| Revision as of 03:23, 29 January 2009 view sourceFl (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,570 editsm →Ancient: rm clear, + {{fact}}← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:41, 3 January 2025 view source MRTFR55 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,453 edits Rescuing 23 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.9.5Tag: IABotManagementConsole [1.3] | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Distinct territorial body or political entity}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Hatnote group| | |||

| ] map]] | |||

| {{Distinguish|County}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{About||countryside|Rural area|other uses}} | |||

| '''Country''' ({{IPA-en|ˈkən-trē}}<ref>{{cite encyclopedia| encyclopedia = Merriam-Webster Dictionary| title = country| url = http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Country| accessdate = 2008-12-01| edition = 2008}}</ref>) may refer to the territory of a ], or sometimes to a smaller, or former, ] of a geographical region. In another meaning of the word, the '''country''' (or ]) is also a term used to refer to ]. Usually, but not always, a country coincides with a ] and is associated with a ], ] and ]. | |||

| }} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}}{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}}{{Use American English|date=August 2022}} | |||

| ]s with full international recognition (brackets denote the country of a marked territory that is not a sovereign state). Some territories are countries in their own right but are ] (e.g. ]), and some few marked territories are ] about which country they belong to (e.g. ]) or if they are countries in their own right (e.g. ] (territory) or ]).]] | |||

| In common usage, the term country is widely in the sense of both nations and states, with definitions varying. In some cases it is used to refer both to states and to other political entities,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/aia1901230/s22.html |title=Acts Interpretation Act 1901 - Sect 22: Meaning of certain words |publisher=Australasian Legal Information Institute |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/disp.pl/au/cases/cth/federal%5fct/1997/912.html |title=The Kwet Koe v Minister for Immigration & Ethnic Affairs & Ors [1997] FCA 912 (8 September 1997) |publisher=Australasian Legal Information Institute |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/84411.pdf |title=U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 2—General |format=PDF |publisher=United States Department of State |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref> while in some occasions it refers only to states<ref>{{cite web|url=http://geography.about.com/cs/politicalgeog/a/statenation.htm| title=Geography: Country, State, and Nation |accessdate=2008-11-12 |last=Rosenberg |first=Matt}}</ref> It is not uncommon for general information or statistical publications to adopt the wider definition for purposes such as illustration and comparison.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countryreports.org/country.aspx?countryid=96&countryName=countryid=96&countryName=Greenland |title=Greenland Country Information |publisher=Countryreports.org |accessdate=2008-5-28 web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2078rank.html |title=The World Factbook - Rank Order - Exports |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritage.org/index/countries.cfm |title=Index of Economic Freedom |publisher=The Heritage Foundation |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/topten.cfm |title=Index of Economic Freedom - Top 10 Countries |publisher=The Heritage Foundation |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.heritage.org/research/features/index/chapters/pdf/index2007_RegionA_Asia-Pacific.pdf |title=Asia-Pacific (Region A) Economic Information |format=PDF |publisher=The Heritage Foundation |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://umich.edu/news/happy_08/HappyChart.pdf |title=Subjective well-being in 97 countries |format=PDF |publisher=University of Michigan |accessdate=2008-11-12}}</ref> | |||

| A '''country''' is a distinct part of the ], such as a ], ], or other ]. When referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a ], ], ], or a ].<ref name="Fowler Bunck 1996 pp. 381–404"/><ref name="World Population by Country 2024 (Live) 1945 w673"/><ref name="academic.oup.com i784"/><ref>{{cite journal |last=Jones |first=J |date=1964 |title=What Makes a Country? |journal=Human Events |volume=24 |issue=31 |page=14}}</ref> Most sovereign states, but not all countries, are members of the ].<ref name="World Population by Country 2024 (Live) z997"/> There is no universal agreement on the number of "countries" in the world since several states have disputed sovereignty status, limited recognition and a number of non-sovereign entities are commonly considered countries.<ref name="Seguin 2011 f032"/><ref name="World Population by Country 2024 (Live) z997"/> | |||

| Some entities which constitute cohesive geographical entities, and may be former states, but which are not presently sovereign states (such as ], ] and ]), are commonly regarded and referred to as countries. Another example is the ], which has a number of possible meanings, but none coinciding with the borders of a state. Here it is the distinctiveness of the ] nation which has preserved the use of the word; other former states such as ] (now part of Germany) and ] (now part of Italy) would not normally be referred to as "countries" in English. The degree of autonomy of such non-state countries varies widely. Some are possessions of states, as several states have overseas ] (such as the ], ], and ]), with territory and citizenry distinct from their own. Such dependent territories are sometimes listed together with independent states on lists of countries. | |||

| The definition and usage of the word "country" are flexible and have changed over time. '']'' wrote in 2010 that "any attempt to find a clear definition of a country soon runs into a thicket of exceptions and anomalies."<ref>{{Cite news |date=8 April 2010 |title=In quite a state |newspaper=] |url=https://www.economist.com/international/2010/04/08/in-quite-a-state |access-date=2022-08-24 |issn=0013-0613 |archive-date=24 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220824202226/https://www.economist.com/international/2010/04/08/in-quite-a-state |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In ancient history, ] did not have definite boundaries as countries have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as ]s. ], and ] were the first civilizations to define their ]s. | |||

| <!-- | |||

| Commented out for now, this paragraph is hard to understand, pending rewrite | |||

| There are non-] territories (subnational entities, another form of political division or ] within a larger nation-state) which constitute cohesive geographical entities, some of which are former states, but which are not presently sovereign states. Some are commonly designated as countries (e.g. ], ] and ]), while others are not (e.g., ], ] and ]). The degree of autonomy and local government varies widely. Some are possessions of states, as several states have overseas ] (e.g., the ], ], and ]), with territory and citizenry separate from their own. Such dependent territories are sometimes listed together with states on lists of countries. | |||

| --> | |||

| Areas much smaller than a political entity may be referred to as a "country", such as the ] in England, "big sky country" (used in various contexts of the ]), "coal country" (used to describe ]s), or simply "the country" (used to describe a ]).<ref name="oed"/><ref name="Merriam-Webster 2024 u184">{{cite web | title=Definition of COUNTRY | website=Merriam-Webster | date=2024-02-29 | url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/country | access-date=2024-03-02 | archive-date=5 August 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220805032115/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/country | url-status=live }}</ref> The term "country" is also used as a qualifier descriptively, such as ] or ].<ref name="Cambridge Dictionary 2024 t399">{{cite web | title=country | website=Cambridge Dictionary | date=2024-02-28 | url=https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/country | access-date=2024-03-02 | archive-date=26 March 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240326084006/https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/country | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology and development of the word== | |||

| Country has developed from the ] ''contra'', meaning "against", used in the sense of "that which lies against, or opposite to, the view", i.e. the landscape spread out to the view. From this came the ] term ''contrata'', which became the modern ] '']''. The term appears in ] from the 13th century, already in several different senses.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia| editor = John Simpson, Edmund Weiner | encyclopedia = Oxford English Dictionary| edition = 1971 compact | publisher = Oxford University Press| location = Oxford, England| isbn = 0198611862 |title = country | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| In English the word has increasingly become associated with political divisions, so that one sense, associated with the ] - "a country" - is now a ] for ], in the sense of sovereign territory, for example in the phrase "]". But several other senses of the word remain, including "country" as the opposite of "town", a term for ] areas in general, as in ]. This is used with a generalized ] - "the country". Areas much smaller than a political state may be called by names such as the ] in England, the ] (a heavily industrialized part of England), "Constable Country" (a part of ] painted by ], the "big country" (used in various contexts of the ]), "coal country" (used of parts of the US and elsewhere) and many other terms.<ref name="oed">{{cite encyclopedia| editor = John Simpson, Edmund Weiner | encyclopedia = Oxford English Dictionary| edition = 1971 compact | publisher = Oxford University Press| location = Oxford, England| isbn = 0198611862 | |||

