| Revision as of 22:52, 18 April 2009 editVolunteer Marek (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers94,171 edits rvt naming guidelines violations - and if you want to change pic, get consensus. Also sign in← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:54, 1 January 2025 edit undoXTheBedrockX (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users83,636 edits added Category:Ostróda County using HotCat | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1410 battle between the Teutonic Order and Poland–Lithuania}} | |||

| {{For|the World War I battle at the same location|Battle of Tannenberg (1914)}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{For|the painting by Jan Matejko|Battle of Grunwald (painting)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2018}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=June 2008}} | |||

| | conflict = Battle of Grunwald | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |conflict=Battle of Grunwald | |||

| | image = Matejko Battle of Grunwald.jpg | |||

| |partof=the ] | |||

| | image_size = 300 | |||

| |image=] | |||

| | map_type = Poland | |||

| |caption=''Battle of Grunwald'', by ], 1878. Oil on canvas. | |||

| | map_relief = yes | |||

| |date=15 July 1410 | |||

| | map_marksize = 20 | |||

| |place=Between ] (Grünfelde)and ] (Tannenberg), ] | |||

| | map_mark = Big battle symbol.svg | |||

| |result=Decisive Polish-Lithuanian-Russian victory | |||

| | map_caption = Battle site on a map of modern Poland | |||

| |combatant1=] ]<ref name=Turnbul25>], ''Tannenberg 1410 Disaster for the Teutonic Knights'', 2003, London: Osprey Campaign Series no. 122 ISBN 9781841765617, </ref><br/>] ]<br>Polish-Lithuanian vassals, allies and mercenaries:<ref name=Turnbul26/><br/>{{flagicon|Moldavia}} ]<ref>Britannica Hungarica, Hungarian encyclopedia, 1994. ISBN 963062F3506</ref><br> ]<ref name=Turnbul25/> ]<ref name=Turnbul26/>, ]<ref name=Turnbul26/> ]<ref name=Turnbul27>], ''Tannenberg 1410 Disaster for the Teutonic Knights'', 2003, London: Osprey Campaign Series no. 122 ISBN 9781841765617, pp.27-28</ref> | |||

| | caption = '']'' by ] (1878) | |||

| |combatant2=] ] and mercenaries and various knights from the rest of Europe | |||

| | date = {{Start date|1410|07|15|df=yes}} | |||

| |commander1=] ] (Władysław II Jagiełło), supreme commander of the allied host<ref name=Turnbul26>], ''Tannenberg 1410 Disaster for the Teutonic Knights'', 2003, London: Osprey Campaign Series no. 122 ISBN 9781841765617, pp.26</ref><br> | |||

| | place = Between villages of ] (Grünfelde) and ] (Ludwigsdorf), western ], ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|53|29|10|N|20|07|29|E|type:event_region:PL|display=title}} | |||

| ] ], commander of the Lithuanian army | |||

| | result = Polish–Lithuanian victory | |||

| | combatant1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| ] commander of the Russian banners from Smolensk, | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ], Tatar commander, exiled Khan of the Golden horde<ref name=Turnbul26/> | |||

| '''Vassals, allies and mercenaries:''' | |||

| |commander2=] ]† | |||

| * ]{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ]† Grand Marshal | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ]† Grand Komtur | |||

| * ]{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=138}} | |||

| |strength1=39,000 men<ref name=Turnbul25/> | |||

| * ]{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} | |||

| |strength2=27,000 men<ref name=Turnbul25/> | |||

| * ] from ]{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=28}} | |||

| |casualties1=Unknown (relatively light) | |||

| * ]{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} | |||

| |casualties2=8,000 dead<br>14,000 captured | |||

| * ]{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} | |||

| * ]ns{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} | |||

| * ]ns{{sfn|Davies|2005|p=98}}}} | |||

| | combatant2 = {{plainlist|]<br> | |||

| '''Vassals, allies and mercenaries:''' | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] from ]}} | |||

| | commander1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * King ], supreme commander{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} | |||

| * Grand Duke ], Lithuanian commander | |||

| * Khan ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander2 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * Grand Master ]{{KIA}} | |||

| * Grand Marshal Friedrich von Wallenrode{{KIA}} | |||

| * Kuno von Lichtenstein {{KIA}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength1 = 16,000–39,000 men{{sfn|Jučas|2009|pp=57–58}} | |||

| | strength2 = 11,000–27,000 men{{sfn|Jučas|2009|pp=57–58}} | |||

| | casualties1 = Unknown; see ] | |||

| | casualties2 = 203–211 out of 270 brothers killed{{sfn|Frost|2015|pp=106–107}} <br/> See ] | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War}} | |||

| | territory = Decline of ]{{sfn|Gumilev|2024|p=292}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Grunwald''' |

The '''Battle of Grunwald'''{{efn|translated into ] as '''Battle of Žalgiris''', or translated into ] as '''First Battle of Tannenberg''',}} was fought on 15 July 1410 during the ]. The alliance of the ] and the ], led respectively by King ] (Jogaila), and Grand Duke ], decisively defeated the German ], led by Grand Master ]. Most of the Teutonic Order's leadership was killed or taken prisoner. | ||

| Although defeated, the Teutonic Order withstood the ] of the ] and suffered minimal territorial losses at the ], with other territorial disputes continuing until the ] in 1422. The order, however, never recovered their former power, and the financial burden of ] caused internal conflicts and an economic downturn in the lands controlled by them. The battle shifted the ] in ] and ] and marked the rise of the ] as the dominant regional political and military force.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=175}} | |||

| The battle saw the forces of the ] decisively defeated, but they defended their castles and retained most of its territories. The order never recovered its former power, and the financial burden of ensuing reparations decades later caused a rebellion of cities and landed gentry. | |||

| The battle was one of the largest in ].{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=92}} The battle is viewed as one of the most important victories in the histories of Poland and Lithuania. It is also commemorated in Ukraine and Belarus. For centuries, it has been re-interpreted in that part of Europe as an inspiration of ] (to advance legends or mythology) and national pride, becoming a larger symbol of struggle against foreign invaders.{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=43}} During the 20th century, the battle was used in ] and ] campaigns before and during World War II. Only in ] decades have historians moved towards a dispassionate, scholarly assessment of the battle, reconciling the previous narratives, which differed widely by nation.{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=44}} | |||

| The few eyewitness accounts are contradictory. It took place between three small villages, and different names in various languages are attributed to it. | |||

| == Names and |

== Names and sources == | ||

| === Names === | |||

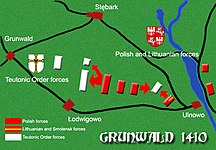

| The battle was fought in territory of the ], in the plains between <ref>Detailed old German maps at bildarchiv-ostpreussen.de </ref> the three small villages ] to the West, ] to the North East, and ] to the South. The Polish king referred to the site in a letter written in Latin as ''in loco conflictus nostri, quem cum Cruciferis de Prusia habuimus, dicto Grunenvelt''<ref>''On 16 September ... the Polish King made his intentions clear in a letter to the ] to have a Brigittine cloister and church built on the battlefield at Grünfelde, literally <tt>in loco conflictus nostri, quem cum Cruciferis de Prusia habuimus, dicto Grunenvelt.</tt>'' - Sven Ekdahl : ''The Battle of Tannenberg-Grunwald-Žalgiris (1410) as reflected in Twentieth-Century monuments'', , in: Victor Mallia-Milanes, Malcolm Barber et. al.: ''The Military Orders Volume 3: History and Heritage'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008 ISBN 075466290X 9780754662907 </ref> which by later Polish chroniclers was interpreted as Grunwald, meaning green wood or forest in German. This was rendered in the Lithuanian as ''Žalgiris''. The Germans had their troops deployed at Tannenberg (Stębark) (pine hill) and named the battle accordingly. | |||

| ] | |||

| Traditionally, the battle's location was thought to be in the territory of the ], on the plains between three villages: Grünfelde (]) to the west, Tannenberg (]) to the northeast and Ludwigsdorf (], Ludwikowice) to the south. However, research by Swedish historian {{ill|Sven Ekdahl|de}} and archaeological excavations in 2014–2017 proved that the actual site was south of Grünfelde (Grunwald).{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018}} Władysław II Jagiełło referred to the site in Latin as ''in loco conflictus nostri, quem cum Cruciferis de Prusia habuimus, dicto Grunenvelt''.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=175}} Later, Polish chroniclers interpreted the word ''Grunenvelt'' ("green field" in ]) as ''Grünwald'', meaning "green forest" in German. The Lithuanians followed suit and translated the name as ''Žalgiris''.{{sfn|Sužiedėlis|2011|p=123}} The name Žalgiris was first used by ] in 1891.{{sfn|Balčiūnas|2020}} The Germans named the battle after Tannenberg ("fir hill" or "pine hill" in German).{{sfn|Evans|1970|p=3}} Thus, there are three commonly used names for the battle: {{langx|de|Schlacht bei Tannenberg}}, {{langx|pl|bitwa pod Grunwaldem}}, {{langx|lt|Žalgirio mūšis}}. Its names in the languages of other involved peoples include {{langx|be|Бітва пад Грунвальдам}}, {{langx|uk|Грюнвальдська битва}}, {{langx|ru|Грюнвальдская битва}}, {{langx|cs|Bitva u Grunvaldu}}, {{langx|ro|Bătălia de la Grünwald}}. | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| Thus, for half a millenium, the battle was referred to as | |||

