| Revision as of 04:37, 25 March 2009 edit98.23.199.75 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:04, 19 January 2025 edit undoBeach drifter (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers8,065 edits Reverted 1 edit by 2001:569:BED3:5D00:F953:FDD:5B6B:7601 (talk): RvvTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|City in the United States}} | |||

| {{redirect|Albuquerque}} | {{redirect|Albuquerque}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox Settlement | |||

| {{infobox settlement | |||

| |name = City of Albuquerque | |||

| | name = Albuquerque | |||

| |nickname = <!--Note: Please do not add nickname or motto without discussing on talk page first.--> | |||

| | settlement_type = ] | |||

| |motto = <!--Note: Please do not add nickname or motto without discussing on talk page first.--> | |||

| |image_skyline |

| image_skyline = {{Multiple image | ||

| | |

|align = center | ||

| | |

|border = infobox | ||

| | |

|perrow = 1/2/2/1/1 | ||

| |total_width = 300 | |||

| |image_seal = Albuquerque New Mexico logo.png | |||

| |caption_align = center | |||

| |image_map = Bernalillo_County_New_Mexico_Incorporated_and_Unincorporated_areas_Albuquerque_Highlighted.svg | |||

| | |

|image1 = Abqdowntown.jpg | ||

| | |

|caption1 = ] | ||

| | |

|image2 = Sandia Peak Tramway Car by Anna Cummings Photography.jpg | ||

| | |

|caption2 = ] | ||

| | |

|image3 = Albuquerque Alvarado Transportation Building.JPG | ||

| | |

|caption3 = ] | ||

| |image4 = San Felipe de Neri Church-Albuquerque.jpg| | |||

| |subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | |

|caption4 = ] | ||

| | |

|image5 = Rio Grande-2.jpg | ||

| | |

|caption5 = ] | ||

| |image6 = AIBF Mass Ascent, 2007.jpg | |||

| |subdivision_name2 = ] | |||

| | |

|caption6 = ] | ||

| |leader_title = ] | |||

| |leader_name = ] <small>''' 3rd term'''</small> | |||

| |leader_title1 = City Council | |||

| |leader_name1 = {{Collapsible list | |||

| |title = Councilors | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| |1 = (Dist #1) Ken Sanchez (]) | |||

| |2 = (Dist #2) Debbie O'Malley (]) | |||

| |3 = (Dist #3) Isaac Benton (]) | |||

| |4 = (Dist #4) Bradley "Brad" Winter (]) | |||

| |5 = (Dist #5) Michael J. Cadigan (]) | |||

| |6 = (Dist #6) Rey Garduño (]) | |||

| |7 = (Dist #7) Sally Mayer (]) | |||

| |8 = (Dist #8) Trudy Jones (]) | |||

| |9 = (Dist #9) Don Harris (]) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | image_flag = Flag of Albuquerque, New Mexico.svg | |||

| |leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | |

| seal_size = 80px | ||

| | flag_size = 120px | |||

| |title = Representatives | |||

| | flag_link = Flag of Albuquerque, New Mexico | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| | image_seal = Seal of Albuquerque, New Mexico.svg | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| | nicknames = The Duke City, ABQ, The 505, Burque, The Q. | |||

| |1 = Henry "Kiki" Saavedra (]) | |||

| | motto = <!--Note: Please do not add nicknames or motto without discussing on talk page first.--> | |||

| |2 = Rick Miera (]) | |||

| | image_map = {{maplink | |||

| |3 = Ernest H. Chavez (]) | |||

| |frame = yes | |||

| |4 = Eleanor Chavez (]) | |||

| |plain = yes | |||

| |5 = Miguel P. Garcia (]) | |||

| |frame-align = center | |||

| |6 = Teresa Zanetti (]) | |||

| |frame-width = 290 | |||

| |7 = Antonio "Moe" Maestas (]) | |||

| |frame-height = 290 | |||

| |8 = Edward C. Sandoval (]) | |||

| |frame-coord = {{coord|35.0850|-106.6500}} | |||

| |9 = Gail Chasey (]) | |||

| |zoom = 10 | |||

| |10 = Sheryl M. Williams-Stapleton (]) | |||

| |type = shape | |||

| |11 = Richard J. Berry (]) | |||

| |marker = city | |||

| |12 = Mimi Stewart (]) | |||

| |stroke-width = 2 | |||

| |13 = Kathy McCoy (]) | |||

| |stroke-color = #0096FF | |||

| |14 = Eric A. Youngberg (]) | |||

| |fill = #0096FF | |||

| |15 = Janice Arnold-Jones (]) | |||

| |id2 = Q34804 | |||

| |16 = Danice R. Picraux (]) | |||

| |type2 = shape-inverse | |||

| |17 = Al Park (]) | |||

| |stroke-width2 = 2 | |||

| |18 = Lorenzo "Larry" Larranaga (]) | |||

| |stroke-color2 = #5F5F5F | |||

| |19 = Jimmie C. Hall (]) | |||

| |stroke-opacity2 = 0 | |||

| |20 = ] (]) | |||

| |fill2 = #000000 | |||

| |21 = William Rehm (]) | |||

| |fill-opacity2 = 0 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | map_caption = Interactive map of Albuquerque | |||

| |leader_title3 = ] | |||

| | |

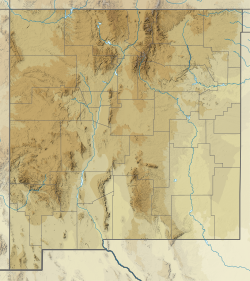

| pushpin_map = New Mexico#USA | ||

| | pushpin_map_caption = Location in New Mexico##Location in the United States | |||

| |title = State senators | |||

| | pushpin_relief = 1 | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| | coordinates = {{Wikidatacoord|Q34804|region:US-NM_type:city|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| |1 = John Ryan (]) | |||

| | subdivision_name = United States | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = State | |||

| |3 = ] (]) | |||

| | subdivision_type2 = ] | |||

| |4 = ] (]) | |||

| | subdivision_type3 = ] | |||

| |5 = Eric Griego (]) | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| |6 = H. Diane Snyder (]) | |||

| | subdivision_name2 = ] | |||

| |7 = ] (]) | |||

| | subdivision_name3 = ] | |||

| |8 = Mark Boitano (]) | |||

| | established_title = Founded | |||

| |9 = Sue Wilson Beffort (]) | |||

| | established_date = 1706 (as Alburquerque) | |||

| |10 = William H. Payne (]) | |||

| | established_title2 = ] | |||

| |11 = Kent L. Cravens (]) | |||

| | established_date2 = 1891 (as Albuquerque) | |||

| |12 = Linda Lovejoy (]) | |||

| | founder = ] | |||

| |13 = Joseph J. Carraro (]) | |||

| | named_for = ] | |||

| |14 = ] (]) | |||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] (]) | |||

| | leader_title1 = ] | |||

| | leader_name1 = {{Collapsible list | |||

| |title = Councilors | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| |1 = '''5 ],<br />4 ]''' | |||

| |2 = Louie Sánchez (]) | |||

| |3 = Tammy Fiebelkorn (]) | |||

| |4 = Isaac Benton (]) | |||

| |5 = Dan Lewis (]) | |||

| |6 = Brooke Bassan (]) | |||

| |7 = Pat Davis (]) | |||

| |8 = Klarissa J. Peña (]) | |||

| |9 = Trudy Jones (]) | |||

| |10 = Renee Grout (]) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | unit_pref = Imperial | |||

| |leader_title4 = ] | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 489.39 | |||

| |leader_name4 = {{Collapsible list | |||

| | area_total_sq_mi = 194.93 | |||

| |title = Representative | |||

| | area_land_km2 = 486.03 | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| | area_land_sq_mi = 188.27 | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| | area_water_km2 = 4.35 | |||

| |1 = ] (]) | |||

| | area_water_sq_mi = 1.62 | |||

| | area_footnotes = <ref name="TigerWebMapServer">{{cite web |title=ArcGIS REST Services Directory |url=https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer/5/query?where=STATE%3D%2735%27&outFields=NAME%2CSTATE%2CPLACE%2CAREALAND%2CAREAWATER%2CLSADC%2CCENTLAT%2CCENTLON&orderByFields=PLACE&returnGeometry=false&returnTrueCurves=false&f=json |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=October 12, 2022 |archive-date=May 31, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230531092538/https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer/5/query?where=STATE%3D%2735%27&outFields=NAME%2CSTATE%2CPLACE%2CAREALAND%2CAREAWATER%2CLSADC%2CCENTLAT%2CCENTLON&orderByFields=PLACE&returnGeometry=false&returnTrueCurves=false&f=json |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | elevation_footnotes = <ref name=gnis/> | |||

| | elevation_ft = 5312 | |||

| | population_total = 564559 | |||

| | population_as_of = ] | |||

| | population_footnotes = <ref name="USCensusDecennial2020CenPopScriptOnly"/> | |||

| | population_rank = ] in North America<br />] in the United States<br />] in New Mexico | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 3014.68 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 1163.97 | |||

