign in the late 1980s were cancelled after a ship carrying 150 tonnes of weapons donated by Libya was seized off the coast of France.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=246.}}</ref> The plans, modelled on the ] during the ], relied on the element of surprise which was lost when the ship's captain informed French authorities of four earlier shipments of weapons, which allowed the British Army to deploy appropriate ]s.<ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=20–23.}}</ref> In 1987 the IRA began attacking British military targets in mainland Europe, beginning with the ], which was followed by approximately twenty other gun and bomb attacks aimed at ] personnel and bases between 1988 and 1990.<ref name="cooganeurope"/><ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=329.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Strategy 1969–1998== | |||

| {{seealso|Provisional IRA campaign 1969-1997}} | |||

| === Peace process === | |||

| ==="Escalation, escalation and escalation"=== | |||

| {{Main|Northern Ireland peace process}} | |||

| Following the violence of August 1969, the IRA began to arm and train to protect nationalist areas from further attack.<ref>{{cite book |title=From Civil Rights to Armalites |last=Ó Dochartaigh |first=Niall |year=2005 |publisher=Palgrave MacMillan |location= |isbn=1 4039 4431 8 |pages=162}}</ref> After the split, the Provisional IRA began planning for an "all-out offensive action against the British occupation."<ref>{{cite book |title=Memoirs of a Revolutionary |last=MacStiofáin |first=Seán |year=1979 |publisher=Free Ireland Book Club |pages=146}}</ref> | |||

| By the late 1980s the Troubles were at a military and political stalemate, with the IRA able to prevent the British government imposing a settlement but unable to force their objective of Irish reunification.<ref>{{harvnb|Leahy|2020|p=212.}}</ref> Sinn Féin president Adams was in contact with ] (SDLP) leader ] and a delegation representing the Irish government, in order to find political alternatives to the IRA's campaign.<ref>{{harvnb|Leahy|2020|pp=201–202.}}</ref> As a result of the republican leadership appearing interested in peace, British policy shifted when ], the ], began to engage with them hoping for a political settlement.<ref name="niall">{{harvnb|Ó Dochartaigh|2015|pp=210–211.}}</ref> ] between the IRA and British government began in October 1990, with Sinn Féin being given an advance copy of a planned speech by Brooke.<ref>{{harvnb|Dillon|1996|p=307.}}</ref> The speech was given in London the following month, with Brooke stating that the British government would not give in to violence but offering significant political change if violence stopped, ending his statement by saying: | |||

| The ] were opposed to such a campaign because it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The IRA ] in the 1950s had avoided actions in urban centres of Northern Ireland to avoid civilian casualties and resulting sectarian violence.<ref>Patrick Bishop, Eamon Mallie, The Provisional IRA, p. 40, "It aimed at destroying people rather than property and all units were under instruction to avoid civilian bloodshed. For this reason and because there were doubts about the Belfast IRA, which GHQ in Dublin to contain a traitor, there would be no action in the city".</ref> The Provisional IRA, by contrast was primarily an urban organisation, based originally in Belfast and Derry. | |||

| <blockquote>The British government has no selfish, strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland: Our role is to help, enable and encourage {{nbsp}}... Partition is an acknowledgement of reality, not an assertion of national self-interest.{{refn|group=n|Brooke's speech is known as the Whitbread Speech as it was given at the Whitbread Restaurant in London, in front of the British Association of Canned Food Importers & Distributors.<ref name="niall"/><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=317–318.}}</ref> It is regarded as a key moment in the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Feeney|2002|p=373.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|p=297.}}</ref>}}<ref name="o'brienbrooke">{{harvnb|O'Brien|1999|pp=209–212.}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use as much force as possible to cause the collapse of the Northern Ireland administration and to inflict enough casualties on the British forces that the British government would be forced by public opinion to withdraw from Ireland. According to journalist Brendan O'Brien, "the thinking was that the war would be short and successful. Chief of Staff Seán Mac Stíofáin decided they would "escalate, escalate and escalate" until the British agreed to go".<ref>O'Brien The Long War, p. 119.</ref> This policy involved intensive recruitment of volunteers and carrying out as many attacks on British forces as possible, as well as mounting a bombing campaign against economic targets. In the early years of the conflict, IRA slogans spoke of, "Victory 1972" and then "Victory 1974".<ref>O'Brien, Long War, p. 107.</ref> Its inspiration was the success of the "]" in the ] (1919–1922). In their assessment of the IRA campaign, the British Army would describe these years, 1970–72, as the "insurgency phase".<ref><!-- Bot generated title --></ref> | |||