| There are few contemporary, reliable sources about the battle, and most were produced by the Polish. The most important and trustworthy source is ''Cronica conflictus Wladislai regis Poloniae cum Cruciferis anno Christi 1410'', which was written within a year of the battle by an eyewitness.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=8}} Its authorship is uncertain, but several candidates have been proposed: Polish ] ] and ]'s secretary ].{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=9}} While the original ''Cronica conflictus'' did not survive, a short summary from the 16th century has been preserved. ''Historiae Polonicae'' by Polish historian ] (1415–1480).{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=9}} is a comprehensive and detailed account written several decades after the battle. The reliability of this source suffers not only from the long gap since the events, but also from Długosz's alleged biases against Lithuanians.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=10}} '']'' is a mid-15th-century manuscript with images and Latin descriptions of the Teutonic ] captured during the battle and displayed in ] and ]s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Długosz |first1=Jan |authorlink1=Jan Długosz |title=Banderia Prutenorum |date=1448 |publisher=] |url=https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/239181/edition/227556/content |language=Latin |access-date=21 September 2021}}</ref> Other Polish sources include two letters written by Władysław II Jagiełło to his wife ] and ] ] and letters sent by Jastrzębiec to Poles in the ].{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=10}} German sources include a concise account in the chronicle of ]. An anonymous letter, discovered in 1963 and written between 1411 and 1413, provided important details on Lithuanian maneuvers.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=11}}{{sfn|Ekdahl|1963}} | |||

| *''Schlacht bei Tannenberg'' (''Battle near Tannenberg'') by ] | |||

| *''Bitwa pod Grunwaldem'' (''Battle of Grunwald'') by ] | |||

| *''Žalgirio mūšis'' (''Battle of Žalgiris'') by ] | |||

| == Historical background == | |||

| In languages of other involved nations the battle is called: {{lang-be|''Гру́нвальдзкая бі́тва''}}, ''Hrúnvaldzkaja bі́tva'', {{lang-uk|''Ґрю́нвальдська би́тва''}}, ''Gryúnvaldska býtva'', {{lang-ru|''Грю́нвальдская би́тва''}}, ''Gryúnvaldskaya bі́tva'', {{lang-tt|''Grünwald suğışı''}}, {{lang-cs|Bitva u Grunvaldu}}, {{lang-ro|Bătălia de la Grünwald}}. | |||

| === Lithuanian Crusade and Polish–Lithuanian union === | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main article|Lithuanian Crusade}} | |||

| In 1230, the ], a crusading ], moved to ] (Kulmerland) and launched the ] against the ] ]. With support from the pope and ], the Teutons conquered and converted the Prussians by the 1280s and shifted their attention to the pagan ]. For about 100 years, the order raided Lithuanian lands, particularly ], as it separated the order in Prussia from their ]. While the border regions became an uninhabited wilderness, the order gained very little territory. The Lithuanians first gave up Samogitia during the ] in the ].{{sfn|Kiaupa|Kiaupienė|Kuncevičius|2000}}{{pn|date=January 2024}} | |||

| == Background == | |||

| In the 13th century, the ], subject directly to the Pope, had been requested by ] to come to the lands surrounding ] (Chełmno) to assist in the Crusade against the ] ]. The Teutonic Order received the territory of Prussia via ]s from the ] and ] edict, which gave them effective ''carte blanche'' as owners of a new Christianized state of Prussia, instead of the pagan native land of Terra Prussiae. They later received the territory of further north ] coastal regions of what are now ], ] and ], and showed every sign of further expansion. | |||

| In 1385, Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania agreed to marry Queen ] in the ]. Jogaila converted to Christianity and was crowned King of Poland and became known as Władysław II Jagiełło, thus creating a ] between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The official ] removed the religious rationale for the order's activities in the area.{{sfn|Stone|2001|p=16}} Its grand master, ], supported by Hungarian King ], responded by publicly contesting the sincerity of Jogaila's conversion, bringing the charge to a ].{{sfn|Stone|2001|p=16}} The territorial disputes continued over Samogitia, which had been in Teutonic hands since the ] in 1404. Poland also had territorial claims against the order in ] and Gdańsk (]), but the two states had been largely at peace since the ].{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=132}} The conflict was also motivated by trade considerations: the order controlled the lower reaches of the three largest rivers (the ], ] and ]) in Poland and Lithuania.{{sfn|Kiaupa|Kiaupienė|Kuncevičius|2000|p=137}} | |||

| In 1385 the ] joined the crown of Poland and Lithuania, and the subsequent marriage of ] and reigning Queen ] was to shift the balance of power; both nations were more than aware that only by acting together could the expansionist plans of the Teutonic Order be thwarted. Jogaila accepted Christianity and became the King of Poland as ]. Lithuania's conversion to Christianity removed much of the rationale of the Teutonic Knights' anti-pagan crusades. It can be said the ] lost its ''raison d'etre''. | |||

| === War, truce and preparations === | |||

| In 1409, an ] started. The king of Poland and ] announced that he would stand by his promises in case the knights invaded Lithuania. This was used as a pretext, and on 14 August 1409 the Teutonic Grand Master ] declared war on the ] and ]. The forces of the Teutonic Order initially invaded ] and ], but the Poles repelled the invasion and reconquered ] (Bromberg), which led to a subsequent ] agreement that was to last until 24 June 1410. The Lithuanians and Poles used this time for preparations to remove the Teutonic threat once and for all. | |||

| ] between 1260 and 1410; the locations and dates of major battles, including the Battle of Grunwald, are indicated by crossed red swords.]] | |||

| ] fighting with Teutonic knights (14th-century ] from the ])]] | |||

| In May 1409, an ] started. Lithuania supported it and the order threatened to invade. Poland announced its support for the Lithuanian cause and threatened to invade Prussia in return. As Prussian troops evacuated Samogitia, Teutonic Grand Master ] declared war on the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on 6 August 1409.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=20}} The order hoped to defeat Poland and Lithuania separately, and began by invading ] and ], catching the Poles by surprise.{{sfn|Ivinskis|1978|p=336}} The order burned the castle at Dobrin (]), captured ] after a 14-day siege, conquered ] (Bromberg) and sacked several towns.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=130}} The Poles organized counterattacks and recaptured Bydgoszcz.{{sfn|Kuczynski|1960|p=614}} The Samogitians attacked Memel (]).{{sfn|Ivinskis|1978|p=336}} However, neither side was ready for a full-scale war. | |||

| ==Military preparation== | |||

| The forces of the Teutonic Knights were aware of the Polish-Lithuanian build-up and expected a dual attack, by the Poles towards Danzig (]) and by the Lithuanians towards ]. To counter this threat, Ulrich von Jungingen concentrated part of his forces in Schwetz (]) while leaving the large part of his army in the eastern castles of Ragnit (], Rhein (]) near Lötzen (]), and Memel (]). Poles and Lithuanians continued to screen their intentions by organising several raids deep into enemy territory. Ulrich von Jungingen asked for the armistice to be extended to July 4 in order to let the ] from western Europe arrive. Enough time had already been given for the Polish-Lithuanian forces to gather in strength. | |||

| ], agreed to mediate the dispute. A truce was signed on 8 October 1409 and was set to expire on 24 June 1410.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=51}} Both sides used this time to prepare for war, gathering troops and engaging in diplomatic maneuvering. Both sides sent letters and envoys accusing each other of various wrongdoings and threats to the Christendom. Wenceslaus, who received a gift of 60,000 florins from the order, declared that Samogitia rightfully belonged to the order and only Dobrzyń Land should be returned to Poland.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=21}} The order also paid 300,000 ]s to ], who had ambitions regarding the ], for mutual military assistance.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=21}} Sigismund attempted to break the Polish–Lithuanian alliance by offering Vytautas a king's crown; Vytautas' acceptance would have violated the terms of the ] and created Polish-Lithuanian discord.{{sfn|Kiaupa|Kiaupienė|Kuncevičius|2000|p=139}} At the same time, Vytautas managed to obtain a truce from the ].{{sfn|Christiansen|1997|p=227}} | |||

| On 30 June 1410, the forces of Greater Poland and ] crossed the ] over a ] and joined with the forces of ] and the ]. Jogaila's Polish forces and the Lithuanian soldiers of his cousin ] ] (to whom Jogaila had ceded power in Lithuania in the wake of his marriage to the Polish queen) assembled on 2 July 1410. A week later they crossed into the territory of the Teutonic Knights, heading for the enemy headquarters at the castle of Marienburg (]). The Teutonic Knights were caught by surprise. | |||