| | population_urban = 769,837 (]) | |||

| | population_density_urban_km2 = 1,129.9 | |||

| | population_density_urban_sq_mi = 2,926.3 | |||

| | population_metro_footnotes = <ref name="2020Pop">{{cite web |title=2020 Population and Housing State Data |url=https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=August 23, 2021 |archive-date=August 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824081449/https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | population_metro = 960000 (]) | |||

| | population_demonym = Albuquerquean (uncommon), Burqueño, Burqueña | |||

| | pop_est_footnotes = | |||

| | pop_est_as_of = | |||

| | population_est = | |||

| | postal_code_type = ]s | |||

| | postal_code = 87101–87125, 87131,<br />87151, 87153, 87154,<br />87158, 87174, 87176,<br />87181, 87184, 87185,<br />87187, 87190–87199 | |||

| | area_codes = ] | |||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | leader_name2 = {{collapsible list | |||

| |title = Representatives | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| |1 = '''13 ],<br />11 ]''' | |||

| |2 = G. Andres Romero (]) | |||

| |3 = Javier Martínez (]) | |||

| |4 = Patricio Ruiloba (]) | |||

| |5 = Eleanor Chavez (]) | |||

| |6 = Patricia Roybal Caballero (]) | |||

| |7 = Miguel Garcia (]) | |||

| |8 = Sarah Maestas Barnes (]) | |||

| |9 = Antonio Maestas (]) | |||

| |10 = Deborah Armstrong (]) | |||

| |11 = Gail Chasey (]) | |||

| |12 = Sheryl M. Williams-Stapleton (]) | |||

| |13 = Jim Dines (]) | |||

| |14 = Stephanie Maez (]) | |||

| |15 = James Smith (]) | |||

| |16 = Paul Pacheco (]) | |||

| |17 = Conrad James (]) | |||

| |18 = Christine Trujillo (]) | |||

| |19 = Georgene Louis (]) | |||

| |20 = Larry Larranaga (]) | |||

| |21 = Jimmie C. Hall (]) | |||

| |22 = David Adkins (]) | |||

| |23 = Nathaniel Gentry (]) | |||

| |24 = William Rehm (]) | |||

| |25 = Monica Youngblood (]) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | leader_title3 = ] | |||

| |established_title = Founded | |||

| | leader_name3 = {{Collapsible list | |||

| |established_date = 1706 ''as: Albu'''''r'''''querque'' | |||

| |title = State senators | |||

| |established_title2 = ] | |||

| |frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; | |||

| |established_date2 = 1891 ''as: Albuquerque'' | |||

| |list_style = text-align:left;display:none; | |||

| |area_magnitude = 1 E9 | |||

| |1 = '''1 ],<br />13 ]''' | |||

| |area_total_km2 = 469.5 | |||

| |2 = ] (]) | |||

| |area_total_sq_mi = 181.3 | |||

| |3 = ] (]) | |||

| |area_land_km2 = 467.9 | |||

| |4 = ] (]) | |||

| |area_land_sq_mi = 180.6 | |||

| |5 = ] (]) | |||

| |area_water_km2 = 1.7 | |||

| |6 = ] (]) | |||

| |area_water_sq_mi = 0.6 | |||

| |7 = ] (]) | |||

| |population_density_km2 = 1079.9 | |||

| |8 = ] (]) | |||

| |population_density_sq_mi = 2796.0 | |||

| |9 = ] (]) | |||

| |population_as_of = 2007 | |||

| |10 = ] (]) | |||

| |population_footnotes = | |||

| |11 = ] (]) | |||

| <ref name="Census PopEst over 100,000 2007" /> | |||

| |12 = ] (]) | |||

| <ref name="Census PopEst MSA 2007" /> | |||

| | |

|13 = ] (]) | ||

| | |

|14 = ] (]) | ||

| }} | |||

| |population_blank1_title = ] | |||

| | leader_title4 = ] | |||

| |population_blank1 = Albuquerquean | |||

| | leader_name4 = ] (D)<br />] (D) | |||

| |population_blank2_title = ]<ref name=raceinformation>. City Data</ref> | |||

| | timezone = ] | |||

| |population_blank2 = <br>49.9% ] <br /> 39.9% ]<br /> 4.9% ] <br /> 4.3% ] <br /> 3.1% ] <br /> 0.6% ]<br /> 14.8% Others | |||

| | utc_offset = −7 | |||

| |timezone = ] | |||

| | timezone_DST = ] | |||

| |utc_offset = -7 | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = −6 | |||

| |timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| |utc_offset_DST = -6 | |||

| | |

| blank_info = 35-02000 | ||

| | blank1_name = ] feature ID | |||

| |postal_code = 87101, 87102, 87103, 87104,<br> 87105, 87106, 87107, 87108,<br> 87109, 87110, 87111, 87112,<br> 87113, 87114, 87115, 87116,<br> 87117, 87118, 87119, 87120,<br> 87121, 87122, 87123, 87124,<br> 87125, 87131, 87144, 87151,<br> 87153, 87154, 87158, 87174,<br> 87176, 87181, 87184, 87185,<br> 87187, 87190, 87191, 87192,<br> 87193, 87194, 87195, 87196,<br> 87197, 87198, 87199 | |||

| | blank1_info = 2409678<ref name=gnis>{{GNIS|2409678 }}</ref> | |||

| |area_code = 505 | |||

| | website = {{official URL}} | |||

| |latd = 35 |latm = 06 |lats = 39 |latNS = N | |||

| |longd = 106 |longm = 36 |longs = 36 |longEW = W | |||

| |elevation_m = 1619.1 | |||

| |elevation_ft = 5312 | |||

| |website = http://www.cabq.gov/ | |||

| |blank_name = ] | |||

| |blank_info = 35-02000 | |||

| |blank1_name = ] feature ID | |||

| |blank1_info = 0928679 | |||

| ---- | |||

| |blank2_name = Primary Airport | |||

| |blank2_info = ]- <br>ABQ (Major/International) | |||

| |blank3_name = Secondary Airport | |||

| |blank3_info = ]-<br> KAEG (Public) | |||

| |footnotes = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Albuquerque''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|æ|l|b|ə|k|ɜɹ|k|i|audio=en-us-Albuquerque.ogg}} {{respell|AL|bə|kur|kee}}; {{IPA|es|alβuˈkeɾke|lang|Pronunciation of Albuquerque in Spanish.ogg}}),{{efn|Spanish also {{lang|es|Alburquerque}} {{IPA|es|alβuɾˈkeɾke||Alburquerque.ogg}}; {{langx|nv|Beeʼeldííl Dahsinil}} {{IPA|nv|peː˩ʔe˩ltiː˥l ta˩hsi˩ni˩l|}}; {{langx|kee|Arawageeki}}; {{langx|tow|Vakêêke}}; {{langx|zun|Alo:ke:k'ya}}; {{langx|apj|Gołgéeki'yé}}.}} also known as '''ABQ''', '''Burque''', the '''Duke City''', and in the past ''''the Q'''', is the ] in the U.S. state of ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/albuquerquecitynewmexico/PST045217 |title=U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Albuquerque city, New Mexico |website=Census Bureau QuickFacts |access-date=September 15, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180915121930/https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/albuquerquecitynewmexico/PST045217 |archive-date=September 15, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> Founded in 1706 as ''{{lang|es|La Villa de Alburquerque}}'' by ] governor ], and named in honor of ] and ], it was an ] on ] linking Mexico City to the northernmost territories of ]. | |||

| Located in the ], the city is flanked by the ] to the east and the ] to the west, with the ] and ] flowing north-to-south through the middle of the city.<ref name="Isolated Traveller 2021">{{cite web |date=October 6, 2021 |title=30 Interesting Facts About Albuquerque |url=https://www.isolatedtraveller.com/20-interesting-facts-about-albuquerque/ |access-date=May 17, 2022 |website=Isolated Traveller |archive-date=May 16, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220516054336/https://www.isolatedtraveller.com/20-interesting-facts-about-albuquerque/ |url-status=live }}</ref> According to the ], Albuquerque had 564,559 residents,<ref name="QuickFacts">{{cite web |title=QuickFacts: Albuquerque city, New Mexico |url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/albuquerquecitynewmexico/POP010220 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=August 24, 2021 |archive-date=June 10, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240610123140/https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/albuquerquecitynewmexico/POP010220 |url-status=live }}</ref> making it the ] in the United States and the fourth largest in the ]. The ] had 955,000 residents in 2023, and forms part of the ], which had a population of 1,162,523.<ref name="TIGERweb Redirect 2020">{{cite web |title=Combined Statistical Areas - 2020 Census - Data as of January 1, 2020 |website=TIGERweb Redirect |date=January 1, 2020 |url=https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/tigerwebmain/Files/bas22/tigerweb_bas22_csa_2020_tab20_us.html |access-date=May 17, 2022 |archive-date=June 27, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220627155455/https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/tigerwebmain/Files/bas22/tigerweb_bas22_csa_2020_tab20_us.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| '''Albuquerque''' ({{pronEng|ˈælbəkɝki}}, ] {{IPA2|alβuˈkeɾke}}; known as ''Bee'eldííldahsinil'' in ]) is the largest ] in the ] of ], ]. It is the ] of ] and is situated in the central part of the state, straddling the ]. The city population was 518,271 as of July 1, 2007 ] estimates <ref name="Census PopEst over 100,000 2007"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |url= http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/tables/SUB-EST2007-01.csv | |||