| The word ''country'' comes from ] {{lang|fro|contrée}}, which derives from ] ({{lang|la|terra}}) {{lang|la|contrata}} ("(land) lying opposite"; "(land) spread before"), derived from {{lang|la|contra}} ("against, opposite"). It most likely entered the English language after the ] during the 11th century.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Definition of COUNTRY |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/country |access-date=2022-08-25 |website=Merriam-Webster |language=en |archive-date=5 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220805032115/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/country |url-status=live }}</ref>{{Better source needed|reason=The current source is tertiary|date=February 2023}} | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == Definition of a country == | |||

| The equivalent terms in French and other ]s (''pays'' and variants) and the ]s (''land'' and variants) have not carried the process of being identified with political sovereign states as far as the English "country", and in many European countries the words are used for sub-divisions of the national territory, as in the ], as well as a less formal term for a sovereign state. France has very many "pays" that are officially recognised at some level, and are either ]s, like the ], or reflect old political or economic unities, like the ]. At the same time the United States and Brazil are also "pays" in everyday French speech. | |||

| In English the word has increasingly become associated with political divisions, so that one sense, associated with the ] – "a country" – is now frequently applied as a synonym for a state or a former sovereign state. It may also be used as a synonym for "nation". Taking as examples ], ], and ], cultural anthropologist ] wrote in 1997 that "it is clear that the relationships between 'country' and 'nation' are so different from one to the next as to be impossible to fold into a dichotomous opposition as they are into a promiscuous fusion."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Geertz |first=Clifford |date=1997 |title=What is a Country if it is Not a Nation? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24590031 |journal=The Brown Journal of World Affairs |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=235–247 |jstor=24590031 |issn=1080-0786}}</ref> | |||

| Although a version of "country", as ''cuntrée'', existed in ],<ref name="oed" /> it has not survived into the modern language, whereas the modern Italian ''contrada'' is a word with its meaning varying locally, but usually meaning a ] or similar small division of a town, or a village or hamlet in the countryside. | |||

| Areas much smaller than a political state may be referred to as countries, such as the ] in England, "big sky country" (used in various contexts of the ]), "coal country" (used to describe ]s in several sovereign states) and many other terms.<ref name="oed">{{cite encyclopedia |title=country, n. |editor-first1=John |editor-last1=Simpson |editor-first2=Edmund |editor-last2=Weiner |encyclopedia=] |edition=1971 compact |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford, England |isbn=978-0-19-861186-8}}</ref> The word "country" is also used for the sense of ], such as the widespread use of ] in the United States.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Matal |first=Joseph |date=1997-12-01 |title=A Revisionist History of Indian Country |url=https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/alr/vol14/iss2/1 |journal=Alaska Law Review |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=283–352 |issn=0883-0568 |access-date=19 October 2022 |archive-date=11 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230111202441/https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/alr/vol14/iss2/1/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The term "country" in English may also be wielded to describe ]s, or used in the form "countryside." ], a Welsh scholar, wrote in 1975:<ref>{{Cite book |last=Williams |first=Raymond |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/624711 |title=The country and the city |date=1973 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0-19-519736-4 |location=New York |oclc=624711 |access-date=23 August 2022 |archive-date=27 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220827204730/https://www.worldcat.org/title/624711 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Ancient=== | |||

| {{main|Ancient history}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <!-- Reference, may be useful later on <ref name="ancienttimeline">{{cite book |last=Baigent |first=Michael |authorlink=Michael Baigent |title=Ancient Traces: Mysteries in Ancient and Early History |date=1998 |publisher=Penguin Group |isbn=067087454X |pages=117–119 |chapter=Where Did Our Civilization Come From?}}</ref> | |||

| {{Block quote|text='Country' and 'city' are very powerful words, and this is not surprising when we remember how much they seem to stand for in the experience of human communities. In English, 'country' is both a nation and a part of a 'land'; 'the country' can be the whole society or its rural area. In the long history of human settlements, this connection between the land from which directly or indirectly we all get our living and the achievements of human society has been deeply known.|author=|title=|source=}} | |||

| -->The first countries of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the ] and ] respectively at approximately 3000BC.<ref name="ancientlocations">{{cite book |last=Daniel |first=Glyn |authorlink=Glyn Daniel |title=The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins |origyear=1968 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wx9FAAAAMAAJ |format=HTML |year=2003 |publisher=Phoenix Press |location=New York |isbn=1842125001 |pages=xiii |nopp=true}}</ref> Early dynastic ] was based around the ] in the north-east of ], the country's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where ] existed.<ref>{{cite book |last=Daniel |first=Glyn |authorlink=Glyn Daniel |title=The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins |origyear=1968 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wx9FAAAAMAAJ |format=HTML |year=2003 |publisher=Phoenix Press |location=New York |isbn=1842125001 |pages=9–11}}</ref> Early dynastic ] was located in southern ] with its borders extending from the ] to parts of the ] and ] ].<ref name="ancientlocations"/> | |||

| The unclear definition of "country" in modern English was further commented upon by philosopher ]:<ref>{{Cite book |last=Keller |first=Simon |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/441874932 |title=New waves in political philosophy |date=2009 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-0-230-23499-4 |editor-last=De Bruin |editor-first=Boudewijn |location=Basingstoke, England |pages=96 |chapter=Making Nonsense of Loyalty to Country |oclc=441874932 |editor-last2=Zurn |editor-first2=Christopher F. |access-date=23 August 2022 |archive-date=27 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220827204729/https://www.worldcat.org/title/441874932 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| By 2500 BCE the Indian civilization, located in the ] had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended 600KM inland from the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Daniels |first=Patrica S |coauthors=Stephen G Hyslop, Douglas Brinkley, Esther Ferington, Lee Hassig, Dale-Marie Herring |editor=Toni Eugene |title=Almanac of World History |year=2003 |publisher=National Geographic Society |isbn=0792250923 |pages=56 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=d5gPAQAACAAJ |format=HTML}}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=Often, a country is presumed to be identical with a collection of citizens. Sometimes, people say that a country is a project, or an idea, or an ideal. Occasionally, philosophers entertain more metaphysically ambitious pictures, suggesting that a country is an organic entity with its own independent life and character, or that a country is an autonomous agent, just like you or me. Such claims are rarely explained or defended, however, and it is not clear how they should be assessed. We attribute so many different kinds of properties to countries, speaking as though a country can feature wheat fields waving or be girt by sea, can have a founding date and be democratic and free, can be English speaking, culturally diverse, war torn or Islamic.|title=''New Waves In Political Philosophy'', "Making Nonsense of Loyalty to Country"|source=page 96}}], an ] writer, expressed the difficulty of defining "country" in a 2005 essay, "Unsettlement":<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lucashenko |first=Melissa |date=2005-01-01 |title=Country: Being and belonging on aboriginal lands |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050509388027 |journal=Journal of Australian Studies |volume=29 |issue=86 |pages=7–12 |doi=10.1080/14443050509388027 |s2cid=143550941 |issn=1444-3058}}</ref> | |||

| 336 BCE saw the rise of ], who forged an empire from various vassal states stretching from modern ] to the Indian subcontinent, bringing Medeterrainian nations into contact with those of central and southern Asia, much as the Persian Empire had before him. The boundaries of this empire extended hundreds of kilometers.<ref>{{cite book| last=de Blois |first=Lukas |coauthor=Robartus van der Spek |title=An Introduction to the Ancient World |year=1997 |publisher=Routledge |location=New York, US |isbn=0415127734 |pages=131 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9o3Ti6H2_BQC}}</ref> | |||

| {{Block quote|text=...What is this thing country? What does country | |||

| mean? ... I spoke with others who said country meant Home, but who added the caveat that Home resided in people rather than places{{snd}}a kind of portable Country... I tried to tease out some ways in which non-Indigenous people have understood country. I made categories: Country as Economy. Country as Geography. Country as Society. Country as Myth. Country as History. For all that I walked, slept, breathed and dreamed Country, the language still would not come.}} | |||