| By December 1409, Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas had agreed on a common strategy: their armies would unite into a single massive force and march together towards Marienburg (]), capital of the Teutonic Order.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=30}} The order, who took a defensive position, did not expect a joint attack and were preparing for a dual invasion—by the Poles along the ] towards Danzig (]) and the Lithuanians along the ] towards Ragnit (]).{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} To counter this perceived threat, Ulrich von Jungingen concentrated his forces in Schwetz (]), a central location from where troops could respond to an invasion from any direction rather quickly.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=74}} Sizable garrisons were left in the eastern castles of Ragnit, Rhein (]) near Lötzen (]) and Memel (]).{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} To keep their plans secret and mislead the order, Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas organized several raids into border territories, thus forcing the order to keep their troops in place.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=30}} | |||

| Ulrich von Jungingen withdrew his forces from the area of Schwetz (]) and decided to organise a line of defence on the river Drewenz (]). The river crossings were fortified with ]s and the castles nearby reinforced. After meeting with his War Council, Jogaila decided to outflank the enemy forces from the East and on his attack on Prussia he continued the march towards Marienburg through Soldau (]) and Neidenburg. The towns were heavily damaged and Gilgenburg was completely plundered and burned to the ground, causing many refugees. On 13 July the two castles were captured and the way towards Marienburg was opened. | |||

| == Opposing forces == | == Opposing forces == | ||

| {{Further|List of banners in the Battle of Grunwald}} | |||

| In the early morning of 15 July 1410, both armies met in the fields near the villages of ], Stębark (]) and ] (Ludwigsdorf). Both armies were formed in opposing lines. The Polish-Lithuanian army was positioned in front and East of the villages of Ludwigsdorf and Tannenberg. The left flank was guarded by the ] forces of king ] and composed mostly of heavy cavalry. The right flank of the allied forces was guarded by the army of Grand Duke ], and composed mostly of light cavalry. Among the forces on the right flank were banners from all over the ], as well as ] skirmishers under ], ] ] sent by ] and allegedly ].{{Fact|date=June 2008}} The opposing forces of the ] were composed mostly of heavy cavalry and infantry. They were to be aided by troops from Western Europe called "the guests of the Order", who were still on the way, and other Knights who had been summoned to participate by a ].{{Fact|date=June 2008}} | |||

| <!-- SORTED FROM SMALLEST TOTAL TO LARGEST TOTAL TROOPS --> | |||

| {| class="wikitable floatright" | |||

| The exact number of soldiers on both sides is hard to estimate.<ref name=Turnbul25/> There are only two reliable sources describing the battle.{{Fact|date=June 2008}} The best-preserved and most complete account, ], was written by ], but does not mention the exact numbers. The other is an incomplete and preserved only in a brief 16th century document.{{Who|date=June 2008}} Months after the battle, in December 1410, the Order's new Grand Master ] sent letters to Western European monarchs in which he described the battle as a war against the forces of evil pagans. This view was shared by many chronicle writers. Since the outcome of the battle was subject to propaganda campaigns on both sides, many foreign authors frequently overestimated the Polish-Lithuanian forces in an attempt to explain the dramatic result. | |||

| |+ Various estimates of opposing forces{{sfn|Jučas|2009|pp=57–58}} | |||

| In one of the Prussian chronicles it is mentioned that "''the forces of the Polish king were so numerous that there is no number high enough in the human language''". One of the anonymous chronicles from the German ] city of ] mentions that the forces of Jogaila numbered some 1,700,000 soldiers, the forces of Vytautas with 2,700,000 (with ''a great number of ], or ], as they were called then''), in addition to 1,500,000 Tatars.{{Fact|date=June 2008}} Among the forces supposedly aiding the Polish-Lithuanian army were "''], ], pagans of ], ] and other lands''".{{Fact|date=June 2008}} According to ], the knights fielded some 300,000 men, while their enemies under the kings of "''Lithuania, Poland and ]''" fielded 600,000. ] estimated the Polish-Lithuanian forces at 1,200,000 men-at-arms. It must be noted that medieval chroniclers were notorious for sensationally inflating figures, and armies of the sizes quoted were actually impossible with the logistics technology of the day. | |||

| More recent historians estimate the strength of the opposing forces at a much lower level. ] estimated the Polish-Lithuanian forces at 16,000-18,000 Polish cavalry and 6,000-8,000 Lithuanian light cavalry, with the Teutonic Knights fielding 13,000-15,000 heavy cavalry. ] estimated the overall strength of the allied forces at 18,000 Polish cavalry and 11,000 Lithuanians and Ruthenians, with the opposing forces bringing 16,000 soldiers. If these figures are accepted, this would make the battle less well attended than the ] fought in Yorkshire, England, in the same century, which engaged two armies of around 40,000 men, 28,000 of whom died. | |||

| <!--SCROLL DOWN TO EDIT THE ARTICLE--> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! Historian | |||

| ! Poland | |||

| ! Lithuania | |||

| ! Others | |||

| ! Teutonic Order | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Historian || Polish || Lithuanian || Teutonic | |||

| | ] Chronicle | |||

| | 1.700,000 | |||

| | 2.700,000 | |||

| | 1.500,000 | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] and<br/> ]{{sfn|Frost|2015|p=106}} || 10,500 || 6,000 || 11,000 <!---- TOTAL: 27.5 ----> | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 600.000 | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | 300.000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ]{{sfn|Разин|1999|p=486}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 16,000–17,000 || 11,000 <!---- TOTAL: 28 ----> | |||

| | 1.200.000 | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | | ] | ||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 23,000 || 15,000 <!---- TOTAL: 38 ----> | |||

| | 18.000 heavy cavalry | |||

| | 8.000 light cavalry | |||

| | | |||

| | 15.000 heavy cavalry | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| {{ill|Jerzy Ochmański|pl}} | ||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 22,000–27,000 || 12,000 <!---- TOTAL: 39 ----> | |||

| | 18.000 | |||

| | 11.000 | |||

| | | |||

| | 16.000 + 3.000 ''guests'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ill|Sven Ekdahl|de}}{{sfn|Frost|2015|p=106}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 20,000–25,000 || 12,000–15,000 <!---- TOTAL: 40 ----> | |||

| | 12.000 heavy cavalry | |||

| | 7.200 light cavalry | |||

| | | |||

| | 11.000 heavy cavalry | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | | ] || 20,000 || 10,000 || 15,000 <!---- TOTAL: 45 ----> | ||

| | 20.000 | |||

| | 10.000 | |||

| | 1.000 | |||

| | 15.000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{ill|Jan Dąbrowski (historian)|lt=Jan Dąbrowski|pl|Jan Dąbrowski (historyk)}} || 15,000–18,000 || 8,000–11,000 || 19,000 <!---- TOTAL: 38 ----> | |||

| | ]<ref>p.43,Johnson</ref> | |||

| | 39.000 | |||

| | Lithuanians, Russians (Ruthenians), Tatars | |||

| | Czechs, Wallachians | |||

| | 27.000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ]{{sfn|Kiaupa|2002}} || 18,000 || 11,000 || 15,000–21,000 <!---- TOTAL: 40 ----> | |||

| | ]<ref name=Turnbul25/> | |||

| | 39.000 | |||

| | Lithuanians, Tatars, Ruthenians | |||

| | Czechs, Bohemians, Moravians | |||

| | 27.000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 19,000–20,000 || 10,000–11,000 || 21,000 <!---- TOTAL: 52 ----> | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 18.000 cavalry, 2.000 infantry, artillery | |||

| | 11.000 cavalry + 500 infantry Lithuanian , ca. 900 Ruthenians, ca. 300-1000 Tatars | |||

| | 300-600 Czechs, Moravians, Silesians, Moldavians | |||

| | 21.000 cavalry (3.700 mercenaries), 6.000 infantry, 5.000 serviceman, artillery. . | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ]{{sfn|Stone|2001|p=16}} || 27,000 || 11,000 || 21,000 <!---- TOTAL: 59 ----> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 39,000 || 27,000 <!---- TOTAL: 66 ----> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] and<br/> ]{{sfn|Thompson|Johnson|1937|p=940}} | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 100,000 || 35,000 <!---- TOTAL: 135 ----> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]{{sfn|Rambaud|1898}} | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 163,000 || 86,000 <!---- TOTAL: 249 ----> | |||

| |- | |||

| | '''Average''' | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align:center;"| 43,000 || 23,000 <!---- (TOTAL: 66) ----><!-- (for fun: R.M.S: 36,000 PL & 21,000 TK ) --> | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| <!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: ] from the 1960 Polish movie ], based on the 19th century ] of the same name, written by ] ]] --> | |||