| |title= Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places Over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2007 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007 (SUB-EST2007-01) | |||

| |accessdate= 2008-07-15 | |||

| |date= 2008-07-10 | |||

| |publisher= US Census Bureau, Population Division | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> and ranks as the ] city in the U.S. As of June 2007, the city was the 6th fastest growing in America.<ref name=autogenerated1></ref> With a metropolitan population of 845,913 as of July 1, 2008,<ref name="Census PopEst MSA 2007"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |url= http://www.census.gov/popest/metro/tables/2008/CBSA-EST2008-01.xls | |||

| |title= Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 | |||

| |accessdate= 2008-07-15 | |||

| |date= 2008-03-27 | |||

| |publisher= US Census Bureau, Population Division | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Albuquerque is the ] ]. The ] population includes the city of ], one of the fastest growing cities in the United States<!-- Citation Needed -->. | |||

| Albuquerque is a hub for technology, fine arts, and ].<ref name="Shankland 2021">{{cite web |last=Shankland |first=Stephen |title=Intel investing $3.5B in New Mexico fab upgrade, boosting US chipmaking |website=CNET |date=May 3, 2021 |url=https://www.cnet.com/tech/mobile/intel-investing-3-5b-in-new-mexico-fab-upgrade-boosting-us-chipmaking/ |access-date=May 17, 2022 }}</ref><ref name="ABQ Film Office 2010">{{cite web |title=Making Movies in the 505 |website=ABQ Film Office |date=January 1, 2010 |url=https://www.abqfilmoffice.com/ |access-date=May 17, 2022 }}</ref> It is home to several ],<ref name="City of Albuquerque Historic Landmarks">{{cite web |title=Historic Landmarks |website=City of Albuquerque |date=March 14, 2022 |url=https://www.cabq.gov/planning/boards-commissions/landmarks-commission/historic-landmarks |access-date=May 17, 2022 |archive-date=May 24, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220524100953/https://www.cabq.gov/planning/boards-commissions/landmarks-commission/historic-landmarks |url-status=live }}</ref> the ], the ], the ], the ], and a diverse ], which features both ] and ].<ref name="Food Com 2018">{{cite web |title=An Albuquerque Appetite: Where to Eat in New Mexico's Biggest City |website=Food Com |date=May 24, 2018 |url=https://www.foodnetwork.com/restaurants/photos/restaurant-guide-albuquerque |access-date=May 17, 2022 |archive-date=May 17, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220517160110/https://www.foodnetwork.com/restaurants/photos/restaurant-guide-albuquerque |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Albuquerque is home to the ] (UNM), ] and the ] and ]. The ] run along the eastern side of Albuquerque, and the ] flows through the city, north to south. | |||

| {{toclimit|3}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| === Early settlers === | |||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: ] --> | |||

| The city was founded in 1706 as the ] colonial outpost of ''Ranchos de Alburquerque''; present-day Albuquerque retains much of the Spanish cultural and historical heritage. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Albuquerque was a farming community and strategically located military outpost along the ]. The town of Alburquerque was built in the traditional Spanish village pattern: a central plaza surrounded by government buildings, homes, and a church. This central plaza area has been preserved and is open to the public as a museum, cultural area, and center of commerce. It is referred to as "Old Town Albuquerque" or simply "Old Town." "Old Town" was sometimes referred to as "La Placita" ("little plaza" in Spanish). | |||

| {{Main|History of Albuquerque, New Mexico}} | |||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| ] carved into basalt in the western part of the city bear testimony to a Native American presence in the area dating back many centuries.<ref>{{Cite web |date=March 20, 2021 |title=What are Petroglyphs |url=https://www.nps.gov/petr/learn/historyculture/what.htm |access-date=June 19, 2024 |website=National Park Service |archive-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240619160738/https://www.nps.gov/petr/learn/historyculture/what.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> These are preserved in the ]. | |||

| The village was named by the provincial governor Don Francisco Cuervo y Valdes in honour of Don ], viceroy of ] from 1653 to 1660. One of de la Cueva's aristocratic titles was Duke of Alburquerque, referring to ]. The first "r" in "Alburquerque" was dropped at some point in the 19th century, supposedly by an ] railroad station-master unable to pronounce the city's name correctly. Some New Mexicans still prefer the spelling ''Alburquerque''; see for example the book by that name by ]. In the 1990s, the Central Avenue Trolley Buses were emblazoned with the name ''Alburquerque'' (with two "r"s) in honor of the city's historic name. {{Fact|date=August 2008}} | |||

| The ] and ] peoples had lived along the Rio Grande for centuries before European colonists arrived in the area that developed as Albuquerque. By the 1500s, there were around 20 ] pueblos along a {{convert|60|mi|km|adj=on}} stretch of river from present-day ] to the ] confluence south of ]. Of these, 12 or 13 were densely clustered near present-day ], and the remainder were spread out to the south.<ref name=barrett>{{cite book |last1=Barrett |first1=Elinore M. |title=Conquest and Catastrophe: Changing Rio Grande Pueblo Settlement Patterns in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries |date=2002 |publisher=UNM Press |location=Albuquerque |isbn=9780826324139 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rLAICgAAQBAJ |access-date=September 25, 2017 |language=en |via=Google Books }}</ref> | |||

| The Alburquerque family name dates from pre-12th century Iberia (Spain and Portugal) and is habitational in nature (de Alburquerque = from Alburquerque). The Spanish village of ] is within the ] province of Spain, and located just fifteen miles (24 km) from the Portuguese border. Cork trees dominate the landscape and Alburquerque is a center of the Spanish cork industry.<ref>James J. Parsons. The Cork Oak Forests and the Evolution of the Cork Industry in Southern Spain and Portugal. 1962. Clark University</ref> Over the years, this region has been alternately under both Spanish and Portuguese rule. (It is interesting to note that the Portuguese spelling has only one 'r'). Historically, the land around Alburquerque was invaded and settled by the Moors (711 AD) and the Romans (218 BC) before them. Thus, the word Alburquerque may be rooted in the Arabic (Moorish) 'Abu al-Qurq', which means "father of the cork oak", or "land of the cork oak" (the land as father - fatherland). Alternately, it may be Latin (Roman) in origin and from 'albus quercus' or "white oak" (the wood of the cork oak is white after the bark has been removed). The seal of the Spanish village of Alburquerque is a white oak tree, framed by a shield, topped by a crown.<ref>Brochure "Alburquerque: Villa Medieval" Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Alburquerque and Banco Bilbao Vizcaya. 2006</ref> | |||

| Two Tiwa ] lie on the outskirts of present-day Albuquerque. Both have been continuously inhabited for many centuries: ] was founded in the 14th century,<ref>{{cite web |title=History of Sandia Pueblo |work=Sandia Pueblo website |publisher=Pueblo of Sandia |year=2006 |url=http://www.sandiapueblo.nsn.us/history.html |access-date=January 17, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080102031937/http://www.sandiapueblo.nsn.us/history.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archive-date=January 2, 2008 }}</ref> and ] is documented in written records since the early 17th century. It was then chosen as the site of the ], a ]. | |||

| <!-- Need to have something about the 1800s to 1850s, the war against Mexico to occupy these territories. --> | |||

| During the ] Albuquerque was occupied in February 1862 by ] troops under General ], who soon afterwards advanced with his main body into northern New Mexico. During his retreat from ] troops into ] he made a stand on April 8, 1862 at Albuquerque. A day-long engagement at long range led to few casualties against a detachment of Union soldiers commanded by Colonel ]. | |||

| The historic ], ], and ] peoples were likely to have set camps in the Albuquerque area, as there is evidence of trade and cultural exchange among the different Native American groups going back centuries before European arrival.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Seymour |first1=Deni |title=From the Land of Ever Winter to the American Southwest |date=2012 |publisher=University of Utah Press }}</ref> | |||

| When the ] arrived in 1880, it bypassed the Plaza, locating the passenger depot and railyards about <span style="white-space:nowrap">2 miles (3 km)</span> east in what quickly became known as New Albuquerque or New Town. To quell its then rising violent crime rate, ] ] was appointed the town's first ] that same year. New Albuquerque was incorporated as a town in 1885, with ] its first mayor, and incorporated as a city in 1891.<ref name="Simmons">{{cite book | last = Simmons | first = Marc | title = Albuquerque | publisher = University of New Mexico Press | location = Albuquerque | year = 1982 | isbn = 0826306276 }}</ref>{{Rp|232–233}} Old Town remained a separate community until the 1920s when it was absorbed by the City of Albuquerque. ], the city's first public high school, was established in 1879. | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| Albuquerque was founded in 1706 as an outpost as ''La Villa de Alburquerque'' by ] in the provincial kingdom of ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=About – Albuquerque Historical Society |url=http://albuqhistsoc.org/who-we-are/ |website=Albuquerque Historical Society |access-date=January 4, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151219010115/http://albuqhistsoc.org/who-we-are/ |archive-date=December 19, 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> The settlement was named after the original town of Viceroy ], 10th ], who was from ] in southwest Spain. | |||