| == Statehood== | |||

| The Roman Empire (509 BCE-476 CE) was the first western civilization known to accurately define their borders, although these borders could be more accurately described as frontiers;<ref>{{cite web |url=http://wrt-intertext.syr.edu/IX/arras.html |title=A World Defined By Boundaries |accessdate=2008-11-21 |work=Intertext |publisher=Syracuse University |year=2001 }}</ref> instead of the Empire defining its borders with precision, the borders were allowed to trail off and were, in many cases, part of territory indirectly ruled by others.<ref>{{cite book |last=Kaplan |first=David H |coauthors=Jouni Häkli |title=Boundaries and Place: European Borderlands in Geographical Context |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=edb-7VL6H0cC |format=HTML |year=2002 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=0847698831 |pages=19 |chapter=The 'Civilisational' Roots of European National Boundaries |chapterurl=http://books.google.com/books?id=edb-7VL6H0cC&pg=PA18&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=0_0}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Sovereign state}} | |||

| {{seealso|List of sovereign states|List of sovereign states and dependent territories by continent|List of states with limited recognition}} | |||

| When referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a ], ], ], or a ].<ref name="Fowler Bunck 1996 pp. 381–404">{{cite journal | last1=Fowler | first1=Michael Ross | last2=Bunck | first2=Julie Marie | title=What constitutes the sovereign state? | journal=Review of International Studies | publisher=Cambridge University Press (CUP) | volume=22 | issue=4 | year=1996 | issn=0260-2105 | doi=10.1017/s0260210500118637 | pages=381–404| s2cid=145809847 }}</ref><ref name="World Population by Country 2024 (Live) 1945 w673">{{cite web | title=Countries Not in the United Nations 2024 | website=World Population by Country 2024 (Live) | date=26 June 1945 | url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-not-in-the-un | access-date=2 March 2024 | archive-date=19 February 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240219170853/https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-not-in-the-un | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="academic.oup.com i784">{{cite web | title=Recognition and its Variants | website=academic.oup.com | url=https://academic.oup.com/book/43016/chapter-abstract/361359523?redirectedFrom=fulltext | access-date=2 March 2024 | archive-date=2 March 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240302214852/https://academic.oup.com/book/43016/chapter-abstract/361359523?redirectedFrom=fulltext | url-status=live }}</ref> A sovereign state is a ] that has supreme legitimate authority over a part of the world.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Philpott |first=Daniel |date=1995 |title=Sovereignty: An Introduction and Brief History |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24357595 |url-status=live |journal=Journal of International Affairs |volume=48 |issue=2 |pages=353–368 |issn=0022-197X |jstor=24357595 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220807105623/https://www.jstor.org/stable/24357595 |archive-date=7 August 2022 |access-date=21 July 2022}}</ref> There is no universal agreement on the number of "countries" in the world since several states have disputed sovereignty status, and a number of non-sovereign entities are commonly called countries.<ref name="World Population by Country 2024 (Live) z997">{{cite web | title=Sovereign Nation 2024 | website=World Population by Country 2024 (Live) | url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/sovereign-nation | access-date=2024-01-21 | archive-date=19 December 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231219015440/http://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/sovereign-nation | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Seguin 2011 f032">{{cite web | last=Seguin | first=Denis | title=What makes a country? | website=The Globe and Mail | date=2011-07-29 | url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/what-makes-a-country/article595868/ | access-date=2024-01-24 | archive-date=24 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240124003740/https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/what-makes-a-country/article595868/ | url-status=live }}</ref> No definition is binding on all the members of the community of nations on the criteria for statehood.<ref name="Bedjaoui 1991 p. 47">{{cite book | last=Bedjaoui | first=M. | title=International Law: Achievements and Prospects | publisher=Springer Netherlands | series=Democracy and power | year=1991 | isbn=978-92-3-102716-1 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jrTsNTzcY7EC&pg=PA47] | access-date=23 January 2024 | page=47]}}</ref><ref name="Seguin 2011 f032"/> State practice relating to the recognition of a country typically falls somewhere between the ''declaratory'' and ''constitutive'' approaches.<ref>{{cite book |title=International law |url=https://archive.org/details/internationallaw00shaw_380 |url-access=limited |first1=Malcolm Nathan |last1=Shaw |year=2003 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page= |edition=5th |isbn=978-0-521-53183-2 }}</ref><ref name="Cohen 1961 p. 1127">{{cite journal | last=Cohen | first=Rosalyn | title=The Concept of Statehood in United Nations Practice | journal=University of Pennsylvania Law Review | volume=109 | issue=8 | date=1961 | pages=1127–1171 | doi=10.2307/3310588 | jstor=3310588 | s2cid=56273534 | url=https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol109/iss8/4 | archive-date=19 January 2024 | access-date=18 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240119201855/https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol109/iss8/4/ | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Kelsen 1941 pp. 605–617">{{cite journal | last=Kelsen | first=Hans | title=Recognition in International Law: Theoretical Observations | journal=The American Journal of International Law | publisher=American Society of International Law | volume=35 | issue=4 | year=1941 | issn=0002-9300 | jstor=2192561 | pages=605–617 | doi=10.2307/2192561 | s2cid=147309779 | url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2192561 | access-date=18 January 2024 | archive-date=18 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240118213745/https://www.jstor.org/stable/2192561 | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Lauterpacht 1944 pp. 385–458">{{cite journal | last=Lauterpacht | first=H. | title=Recognition of States in International Law | journal=The Yale Law Journal | publisher=The Yale Law Journal Company, Inc. | volume=53 | issue=3 | year=1944 | issn=0044-0094 | jstor=792830 | pages=385–458 | doi=10.2307/792830 | url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/792830 | access-date=18 January 2024 | archive-date=18 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240118213745/https://www.jstor.org/stable/792830 | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Anon. x863">{{cite web | |||

| Roman and Greek ideals of nationhood can be seen to have strongly influenced Western views on the subject, with the basis of many governmental systems being on authority or ideas borrowed from Rome or the Greek city-states. Notably, the European states of the Dark ages and Middle ages gained their authority from the Roman Catholic religion, and modern democracies are based in part on the example of Ancient Athens.{{fact}} | |||

| | title=Principles of the Recognition of States | |||

| | url=https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/13240/27_53YaleLJ385_1943_1944_.pdf?sequence=2 | |||

| | access-date=18 January 2024 | |||

| | archive-date=18 March 2024 | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240318013739/https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/13240/27_53YaleLJ385_1943_1944_.pdf?sequence=2 | |||

| | url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined territory, a government not under another, and the capacity to interact with other states.<ref name="Lowe 2015 pp. 1–18">{{cite book | last=Lowe | first=Vaughan | title=International Law: A Very Short Introduction | chapter=Nations under law | publisher=Oxford University PressOxford | date=2015-11-26 | isbn=978-0-19-923933-7 | doi=10.1093/actrade/9780199239337.003.0001 | page=1–18}}</ref> | |||

| [[File:Limited Recognition States.svg|thumb|upright=1.3| | |||

| === Middle ages === | |||

| {{legend|#C74355|UN member states that at least one other UN member state does not recognise}} | |||

| {{main|Middle ages}} | |||

| {{legend|#F8CD44|Non-UN member states recognised by at least one UN member state}} | |||

| ] in 700 CE]] | |||

| {{legend|#246788|Non-UN member states recognised only by other non-UN member states}} | |||