| The precise number of soldiers involved has proven difficult to establish.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=25}} None of the contemporary sources provided reliable troop counts. ] provided the number of banners, the principal unit of each cavalry: 51 for the Teutons, 50 for the Poles and 40 for the Lithuanians.{{sfn|Ivinskis|1978|p=338}} However, it is unclear how many men were under each banner. The structure and number of infantry units (], ], ]men) and artillery units is unknown. Estimates, often biased by political and nationalistic considerations, were produced by various historians.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=25}} German historians tend to present lower numbers, while Polish historians tend to use higher estimates.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|pp=57–58}} The high-end estimates by Polish historian ] of 39,000 Polish–Lithuanian and 27,000 Teutonic men{{sfn|Ivinskis|1978|p=338}} have been cited in Western literature as "commonly accepted".{{sfn|Davies|2005|p=98}}{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=43}}{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=25}} | |||

| Regardless of such estimates, most of the modern historians count only the cavalry units. Apart from 16,000 cavalry, the Teutonic Order also fielded some 9,000 infantry, ] and ] troops and field artillery. Both armies also had large ]s, ] and other units, which made up some 10% of their total strength. | |||

| While outnumbered, the Teutonic army had advantages in discipline, military training and equipment.{{sfn|Разин|1999|p=486}} They were particularly noted for their heavy cavalry, although only a small percentage of the Order's army at Grunwald were heavily armoured knights.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=29}} The Teutonic army was also equipped with ] that could shoot lead and stone ].{{sfn|Разин|1999|p=486}} | |||

| Both armies were organised in '']s'', see ]. Each heavy cavalry banner was composed of approximately 240 mounted ]s as well as their squires and armour-bearers. Each banner flew its own standard and fought independently. Lithuanian banners were usually weaker and composed of approximately 180 light cavalry soldiers. The structure of foot units (], ], ]men) and the artillery is unknown. | |||

| Both armies were composed of troops from several states and lands, including numerous mercenaries, primarily from ] and ]. Bohemian mercenaries fought on both sides.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=29}} The Silesian mercenaries were led in battle by Duke ] the White, of ], who was supported by knights from the Silesian ] including ] and ].{{sfn|Ekdahl|2010b|p={{page needed|date=September 2021}}}} | |||

| The Teutonic Knights fielded fifty one banners.<ref name=Razin485>Razin, p. 485</ref> Razin citing the German estimates says that Order's army was 11 thousand strong, including about 4 thousand ], under 3 thousand ]s and about 4 thousand ] men.<ref name=Razin486>Razin, 486</ref> The Teutonian Army was also equipped with ]s that could shoot lead and stone ].<ref name=Razin486/> | |||

| Soldiers from twenty-two different states and regions, mostly Germanic, joined the Order's army.{{sfn|Разин|1999|pp=485–486}} Teutonic recruits known as guest crusaders included soldiers from ], ], ], ], ],{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=29}} and Stettin (]).{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=56}} Two Hungarian nobles, ] and ], brought 200 men for the Order,{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=139}} but support from ] was disappointing.{{sfn|Christiansen|1997|p=227}} | |||

| The more numerically strong allied force contained 16 to 17 thousand men including about three thousand ]s.<ref name=Razin486/> There were a total of 91 allied banners. Fifty Polish and 41 Lithuanian banners included Russian and Ruthenian lands controlled by Poland and Lithuania, respectively, as well as the banners from independent territories that joined the alliance (such as the Novgorod banner.) | |||

| Poland brought mercenaries from ] and Bohemia. The ] produced two full banners, under the command of ].{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=26}} Serving among the Czechs was possibly ], future commander of the ].{{sfn|Richter|2010}} ] commanded an expeditionary corps and the Moldavian king was so brave that the Polish troops and their king honoured him with a royal sword, the ].{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=138}} Vytautas gathered troops from ] and ]n lands (present-day Belarus and Ukraine). Among them were three banners from ] led by Władysław II Jagiełło's brother ], the Tatar contingent of the ] under the command of the future Khan ],{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=28}} and ] cavalry troops from ].{{sfn|Potashenko|2008|p=41}} The overall commander of the joint Polish–Lithuanian force was King Władysław II Jagiełło; however, he did not directly participate in the battle. The Lithuanian units were commanded directly by Grand Duke Vytautas, who was second in command, and helped design the ] of the campaign. Vytautas actively participated in the battle, managing both Lithuanian and Polish units.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=64}} ] stated that the low-ranking ] of the Crown, ], commanded the Polish army, but that is highly doubtful.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=63}} More likely, ] ] commanded the Polish troops in the field. | |||

| While less numerous, the Teutonic army had its own advantages, the discipline, the military training and superior military equipment.<ref name=Razin486/> | |||

| == Course of the battle == | |||

| Both sides included numerous mercenaries and were composed of troops coming from a variety of countries and lands. Twenty two different peoples, mostly Germanic, were represented at the Teutonic side.<Ref>Razin, pp. 485-486</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| === March into Prussia === | |||

| Apart from units fielded by lands of ], ] and the ], there were also mercenaries from Western Europe, ] that included ] and ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| The first stage of the Grunwald campaign was the gathering of all Polish–Lithuanian troops at ], a designated meeting point about {{convert|80|km|abbr=on}} from the Prussian border, where the joint army crossed the ] over a ].{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=33}} This maneuver, which required precision and intense coordination among multi-ethnic forces, was accomplished in about a week, from 24 to 30 June.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} Polish soldiers from ] gathered in ], and those from ], in ]. On 24 June, Władysław II Jagiełło and Czech mercenaries arrived in Wolbórz.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} Three days later the Polish army was already at the meeting place. The Lithuanian army marched out from ] on 3 June and joined the Ruthenian regiments in ].{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} They arrived in Czerwińsk on the same day the Poles crossed the river. After the crossing, Masovian troops under ] and ] joined the Polish–Lithuanian army.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=75}} The massive force began its march north towards Marienburg (]), capital of Prussia, on 3 July. The Prussian border was crossed on 9 July.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=33}} | |||

| The river crossing remained secret until Hungarian envoys, who were attempting to negotiate a peace, informed the Grand Master.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=141}} As soon as Ulrich von Jungingen grasped the Polish–Lithuanian intentions, he left 3,000 men at Schwetz (]) under ]{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=142}} and marched the main force to organize a line of defense on the Drewenz River (]) near Kauernik (]).{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=35}} The river crossing was fortified with ]s.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=76}} On 11 July, after meeting with his eight-member ],{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=63}} Władysław II Jagiełło decided against crossing the river at such a strong, defensible position. The army would instead bypass the river crossing by turning east, towards its sources, where no other major rivers separated his army from Marienburg.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=35}} The march continued east towards Soldau (]), although no attempt was made to capture the town.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=36}} The Teutonic army followed the Drewenz River north, crossed it near Löbau (]) and then moved east in parallel with the Polish–Lithuanian army. According to the Order's propaganda, the latter ravaged the village of Gilgenburg (]).{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|pp=36–37}} Later, in the self-serving testimonies of the survivors before the Pope, the order claimed that Von Jungingen was so enraged by the alleged atrocities that he swore to defeat the invaders in battle.{{sfn|Urban|2003|pp=148–149}} | |||

| The overall commander of the joint Polish-Lithuanian forces was king ], with the Polish units subordinated to Marshal of the Crown ] and Lithuanian units under the immediate command of Grand Duke of Lithuania ]. Until recently it was believed that the Sword Bearer of the Crown ] was the commander in chief of the joint army, but this idea was based on a false translation of the description of the battle by ]. The Teutonic Forces were commanded directly by the Grand Master of the Order ]. | |||

| == |

=== Battle preparations === | ||

| {{see also|Grunwald Swords}} | |||

| {| border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="0" style="font-size: 100%; border: gray solid 0px; border-collapse: collapse; text-align: center;" align="right" | |||

| ] as a gift to King ] (painting by ])]] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| The opposing forces formed their lines at dawn. At about noon the forces of Grand Duke of Lithuania ] started an all-out assault on the left flank of the Teutonic forces, near the village of Tannenberg (]). The Lithuanian cavalry was supported by a cavalry charge of several Polish banners on the right flank of the enemy forces. The enemy heavy cavalry counter-attacked on both flanks and fierce fighting occurred. | |||

| In the early morning of 15 July, both armies met in an area covering approximately {{convert|4|km2|abbr=on}} between the villages of ], Tannenberg (]) and Ludwigsdorf (]).{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=77}} The armies formed opposing lines along a northeast–southwest axis. The Polish–Lithuanian army was positioned in front and east of Ludwigsdorf and Tannenberg.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=44}} Polish heavy cavalry formed the left flank, Lithuanian light cavalry the right flank and various mercenary troops made up the center. Their men were organized in three lines of wedge-shaped formations about 20 men deep.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=44}} The Teutonic forces concentrated their elite heavy cavalry, commanded by Grand Marshal ], against the Lithuanians.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=77}} The order, which was the first to organize their army for the battle, hoped to provoke the Poles or Lithuanians into attacking first. Their troops, wearing heavy armor, had to stand in the scorching sun for several hours waiting for an attack.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=45}} One chronicle suggested that they had dug pits that an attacking army would fall into.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=149}} They also attempted to use ], but a light rain dampened their powder and only two cannon shots were fired.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=45}} As Władysław II Jagiełło delayed, the Grand Master sent messengers with two swords to "assist Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas in battle". The swords were meant as an insult and a provocation.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=43}} Known as the "]", they became one of the national symbols of Poland. | |||