| Albuquerque developed primarily for farming and sheep herds. It was a strategically located trading and military outpost along the ]. It served other ] and ] towns settled in the area, such as ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nmallstar.com/albuquerque_visitor_information.html |title=History |publisher=Nmallstar.com |access-date=February 18, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120325201851/http://www.nmallstar.com/albuquerque_visitor_information.html#Albuquerques |archive-date=March 25, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| === Early 20th Century === | |||

| ] | |||

| New Albuquerque quickly became a tidy southwestern town which by 1900 boasted a population of 8,000 inhabitants and all the modern amenities including an electric street railway connecting Old Town, New Town, and the recently established ] campus on the East Mesa. In 1902 the famous Alvarado Hotel was built adjacent to the new passenger depot and remained a symbol of the city until it was torn down in 1970 to make room for a parking lot. In 2002, the ] was built on the site in a manner resembling the old landmark. The large metro station functions as the downtown headquarters for the city's transit department, and serves as an intermodal hub for local buses, ] buses, ] passenger trains, and the ] commuter rail line. | |||

| After gaining independence in 1821, Mexico established a military presence here. The town of Alburquerque was built in the traditional Spanish villa pattern: a central ] surrounded by government buildings, homes, and a church. This central plaza area has been preserved and is open to the public as a cultural area and center of commerce. It is referred to as "]" or simply "Old Town". Historically it was sometimes referred to as "La Placita" (''Little Plaza'' in Spanish). On the north side of Old Town Plaza is ]. Built in 1793, it is one of the oldest surviving buildings in the city.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.stoppingpoints.com/nm/Bernalillo/San+Felipe+de+Neri+Church.html |author=New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, Historic Preservation Division |title=San Felipe de Neri Church Historical Marker |access-date=December 5, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130513010127/http://www.stoppingpoints.com/nm/Bernalillo/San+Felipe+de+Neri+Church.html |archive-date=May 13, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| New Mexico's dry climate brought many ] patients to the city in search of a cure during the early 1900s, and several sanitaria sprang up on the ] to serve them. Presbyterian Hospital and St. Joseph Hospital, two of the largest hospitals in the Southwest, had their beginnings during this period. Influential ]-era governor ] and famed southwestern architect ] were among those brought to New Mexico by tuberculosis. | |||

| After the New Mexico Territory became a part of the United States in the mid-19th century, a federal garrison and quartermaster depot, the Post of Albuquerque, were established here, operating from 1846 to 1867. In ''Beyond the Mississippi'' (1867), ], traveling to California via coach, passed through Albuquerque in late October 1859—its population was 3,000 at the time—and described it as "one of the richest and pleasantest towns, with a Spanish cathedral and other buildings more than two hundred years old."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Richardson |first=Albert D. |title=Beyond the Mississippi: From the Great River to the Great Ocean |publisher=American Publishing Co. |year=1867 |location=Hartford, Conn. |pages=249 }}</ref> | |||

| === Decades of growth === | |||

| During the ], Albuquerque was occupied for a month in February 1862 by ] troops under General ]. He soon afterward advanced with his main body into northern New Mexico.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} During his retreat from ] troops into ], he made a stand on April 8, 1862, and fought the ] against a detachment of Union soldiers commanded by Colonel ]. This daylong engagement at long range led to few casualties. The residents of Albuquerque aided the Republican Union to rid the city of the occupying Confederate troops.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| On June 2007 Albuquerque was listed as the 6th fastest growing city in America by CNN and the US Census Bureau.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The first travelers on ] appeared in Albuquerque in 1926, and before long, dozens of motels, restaurants, and gift shops had sprung up along the roadside to serve them. Route 66 originally ran through the city on a north-south alignment along Fourth Street, but in 1937 it was realigned along ], a more direct east-west route. The intersection of Fourth and Central downtown was the principal crossroads of the city for decades. The majority of the surviving structures from the Route 66 era are on Central, though there are also some on Fourth. Signs between ] and ] along the old route now have brown, historical highway markers denoting it as ''Pre-1937 Route 66.'' | |||

| When the ] arrived in 1880, it bypassed the Plaza, locating the passenger depot and railyards about <span style="white-space:nowrap">2 miles (3 km)</span> east in what quickly became known as New Albuquerque or New Town. The railway company built a hospital for its workers that was later used as a juvenile psychiatric facility. It has since been converted to a hotel.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Galloway |first1=Lindsey |title=A hospital turned hotel in New Mexico |url=http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20130520-a-hospital-turned-hotel-in-new-mexico |publisher=BBC Travel |access-date=July 15, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170511180757/http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20130520-a-hospital-turned-hotel-in-new-mexico |archive-date=May 11, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The establishment of ] in 1939, Sandia Base in the early 1940s, and ] in 1949, would make Albuquerque a key player of the Atomic Age. Meanwhile, the city continued to expand outward onto the West Mesa, reaching a population of 201,189 by 1960. In 1990 it was 384,736 and in 2007 it was 518,271. | |||

| Many Anglo merchants, mountain men, and settlers slowly filtered into Albuquerque, creating a major mercantile commercial center in ]. From this commercial center on July 4, 1882, ] became the first to fly a balloon in Albuquerque with a landing at Old Town.<ref name="Fogel">{{Cite book |last=Fogel |first=Gary |title=Sky Rider: Park Van Tassel and the Rise of Ballooning in the West |publisher=University of New Mexico Press |location=Albuquerque |year=2021 |isbn=978-0-8263-6282-7 }}</ref> This was the first balloon flight in the New Mexico Territory. | |||

| Albuquerque's downtown entered the same phase and development (decline, "urban renewal" with continued decline, and gentrification) as nearly every city across the United States. As Albuquerque spread outward, the downtown area fell into a decline. Many historic buildings were razed in the 1960s and 1970s to make way for new plazas, high-rises, and parking lots as part of the city's urban renewal phase. Only recently has downtown come to regain much of its urban character, mainly through the construction of many new loft apartment buildings and the renovation of historic structures like the ], in the ] phase. | |||

| Due to a rising rate of violent crime, gunman ] was appointed the town's first marshal that year. New Albuquerque was incorporated as a town in 1885, with Henry N. Jaffa its first mayor. It was incorporated as a city in 1891.<ref name="Simmons">{{Cite book |last=Simmons |first=Marc |title=Albuquerque |publisher=University of New Mexico Press |location=Albuquerque |year=1982 |isbn=0-8263-0627-6 }}</ref>{{Rp|232–233}} | |||

| === New millennium === | |||

| During the 21st century, the Albuquerque population has continued to grow rapidly. The population of the city proper is estimated at 518,271 in 2007, up from 448,607 in the 2000 census.<ref name="Census PopEst over 100,000 2007" /> The metropolitan area population is estimated at 835,120 in 2007, up from 729,649 in the 2000 census. <ref name="Census PopEst MSA 2007" /> | |||

| Old Town remained a separate community until the 1920s, when it was absorbed by Albuquerque. ], the city's first public high school, was established in 1879. ], a ] synagogue established in 1897, by Henry N. Jaffa, who was also the city's first mayor, is the oldest continuing Jewish organization in the city.<ref name="congregationalbert.org">{{cite web |title=Our History |website=Congregation Albert |date=April 7, 1902 |url=https://www.congregationalbert.org/history |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240526083553/https://www.congregationalbert.org/history |archive-date=May 26, 2024 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| During 2005 and 2006, the city celebrated its tricentennial with a diverse program of cultural events. | |||

| ], built in 1914. Victorian and Gothic styles were used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.|alt=|left]] | |||

| By 1900, Albuquerque boasted a population of 8,000 and all the modern amenities, including an electric street railway connecting Old Town, New Town, and the recently established University of New Mexico campus on the East Mesa.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} In 1902, the ] was built adjacent to the new passenger depot, and it remained a famous symbol of the city for decades.<ref>{{Cite news |date=1969 |title=The Alvarado Hotel |url=https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1658&context=nma |work=New Mexico Architect |pages=20–23 |via=University of New Mexico |archive-date=August 20, 2024 |access-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240820041409/https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1658&context=nma |url-status=live }}</ref> Outdated, it was razed in 1970 and the site was converted to a parking lot.<ref>{{Cite news |date=1970 |title=The Alvarado Hotel |url=https://wheelsmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Alvarado-Hotel.pdf |access-date=June 19, 2024 |work=New Mexico Architect |pages=16–19 |via=Wheels Museum }}</ref> | |||

| === Urban trends and issues === | |||

| Government leaders and many citizens in the city have actively pursued urban projects taken on by cities many times larger{{Fact|date=August 2008}}. This has resulted in the somewhat successful revitalization of downtown, creating restaurants, offices, and residential lofts. The strip of Central Avenue between First and Eighth streets has become a hub of urban life. Alvarado provides convenient access to other parts of the city via ] the city bus system. The city wants to provide better public transportation opportunities to ease the city's growing traffic woes. A street car is being considered and would initially extend up the Central Avenue corridor from the westside, through downtown, past UNM and the Nob Hill district, and into the Uptown Area.<ref></ref> | |||