| ] entered the ],<ref>{{cite book |last=Benn |first=Charles D. |title=China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ile3jSveb4sC |format=HTML |accessdate=2008-12-17 |year=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0195176650 |pages=1}}</ref> this saw a change in government and an expansion in the country's borders as the many separate bureaucracies unified under one banner.<ref>{{cite book |last=Daniels |first=Patrica S |coauthors=Stephen G Hyslop, Douglas Brinkley, Esther Ferington, Lee Hassig, Dale-Marie Herring |editor=Toni Eugene |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=d5gPAQAACAAJ |format=HTML |title=Almanac of World History |year=2003 |publisher=National Geographic Society |isbn=0792250923 <!-- Need to figure out page no |pages= -->}}</ref> This evolved into the the ] when ] took control of China in 626.<ref>{{cite book |last=Benn |first=Charles D. |title=China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ile3jSveb4sC |format=HTML |accessdate=2008-12-17 |year=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0195176650 |pages=ix}}</ref> By now, the Chinese borders had expanded from eastern China, up north into the Tang Empire.<ref name="chinaatlas">{{cite book |last=Herrmann |first=Albert |title=Historical and Commercial Atlas of China |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5YnMGwAACAAJ |format=HTML |accessdate=2008-12-17 |year=1970 |publisher=Ch'eng-wen Publishing House}}</ref> The Tang Empire fell apart in 907 and split into ] with vague borders.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hucker |first=Charles O. |title=China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=wdqoHQRUhAYC |format=HTML |accessdate=2008-12-17 |year=1995 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=0804723532 |pages=147}}</ref> 53 years after the separation of the Tang Empire, China entered the ] under the rule of Chao K'uang, although the ] of this country expanded, they were never as large as those of the Tang dynasty and were constantly being redefined due to attacks from the neighboring ] people known is the ].<ref name="almanac">{{cite book |last=Daniels |first=Patrica S |coauthors=Stephen G Hyslop, Douglas Brinkley, Esther Ferington, Lee Hassig, Dale-Marie Herring |editor=Toni Eugene |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=d5gPAQAACAAJ |format=HTML |title=Almanac of World History |year=2003 |publisher=National Geographic Society |isbn=0792250923 <!-- Need to figure out page no |pages= -->}}</ref> | |||

| ]] | |||

| The ] outlined in the ] describes a state in ''Article 1'' as:<ref name="Anon. e743">{{cite web | |||

| In Western Europe, briefly mostly united into a single state under ] around 800CE, a few countries, including ], ], ] and ], had already effectively become ]s by 1,000CE, with the word kingdom largely co-terminus with a people mostly sharing a language and culture.{{Fact|date=January 2009}} | |||

| | title= Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States | |||

| | url= https://www.ilsa.org/Jessup/Jessup15/Montevideo%20Convention.pdf | |||

| | access-date= 18 January 2024 | |||

| | archive-date= 14 January 2024 | |||

| | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20240114065544/https://www.ilsa.org/Jessup/Jessup15/Montevideo%20Convention.pdf | |||

| | url-status= live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="Encyclopedia Britannica 1999 f033">{{cite web | title=States, Sovereignty, Treaties | website=Encyclopedia Britannica | date=26 July 1999 | url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-law/States-in-international-law | access-date=18 January 2024 | archive-date=30 April 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220430152154/https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-law/States-in-international-law | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| #Having a permanent population | |||

| #Having a defined territory | |||

| #Having a government | |||

| #Having the ability to enter into ] | |||

| The Montevideo Convention in ''Article 3'' implies that a sovereign state can still be a sovereign state even if no other countries recognise that it exists.<ref name="Anon. e743"/><ref name="Caspersen Stansfield 2012 p. 55">{{cite book | last1=Caspersen | first1=N. | last2=Stansfield | first2=G. | title=Unrecognized States in the International System | publisher=Taylor & Francis | series=Exeter Studies in Ethno Politics | year=2012 | isbn=978-1-136-84999-2 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ARtODc4lsdQC&pg=PA55 | access-date=18 January 2024 | page=55}}</ref> As a restatement of ], the Montevideo Convention merely codified existing legal norms and its principles,<ref name="D’Aspremont 2019 pp. 139–152">{{cite book | last=D’Aspremont | first=Jean | title=The Global Community Yearbook of International Law and Jurisprudence 2018 | chapter=Statehood and Recognition in International Law: A Post-Colonial Invention | publisher=Oxford University Press | date=2019-08-29 | isbn=978-0-19-007250-6 | doi=10.1093/oso/9780190072506.003.0005 | pages=139–152}}</ref> and therefore does not apply merely to the signatories of international organizations (such as the ]),<ref name="Seguin 2011 f032"/><ref name="Crawford 2007 p. "/><ref name="Encyclopedia Britannica 1999 f033"/> but to all subjects of international law as a whole.<ref>Harris, D.J. (ed) 2004 "Cases and Materials on International Law" 6th Ed. at p. 99. Sweet and Maxwell, London</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uGMxfj4oedEC&pg=PA77|title=International Law and Self-Determination: The Interplay of the Politics of Territorial Possession With Formulations of Post-Colonial National Identity|pages=77|year=2000|last=Castellino|first=Joshua|publisher=]|isbn=9041114092}}</ref> A similar opinion has been expressed by the ],<ref>{{cite book|last=Castellino|first=Joshua|title=International Law and Self-Determination: The Interplay of the Politics of Territorial Possession With Formulations of Post-Colonial National Identity|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uGMxfj4oedEC|year=2000|publisher=Martinus Nijhoff Publishers|isbn=978-90-411-1409-9|page=}}</ref> reiterated by the ], in the principal statement of its ],<ref>'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240118225642/https://openlearnlive-s3bucket.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/95/b1/95b1fc6c10918e7fa7a2acc8666197093b9f21be?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D%22Pellet%20A.,%20The%20Opinions%20of%20the%20Badinter%20Arbitration%20Committee.pdf%22&response-content-type=application/pdf&X-Amz-Content-Sha256=UNSIGNED-PAYLOAD&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA4GIOSMQ5JGMSLFXY/20240118/eu-west-2/s3/aws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20240118T225348Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=21552&X-Amz-Signature=86ad036490ea396a1fe3868843f2cf97b44bfd8666d9c0d3e7c03eadb6a503af |date=18 January 2024 }}'' (full title), named for its chair, ruled on the question of whether the Republics of Croatia, Macedonia, and Slovenia, who had formally requested recognition by the members of the European Union and by the EU itself, had met conditions specified by the Council of Ministers of the European Community on 16 December 1991. {{cite web |url=http://www.ejil.org/journal/Vol3/No1/art12.html |title=The Opinions of the Badinter Arbitration Committee: A Second Breath for the Self-Determination of Peoples |access-date=2012-05-10 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080517085252/http://www.ejil.org/journal/Vol3/No1/art12.html |archive-date=2008-05-17 }}</ref> and by Judge '']'', ].<ref name="Crawford 2007 p. ">{{cite book | last=Crawford | first=James R. | title=The Creation of States in International Law | publisher=Oxford University Press | date=2007-03-15 | isbn=978-0-19-922842-3 | doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199228423.003.0002 | pages=2–11}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ] a state is a legal entity of international law if, and only if, it is recognised as sovereign by at least one other country.<ref name="academic.oup.com s696">{{cite web | title=Statehood and Recognition | website=academic.oup.com | url=https://academic.oup.com/book/3288/chapter-abstract/144288950?redirectedFrom=fulltext | access-date=2024-01-21 | archive-date=26 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240126171048/https://academic.oup.com/book/3288/chapter-abstract/144288950?redirectedFrom=fulltext | url-status=live }}</ref> Because of this, new states could not immediately become part of the international community or be bound by international law, and recognised nations did not have to respect international law in their dealings with them.<ref name="ctos">{{cite book |title=Sourcebook on Public International Law |last=Hillier |first=Tim |year=1998 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-85941-050-9 |pages=201–2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Kr0sOuIx8q8C }}</ref> In 1912, ] said the following, regarding constitutive theory: | |||