| After more than an hour, the Lithuanian light cavalry started a retreat towards marshes and woods. This maneuver was often used in the east of Grand Duchy of Lithuania by Mongols. Vytautas, who had experience in battles against Mongols, used it in this battle. Only three banners of Smolensk commanded by Lengvenis (Simon Lingwen), son of Algirdas, brother of Jogaila and a cousin of Vytautas, remained on the right flank after the retreat of Vytautas and his troops. One of the banners was totally destroyed, while the remaining two were backed up by the Polish cavalry held in reserve and broke through the enemy lines to the Polish positions. | |||

| {{Clear|left}} | |||

| === Battle begins: Lithuanian attack and retreat maneuver === | |||

| Heavy cavalry of the Order started a disorganised pursuit after the retreating Lithuanians. The Knights entered the marshes, while Vytautas reorganized his forces to return to battle. | |||

| <gallery class="center" widths="250px" heights="150px"> | |||

| File:Battle of Grunwald map 2 English.jpg|Retreat of Lithuanian light cavalry (battle location and initial army positions according to an 1836 map by ] and contradicted by archaeological excavations in 2014–2017){{sfn|Ekdahl|2018|pp=243, 256, 257}} | |||

| File:Battle of Grunwald map 3 English.jpg|Right-flank Polish–Lithuanian assault | |||

| File:Battle of Grunwald map 4 English.jpg|Polish heavy-cavalry breakthrough | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| Vytautas, supported by the Polish banners, started an assault on the left flank of the Teutonic forces.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=45}} After more than an hour of heavy fighting, the Lithuanian light cavalry began a full retreat. ] described this development as a complete annihilation of the entire Lithuanian army. According to Długosz, the Order assumed that victory was theirs, broke their formation for a disorganized pursuit of the retreating Lithuanians, and gathered much loot before returning to the battlefield to face the Polish troops.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=78}} He made no mention of the Lithuanians, who later returned to the battlefield. Thus Długosz portrayed the battle as a single-handed Polish victory.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=78}} This view contradicted ''Cronica conflictus'' and has been challenged by modern historians. | |||

| Starting with an article by ] in 1909, they proposed that the retreat had been a planned maneuver borrowed from the ].{{sfn|Baranauskas|2011|p=25}} A ] had been used in the ] (1399), when the Lithuanian army had been dealt a crushing defeat and Vytautas himself had barely escaped alive.{{sfn|Sužiedėlis|1976|p=337}} This theory gained wider acceptance after the discovery and publication, in 1963 by Swedish historian {{ill|Sven Ekdahl|de}}, of a German letter.{{sfn|Urban|2003|pp=152–153}}{{sfn|Ekdahl|2010a}} Written a few years after the battle, it cautioned the new Grand Master to look out for feigned retreats of the kind that had been used in the Great Battle.{{sfn|Ekdahl|1963}} Stephen Turnbull asserts that the Lithuanian tactical retreat did not quite fit the formula of a feigned retreat; such a retreat was usually staged by one or two units (as opposed to almost an entire army) and was swiftly followed by a counterattack (whereas the Lithuanians had returned late in the battle).{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|pp=48–49}} | |||

| At the same time heavy fighting continued on the left flank of the Polish forces. After several hours of massed battle, the Teutonic cavalry started to gain the upper hand. According to ] the Grand Master ] personally led a cavalry charge on the strongest Polish unit — the Banner of the Land of ]. The Polish ranks started to waver and the flag of the banner was lost. However, it was soon recaptured by the Polish knights, and King Jogaila ordered most of his reserves to enter combat. The arrival of fresh troops allowed the Poles to repel the enemy assault and the forces of Ulrich von Jungingen were weakened. At the same time his reserves were busy pursuing the evading Lithuanian cavalry. | |||

| === Battle continues: Polish–Teutonic fight === | |||

| A pivotal role in triggering the Teutonic retreat is attributed to the leader of the banner of ](Culm),<ref>http://www.laborunion.lt/memorandum/ru/modules/banderia/primus.htm</ref><ref></ref> ] (Mikołaj of Ryńsk), born in Prussia (identified by Longinus as ]). The founder and leader of the ], a group of Order Knights sympathetic to Poland, refused to fight the Polish. Lowering the banner he was carrying was taken as a signal of surrender by the Teutonic troops. Accused of treason, ultimately von Renys was beheaded by his order, along with all of his male descendants. | |||

| ] fights a Teutonic knight (detail from a painting by ])]] | |||

| While the Lithuanians were retreating, heavy fighting broke out between Polish and Teutonic forces. Commanded by Grand Komtur {{ill|Kuno von Lichtenstein|de||pl||ru|Куно фон Лихтенштейн}}, the Teutonic forces concentrated on the Polish right flank. Six of von Walenrode's banners did not pursue the retreating Lithuanians, instead joining the attack on the right flank.{{sfn|Kiaupa|2002}} A particularly valuable target was the royal banner of ]. It seemed that the order were gaining the upper hand, and at one point the royal ], ], lost the Kraków banner.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=83}} However, it was soon recaptured and fighting continued. Władysław II Jagiełło deployed his reserves—the second line of his army.{{sfn|Kiaupa|2002}} Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen then personally led 16 banners, almost a third of the original Teutonic strength, to the right Polish flank,{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=53}} and Władysław II Jagiełło deployed his last reserves, the third line of his army.{{sfn|Kiaupa|2002}} The melee reached the Polish command and one knight, identified as Lupold or Diepold of Kökeritz, charged directly against King Władysław II Jagiełło.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=61}} Władysław's secretary, ], saved the king's life, gaining royal favor and becoming one of the most influential people in Poland.{{sfn|Stone|2001|p=16}} | |||

| === Battle ends: Teutonic Order defeated === | |||

| After several hours of fighting, Ulrich von Jungingen decided to join his embattled forces in the main line of engagement. At this time, however, ] returned to the battlefield with the reorganized forces of the ] and joined the fierce fighting. The Teutonic forces were by then becoming outnumbered by the mass of Polish knights and the advancing Lithuanians cavalry, which all of a sudden had come pouring on the battlefield from the surrounding forests. | |||

| ], '']'']] | |||

| At that time the reorganized Lithuanians returned to the battle, attacking von Jungingen from the rear.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=64}} The Teutonic forces were by then becoming outnumbered by the mass of Polish knights and advancing Lithuanian cavalry. As von Jungingen attempted to break through the Lithuanian lines, he was killed.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=64}} According to ''Cronica conflictus'', Dobiesław of Oleśnica thrust a lance through the Grand Master's neck,{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=64}} while Długosz presented ] as the killer. Surrounded and leaderless, the Teutonic Order began to retreat. Part of the routed units retreated towards their camp. This move backfired when the ]s turned against their masters and joined the manhunt.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=66}} The knights attempted to build a ]: the camp was surrounded by wagons serving as an improvised fortification.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=66}} However, the defense was soon broken and the camp was ravaged. According to ''Cronica conflictus'', more knights died there than on the battlefield.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=66}} The battle lasted for about ten hours.{{sfn|Kiaupa|2002}} | |||

| The Teutonic Order attributed the defeat to treason on the part of ] (Mikołaj of Ryńsk), commander of the Culm (]) banner, and he was beheaded without a trial.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=168}} He was the founder and leader of the ], a group of knights sympathetic to Poland. According to the order, von Renys lowered his banner, which was taken as a signal of surrender and led to the panicked retreat.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=79}} The legend that the order was "stabbed in the back" was echoed in the post-World War I ] and preoccupied ] of the battle until 1945.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=168}} | |||

| Ulrich von Jungingen personally led the assault with 16 banners of heavy cavalry, which until then were held in reserve. Jogaila, however, threw in all his remaining reserves, as well as several already tired units. Putting up heavy resistance, the 16 banners of the Grand Master were surrounded and began to suffer high losses, including the Grand Master himself. Seeing the fall of their Grand Master, the rest of the Teutonic forces started to withdraw towards their camp. | |||

| == Aftermath == | |||

| Part of the routed units retreated to the marshes and forests where they were pursued by the Lithuanian and Polish light cavalry, while the rest retreated to the camp near the village of ], where they tried to organise the defence by using the ] tactics: the camp was surrounded by wagons tied up with chains, serving as a mobile fortification. However, the defences were soon broken and the camp was looted. According to the anonymous author of the ''Chronicle of the Conflict of Ladislaus King of Poland with the Teutonic knights Anno Domini 1410'', there were more bodies in and around the camp than on the rest of the battlefield. The pursuit after the fleeing Teutonic cavalry lasted until the dusk. | |||