| In 2002, the ] was built on the site in a style resembling the old landmark. The large metro station functions as the downtown headquarters for the city's transit department. It also is an intermodal hub for local buses, ] buses, ] passenger trains, and the ] commuter rail line.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| Many citizens fear Albuquerque may be growing beyond its means. A majority of residents want to avoid increasing crime and traffic, worsening air quality, stressing water supplies, and encroaching on the natural environment. Many feel these are the negative consequences of persistent sprawl development patterns.{{Fact|date=June 2008}} | |||

| In the early days of transcontinental air service, Albuquerque was an important stop on many transcontinental air routes, earning it the nickname "Crossroads of the Southwest".<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://kirtland.baseguide.net/history.html |title=Kirtland AFB Guide/Directory - History |website=kirtland.baseguide.net |access-date=July 2, 2023 |archive-date=July 2, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702014927/http://kirtland.baseguide.net/history.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| On March 23, 2007, the city's mayor ] announced his plan to brand the city "]". Despite various opinions as to what the city's nickname should be, Mayor Chavez is continuing to push his initiative. | |||

| During the early 20th century, New Mexico's dry climate attracted many ] patients to the city in search of a cure;<ref>{{Cite web |title=Department of Health reports progress against tuberculosis in New Mexico |url=https://www.nmhealth.org/news/awareness/2021/3/?view=1420 |access-date=December 10, 2024 |website=www.nmhealth.org |archive-date=July 23, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240723045005/https://www.nmhealth.org/news/awareness/2021/3/?view=1420 |url-status=live }}</ref> this was before penicillin was found to be effective. Several sanitaria were developed on the ] for TB patients. Presbyterian Hospital and St. Joseph Hospital, two of the largest hospitals in the Southwest, had their beginnings during this period. Influential ]–era governor ] and famed Southwestern architect ] were among those who came to New Mexico seeking recovery from TB.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| ], "I am from Burque", is one response to the mayor's vision of a "hip" reincarnation".<ref></ref> This group of Albuquerque’s residents feels it is unnecessary to spend taxpayer money to hire marketing companies to brand their city with a more palatable nickname, recognizing the city already has a brand and nickname. This selling of a city’s ] to marketing and advertising firms to brand and sell has been dubbed by ] as culture branding. One central issue to their response is the branding campaign was never voted on, but rather declared by Mayor Chavez,<ref></ref> and ]d to marketing and advertising firms. | |||

| The passage of the Planned Growth Strategy in 2002-2004 marked the community's strongest effort to create a framework for a more balanced and sustainable approach to urban growth.<ref></ref> | |||

| ], built in 1915, is one of downtown Albuquerque's many historic buildings|alt=|left]] | |||

| "A critical finding of the study is that many of the 'disconnects' between the public's preferences and what actually is taking place are caused by weak or non-existent implementation tools - rather than by inadequate policies, as contained in the City/County Comprehensive Plan and other already adopted legislation." | |||

| The first travelers on ] appeared in Albuquerque in 1926. Soon dozens of motels, restaurants, and gift shops sprouted along the roadside. Route 66 originally ran through the city on a north–south alignment along Fourth Street. In 1937 it was realigned along ], a more direct east–west route.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} The intersection of Fourth and Central downtown was the principal crossroads of the city for decades. The majority of the surviving structures from the Route 66 era are on Central, though there are also some on Fourth. Signs between Bernalillo and Los Lunas along the old route now have brown, historical highway markers denoting it as ''Pre-1937 Route 66.''{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| Urban sprawl is limited on three sides by the ] of Sandia to the north, the Pueblo of Isleta and ] to the south, and the ] to the east. Suburban growth continues at a strong pace to the west beyond the Petroglyph National Monument, once thought to be a natural boundary to sprawl development.<ref></ref> | |||

| The establishment of ] in 1939, ] in the early 1940s, and ] in 1949, would make Albuquerque a key player of the Atomic Age. Meanwhile, the city continued to expand outward into the Northeast Heights, reaching a population of 201,189 by 1960 per the U.S. Census.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/population-and-housing-phc-1/41953654v1ch2.pdf |title=U.S. Census of Population and Housing: 1960. Census Tracts. |date=1961 |publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |series=Final Report PHC(1)-4. |location=Washington, D.C. |pages=13 |archive-date=June 19, 2024 |access-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240619163207/https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/population-and-housing-phc-1/41953654v1ch2.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Because of cheaper land and lower taxes, much of the growth in the metropolitan area is taking place outside of the City of Albuquerque itself. In Rio Rancho to the northwest, the communities east of the mountains, and the incorporated parts of ], population growth rates approach twice that of the city. The primary cities in Valencia County are ] and ], both of which are home to growing industrial complexes and new residential subdivisions. The ] (MRCOG), which includes constituents from throughout the Albuquerque area, was formed to insure that these governments along the middle Rio Grande would be able to meet the needs of their rapidly rising populations. MRCOG's cornerstone project is the ]. | |||

| By 1990, it was 384,736 and in 2007 it was 518,271. In June 2007, Albuquerque was listed as the sixth fastest-growing city in the United States.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{Cite news |author=Les Christie |url=https://money.cnn.com/2007/06/27/real_estate/fastest_growing_cities/ |title=The fastest growing U.S. cities – June 28, 2007 |publisher=CNN |date=June 28, 2007 |access-date=May 9, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130404170946/http://money.cnn.com/2007/06/27/real_estate/fastest_growing_cities/ |archive-date=April 4, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1990, the ] reported Albuquerque's population as 34.5% Hispanic and 58.3% non-Hispanic white.<ref name="census1">{{cite web |title=Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990 |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |url=https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html |access-date=April 23, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080912052919/http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html |archive-date=September 12, 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| On April 11, 1950, a USAF ] carrying a ] crashed into a mountain near ].<ref>{{cite web |author=Tiwari J, Gray CJ |title=U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accidents |url=http://www.cdi.org/Issues/NukeAccidents/accidents.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120423145613/http://www.cdi.org/issues/nukeaccidents/accidents.htm |archive-date=April 23, 2012 }}</ref> On May 22, 1957, a B-36 accidentally dropped a ] 4.5 miles from the control tower while landing at ]. Only the conventional trigger detonated, as the bomb was unarmed. These incidents were not reported as they were classified as secret for decades.<ref>Adler, Les. {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190515060717/http://www.hkhinc.com/newmexico/albuquerque/doomsday/ |date=May 15, 2019 }} ''Albuquerque Tribune''. January 20, 1994.</ref> | |||

| Following the end of ], population shifts as well as suburban development, ] and gentrification, Albuquerque's downtown entered a period of decline. Many historic buildings were razed in the 1960s and 1970s to make way for new plazas, high-rises, and parking lots as part of the city's urban renewal phase.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} {{as of|2010}}, only recently has Downtown Albuquerque come to regain much of its urban character,{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} mainly through the construction of many new loft apartment buildings and the renovation of historic structures such as the ]. | |||

| During the 21st century, Albuquerque's population has continued to grow rapidly. The population of the city proper was estimated at 564,559 in 2020,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Explore Census Data |url=https://data.census.gov/profile/Albuquerque_city,_New_Mexico?g=160XX00US3502000 |access-date=November 7, 2024 |website=data.census.gov |archive-date=November 8, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20241108214453/https://data.census.gov/profile/Albuquerque_city,_New_Mexico?g=160XX00US3502000 |url-status=live }}</ref> 528,497 in 2009, and 448,607 in the 2000 census.<ref>{{Cite news |first=Erick |last=Siermers |title=Managing Albuquerque's growth |url=http://www.abqtrib.com/news/2007/sep/17/albuquerque-metro-area-population-projected-reach-/ |date=September 17, 2007 |access-date=September 17, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100222005227/http://abqtrib.com/news/2007/sep/17/albuquerque-metro-area-population-projected-reach-/ |archive-date=February 22, 2010 }}</ref> During 2005 and 2006, the city celebrated its tricentennial with a diverse program of cultural events. | |||

| The passage of the Planned Growth Strategy in 2002–2004 was the community's strongest effort to create a framework for a more balanced and sustainable approach to urban growth.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cabq.gov/council/pgs.html |title=Planned Growth Strategy |publisher=Cabq.gov |date=March 19, 2007 |access-date=July 2, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080517213447/http://www.cabq.gov/council/pgs.html |archive-date=May 17, 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| Urban sprawl is limited on three sides—by the ] to the north, the ] and Kirtland Air Force Base to the south, and the Sandia Mountains to the east. Suburban growth continues at a strong pace to the west, beyond the Petroglyph National Monument, once thought to be a natural boundary to sprawl development.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/petr/ |title=Petroglyph National Monument |publisher=Nps.gov |date=June 10, 2010 |access-date=July 2, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100828110802/http://www.nps.gov/petr/ |archive-date=August 28, 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Because of less-costly land and lower taxes, much of the growth in the metropolitan area is taking place outside of the city of Albuquerque itself. In Rio Rancho to the northwest, the communities east of the mountains, and the incorporated parts of ], population growth rates approach twice that of Albuquerque. The primary cities in Valencia County are ] and ], both of which are home to growing industrial complexes and new residential subdivisions. The mountain towns of ], ], and ], while close enough to Albuquerque to be considered suburbs, have experienced much less growth compared to Rio Rancho, Bernalillo, Los Lunas, and Belen. Limited water supply and rugged terrain are the main limiting factors for development in these towns. The ] (MRCOG), which includes constituents from throughout the Albuquerque area, was formed to ensure that these governments along the middle Rio Grande would be able to meet the needs of their rapidly rising populations. MRCOG's cornerstone project is currently the ].{{Citation needed|date=May 2024}} | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| According to the ], Albuquerque has a total area of <span style="white-space:nowrap">181.3 square miles (469.6 km²)</span>. <span style="white-space:nowrap">180.6 square miles (467.8 km²)</span> of it is land and <span style="white-space:nowrap">0.6 square miles (1.6 km²)</span> of it (0.35%) is water. The metro area has over {{convert|1000|sqmi|km2}} developed.{{Fact|date=January 2009}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Albuquerque lies within the northern, upper edges of the ] ecoregion, based on long-term patterns of climate, associations of plants and wildlife, and landforms, including drainage patterns. Located in central New Mexico, the city also has noticeable influences from the adjacent ] Semi-Desert, Arizona-New Mexico Mountains, and Southwest Plateaus and Plains Steppe ecoregions, depending on where one is located. Its main geographic connection lies with southern New Mexico, while culturally, Albuquerque is a crossroads of most of New Mexico. | |||