| ] under Charlemagne around 800 CE, with modern borders in orange.]] | |||

| For most of the continent, the various peoples were emerging around ethnic, linguistic and geographical groupings. However, this was not reflected in the relevant political entities. In particular, ], ] and ], though recognised by other nations as areas where the ], ] and ] lived, for many centuries did not exist as single states matching their overall ethnic or linguistic makeup, and struggles to form and define their borders as states were a major cause of conflict in Europe until the 20th century. In the course of this process, some countries, such as ] under the ] and ] in the ], almost ceased to exist as states for periods. The ], in the Middle Ages as distinct a country as France, became permanently divided, into today's ] and the ]. ] was formed as a nation state by the dynastic union of small Christian kingdoms, augmented by the final campaigns of the ] against ], the now-vanished country of Islamic ].{{Fact|date=January 2009}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|International Law does not say that a State is not in existence as long as it is not recognised, but it takes no notice of it before its recognition. Through recognition only and exclusively a State becomes an International Person and a subject of International Law.<ref>{{cite book | first1 = Lassa | last1=Oppenheim | first2 = Ronald | last2 = Roxburgh | title = International Law: A Treatise | publisher = The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. | year = 2005 | isbn = 978-1-58477-609-3 | pages = 135 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=vxJ1Jwmyw0EC&pg=PA135}}</ref>}} | |||

| In 1299 CE,<ref>{{cite book |last=Tsouras |first=Peter |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Upxi59X8OB4C| format=HTML |title=Montezuma: Warlord of the Aztecs |year=2005 |publisher=Brassey's |isbn=1574888226 |pages=xv}}</ref> the ] empire arose in lower Mexico, this empire lasted over 500 years and at their prime, held over 5,000 square kilometers of land.<ref>{{cite book |last=Berdan |first=Frances F. |coauthors=Richard E. Blanton, Elizabeth H. Boone, Mary G. Hodge, Michael E. Smith, Emily Umberger |title=Aztec Imperial Strategies |isbn=0884022110 |year=1996 |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Dumbarton Oaks}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Barlow |first=R.H. |title=Extent of the Empire of the Culhua Mexica |year=1949 |publisher=Berkeley and Los Angeles Univ. of California}}</ref> | |||

| In 1976 the ] define state recognition as:<ref name="Talmon 1998 p. 186">{{cite book | last=Talmon | first=S. | title=Recognition of Governments in International Law: With Particular Reference to Governments in Exile | publisher=Clarendon Press | series=Oxford monographs in international law | year=1998 | isbn=978-0-19-826573-3 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=scc8EboiJX8C&pg=PA186 | access-date=2024-01-31 | page=186}}</ref> | |||

| ] in 1519 CE]] | |||

| {{Blockquote|..the recognition of an independent and sovereign state is an act of sovereignty pertaining each member of the international community, an act to be taken individually, and it is, therefore, up to member states and each OAU power whether to recognise or not the newly independent state.}} | |||

| 200 years after the Aztec and Toltec empires began, northern and central ] saw the rise of the ] empire. By the late 13th century, the Empire extended across Europe and Asia, briefly creating a state capable of ruling and administating immensely diverse cultures.<ref>{{cite book|last=Køppen|first=Adolph Ludvig|coauthors=Karl Spruner von Merz|title=The World in the Middle Ages: An Historical Geography, with Accounts of the Origin and Development, the Institutions and Literature, the Manners and Customs of Three Nations in Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, from the Close of the Fourth to the Middle of the Fifteenth Century|publisher=D. Appleton and company|date=1854|pages=210|accessdate=2009-01-11|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=4bujwAigzEgC}}</ref> In 1299, the ] entered the scene, these Turkish ] took control of Asia Minor along with much of central Europe over a period of 370 years, providing what may be considered a long-lasting Islamic counterweight to Christendom.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jacob|first=Samuel|title=History of the Ottoman Empire: Including a Survey of the Greek Empire and the Crusades|publisher=R. Griffin|date=1854|pages=456|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=iBwpAAAAYAAJ|accessdate=2009-01-11}}</ref> | |||

| ]{{refn|group=note|Each territory in the ] is labeled '''UM-''' followed by the first letter of its name and another unique letter if needed.}} or with numbers.{{refn|group=note|The following territories do not have ] codes:<br>'''1''': ]<br>'''2''': ]<br>'''3''': ]}} Colored areas without labels are integral parts of their respective countries. ] is shown as a ] instead of ].]] | |||

| Exploiting opportunities left open by the Mongolian advance and recession as well as the spread of Islam. Russia took control of their homeland around 1613, after many years being domianted by the Tartars. After gaining independence, The Russian princes began to expand their borders under the leadership of many ].<ref name="almanac"/> Notably, ] seized the vast western part of ] from the ], expanding Russia's size massively. Throughout the following centuries, Russia expanded rapidly, coming close to its modern size.<ref>{{cite book|last=Thomson|first=Gladys Scott|title=Catherine the Great and the Expansion of Russia|publisher=Read Books|date=20008|isbn=1443728950|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kpcAMf-7W9kC|accessdate=2008-01-14}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Will start this soon | |||

| Some countries, such as ], ] and ] have disputed sovereignty and/or limited recognition among some countries.<ref name="Kyris 2022 pp. 287–311">{{cite journal | last=Kyris | first=George | title=State recognition and dynamic sovereignty | journal=European Journal of International Relations | volume=28 | issue=2 | date=2022 | issn=1354-0661 | doi=10.1177/13540661221077441 | pages=287–311}}</ref><ref name="Allcock Lampe Young 1998 q703">{{cite web | last1=Allcock | first1=John B. | last2=Lampe | first2=John R. | last3=Young | first3=Antonia | title=History, Map, Flag, Population, Languages, & Capital | website=Encyclopedia Britannica | date=1998-07-20 | url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Kosovo | access-date=2024-01-29 | archive-date=19 June 2015 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150619045343/https://www.britannica.com/place/Kosovo | url-status=live }}</ref> Some sovereign states are unions of separate polities, each of which may also be considered a country in its own right, called constituent countries. The ] consists of ], the ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |date=15 January 2020 |title=Greenland and the Faroe Islands |url=https://www.eu.dk/da/english/greenland-and-the-faroe-islands |access-date=25 January 2021 |publisher=The Danish Parliament – EU Information Centre |archive-date=9 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210209112007/https://www.eu.dk/da/english/greenland-and-the-faroe-islands |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] consists of the ], ], ], and ].<ref name="den Heijer van der Wilt 2022 p. 362">{{cite book | last1=den Heijer | first1=M. | last2=van der Wilt | first2=H. | title=Netherlands Yearbook of International Law 2020: Global Solidarity and Common but Differentiated Responsibilities | publisher=T.M.C. Asser Press | year=2022 | isbn=978-94-6265-527-0 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FoCFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA362 | access-date=21 January 2024 | page=362}}</ref> The ] consists of ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Barnett 2023 p. 93">{{cite book | last=Barnett | first=H. | title=Constitutional and Administrative Law | publisher=Taylor & Francis | year=2023 | isbn=978-1-000-91065-0 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4PTEEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT93 | access-date=21 January 2024 | page=93}}</ref> | |||