| === Casualties and captives === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| A note sent in August by envoys of ], ] and ], put total casualties at 8,000 dead "on both sides".{{sfn|Bumblauskas|2010|p=74}} However, the wording is vague and it is unclear whether it meant a total of 8,000 or 16,000 dead.{{sfn|Bumblauskas|2010|pp=74–75}} A papal bull from 1412 mentioned 18,000 dead Christians.{{sfn|Bumblauskas|2010|p=74}} In two letters written immediately after the battle, Władysław II Jagiełło mentioned that Polish casualties were small (''paucis valde'' and ''modico'') and Jan Długosz listed only 12 Polish knights who had been killed.{{sfn|Bumblauskas|2010|p=74}} A letter by a Teutonic official from Tapiau (]) mentioned that only half of the Lithuanians returned, but it is unclear how many of those casualties are attributable to the battle and how many to the later siege of Marienburg.{{sfn|Bumblauskas|2010|p=74}} | |||

| The defeat of the Teutonic Order was resounding. According to Teutonic payroll records, only 1,427 men reported back to Marienburg to claim their pay.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=68}} Of 1,200 men sent from Danzig, only 300 returned.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=56}} Between 203 and 211 brothers of the Order were killed, out of 270 that participated in battle,{{sfn|Frost|2015|pp=106–107}} including much of the Teutonic leadership—Grand Master ], Grand Marshal {{ill|Friedrich von Wallenrode|de||it||pl||eo}}, Grand Komtur {{ill|Kuno von Lichtenstein|de||pl||ru|Куно фон Лихтенштейн}}, Grand Treasurer Thomas von Merheim, Marshal of Supply Forces Albrecht von Schwartzburg, and ten of the ]s.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|pp=85–86}} ], Komtur of Brandenburg (]) and Heinrich Schaumburg, ] of ], were executed by order of Vytautas after the battle.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=68}} The bodies of von Jungingen and other high-ranking officials were transported to ] for burial on 19 July.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=87}} The bodies of lower-ranking Teutonic officials and 12 Polish knights were buried at the church in Tannenberg.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=87}} The rest of the dead were buried in several mass graves. The highest-ranking Teutonic official to escape the battle was Werner von Tettinger, Komtur of Elbing (]).{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=68}} | |||

| Despite the technological superiority of the Teutonic Knights, to the point of this being believed to be the first battle in this part of Europe in which field-artillery was deployed, the numbers and tactical superiority of the Polish Lithuanian alliance were to prove overwhelming. | |||

| Polish and Lithuanian forces took several thousand captives. Among these were Dukes ] of Oels (]) and ] of ].{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=69}} Most of the commoners and mercenaries were released shortly after the battle on condition that they report to ] on 11 November 1410.{{sfn|Jučas|2009|p=88}} Only those who were expected to pay ransom were kept. Considerable ransoms were recorded; for example, the mercenary Holbracht von Loym had to pay ''150 ] of ]'', amounting to more than {{convert|30|kg|0|abbr=on}} of silver.{{sfn|Pelech|1987|pp=105–107}} | |||

| The commander of the Czech forces ] lost his first eye in the battle, fighting on the side of the Polish-Lithuanian forces. | |||

| === Further campaign and peace === | |||

| == Aftermath == | |||

| {{main article|Siege of Marienburg (1410)|Peace of Thorn (1411)}} | |||

| ], detailing carnage after the Battle of Grunwald.]] | |||

| ], which served as the Teutonic capital, was ] for two months by the Polish–Lithuanian forces]] | |||

| The defeat of the ] was resounding. According to ] about 8,000 Teuton soldiers were killed in the battle, and an additional 14,000 taken captive. Most of the approximately 250 members of the Order were also killed, including much of the Teutonic leadership. Apart from ] himself, the Polish and Lithuanian forces killed also the Grand Marshal ], Grand Komtur ] and ], the Grand Treasurer ]. | |||

| After the battle, the Polish and Lithuanian forces delayed their attack on the Teutonic capital in Marienburg (]), remaining on the battlefield for three days and then marching an average of only about {{convert|15|km|abbr=on}} per day.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=162}} The main forces did not reach heavily fortified Marienburg until 26 July. This delay gave ] enough time to organize a defense. Władysław II Jagiełło also sent his troops to other Teutonic fortresses, which often surrendered without resistance,{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=164}} including the major cities of Danzig (]), Thorn (]), and Elbing (]).{{sfn|Stone|2001|p=17}} Only eight castles remained in Teutonic hands.{{sfn|Ivinskis|1978|p=342}} The besiegers of Marienburg expected a speedy capitulation and were not prepared for a long siege, suffering from lack of ammunition, low morale, and an epidemic of ].{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=75}} The order appealed to their allies for help, and ], ], and the ] promised financial aid and reinforcements.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=74}} | |||

| ], the Komtur of ], and mayor Schaumburg of ] were executed by order of Vytautas after the battle. The only higher officials to escape from the battle were Grand Hospital Master and Komtur of ] ]. Such a slaughter of noble knights and personalities was quite unusual in Mediæval Europe. This was possible mostly due to the participation of the peasantry who joined latter stages of the battle, and took part in destruction of the surrounded Teutonic troops. Unlike the noblemen, the peasants did not receive any ransom for taking captives; they thus had less of an incentive to keep them alive. Among those taken captive were ], duke of Stettin (]), and ], duke of Oels (]). | |||

| The siege of Marienburg was lifted on 19 September. The Polish–Lithuanian forces left garrisons in the fortresses they had taken and returned home. However, the order quickly recaptured most of the castles. By the end of October only four Teutonic castles along the border remained in Polish hands.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=166}} Władysław II Jagiełło raised a fresh army and dealt another defeat to the order in the ] on 10 October 1410. Following other brief engagements, both sides agreed to negotiate. | |||

| After the battle Polish and Lithuanian forces stayed on the battlefield for three days. All notable officials were interred in separate] graves, while the body of ] was covered with royal coat and transported to ]. The rest of the dead were gathered in several mass graves. There are different speculations as to why Jogaila decided to wait that long. After three days, the Polish-Lithuanian forces moved on to Marienburg and laid siege upon the castle, but the three days time had been enough for the knights to organise the defence. | |||

| Troops from ] were expected to support their brothers, and the ongoing conflict with ] could cause problems elsewhere. After several weeks of siege, the Lithuanian Grand Duke withdrew from the war and it became clear that the siege would not be effective. The nobility from Lesser Poland also wanted to end the war before the harvest, and the siege was lifted. | |||

| The ] was signed in February 1411. Under its terms, the order ceded the Dobrin Land (]) to Poland and agreed to resign their claims to ] during the lifetimes of Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas,{{sfn|Christiansen|1997|p=228}} although another two wars—the ] of 1414 and the ] of 1422—would be waged before the ] permanently resolved the territorial disputes.{{sfn|Kiaupa|Kiaupienė|Kuncevičius|2000|pp=142–144}} The Poles and Lithuanians were unable to translate the military victory into territorial or diplomatic gains. However, the Peace of Thorn imposed a heavy financial burden on the order from which they never recovered. They had to pay an indemnity in silver in four annual installments.{{sfn|Christiansen|1997|p=228}} To meet these payments, the order borrowed heavily, confiscated gold and silver from churches, and increased taxes. Two major Prussian cities, Danzig (]) and Thorn (]), revolted against the tax increases.{{sfn|Turnbull|2003|p=78}} The defeat at Grunwald left the Teutonic Order with few forces to defend their remaining territories. Since Samogitia became officially ], as both Poland and Lithuania were for a long time, the order had difficulties recruiting new volunteer crusaders.{{sfn|Christiansen|1997|pp=228–230}} The Grand Masters then needed to rely on mercenary troops, which proved an expensive drain on their already depleted budget. The internal conflicts, economic decline, and tax increases led to unrest and the foundation of the ], or ''Alliance against Lordship'', in 1441. This in turn led to a series of conflicts that culminated in the ] (1454).{{sfn|Stone|2001|pp=17–19}} | |||

| In the battle, both Polish and Lithuanian forces had taken several thousand captives. Most of the mercenaries were released shortly after the battle on the condition that they will return to ] on 29 September 1410. After that move, the king held most of the Teutonic officials, while the rest returned to Prussia to beg the Teutonic Order officials for their liberation and ransom payment. This proved to be a major drain of the Teutonic budget as the value of a Teutonic Knight was quite high. | |||