| ] | |||

| Albuquerque is located in north-central New Mexico. To its east are the ]. The ] flows north to south through its center, while the ] and ] make up the western part of the city. Albuquerque has one of the highest elevations of any major city in the U.S., ranging from {{convert|4,900|ft|m}} ] near the ] to over {{convert|6,700|ft|m}} in the foothill areas of ] and Glenwood Hills. The civic apex is found in an undeveloped area within the Albuquerque Open Space; there, the terrain rises to an elevation of approximately {{convert|6,880|ft|m}}, and the metropolitan area's highest point is ] at an altitude of {{convert|10,678|ft|m}}. | |||

| According to the ], Albuquerque has a total area of <span style="white-space:nowrap">{{convert|490.9|sqkm|order=flip}}</span>, of which <span style="white-space:nowrap">{{convert|486.2|km2|order=flip}}</span> is land and <span style="white-space:nowrap">{{convert|4.7|km2|order=flip}}</span>, or 0.96%, is water.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/DEC/10_DP/G001/1600000US3502000 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20200212191210/http://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/DEC/10_DP/G001/1600000US3502000 |archive-date=February 12, 2020 |title=Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Albuquerque city, New Mexico |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder |access-date=January 27, 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| Albuquerque has one of the highest elevations of any major city in the United States, though the effects of this are greatly tempered by its southwesterly continental position. The elevation of the city ranges from <span style="white-space:nowrap">4,900 feet (1,490 m)</span> above sea level near the Rio Grande (in the Valley) to over <span style="white-space:nowrap">6,700 feet (1,950 m)</span> in the foothill areas of Sandia Heights and Glenwood Hills. At the airport, the elevation is <span style="white-space:nowrap">5,352 feet (1,631 m)</span> above sea level. | |||

| Albuquerque lies within the fertile ] with its ] forest, in the center of the ], flanked on the eastern side by the ] and to the west by the ].<ref name=lcalabre> | |||

| {{cite web |title=Vegetation & The Environment in NM |url=http://www.unm.edu/~lcalabre/project/ |author=Laura Calabrese |publisher=University of New Mexico |access-date=July 24, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131211155214/http://www.unm.edu/~lcalabre/project/ |archive-date=December 11, 2013 }}</ref><ref name=ausherman>{{cite book |title=60 Hikes Within 60 Miles: Albuquerque: Including Santa Fe, Mount Taylor, and San Lorenzo Canyon |edition=2nd |author=Stephen Ausherman |publisher=Menasha Ridge Press |year=2012 |isbn=9780897326001 |page=288 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MGAAynl9q0kC&pg=PA288 |access-date=November 12, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160204194401/https://books.google.com/books?id=MGAAynl9q0kC&pg=PA288&lpg=PA288 |archive-date=February 4, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> Located in central New Mexico, the city also has noticeable influences from the adjacent ] semi-desert, New Mexico Mountains forested with juniper and pine, and Southwest plateaus and plains steppe ecoregions, depending on where one is located. | |||

| ===Landforms and drainage=== | |||

| Albuquerque is located at {{coord|35|6|39|N|106|36|36|W|city}} (35.110703, -106.609991).{{GR|1}} | |||

| Albuquerque has one of the highest and most varied elevations of any major city in the United States, though the effects of this are greatly tempered by its southwesterly continental position.{{Citation needed|date=June 2024|reason=Specifically for effect of southwestern continental position.}} The elevation of the city ranges from <span style="white-space:nowrap">4,949 feet (1,508 m)</span> ] near the Rio Grande<ref>{{Cite web |title=Rio Grande at Albuquerque, NM - USGS Water Data for the Nation |url=https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/08330000/all-graphs/#period=P7D |access-date=June 19, 2024 |website=waterdata.usgs.gov |archive-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240619162242/https://waterdata.usgs.gov/monitoring-location/08330000/all-graphs/#period=P7D |url-status=live }}</ref> (in the Valley) to <span style="white-space:nowrap">6,165 feet (1,879 m)</span> in the foothill areas of ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Geographic Names Information System |url=https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/gaz-record/2584202 |access-date=June 19, 2024 |website=edits.nationalmap.gov |archive-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240619162241/https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/gaz-record/2584202 |url-status=live }}</ref> At the ], the elevation is <span style="white-space:nowrap">5,355 feet (1,632 m)</span> above sea level.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Facts & Figures |url=https://www.abqsunport.com/facts-figures/#:~:text=sunport%20facilities&text=ABQ's%20elevation%20is%205%2C355%20feet,106%20degrees%2C%2037%20minutes%20West. |access-date=June 19, 2024 |website=Albuquerque International Sunport |archive-date=June 19, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240619162251/https://www.abqsunport.com/facts-figures/#:~:text=sunport%20facilities&text=ABQ's%20elevation%20is%205%2C355%20feet,106%20degrees%2C%2037%20minutes%20West. |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Rio Grande is classified, like the ], as an "exotic" river. The New Mexico portion of the Rio Grande lies within the ] Valley, bordered by a system of ]s, including those that lifted up the adjacent ] and ], while lowering the area where the life-sustaining Rio Grande now flows.{{citation needed|date=November 2024}} | |||

| ===Geology and Ecology=== | |||

| {{main|Albuquerque Basin}} | |||

| Albuquerque lies in the ], a portion of the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/resources/water/projects/Albuquerque_basin.html |title=Albuquerque Basin |publisher=The New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources |access-date=September 28, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121107124156/http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/resources/water/projects/Albuquerque_basin.html |archive-date=November 7, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] are the predominant geographic feature visible in Albuquerque. ''Sandía'' is Spanish for "]", and is popularly believed to be a reference to the brilliant pink and green coloration of the mountains at sunset. The pink is due to large exposures of ] cliffs, and the green is due to large swaths of ] forests. However, Robert Julyan notes in ''The Place Names of New Mexico'', "the most likely explanation is the one believed by the ] Indians: the Spaniards, when they encountered the Pueblo in 1540, called it Sandia, because they thought the squash growing there were watermelons, and the name Sandia soon was transferred to the mountains east of the pueblo."<ref name="julyan">Robert Julyan, ''The Place Names of New Mexico'' (revised edition), UNM Press, 1998.</ref> He also notes that the Sandia Pueblo Indians call the mountain ''Bien Mur'', "Big Mountain."<ref name="julyan"/> | |||

| Albuquerque lies at the northern edge of the ] transitioning into the ]. The Sandia Mountains represent the northern edge of the ]. | |||

| The environments of Albuquerque include the Rio Grande ], (floodplain cottonwood forest), arid scrub, and mesas that turn into the Sandia foothills in the east. The Rio Grande's bosque has been significantly reduced and its natural flood cycle disrupted by dams built further upstream. A corridor of bosque surrounding the river within the city has been preserved as ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| A few remaining natural arroyos provide riparian habitat within the city, though natural ] draining into the Rio Grande have largely been replaced with concrete channels. After a series of floods in the 1950s, passage of the "Arroyo Flood Control Act of 1963" provided for the construction of a series of concrete diversion channels.<ref name="AMAFCA">{{cite book |last1=Swinburne |first1=Bernard H. |title=Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Flood Control Authority |date=July 1974 |publisher=Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Flood Control Authority |location=Albuquerque |pages=6–8 |url=https://amafca.org/documents/AMAFCABrochureweb.pdf |access-date=October 1, 2024 |archive-date=October 1, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20241001005353/https://amafca.org/documents/AMAFCABrochureweb.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The network of channels was built by the Army Corps of Engineers during the 1960s and early 1970s.<ref name="AMAFCA" /> | |||

| Iconic urban wildlife includes the ], ], ], and ] lizard. The bosque is a popular destination for wildlife viewing, with opportunities to see ] and ]s in the winter.<ref>{{Cite web |title=City of Albuquerque Critters |url=https://www.cabq.gov/parksandrecreation/open-space/city-of-albuquerque-critters |access-date=March 20, 2024 |website=City of Albuquerque |language=en |archive-date=March 20, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240320052718/https://www.cabq.gov/parksandrecreation/open-space/city-of-albuquerque-critters |url-status=live }}</ref> ] are common in city parks.<ref>{{Cite web |date=August 6, 2019 |title=Cooper's hawk population booming in Albuquerque |url=https://www.krqe.com/news/albuquerque-metro/coopers-hawk-population-booming-in-albuquerque/ |access-date=March 20, 2024 |website=KRQE NEWS 13 - Breaking News, Albuquerque News, New Mexico News, Weather, and Videos |language=en-US }}</ref> | |||