| === Early modern era === | |||

| {{main|Early modern era}} | |||

| Dependent territories are the territories of a sovereign state that are outside of its proper territory. These include the ], the ], the ] and ], the ], the ], the ], the autonomous regions of the Danish Realm, ], ], and the ]. Some dependent territories are treated as a separate "]" in international trade,<ref>{{Cite web |date=23 November 2021 |title=Canadian Importers Database – Home |url=http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cid-dic.nsf/eng/Home |access-date=17 April 2022 |archive-date=23 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220423232611/https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cid-dic.nsf/eng/home |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=20 June 2017 |title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, General Preferential Tariff and Least Developed Country Tariff Rules of Origin Regulations |url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2013-165/FullText.html |access-date=17 April 2022 |archive-date=17 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220417083011/https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2013-165/FullText.html |url-status=live }}</ref> such as ],<ref>{{cite web |title=Made In The British Crown Colony |url=http://thuytiencrampton.com/2010/07/07/made-in-the-british-crown-colony/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407075644/http://thuytiencrampton.com/2010/07/07/made-in-the-british-crown-colony/ |archive-date=2014-04-07 |work=Thuy-Tien Crampton}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Matchbox label, made in Hong Kong |url=http://www.delcampe.net/page/item/id,41342017,var,MATCHBOX-LABEL-MADE-IN-HONG-KONG,language,E.html#.Uzrl3vmSwZg |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20140401162502/http://www.delcampe.net/page/item/id,41342017,var,MATCHBOX-LABEL-MADE-IN-HONG-KONG,language,E.html%23.UzroWH3LfK5#.Uzrl3vmSwZg |archive-date=1 April 2014 |work=delcampe.net}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Carrhart Made In Hong Kong? |url=http://www.contractortalk.com/f40/carrhart-made-hong-kong-27324/ |work=ContractorTalk |access-date=28 May 2014 |archive-date=7 April 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140407174000/http://www.contractortalk.com/f40/carrhart-made-hong-kong-27324/ |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.trademarkelite.com/europe/trademark/trademark-detail/017910465/PRODUCT-OF-GREENLAND-INLAND-ICE |title=Product of Greenland Inland Ice Trademark of Inland Ice Denmark ApS. Application Number: 017910465 :: Trademark Elite Trademarks |access-date=14 September 2022 |archive-date=11 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230111202441/https://www.trademarkelite.com/europe/trademark/trademark-detail/017910465/PRODUCT-OF-GREENLAND-INLAND-ICE |url-status=live }}</ref> and ].<ref name="International Trade Administration 2019 r527">{{cite web | title=Hong Kong & Macau | website=International Trade Administration | date=2019-12-20 | url=https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/hong-kong-macau-market-overview | access-date=2024-01-31 | archive-date=7 September 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230907075725/https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/hong-kong-macau-market-overview | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| --> | |||

| === Identification === | |||

| {{Further|National symbol}} | |||

| Symbols of a country may incorporate ], ] or ] symbols of any nation that the country includes. Many categories of symbols can be seen in flags, coats of arms, or seals.<ref name="CIA x692">{{cite web | title=National symbol(s) | website=CIA | url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/national-symbols/ | access-date=2024-01-24 | archive-date=8 November 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161108112336/https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2230.html | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Name === | |||

| {{see also|List of country-name etymologies}} | |||

| ]) and TK (])]] | |||

| Most countries have a long name and a short name.<ref name="United States Department of State 2024 e471">{{cite web | title=United States Department of State | website=United States Department of State | date=17 Jan 2024 | url=https://www.state.gov/independent-states-in-the-world/ | access-date=29 Jan 2024 | archive-date=3 April 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403144919/https://www.state.gov/s/inr/rls/4250.htm | url-status=live }}</ref> The long name is typically used in formal contexts and often describes the country's form of government. The short name is the country's common name by which it is typically identified.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-5000500.htm|title=Publications Office – Interinstitutional Style Guide – Annex A5 – List of countries, territories and currencies|website=publications.europa.eu|access-date=5 September 2020|archive-date=28 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190528204637/http://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-5000500.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url = https://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/geonames/| title = UNGEGN World Geographical Names| access-date = 5 September 2020| archive-date = 28 July 2011| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110728144249/http://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/geonames/| url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/iso3list/en/|title=FAO Country Profiles|website=Food and Agriculture Organization|access-date=5 September 2020|archive-date=2 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210202012235/http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/iso3list/en/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url = https://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-370100.htm| title = Countries: Designations and abbreviations to use| access-date = 5 September 2020| archive-date = 4 January 2021| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210104160434/https://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-370100.htm| url-status = live}}</ref> The ] maintains a ] as part of ] to designate each country with a two-letter ].<ref name=":02">{{Cite web |title=ISO 3166 – Country Codes |url=https://www.iso.org/iso-3166-country-codes.html |access-date=2022-07-21 |website=ISO |language=en |archive-date=8 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170308003724/https://www.iso.org/iso-3166-country-codes.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The name of a country can hold cultural and diplomatic significance. ] changed its name to ] to reflect the end of French colonization, and the name of ] was ] for years due to a conflict with the similarly named ] region in ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Savage |first=Jonathan |date=2018-01-21 |title=Why do names matter so much? |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-42736495 |access-date=2022-07-21 |archive-date=21 July 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220721043621/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-42736495 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ISO 3166-1 standard currently comprises 249 countries, 193 of which are sovereign states that are members of the United Nations.<ref name="Statistics Canada 2018 b784">{{cite web | title=Standard Classification of Countries and Areas of Interest (SCCAI) 2017 | website=Statistics Canada | date=12 Mar 2018 | url=https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects/standard/sccai/2017/introduction | access-date=29 Jan 2024 | archive-date=29 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240129073744/https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects/standard/sccai/2017/introduction | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Flags === | |||

| {{main|National flag}} | |||

| {{See also|List of national flags of sovereign states}} | |||

| ] (flown 1867–1890), upper left; the ], upper, right; the ], lower left; and the ] with inset ], lower right. Various other flags flown by ships are shown. The ] is labelled "Cuban ]". The ] on the ] was drawn mistakenly as a ].]] | |||

| Originally, flags representing a country would generally be the personal flag of its rulers; however, over time, the practice of using personal banners as flags of places was abandoned in favor of flags that had some significance to the nation, often its patron saint. Early examples of these were the ] such as ] which could be said to have a national flag as early as the 12th century.{{sfn|Barraclough|1971|pp=7–8}} However, these were still mostly used in the context of marine identification.<ref name="Devereux 1994 p. ">{{cite book | last=Devereux | first=E. | title=Flags: The New Compact Study Guide and Identifier | publisher=Chartwell Books | series=Eyewitness books | year=1994 | isbn=978-0-7858-0049-1| page=18}}</ref> | |||

| Although some flags date back earlier, widespread use of flags outside of military or naval context begins only with the rise of the idea of the ] at the end of the 18th century and particularly are a product of the ]. Revolutions such as those in ] and ] called for people to begin thinking of themselves as ] as opposed to ] under a king, and thus necessitated flags that represented the collective citizenry, not just the power and right of a ruling family.{{sfn|Nadler|2016}}{{sfn|Inglefield|Mould|1979|p=48}} With ] becoming common across Europe in the 19th century, national flags came to represent most of the states of Europe.{{sfn|Nadler|2016}} Flags also began fostering a sense of unity between different peoples, such as the ] representing a union between ] and ], or began to represent unity between nations in a perceived shared struggle, for example, the ] or later ].{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=31}} | |||

| As Europeans ] significant portions of the world, they exported ideas of nationhood and national symbols, including flags, with the adoption of a flag becoming seen as integral to the ] process.{{sfn|Virmani|1999|p=169}} Political change, social reform, and revolutions combined with a growing sense of nationhood among ordinary people in the 19th and 20th centuries led to the birth of new nations and flags around the globe.{{sfn|Inglefield|Mould|1979|p=50}} With so many flags being created, interest in these designs began to develop and the study of flags, ], at both professional and amateur levels, emerged. After World War II, Western vexillology went through a phase of rapid development, with many research facilities and publications being established.{{sfn|Xing|2013|p=2}} | |||

| === National anthems === | |||

| {{main| National anthem }} | |||

| {{seealso|List of national anthems}} | |||

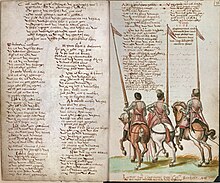

| ], MS 15662, fol. 37v-38r)<ref>M. de Bruin, "Het Wilhelmus tijdens de Republiek", in: L.P. Grijp (ed.), ''Nationale hymnen. Het Wilhelmus en zijn buren. Volkskundig bulletin 24'' (1998), p. 16-42, 199–200; esp. p. 28 n. 65.</ref>]] | |||