| ]. The IRA's ] killed seven members of the security forces in ] in 1993.<ref>{{harvnb|Harnden|1999|p=290.}}</ref>]] | |||

| The British government held secret talks with the IRA leadership in 1972 to try and secure a ceasefire based on a compromise settlement within Northern Ireland after the events of ] when IRA recruitment and support increased. The IRA agreed to a temporary ceasefire from 26 June to 9 July. In July 1972, IRA leaders ], ], ], ], ] and ] met a British delegation led by ]. The IRA leaders refused to consider a peace settlement that did not include a commitment to British withdrawal, a retreat of the British Army to its barracks, and a release of republican prisoners. The British refused and the talks broke up.<ref>Taylor, p. 139.</ref> | |||

| The IRA responded to Brooke's speech by declaring a three-day ceasefire over Christmas, the first in fifteen years.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=320.}}</ref> Afterwards the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 36 bombs in 1991 and 57 in 1992, up from 15 in 1990.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=264.}}</ref> The ] in April 1992 killed three people and caused an estimated £800 million worth of damage, £200 million more than the total damage caused by the Troubles in Northern Ireland up to that point.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=266.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=327.}}</ref> In December 1992 ], who had succeeded Brooke as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, gave a speech directed at the IRA in ], stating that while Irish reunification could be achieved by negotiation, the British government would not give in to violence.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=328.}}</ref> The secret talks between the British government and the IRA via ] continued, with the British government arguing the IRA would be more likely to achieve its objective through politics than continued violence.{{refn|group=n|] and ] were used as intermediaries.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=263.}}</ref> The intermediary would receive messages from a British government representative either face-to-face or by using a safe telephone or ], and would forward the messages to the IRA leadership.<ref name="taylorpeace">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=329–331.}}</ref>}}<ref name="taylorpeace"/> The talks progressed slowly due to continued IRA violence, including the ] in March 1993 which killed two children and the ] a month later which killed one person and caused an estimated £1 billion worth of damage.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=332–335.}}</ref> In December 1993 a press conference was held at London's ] by British prime minister ] and the Irish Taoiseach ].<ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=412.}}</ref> They delivered the ] which conceded the right of Irish people to ], but with separate referendums in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.<ref>{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=342–343.}}</ref> In January 1994 The Army Council voted to reject the declaration, while Sinn Féin asked the British government to clarify certain aspects of the declaration.<ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=417–419.}}</ref> The British government replied saying the declaration spoke for itself, and refused to meet with Sinn Féin unless the IRA called a ceasefire.<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=273.}}</ref> | |||

| On 31 August 1994 the IRA announced a "complete cessation of military operations" on the understanding that Sinn Féin would be included in political talks for a settlement.<ref>{{harvnb|Tonge|2001|p=168.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Smith|1995|p=212.}}</ref> A new strategy known as "TUAS" was revealed to the IRA's rank-and-file following the ceasefire, described as either "Tactical Use of Armed Struggle" to the ] or "Totally Unarmed Strategy" to the broader Irish nationalist movement.<ref name="moloneytuas">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=423.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Leahy|2020|p=221.}}</ref> The strategy involved a coalition including Sinn Féin, the SDLP and the Irish government acting in concert to apply leverage to the British government, with the IRA's armed campaign starting and stopping as necessary, and an option to call off the ceasefire if negotiations failed.<ref name="moloneytuas"/> The British government refused to admit Sinn Féin to multi-party talks before the IRA ], and a standoff began as the IRA refused to disarm before a final peace settlement had been agreed.<ref name="taylorcf">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=349–350.}}</ref> The IRA regarded themselves as being undefeated and decommissioning as an act of surrender, and stated decommissioning had never been mentioned prior to the ceasefire being declared.<ref name="taylorcf"/> In March 1995 Mayhew set out three conditions for Sinn Féin being admitted to multi-party talks.<ref name="taylorcf"/> Firstly the IRA had to be willing to agree to "disarm progressively", secondly a scheme for decommissioning had to be agreed, and finally some weapons had to be decommissioned prior to the talks beginning as a ].<ref name="taylorcf"/> The IRA responded with public statements in September calling decommissioning an "unreasonable demand" and a "]" by the British government.<ref>{{harvnb|English|2003|pp=288–289.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Éire Nua and the 1975 ceasefire=== | |||