| Iconic vegetation includes the ] in the bosque, and ], ], ], ], and ] in upland areas. The foothill open space at the eastern border also features ] and ]. ]s are commonly planted throughout the city. ] are a common weed in disturbed areas, and are used by the city to make an annual holiday snowman.<ref>{{Cite web |title=AMAFCA Tumbleweed Snowman |url=https://amafca.org/snowman-tumbleweed/ |access-date=March 20, 2024 |website=AMAFCA |language=en-US |archive-date=March 20, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240320052719/https://amafca.org/snowman-tumbleweed/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Cityscape=== | |||

| {{wide image|Albuquerque_pano_sunset.jpg|1500px|align-cap=center|Panoramic view of the city of Albuquerque looking east}} | |||

| ] upper terminal</div>]] | |||

| ====Quadrants==== | |||

| Albuquerque is geographically divided into four unequal ] that are officially part of mailing addresses, placed immediately after the street name. They are Northeast (NE), Northwest (NW), Southeast (SE), and Southwest (SW). Albuquerque's official quadrant system uses Central Ave for the north–south division and the railroad tracks for the east–west division. I-25 and I-40 are also sometimes used informally to divide the city into quadrants. | |||

| =====Northeast===== | |||

| This quadrant has been experiencing a housing expansion since the late 1950s. It abuts the base of the Sandia Mountains and contains portions of the foothills neighborhoods, which are significantly higher in elevation than the rest of the city. Running from Central Ave and the ] tracks to the ], this is the largest quadrant both geographically and by population. Martineztown, the ], ], the Uptown area, which includes three shopping malls (], ABQ Uptown, and ]), Hoffmantown, Journal Center, and ] are all in this quadrant. | |||

| Some of the most affluent neighborhoods in the city are here, including: ], Tanoan, Sandia Heights, and North Albuquerque Acres. Parts of Sandia Heights and North Albuquerque Acres are outside the city limits proper. A few houses in the farthest reach of this quadrant lie in the ], just over the line into ]. | |||

| =====Northwest===== | |||

| ] in Downtown]] | |||

| This quadrant contains historic ], which dates to the 18th century, as well as the ]. The area has a mixture of commercial districts and low to high-income neighborhoods. Northwest Albuquerque includes the largest section of ], ] and the ] ("woodlands"), Petroglyph National Monument, ], the Paradise Hills neighborhood, Taylor Ranch, and ]. | |||

| This quadrant also contains the ] settlement, outside the city limits, which has some expensive homes and small ranches along the ]. The city of Albuquerque engulfs the village of ]. A small portion of the rapidly developing area on the west side of the river south of the Petroglyphs, known as the "]" or "Westside", consisting primarily of traditional residential subdivisions, also extends into this quadrant. The city proper is bordered on the north by the North Valley, the village of ], and the city of ]. | |||

| =====Southeast===== | |||

| ] in Nob Hill]] | |||

| ], ], Sandia Science & Technology Park, the Max Q commercial district, ], ], ], ], Presbyterian Hospital Duke City BMX, ], ], ], ], ], ], Isleta Resort & Casino, the ], New Mexico Veterans Memorial, and {{not a typo|Talin}}<!-- typo correction wants to correct this to Tallinn, capital of Estonia--> Market are all located in the Southeast quadrant of Albuquerque. | |||

| The southern half of the International District lies along Central Ave and Louisiana Blvd. Here, many immigrant communities have settled and thrive, having established numerous businesses.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} Albuquerque's ] community is partly business-centered in this area, as well as the Eubank, Juan Tabo, and Central areas, and other parts of Albuquerque. There is also a ] temple and a sizable community in parts of this area as well as around Uptown. There is also an African American community around Highland.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| The Four Hills neighborhoods are located in and around the foothills on the outskirts of Southeast Albuquerque. The vast newer subdivision of Volterra lies west of the Four Hills area. Popular urban neighborhoods that can be found in Southeast Albuquerque include ], Ridgecrest, Parkland Hills, Hyder Park, and University Heights. | |||

| =====Southwest===== | |||

| Traditionally consisting of agricultural and rural areas and suburban neighborhoods, the Southwest quadrant comprises the south-end of Downtown Albuquerque, the ] neighborhood, the rapidly growing west side, and the community of ], often called "The South Valley". The quadrant extends all the way to the Isleta Indian Reservation. Newer suburban subdivisions on the ] near the southwestern city limits join homes of older construction, some dating as far back as the 1940s.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} This quadrant includes the old communities of Atrisco, Los Padillas, Huning Castle, Kinney, Westgate, Westside, Alamosa, Mountainview, and Pajarito. The Bosque ("woodlands"), the ], the ], and ] are also here. | |||

| A new adopted development plan, the Santolina Master Plan, will extend development on the west side past 118th Street SW to the edge of the ] and house 100,000 by 2050.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bernco.gov/planning/proposed-santolina-level-a-master-plan.aspx |title=Adopted Santolina Level A Master Plan-Bernalillo County, New Mexico |work=bernco.gov |access-date=September 5, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160907040938/http://www.bernco.gov/planning/proposed-santolina-level-a-master-plan.aspx |archive-date=September 7, 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Climate=== | ===Climate=== | ||

| {{climate chart | |||

| Albuquerque's climate is classified as a ] (''BSk'') according to the ] system, while The Biota of North America Program<ref>{{Cite web |title=Climate |url=http://www.bonap.org/Climate%20Maps/climate48shadeA.png |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171124115104/http://www.bonap.org/Climate%20Maps/climate48shadeA.png |archive-date=November 24, 2017 |access-date=May 2, 2019 }}</ref> and the U.S. Geological Survey describe it as warm temperate semi-desert.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3084/ |title=USGS Scientific Investigations Map 3084: Terrestrial Ecosystems—Isobioclimates of the Conterminous United States |website=pubs.usgs.gov |access-date=April 13, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190901232200/https://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3084/ |archive-date=September 1, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://prism.oregonstate.edu/ |title=PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State U |website=prism.oregonstate.edu |access-date=April 13, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200122024305/http://prism.oregonstate.edu/ |archive-date=January 22, 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| |] | |||

| |24|48|.49 | |||

| {{Weather box | |||

| |28|55|.44 | |||

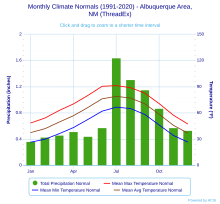

| |location = Albuquerque (]), 1991–2020 normals,{{efn|Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.}} extremes 1891–present{{efn|Official records for Albuquerque kept December 1891 to January 22, 1933, at the Weather Bureau Office and at Albuquerque Int'l since January 23, 1933. For more information, see Threadex}} | |||