| A national anthem is a ] ] symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation.<ref>{{Cite web |title=National anthem – The World Factbook |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/national-anthem/ |access-date=2021-05-27 |website=Central Intelligence Agency |archive-date=5 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220805175145/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/national-anthem/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Though the custom of an officially adopted national anthem became popular only in the 19th century, some national anthems predate this period, often existing as patriotic songs long before designation as national anthem.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} Several countries remain without an official national anthem. In these cases, there are established '']'' anthems played at sporting events or diplomatic receptions. These include the United Kingdom ("]") and Sweden ({{lang|sv|]}}). Some sovereign states that are made up of multiple countries or constituencies have associated musical compositions for each of them (such as with the ], ], and the ]). These are sometimes referred to as national anthems even though they are not sovereign states (for example, "]" is used for Wales, part of the United Kingdom).<ref name="Harrison 2022 x303">{{cite web | last=Harrison | first=Ellie | title=The history of the Welsh national anthem that's gripped the world | website=The Independent | date=29 November 2022 | url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/wales-world-cup-anthem-lyrics-translation-b2235003.html | access-date=29 January 2024 | archive-date=29 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240129160133/https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/wales-world-cup-anthem-lyrics-translation-b2235003.html | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Other symbols === | |||

| * ] or ]s | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]s | |||

| * ] | |||

| == Patriotism == | |||

| {{main|Patriotism}} | |||

| {{See also|Cultural nationalism}} | |||

| A positive emotional connection to a country a person belongs to is called ]. Patriotism is a sense of love for, devotion to, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, and language relating to one's homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political, or historical aspects. It encompasses a set of concepts closely related to ], mostly ] and sometimes ].<ref name="books.google.com">{{cite book |author=Harvey Chisick |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5N-wqTXwiU0C&pg=PA313 |title=Historical Dictionary of the Enlightenment |date=2005 | publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0810865488 |access-date=2013-11-03 |archive-date=25 September 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140925183305/http://books.google.com/books?id=5N-wqTXwiU0C&pg=PA313 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Nationalism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nationalism/ |access-date=2013-11-03 |publisher=Plato.stanford.edu |archive-date=22 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180922061455/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nationalism/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| ] per capita of 213 "countries" (2020) (] – ]) | |||

| <br />{{hlist|{{legend inline|#4b0049|>50,000}}|{{legend inline|#680063|35,000–50,000}}|{{legend inline|#814991|20,000–35,000}}|{{legend inline|#8c6bb1|10,000–20,000}}|{{legend inline|#8c96c6|5,000–10,000}}|{{legend inline|#9ebcda|2,000–5,000}}|{{legend inline|#bfd3e6|<2,000}}|{{legend inline|#999999|Data unavailable}}}}]] | |||

| Several organizations seek to identify trends to produce economy country classifications. Countries are often distinguished as ] or ].<ref name="Paprotny 2020 pp. 193–225">{{cite journal | last=Paprotny | first=Dominik | title=Convergence Between Developed and Developing Countries: A Centennial Perspective | journal=Social Indicators Research | publisher=Springer Science and Business Media LLC | volume=153 | issue=1 | date=14 Sep 2020 | issn=0303-8300 | doi=10.1007/s11205-020-02488-4 | pages=193–225| pmid=32952263 | pmc=7487265 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] annually produces the ''World Economic Situation and Prospects Report'' classifies states as developed countries, economies in transition, or developing countries. The report classifies country development based on per capita ] (GNI).<ref name="Nations 2020 k704">{{cite web | last=Nations | first=United | title=What We Do | publisher=United Nations | date=20 Sep 2020 | url=https://www.un.org/en/desa/what-we-do | access-date=29 Jan 2024 | archive-date=18 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240118062114/https://www.un.org/en/desa/what-we-do/ | url-status=live }}</ref> The UN identifies subgroups within broad categories based on geographical location or ad hoc criteria. The UN outlines the geographical regions for developing economies like Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Western Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The 2019 report recognizes only developed countries in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Pacific. The majority of economies in transition and developing countries are found in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean.<ref name="UNCTAD 2023 e635">{{cite web | title=UN list of least developed countries | website=UNCTAD | date=1 Dec 2023 | url=https://unctad.org/topic/least-developed-countries/list | access-date=29 Jan 2024 | archive-date=1 August 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230801215744/https://unctad.org/topic/least-developed-countries/list | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The ] also classifies countries based on GNI per capita. The ''World Bank Atlas method'' classifies countries as low-income economies, lower-middle-income economies, upper-middle-income economies, or high-income economies. For the 2020 fiscal year, the World Bank defines low-income economies as countries with a GNI per capita of $1,025 or less in 2018; lower-middle-income economies as countries with a GNI per capita between $1,026 and $3,995; upper-middle-income economies as countries with a GNI per capita between $3,996 and $12,375; high-income economies as countries with a GNI per capita of $12,376 or more..<ref name="World Bank Data Help Desk 2022 x420"/> | |||

| It also identifies regional trends. The World Bank defines its regions as East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, the World Bank distinguishes countries based on its operational policies. The three categories include ] (IDA) countries, ] (IBRD) countries, and Blend countries.<ref name="World Bank Data Help Desk 2022 x420">{{cite web | title=How does the World Bank classify countries? | website=World Bank Data | date=1 Jul 2022 | url=https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries | access-date=29 Jan 2024 | archive-date=22 May 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200522092916/https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378834-how-does-the-world-bank-classify-countries | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal|Countries|Politics|World}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist|group=note}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{reflist}} | ||

| <!-- | <!-- | ||

| *Anderson, Benedict; 'Imagined Communities: Reflections On the origin and Spread of Nationalism'; London, Verso; 1991 | * Anderson, Benedict; 'Imagined Communities: Reflections On the origin and Spread of Nationalism'; London, Verso; 1991 | ||

| *Viotti, Paul R. and Kauppi, Mark V.; 'International Relations and World Politics |

* Viotti, Paul R. and Kauppi, Mark V.; 'International Relations and World Politics – Security, Economy, Identity; Second Edition; New Jersey, Prentice-Hall; 2001 | ||

| --> | --> | ||

| ===Works cited=== | |||

| {{refbegin|30em}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Barraclough |first1=E.M.C. |title=Flags of the World |date=1971 |publisher=William Cloves & Sons Ltd |location=Great Britain |isbn=0723213380}} | |||

| * {{cite conference |last=Bartlett |first=Ralph G. C. |date=2011 |url=https://fiav.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/icv24-04bartlett.pdf |title=Unity in Flags |publisher=International Federation of Vexillological Associations |conference=24th International Congress of Vexillology |location=Alexandria, Virginia |access-date=12 December 2022 |archive-date=24 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221224155654/https://fiav.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/icv24-04bartlett.pdf |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Inglefield |first1=Eric |last2=Mould |first2=Tony |title=Flags |date=1979 |publisher=Ward Lock |isbn=978-0706356526}} | |||

| * {{cite news |last1=Nadler |first1=Ben |title=Where Do Flags Come From? |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/06/happy-flag-day/486866/ |access-date=24 November 2021 |work=] |date=14 June 2016 |archive-date=24 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211124011425/https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/06/happy-flag-day/486866/ |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Virmani |first1=Arundhati |author1-link=Arundhati Virmani |title=National Symbols under Colonial Domination: The Nationalization of the Indian Flag, March-August 1923 |journal=Past & Present |date=August 1999 |issue=164 |pages=169–197 |jstor=651278 |publisher=Oxford University Press|doi=10.1093/past/164.1.169 }} | |||

| * {{cite conference |last=Xing |first=Fei |date=2013 |url=https://fiav.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ICV2512-Xing-Fei-The-Study-of-Vexillology-in-China.pdf |title=The Study of Vexillology in China |publisher=International Federation of Vexillological Associations |conference=25th International Congress of Vexillology |location=Rotterdam |access-date=12 December 2022 |archive-date=16 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220616162946/https://fiav.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ICV2512-Xing-Fei-The-Study-of-Vexillology-in-China.pdf |url-status=live }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * ''The Economist'' | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | * | ||

| * from the ] |

* from the ] | ||

| * and from GovPubs at UCB Libraries | |||

| * from ] | |||

| * from the ] | * | ||

| * and from GovPubs at UCB Libraries | |||

| {{sister bar|auto=1|d=y}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Lists of countries and territories by continent}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{States with limited recognition}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:41, 3 January 2025

Distinct territorial body or political entity Not to be confused with County. For countryside, see Rural area. For other uses, see Country (disambiguation).