| The Provisionals' ultimate goal in this period was the abolition of both the Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland states and their replacement with a new all-Ireland ] republic, with decentralised governments and parliaments for each of the four Irish historic provinces. This programme was known as ] (''New Ireland''). The Éire Nua programme remained policy until discontinued by the Provisionals under the leadership of Gerry Adams in the early 1980s in favour of the pursuit of a new ] all-Ireland Republic. | |||

| ], which killed two people and ended the IRA's seventeen-month ceasefire<ref name="docklands">{{harvnb|Harnden|1999|pp=5–6.}}</ref>]] | |||

| By the mid 1970s, it was clear that the hopes of the IRA leadership for a quick military victory were receding. The ] military was equally unsure of when it would begin to see any substantial success against the IRA. Secret meetings between Provisional IRA leaders ] and ] with British ] ] secured an IRA ceasefire which began in February 1975. The IRA initially believed that this was the start of a long term process of British withdrawal, but later came to the conclusion that Rees was trying to bring them into peaceful politics without offering them any guarantees.<ref>{{cite book | last = Taylor | first = Peter | authorlink = Peter Taylor (Journalist) | title = Brits | publisher = ] |year=2001 | pages = 184–185 | doi = | isbn = 0-7475-5806-X}}</ref> Critics of the IRA leadership, most notably Gerry Adams, felt that the ceasefire was disastrous for the IRA, leading to infiltration by British informers, the arrest of many activists and a breakdown in IRA discipline resulting in ] and a feud with fellow republicans in the ]. The ceasefire broke down in January 1976.<ref name="Taylor p156">Taylor, p. 156.</ref> | |||

| On 9 February 1996 a statement from the Army Council was delivered to the Irish national broadcaster ] announcing the end of the ceasefire, and just over 90 minutes later the ] killed two people and caused an estimated £100–150 million damage to some of London's more expensive ].<ref name="docklands"/><ref>{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=441.}}</ref> Three weeks later the British and Irish governments issued a joint statement announcing multi-party talks would begin on 10 June, with Sinn Féin excluded unless the IRA called a new ceasefire.<ref name="taylor1996">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|pp=352–353.}}</ref> The IRA's campaign continued with the ] on 15 June, which injured over 200 people and caused an estimated £400 million of damage to the city centre.<ref>{{harvnb|McGladdery|2006|p=203.}}</ref> Attacks were mostly in England apart from the ] on a British Army base in Germany.<ref name="taylor1996"/><ref>{{harvnb|Ackerman|2016|p=33.}}</ref> The IRA's first attack in Northern Ireland since the end of the ceasefire was not until October 1996, when the ] killed a British soldier.<ref name="auto">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|p=444.}}</ref> In February 1997 an ] killed ] Stephen Restorick, the last British soldier to be killed by the IRA.<ref>{{harvnb|Harnden|1999|p=283.}}</ref> | |||