| |34|62|.61 | |||

| |single line = Y | |||

| |41|71|.50 | |||

| |collapsed = | |||

| |50|80|.60 | |||

| |Jan record high F = 72 | |||

| |59|90|.65 | |||

| |Feb record high F = 79 | |||

| |65|92|1.27 | |||

| |Mar record high F = 85 | |||

| |63|89|1.73 | |||

| |Apr record high F = 89 | |||

| |56|82|1.07 | |||

| |May record high F = 98 | |||

| |44|71|1.00 | |||

| |Jun record high F = 107 | |||

| |32|57|.62 | |||

| |Jul record high F = 105 | |||

| |24|48|.49 | |||

| |Aug record high F = 102 | |||

| |source=Weather.com / NWS | |||

| |Sep record high F = 100 | |||

| |float=right | |||

| |Oct record high F = 91 | |||

| |clear=left | |||

| |Nov record high F = 83 | |||

| |units=imperial | |||

| |Dec record high F = 72 | |||

| |Jan avg record high F = 60.9 | |||

| |Feb avg record high F = 67.5 | |||

| |Mar avg record high F = 76.8 | |||

| |Apr avg record high F = 83.2 | |||

| |May avg record high F = 91.2 | |||

| |Jun avg record high F = 99.3 | |||

| |Jul avg record high F = 99.4 | |||

| |Aug avg record high F = 96.1 | |||

| |Sep avg record high F = 91.7 | |||

| |Oct avg record high F = 83.6 | |||

| |Nov avg record high F = 71.1 | |||

| |Dec avg record high F = 60.8 | |||

| |year avg record high F = 100.8 | |||

| |Jan high F = 48.4 | |||

| |Feb high F = 54.1 | |||

| |Mar high F = 62.8 | |||

| |Apr high F = 70.3 | |||

| |May high F = 79.9 | |||

| |Jun high F = 90.4 | |||

| |Jul high F = 91.2 | |||

| |Aug high F = 88.8 | |||

| |Sep high F = 82.5 | |||

| |Oct high F = 70.6 | |||

| |Nov high F = 57.3 | |||

| |Dec high F = 47.3 | |||

| |year high F = 70.3 | |||

| |Jan mean F = 37.4 | |||

| |Feb mean F = 41.9 | |||

| |Mar mean F = 49.5 | |||

| |Apr mean F = 56.8 | |||

| |May mean F = 66.1 | |||

| |Jun mean F = 76.1 | |||

| |Jul mean F = 78.9 | |||

| |Aug mean F = 76.9 | |||

| |Sep mean F = 70.3 | |||

| |Oct mean F = 58.4 | |||

| |Nov mean F = 45.7 | |||

| |Dec mean F = 36.9 | |||

| |year mean F = 57.9 | |||

| |Jan low F = 26.4 | |||

| |Feb low F = 29.8 | |||

| |Mar low F = 36.2 | |||

| |Apr low F = 43.2 | |||

| |May low F = 52.4 | |||

| |Jun low F = 61.9 | |||

| |Jul low F = 66.5 | |||

| |Aug low F = 64.9 | |||

| |Sep low F = 58.1 | |||

| |Oct low F = 46.1 | |||

| |Nov low F = 34.1 | |||

| |Dec low F = 26.6 | |||

| |year low F = 45.5 | |||

| |Jan avg record low F = 15.4 | |||

| |Feb avg record low F = 17.6 | |||

| |Mar avg record low F = 23.9 | |||

| |Apr avg record low F = 30.5 | |||

| |May avg record low F = 39.6 | |||

| |Jun avg record low F = 52.3 | |||

| |Jul avg record low F = 60.6 | |||

| |Aug avg record low F = 59.0 | |||

| |Sep avg record low F = 47.4 | |||

| |Oct avg record low F = 31.9 | |||

| |Nov avg record low F = 21.3 | |||

| |Dec avg record low F = 13.7 | |||

| |year avg record low F = 10.9 | |||

| |Jan record low F = −17 | |||

| |Feb record low F = −10 | |||

| |Mar record low F = 6 | |||

| |Apr record low F = 13 | |||

| |May record low F = 25 | |||

| |Jun record low F = 35 | |||

| |Jul record low F = 42 | |||

| |Aug record low F = 46 | |||

| |Sep record low F = 26 | |||

| |Oct record low F = 19 | |||

| |Nov record low F = −7 | |||

| |Dec record low F = −16 | |||

| |precipitation colour = green | |||

| |Jan precipitation inch = 0.36 | |||

| |Feb precipitation inch = 0.43 | |||

| |Mar precipitation inch = 0.46 | |||

| |Apr precipitation inch = 0.51 | |||

| |May precipitation inch = 0.44 | |||

| |Jun precipitation inch = 0.57 | |||

| |Jul precipitation inch = 1.64 | |||

| |Aug precipitation inch = 1.31 | |||

| |Sep precipitation inch = 1.15 | |||

| |Oct precipitation inch = 0.87 | |||

| |Nov precipitation inch = 0.57 | |||

| |Dec precipitation inch = 0.53 | |||

| |year precipitation inch = 8.84 | |||

| |Jul snow inch = 0.0 | |||

| |Aug snow inch = 0.0 | |||

| |Sep snow inch = 0.0 | |||

| |Oct snow inch = 0.3 | |||

| |Nov snow inch = 0.9 | |||

| |Dec snow inch = 2.8 | |||

| |Jan snow inch = 1.4 | |||

| |Feb snow inch = 1.5 | |||

| |Mar snow inch = 0.7 | |||

| |Apr snow inch = 0.3 | |||

| |May snow inch = 0.0 | |||

| |Jun snow inch = 0.0 | |||

| |year snow inch = 7.9 | |||

| |unit precipitation days = 0.01 in | |||

| |Jan precipitation days = 3.6 | |||

| |Feb precipitation days = 3.7 | |||

| |Mar precipitation days = 3.8 | |||

| |Apr precipitation days = 2.8 | |||

| |May precipitation days = 3.7 | |||

| |Jun precipitation days = 3.5 | |||

| |Jul precipitation days = 8.7 | |||

| |Aug precipitation days = 8.3 | |||

| |Sep precipitation days = 5.9 | |||

| |Oct precipitation days = 4.7 | |||

| |Nov precipitation days = 3.4 | |||

| |Dec precipitation days = 4.0 | |||

| |year precipitation days = 56.1 | |||

| |unit snow days = 0.1 in | |||

| |Jul snow days = 0.0 | |||

| |Aug snow days = 0.0 | |||

| |Sep snow days = 0.0 | |||

| |Oct snow days = 0.3 | |||

| |Nov snow days = 0.9 | |||

| |Dec snow days = 2.5 | |||

| |Jan snow days = 1.9 | |||

| |Feb snow days = 1.6 | |||

| |Mar snow days = 1.0 | |||

| |Apr snow days = 0.3 | |||

| |May snow days = 0.0 | |||

| |Jun snow days = 0.0 | |||

| |year snow days = 8.5 | |||

| |Jan sun = 234.2 |Jan percentsun = 75 | |||

| |Feb sun = 225.3 |Feb percentsun = 74 | |||

| |Mar sun = 270.2 |Mar percentsun = 73 | |||

| |Apr sun = 304.6 |Apr percentsun = 78 | |||

| |May sun = 347.4 |May percentsun = 80 | |||

| |Jun sun = 359.3 |Jun percentsun = 83 | |||

| |Jul sun = 335.0 |Jul percentsun = 76 | |||

| |Aug sun = 314.2 |Aug percentsun = 75 | |||

| |Sep sun = 286.7 |Sep percentsun = 77 | |||

| |Oct sun = 281.4 |Oct percentsun = 80 | |||

| |Nov sun = 233.8 |Nov percentsun = 75 | |||

| |Dec sun = 223.3 |Dec percentsun = 73 | |||

| |year percentsun = 77 | |||

| |Jan humidity = 56.3 | |||

| |Feb humidity = 49.8 | |||

| |Mar humidity = 39.7 | |||

| |Apr humidity = 32.5 | |||

| |May humidity = 31.1 | |||

| |Jun humidity = 29.8 | |||

| |Jul humidity = 41.9 | |||

| |Aug humidity = 47.1 | |||

| |Sep humidity = 47.4 | |||

| |Oct humidity = 45.3 | |||

| |Nov humidity = 49.9 | |||

| |Dec humidity = 56.8 | |||

| |year humidity = 44.0 | |||

| |Jan dew point C = −7.8 | |||

| |Feb dew point C = −6.9 | |||

| |Mar dew point C = −7.1 | |||

| |Apr dew point C = −5.9 | |||

| |May dew point C = −2.3 | |||

| |Jun dew point C = 1.9 | |||

| |Jul dew point C = 9.5 | |||

| |Aug dew point C = 10.2 | |||

| |Sep dew point C = 6.7 | |||

| |Oct dew point C = 0.3 | |||

| |Nov dew point C = −4.6 | |||

| |Dec dew point C = −7.2 | |||

| |source 1 = NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)<ref name = NOAA1 >{{cite web |url=https://w2.weather.gov/climate/xmacis.php?wfo=abq |title=NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data |publisher=] |access-date=October 13, 2021 |archive-date=April 30, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210430063248/https://w2.weather.gov/climate/xmacis.php?wfo=abq |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NCEI Summary of Monthly Normals - Albuquerque - 1991-2020">{{cite web |url=https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/services/data/v1?dataset=normals-monthly-1991-2020&startDate=0001-01-01&endDate=9996-12-31&stations=USW00023050&format=pdf |title=Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020 |publisher=] |access-date=October 13, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230714063557/https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/services/data/v1?dataset=normals-monthly-1991-2020&startDate=0001-01-01&endDate=9996-12-31&stations=USW00023050&format=pdf |archive-date=July 14, 2023 }}</ref><ref name= noaasun >{{cite web |url=ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG_IV/US/GROUP3/72365.TXT |title=WMO Climate Normals for ALBUQUERQUE/INT'L ARPT NM 1961–1990 |access-date=August 29, 2020 |publisher=National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230714060206/ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG_IV/US/GROUP3/72365.TXT |archive-date=July 14, 2023 }}</ref><!--<ref name = "Percent Sunshine" > | |||

| {{cite web |url=http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/pctpos.txt |title=Average Percent Sunshine through 2009 |access-date=November 16, 2012 |publisher=] }}</ref>--> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Weather box | |||

| Albuquerque's climate is usually sunny and dry, with low relative humidity. Brilliant sunshine defines the region, averaging more than 300 days a year; periods of variably mid and high-level cloudiness temper the sun at other times. Extended cloudiness is rare. The city has four distinct seasons, but the heat and cold are mild compared to the extremes that occur more commonly in other parts of the country. | |||

| |location =] (elevation {{cvt|1510.3|m|order=flip}}, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1991–2022) | |||

| |single line = Y | |||

| |collapsed = Y | |||

| |Jan record high F = 73 | |||

| |Feb record high F = 79 | |||

| |Mar record high F = 86 | |||

| |Apr record high F = 89 | |||

| |May record high F = 101 | |||

| |Jun record high F = 105 | |||

| |Jul record high F = 104 | |||

| |Aug record high F = 101 | |||

| |Sep record high F = 98 | |||

| |Oct record high F = 89 | |||

| |Nov record high F = 79 | |||