| == Battlefield memorials == | |||

| For instance, one of the mercenaries named ] had to pay ''sixty times'' ({{lang-de|]}}) ''the number of 150 ]'', that is over 30 ]s of pure silver, which is worth roughly 10000 USD or EUR in modern times, but before the discovery of South America and its silver and gold, could be estimated at the times of the crusades <ref>http://www.mittelalter-server.de/Mittelalter-Geld/Das-Mittelalter-Geld-im-Mittelalter_Preise.html</ref> at about a million $ or €. With his army defeated and the remnants of it composed mostly of ill-paid mercenaries, ] had little incentive to continue the fight, especially since some of the Hanseatic cities owned by the knights had changed sides. Thus, after retaking ] from rebellious burghers, the peace negotiations were started. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Ideas about commemorating the battle rose right after the event. Władysław II Jagiełło wanted to build a monastery dedicated to Saint ], who had prophesied the downfall of the Teutonic Order, at the location of the battle.{{sfn|Petrauskas|2010|p=224}} When the order regained the territory of the battlefield, the new grand master ] built a chapel dedicated to Saint Mary and it was consecrated in March 1413.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2019|p=45}} It was destroyed by the Poles when they invaded during the ] of 1414, but it was quickly rebuilt. The chapel fell to ruins during the ] and was demolished in 1720.{{sfn|Knoll|1983|p=72}}{{sfn|Odoj|2014|p=64}} Over time, the location of the chapel became associated with the location where Grand Master ] was killed. In 1901, a large memorial stone was erected for the fallen Grand Master in the midst of the chapel ruins for the 200th anniversary of the coronation of King ]. The inscription was chiseled in 1960 and the stone was removed from the chapel ruins and placed inscription facing down in 1984.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2019|pp=45–46}} | |||

| In 1960, for the 550th anniversary, a museum and monuments were constructed a little northeast of the chapel ruins.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=186}} The grounds were designed by sculptor ] and architect {{ill|Witold Cęckiewicz|pl}}. The monuments included an obelisk of ]n granite depicting two faces of knights, a bundle of eleven {{convert|30|m|adj=on}}-high flagpoles with emblems of the Polish–Lithuanian army, and a sculptural map depicting the supposed positions of the armies before the battle.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=186}} Presumed locations where Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautas had their main camps were marked with artificial mounds and flagpoles.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=186}} The battle site is one of Poland's national ], as designated on 4 October 2010, and tracked by the ]. The museum, which is open during summers, has an exhibition space of {{convert|275|m2}} in which it displays archaeological finds from the battlefield, original and reproduced medieval weapons, reconstructed flags from the battle, as well as various maps, drawings, and documents related to the battle.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://muzeumgrunwald.fbrothers.com |title=Historia Muzeum Bitwy pod Grunwaldem w Stębarku |publisher=Muzeum Bitwy pod Grunwaldem w Stębarku |language=pl |access-date=17 September 2021 }}</ref> In 2018, the museum was visited by about 140,000 people.<ref>{{cite web |first=Zygmunt|last=Kruczek |url=https://zarabiajnaturystyce.pl/fileadmin/user_upload/Frekwencja_w_atrakcjach_turystycznych_w_latach_2016-2018.pdf |page=69 |publisher=Polska Organizacja Turystyczna |title=Frekwencja w atrakcjach turystycznych w latach 2016–2018 |year=2019 |language=pl}}</ref> Construction of a larger year-round museum at an estimated cost of 30 million ] (6.5 million euros) started in April 2019.<ref>{{cite web |first=Agnieszka |last=Libudzka |url=https://dzieje.pl/aktualnosci/wmurowano-kamien-wegielny-pod-budowe-calorocznego-muzeum-bitwy-pod-grunwaldem |title=Wmurowano kamień węgielny pod budowę całorocznego Muzeum Bitwy pod Grunwaldem |publisher=Dzieje.pl |language=pl |access-date=17 September 2021 }}</ref> | |||

| According to the ] signed in February 1411, the Order had to cede the ] (Dobrzyń Land) to Poland, and resign their claims to ] for the lifetime of the king. This is thought to be a diplomatic defeat for Poland and Lithuania as they pushed for attempts to dismantle the ] state altogether. However, while the Poles and Lithuanians were unable to translate the military victory in the battle to greater geographical gains, the financial consequences of the peace treaty were much worse for the knights, having to pay about 5 tons of silver in each of the next four years. | |||

| In July 2020, a large stone with engraved ] was erected by the Lithuanians near the monument site to commemorate the 610th anniversary of the battle. The monument was unveiled by Lithuanian and Polish presidents ] and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1183423/memorial-stone-to-mark-lithuanian-polish-victory-against-teutonic-crusaders|title=Memorial stone to mark Lithuanian-Polish victory against Teutonic crusaders |website=LRT |date=29 May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| The defeat of Teutonic knights' troops left them with few forces to defend their remaining territories. The Grand Masters from then on had to rely on mercenary troops, which proved too expensive for the knights' budget to sustain. Although ], the successor to ], managed to keep hold on territories conquered by knights, the opposition to his rule among the citizens, the knights and within the Order itself forced his ouster. | |||

| == Archaeological excavations == | |||

| The Teuton knights' lost support due to their internal conflicts and constant tax increases, which decades later was manifested in the foundation of the ], or ''Alliance against Lordship'', in 1441. This led to a series of conflicts that culminated in 1454 the ], ending with another defeat of the humiliated order. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | width = 250 | |||

| | image1 = Traditional Army Movements at the Battle of Grunwald.png | caption1=Traditional view of army movements and battlefield location according to descriptions by ] and map first published by ] in 1836{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018}} | |||

| | image2 = Modern Army Movements at the Battle of Grunwald.png | caption2=Proposed army movements and battlefield locations according to Sven Ekdahl{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018}} | |||

| }} | |||

| Several artifacts from the battlefield are known from historical record, for example stone balls in the church of ] (Tannenberg) and a metal helmet with holes in the church of ] which was gifted to ] when he visited the battlefield in 1842, but they have not survived to the present day.{{sfn|Odoj|2014|p=58}}<ref name=drej>{{cite web |url=http://www.jandlugosz.edu.pl/artykuly/s-drej-z-dziejow-badan-archeologinczych-pol-grunwaldzkich |first=Szymon |last=Drej |title=Z dziejów badań archeologicznych pól grunwaldzkich |work=jandlugosz.edu.pl |publisher=Polish Historical Society and the Historical Magazine "Mówią wieki" |year=2015 |language=pl |access-date=18 September 2021}}</ref> The first amateur archeological research was carried out in 1911 in hopes of finding the mass graves mentioned by Jan Długosz at the church of Stębark.<ref name=drej/> The church was surveyed with ] in 2013 but little evidence of the mass graves was found.{{sfn|Tanajewski|Odoj|Oszczak|Godlewska|2014}} | |||

| The first more thorough archaeological ] were carried out in 1958–1960 in the run-up to the 550th anniversary, connected to the construction of the memorial site and museum. The government showed great interest in the excavations and sent helicopters and 160 soldiers to help.<ref name=drej/> Research continued in later decades, but yielded very little results with the exception of the area around the ruined chapel.{{sfn|Odoj|2014|p=62}}{{sfn|Knoll|1983|p=72}} Several mass graves were found at the chapel: remains of six people in the vestibule, 30 people next to the southern wall, more than 130 people in three pits adjacent to the chapel, and about 90 people in the ]. Many remains showed signs of traumatic injuries. Some skeletons showed signs of being burned and moved.<ref name=drej/> Mass burials, including of women and children, were also found in the villages of Gilgenburg (]) and Faulen (]). The massacre in Gilgenburg was known from written sources, but the burial in Faulen was unexpected.<ref name=drej/> In the fields, very few items of ] were found. In 1958–1990, only 28 artefacts were found connected to the battle: ten crossbow bolts, five arrowheads, a javelin head, two sword pieces, two gun bullets, six pieces of gauntlets, and two small arms bullets.<ref name=drej/> | |||

| The next year the Polish and Lithuanian leaders celebrated the victory with a sort of a re-enactment parade, and a voyage to visit their neighbours, Polotsk, Smolensk and Riazan, but seemingly their visits failed to impress, maybe because the monarchs made the journey without their armies, but in ships down the Dniepr to Kiev.<ref>p.278, Mickunaite</ref> | |||

| In 2009 Swedish historian {{ill|Sven Ekdahl|de}} published his long-held hypothesis that the traditionally accepted location of the battlefield was incorrect. He believed that the surveys near the chapel ruins were actually around the site of the Teutonic Order's camp. According to Ekdahl's theory, the main battlefield was located northeast of the road between Grunwald and Łodwigowo, about {{convert|2|km}} southwest of the memorial site.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018|pp=241, 246}} Between 2014 and 2019, archaeologists from Scandinavia and Poland investigated an area of approximately {{convert|450|ha}} with metal detectors and located the main battle site according to Ekdahl's predictions.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018|p=265}} In 2017, the team found approximately 65 crossbow bolts and 20 arrowheads, as well as parts of spurs, stirrups, gauntlets, etc.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2018|p=258}} As of 2020, archaeologists had discovered about 1,500 artifacts of which about 150 are linked to the battle. Among them are a Teutonic clasp to fasten coat with the Gothic inscription 'Ave Maria', a seal with the image of a pelican feeding its young with blood, two well preserved axes, and Teutonic coins.<ref>{{cite web| url=https://scienceinpoland.pap.pl/en/news/news%2C83697%2Ctwo-axes-battle-1410-found-near-grunwald.html |first=Marcin |last=Boguszewski |title=Two axes from the Battle of 1410 found near Grunwald |publisher=PAP – Science in Poland |date= 2 September 2020 |access-date=18 September 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ==Influences of the Battle of Grunwald on modern culture== | |||