| Following the ] Major was replaced as prime minister by ] of the ].<ref name="moloney1997">{{harvnb|Moloney|2007|pp=457–458.}}</ref> The new Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, ], had announced prior to the election she would be willing to include Sinn Féin in multi-party talks without prior decommissioning of weapons within two months of an IRA ceasefire.<ref name="moloney1997"/> After the IRA declared a new ceasefire in July 1997, Sinn Féin was admitted into multi-party talks, which produced the ] in April 1998.<ref name="taylor354">{{harvnb|Taylor|1998|p=354.}}</ref><ref name="english297">{{harvnb|English|2003|p=297.}}</ref> One aim of the agreement was that all paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland fully disarm by May 2000.<ref>{{harvnb|Cox|Guelke|Stephen|2006|pp=113–114.}}</ref> The IRA began decommissioning in a process that was monitored by Canadian General ]'s ] (IICD),<ref>{{harvnb|Rowan|2003|pp=36–37.}}</ref> with some weapons being decommissioned on 23 October 2001 and 8 April 2002.<ref>{{harvnb|Cox|Guelke|Stephen|2006|p=165.}}</ref> The October 2001 decommissioning was the first time an Irish republican paramilitary organisation had voluntarily disposed of its arms.{{refn|group=n|After its defeat in the ] in 1923 and at the end of the unsuccessful ] in 1962, the ] issued orders to retain weapons, and the ] also retained its weapons following its 1972 ceasefire.<ref name="boyne403">{{harvnb|Boyne|2006|pp=403–404.}}</ref>}}<ref name="boyne403"/> In October 2002 the devolved ] was suspended by the British government and direct rule returned, in order to prevent a unionist walkout.{{refn|group=n|The assembly remained suspended until May 2007, when ] of the ] and ] of ] became ].<ref>{{harvnb|White|2017|p=364.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|Rowan|2003|p=27.}}</ref> This was partly triggered by ]—allegations that republican spies were operating within the ] and the ] (PSNI){{refn|group=n|In 2001 the ] was reformed and renamed the Police Service of Northern Ireland as a result of the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Cox|Guelke|Stephen|2006|p=115.}}</ref>}}<ref>{{harvnb|Rowan|2003|pp=15–16.}}</ref>—and the IRA temporarily broke off contact with de Chastelain.<ref>{{harvnb|Rowan|2003|p=30.}}</ref> However, further decommissioning took place on 21 October 2003.<ref>{{harvnb|Boyne|2006|p=405.}}</ref> In the aftermath of the December 2004 ], the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform ] stated there could be no place in government in either Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland for a party that supported or threatened the use of violence, possessed explosives or firearms, and was involved in criminality.<ref name="boyne">{{harvnb|Boyne|2006|pp=406–407.}}</ref> At the beginning of February 2005, the IRA declared that it was withdrawing a decommissioning offer from late 2004.<ref name="boyne"/> This followed a demand from the ], under Paisley, insisting on photographic evidence of decommissioning.<ref name="boyne"/> | |||

| ===The "Long War"===<!--this section header has a redirect to ] if the section head alters then alter the redirect--> | |||

| ] | |||

| Thereafter, the IRA, under the leadership of Adams and his supporters, evolved a new strategy termed the "Long War", which underpinned IRA strategy for the rest of the Troubles. It involved a re-organisation of the IRA into small ], an acceptance that their campaign would last many years before being successful and an increased emphasis on political activity through the ] party. A republican document of the early 1980s states, "Both Sinn Féin and the IRA play different but converging roles in the war of national liberation. The Irish Republican Army wages an armed campaign... Sinn Féin maintains the propaganda war and is the public and political voice of the movement".<ref>O'Brien, p. 128.</ref> The 1977 edition of the ], an induction and training manual used by the Provisionals, describes the strategy of the "Long War" in these terms: | |||

| <!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: ] --> | |||

| # A ] against enemy personnel based on causing as many deaths as possible so as to create a demand from their people at home for their withdrawal. | |||

| # A bombing campaign aimed at making the enemy's financial interests in our country unprofitable while at the same time curbing long term investment in our country. | |||

| # To make the Six Counties... ungovernable except by colonial military rule. | |||

| # To sustain the war and gain support for its ends by National and International propaganda and publicity campaigns. | |||

| # By defending the war of liberation by punishing criminals, collaborators and informers.<ref>O'Brien, p. 23.</ref> | |||

| However, the IRA leadership may also having been considering ways to end the conflict in the late 1970s. Newly released (December 30 2008) confidential documents from the British state archives show that the IRA leadership proposed a ceasefire and peace talks to the British government in 1978. The British refused the offer. Prime Minister ] decided that there should be "positive rejection" of the approach on the basis that the republicans were not serious and "see their campaign as a long haul". Irish State documents from the same period say that the IRA had made a similar offer to the British the previous year. An ] document, dated February 15th, 1977, states that, "It is now known that feelers were sent out at Christmas by the top PIRA leadership to interest the British authorities in another long ceasefire."<ref>http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/frontpage/2008/1230/1230581469072.html?via=mr</ref> | |||

| ===1981 hunger strikes and electoral politics=== | |||

| IRA prisoners convicted after March 1976 did not have ] applied in prison. In response, over 500 prisoners refused to wash or wear prison clothes (see ] and ].) This activity culminated in the ], when seven IRA and three ] members starved themselves to death in pursuit of political status. The hunger strike leader ] and ] activist ] were elected to the ], and two other protesting prisoners were elected to the Irish ]. In addition, there were work stoppages and large demonstrations all over Ireland in sympathy with the hunger strikers. Over 100,000 people attended the funeral of Sands, the first hunger striker to die. | |||

| After the success of IRA hunger strikers in mobilising support and winning elections on an ] platform in 1981, republicans increasingly devoted time and resources to electoral politics, through the Sinn Féin party. ] summed up this policy at a 1981 Sinn Féin ] (annual meeting) as a "ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other".<ref>O'Brien, p. 127.</ref> (See ]) | |||

| ==="TUAS" – peace strategy=== | |||

| In the 1980s, the IRA made an attempt to escalate the conflict with the so called "]". When this did not prove successful, republican leaders increasingly looked for a political compromise to end the conflict. Gerry Adams entered talks with ], the leader of the moderate nationalist ] (SDLP) and secret talks were also conducted with British civil servants. Thereafter, Adams increasingly tried to disassociate Sinn Féin from the IRA, claiming they were separate organisations and refusing to comment on IRA actions. Within the ] (the IRA and Sinn Féin), the new strategy was described by the acronym "TUAS", meaning either "Tactical Use of Armed Struggle" or "Totally Unarmed Strategy".<ref>Moloney, p. 432.</ref> | |||

| The IRA ultimately called an indefinite ceasefire in 1994 on the understanding that ] would be included in political talks for a settlement. When this did not happen, the IRA called off its ceasefire from February 1996 until July 1997, carrying out several bombing and shooting attacks. After its ceasefire was reinstated, Sinn Féin was admitted into the "Peace Process", which produced the ] of 1998. | |||

| ==Weaponry and operations== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{mainarticle|Provisional IRA arms importation|Provisional IRA campaign 1969-1997|Chronology of Provisional IRA Actions}} | |||

| <!-- Editors, Please do not expand this section as the article is already too big. Please go to the main articles to add further information --> | |||

| In the early days of ] from around 1969–71, the Provisional IRA was very poorly armed, but starting in the early 1970s it procured large amounts of modern weaponry from such sources as supporters in the ], ]n leader Colonel ],<ref name="Taylor p156"/> arms dealers in Europe, America, the ] and elsewhere. | |||

| In the first years of the conflict, the Provisionals' main activities were providing firepower to support nationalist rioters and defending nationalist areas from attacks. The IRA gained much of its support from these activities, as they were widely perceived within the nationalist community as being defenders of ] and ] people against aggression.<ref>English, pp. 134–135.</ref> | |||

| However, from 1971–1994, the Provisionals launched a sustained offensive armed campaign that mainly targeted the British Army, the ] (RUC), the ] (UDR), and economic targets in Northern Ireland. The first half of the 1970s was the most intense period of the IRA campaign. In addition, IRA units carried out ] killings such as the ] of 1976, which in itself was a retaliation for a Loyalist massacre of an entire Catholic family earlier in the same week. | |||

| ], obtained by the IRA from the ] in the early 1970s and an emotive symbol of its armed campaign]] | |||

| ] assault rifle (over 1,000 of which were donated by ] to the IRA in the 1980s)]] | |||

| The IRA was chiefly active in Northern Ireland, although it took its campaign to ], and also carried out attacks in the ], the ] and ]. The IRA also targeted certain British government officials, politicians, judges, senior military and police officers in ], and in other areas such as ] and the ]. By the early 1990s, the bulk of the IRA activity was carried out by the South Armagh Brigade, well known through its ] and attacks on British Army helicopters. The bombing campaign principally targeted political, economic and military targets, and approximately 60 civilians were killed by the IRA in England during the conflict.<ref>{{cite web | title = Crosstabulations (two-way tables) | author = | url = http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/crosstabs.html | publisher = '']'' | date = | accessdate = 2007-03-17}}</ref> It has been argued that this bombing campaign helped convince the British government (who had hoped to contain the conflict to Northern Ireland with its ] policy) to negotiate with ] after the IRA ceasefires of August 1994 and July 1997. | |||

| ===Ceasefires and decommissioning of arms=== | |||