| ===Poland=== | |||

| ] in a 2003 reconstruction of the battle.]] | |||

| The 2014-2019 surveys have been criticsed due to inconsistent publications and not following scientific techniques established by battlefield archeology. These include preservation of findings, lack of survey maps and inconsistent recording of GPS data. There has also been a lack of funding from the Polish government for reliable research of the entire battlefield.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Strzyż |first1=Piotr |last2=Wrzosek |first2=Jakub |title=(Review) Sven Ekdahl, In Search of the Battlefield of Tannenberg (Grunwald) of 1410. New Research with Metal Detectors in 2014–2019, Vilnius 2019, pp. 279. : On the Problems of Battlefield Research |journal=Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae |date=13 December 2021 |volume=34 |pages=159–162 |doi=10.23858/FAH34.2021.012 |url=https://journals.iaepan.pl/fah/article/view/2936 |access-date=8 April 2024 |language=en |issn=2719-7069|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| The battle of Grunwald is regarded as one of the most important battles in Polish history.<ref>p.44,Johnson</ref> It is often depicted by an ] of two swords, which were supposedly given to the King ] and the Grand Duke Vytautas before the battle by the Teutonic knights envoys to "raise Polish desire for battle". | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| ], with its double swords.]] | |||

| ] of the ] during commemoration of the battle of Žalgiris in ] on 15 July 1930.]] | |||

| In ]'s summary, almost all accounts of the battle made before the 1960s were more influenced by romantic legends and nationalistic propaganda than by fact.{{sfn|Urban|2003|p=168}} Historians have since made progress towards dispassionate scholarship and reconciliation of the various national accounts of the battle.{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=44}} | |||

| In 1914, on the eve of World War I, during celebration of the five-hundredth anniversary of the battle, a monument by ] was erected in ]. The ceremony spawned demonstrations of outrage within Polish society against the aggressive politics of the ], including the forcible ] of ] after the ]. Polish poet ] wrote the fiercely patriotic, poem, ] calling to defence against Germanisation policies. About the same time, ] wrote the novel '']'' (Polish: ''Krzyżacy''), one of his series of books designed to increase patriotic spirit amongst the Poles (forty-four years later, Polish filmmaker ] used the book as the basis for his film, '']''). | |||

| Today, a festival is held every year to commemorate this medieval battle. Thousands of ] from all across Europe, many of them in knight's armour, gather in July at the Grunwald fields to reconstruct the battle. Great care is taken with the historical details of the armour, weapons, and conduct of the battle. | |||

| ] was erected in ], Poland for the battle's 500th anniversary. It was destroyed during World War II by the Germans and rebuilt in 1976.]] | |||

| The Soviets used the symbols of the battle for propaganda purposes and created the ] (''The Cross of Grunwald'' medal) which was a ] created in 1943 by the commander of the Soviet proxy force ] (confirmed in 1944 by the ]) and awarded for heroism in World War II. | |||

| === Poland and Lithuania === | |||

| Some Polish ]s, including ], are named in memory of the Polish victory. | |||

| The Battle of Grunwald is regarded as one of the most important in the histories of Poland and Lithuania.{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=43}} In Lithuania, the victory is synonymous with the Grand Duchy's political and military peak. It was a source of national pride during the age of ] and inspired resistance to the ] and ] policies of the ] and ]s. The Teutonic Order was portrayed as bloodthirsty invaders and Grunwald as a just victory achieved by a small, oppressed nation.{{sfn|Johnson|1996|p=43}} | |||

| In 1910, to mark the 500th anniversary of the battle, ] by ] was unveiled in ] during a three-day celebration attended by some 150,000 people.{{sfn|Dabrowski|2004|pp=164–165}} About 60 other towns and villages in ] also erected Grunwald monuments for the anniversary.{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=179}} About the same time, ]-winner ] wrote the novel '']'' (Polish: ''Krzyżacy''), prominently featuring the battle in one of the chapters. In 1960, Polish filmmaker ] used the book as the basis for his film, '']''. At the ], Poland exhibited the ] which commemorated the battle and was later installed in the ], ].{{sfn|Ekdahl|2008|p=183}} The battle has lent its name to military decorations (]), sports teams (], ]), and various organizations. 72 streets in Lithuania are named after the battle.<ref>{{cite web|first=Nemira |last=Pumprickaitė |title=VU rektorius apie Žalgirio mūšį ir istorinį lūžį: regione atsirado nauja valdžia ir galybė – Lietuva ir Lenkija |url=https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/lietuvoje/2/1197898/vu-rektorius-apie-zalgirio-musi-ir-istorini-luzi-regione-atsirado-nauja-valdzia-ir-galybe-lietuva-ir-lenkija |publisher=] |date=15 July 2020 |language=lt}}</ref> | |||

| ===Belarus=== | |||

| In the 15th century present-day ] was part of the ]. Many cities from the region contributed troops to the Grand Duchy's side. The victory in the Battle of Grunwald is widely respected and commemorated. | |||

| ] (left) during the annual recreation of the battle in 2003]] | |||

| ===Lithuania=== | |||

| <!-- no separate rationale for this article ]--> | |||

| ] | |||

| The victory at the Battle of Grunwald or ''Žalgirio mūšis'' in 1410 is synonymous with the peak of the political and military power of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The demise of the Teutonic order ended the period of German expansion and created preconditions for political stability, economic growth and relative cultural prosperity that lasted until the rise of ] in the late 16th century. In the Lithuanian historical discourse regarding the battle there is a lasting controversy over the roles played by the Lithuanian-born king of Poland ], and his cousin, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, ], the latter usually being favoured as a national hero. There is also well known speculation about two swords which were presented to ] before battle; why two swords for one commander? Some historians believe that Teutonic Order sent one sword for ], but as he was commanding on the field of battle both of them were presented to ]. This episode reflects a wider controversy: to what extent was Vytautas subordinate to his cousin Jogaila, if at all? | |||

| Under Communist rule over Poland, memory to the battle was monopolized by the state. Memory to the battle was instrumentalized for justifying the new borders, under which Poland annexed ], while losing the ]. Under the ], anti-German ] was reduced, but the symbol of Grunwald did not disappear. Until end of the 1980s, July 15 was an important official memorial day.<ref name ="Erinnerungsorte">chapter=Schlacht bei Tannenberg/ Erfolg und Scheitern von Siegesmythen|series=Deutsch-Polnische Erinnerungsorte: Geteilt/Gemeinsam| volume=Geteilt/Gemeinsam|publisher=Ferdinand Schöningh|year= 2012|editors=Robert Traba, Peter Oliver Loew, Maciej Górny, Kornelia Kończal|publisher=Ferdinand Schöningh|pages=296-297}}</ref> | |||

| The term ''Žalgiris'' became a symbol of resistance to foreign domination over Lithuania. The leading Lithuanian ] and ] teams are called ] and ] to commemorate the battle. The victories of BC Žalgiris Kaunas against the Soviet Army sports club ] in the late 1980s served as a major emotional inspiration for the Lithuanian national revival, and the consequent emergence of the ] movement that helped lead to the collapse of the Soviet Union. The historical reason for such inspirations may seem obscure. Contemporary chronicler Jan Dlugosz in ''Historiae Poloniae (Lib. X)'' describes the Lithuanians as "showing their back and running all along towards Lithuania" from the battlefield. This however could simply be propaganda at a time in which the Polish nobles came to dominate more and more the twin state of Poland-Lithuania. In fact it was the leadership of the two Lithuanian born Noblemen, Jogaila and Vytautas, who proved to be decisive for the allied victory. The so called fleeing of the Lithuanian light cavalry might have been a tactical move which at a later stage of the battle proved to be decisive when those troops regrouped and attended the battlefield again, striking the final blow to the tired forces of the order. | |||

| An annual ] takes place on 15 July. In 2010, a pageant reenacting the event and commemorating the battle's 600th anniversary was held. It attracted 200,000 spectators who watched 2,200 participants playing the role of knights in a re-enactment of the battle. An additional 3,800 participants played peasants and camp followers. The pageant's organisers believe that the event has become the largest re-enactment of medieval combat in Europe.{{sfn|Fowler|2010}} The reenactment attracts about 60,000 to 80,000 visitors annually.{{sfn|Kruczek|2015|p=52}} | |||

| ===Germany=== | |||

| In Germany the battle was known as the Battle of Tannenberg. In 1914 yet another ] took place between Germany and Russia, ending with a Russian defeat. In German propaganda during the World War I / World War II period the 1914 battle was put forth as a revenge for the Polish - Lithuanian victory 504 years earlier, and the battle itself was purposefully named to suit this agenda. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Russia and the Soviet Union=== | |||