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. When referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a sovereign state, states with limited recognition, constituent country, or a dependent territory. Most sovereign states, but not all countries, are members of the United Nations. There is no universal agreement on the number of "countries" in the world since several states have disputed sovereignty status, limited recognition and a number of non-sovereign entities are commonly considered countries.

The definition and usage of the word "country" are flexible and have changed over time. The Economist wrote in 2010 that "any attempt to find a clear definition of a country soon runs into a thicket of exceptions and anomalies."

Areas much smaller than a political entity may be referred to as a "country", such as the West Country in England, "big sky country" (used in various contexts of the American West), "coal country" (used to describe coal-mining regions), or simply "the country" (used to describe a rural area). The term "country" is also used as a qualifier descriptively, such as country music or country living.

Etymology

The word country comes from Old French contrée, which derives from Vulgar Latin (terra) contrata ("(land) lying opposite"; "(land) spread before"), derived from contra ("against, opposite"). It most likely entered the English language after the Franco-Norman invasion during the 11th century.

Definition of a country

In English the word has increasingly become associated with political divisions, so that one sense, associated with the indefinite article – "a country" – is now frequently applied as a synonym for a state or a former sovereign state. It may also be used as a synonym for "nation". Taking as examples Canada, Sri Lanka, and Yugoslavia, cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote in 1997 that "it is clear that the relationships between 'country' and 'nation' are so different from one to the next as to be impossible to fold into a dichotomous opposition as they are into a promiscuous fusion."

Areas much smaller than a political state may be referred to as countries, such as the West Country in England, "big sky country" (used in various contexts of the American West), "coal country" (used to describe coal-mining regions in several sovereign states) and many other terms. The word "country" is also used for the sense of native sovereign territory, such as the widespread use of Indian country in the United States. The term "country" in English may also be wielded to describe rural areas, or used in the form "countryside." Raymond Williams, a Welsh scholar, wrote in 1975:

'Country' and 'city' are very powerful words, and this is not surprising when we remember how much they seem to stand for in the experience of human communities. In English, 'country' is both a nation and a part of a 'land'; 'the country' can be the whole society or its rural area. In the long history of human settlements, this connection between the land from which directly or indirectly we all get our living and the achievements of human society has been deeply known.

The unclear definition of "country" in modern English was further commented upon by philosopher Simon Keller:

Often, a country is presumed to be identical with a collection of citizens. Sometimes, people say that a country is a project, or an idea, or an ideal. Occasionally, philosophers entertain more metaphysically ambitious pictures, suggesting that a country is an organic entity with its own independent life and character, or that a country is an autonomous agent, just like you or me. Such claims are rarely explained or defended, however, and it is not clear how they should be assessed. We attribute so many different kinds of properties to countries, speaking as though a country can feature wheat fields waving or be girt by sea, can have a founding date and be democratic and free, can be English speaking, culturally diverse, war torn or Islamic.

— New Waves In Political Philosophy, "Making Nonsense of Loyalty to Country", page 96

Melissa Lucashenko, an Aboriginal Australian writer, expressed the difficulty of defining "country" in a 2005 essay, "Unsettlement":

...What is this thing country? What does country mean? ... I spoke with others who said country meant Home, but who added the caveat that Home resided in people rather than places – a kind of portable Country... I tried to tease out some ways in which non-Indigenous people have understood country. I made categories: Country as Economy. Country as Geography. Country as Society. Country as Myth. Country as History. For all that I walked, slept, breathed and dreamed Country, the language still would not come.

Statehood

Main article: Sovereign state See also: List of sovereign states, List of sovereign states and dependent territories by continent, and List of states with limited recognitionWhen referring to a specific polity, the term "country" may refer to a sovereign state, states with limited recognition, constituent country, or a dependent territory. A sovereign state is a political entity that has supreme legitimate authority over a part of the world. There is no universal agreement on the number of "countries" in the world since several states have disputed sovereignty status, and a number of non-sovereign entities are commonly called countries. No definition is binding on all the members of the community of nations on the criteria for statehood. State practice relating to the recognition of a country typically falls somewhere between the declaratory and constitutive approaches. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined territory, a government not under another, and the capacity to interact with other states.

The declarative theory outlined in the 1933 Montevideo Convention describes a state in Article 1 as:

- Having a permanent population

- Having a defined territory

- Having a government

- Having the ability to enter into relations with other states

The Montevideo Convention in Article 3 implies that a sovereign state can still be a sovereign state even if no other countries recognise that it exists. As a restatement of customary international law, the Montevideo Convention merely codified existing legal norms and its principles, and therefore does not apply merely to the signatories of international organizations (such as the United Nations), but to all subjects of international law as a whole. A similar opinion has been expressed by the European Economic Community, reiterated by the European Union, in the principal statement of its Badinter Committee, and by Judge Challis Professor, James Crawford.

According to the constitutive theory a state is a legal entity of international law if, and only if, it is recognised as sovereign by at least one other country. Because of this, new states could not immediately become part of the international community or be bound by international law, and recognised nations did not have to respect international law in their dealings with them. In 1912, L. F. L. Oppenheim said the following, regarding constitutive theory:

International Law does not say that a State is not in existence as long as it is not recognised, but it takes no notice of it before its recognition. Through recognition only and exclusively a State becomes an International Person and a subject of International Law.

In 1976 the Organisation of African Unity define state recognition as:

..the recognition of an independent and sovereign state is an act of sovereignty pertaining each member of the international community, an act to be taken individually, and it is, therefore, up to member states and each OAU power whether to recognise or not the newly independent state.

Some countries, such as Taiwan, Sahrawi Republic and Kosovo have disputed sovereignty and/or limited recognition among some countries. Some sovereign states are unions of separate polities, each of which may also be considered a country in its own right, called constituent countries. The Danish Realm consists of Denmark proper, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. The Kingdom of the Netherlands consists of the Netherlands proper, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten. The United Kingdom consists of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Dependent territories are the territories of a sovereign state that are outside of its proper territory. These include the overseas territories of New Zealand, the dependencies of Norway, the British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, the territories of the United States, the external territories of Australia, the special administrative regions of China, the autonomous regions of the Danish Realm, Åland, Overseas France, and the Caribbean Netherlands. Some dependent territories are treated as a separate "country of origin" in international trade, such as Hong Kong, Greenland, and Macau.

Identification

Further information: National symbolSymbols of a country may incorporate cultural, religious or political symbols of any nation that the country includes. Many categories of symbols can be seen in flags, coats of arms, or seals.

Name

See also: List of country-name etymologies

Most countries have a long name and a short name. The long name is typically used in formal contexts and often describes the country's form of government. The short name is the country's common name by which it is typically identified. The International Organization for Standardization maintains a list of country codes as part of ISO 3166 to designate each country with a two-letter country code. The name of a country can hold cultural and diplomatic significance. Upper Volta changed its name to Burkina Faso to reflect the end of French colonization, and the name of North Macedonia was disputed for years due to a conflict with the similarly named Macedonia region in Greece. The ISO 3166-1 standard currently comprises 249 countries, 193 of which are sovereign states that are members of the United Nations.

Flags

Main article: National flag See also: List of national flags of sovereign states

Originally, flags representing a country would generally be the personal flag of its rulers; however, over time, the practice of using personal banners as flags of places was abandoned in favor of flags that had some significance to the nation, often its patron saint. Early examples of these were the maritime republics such as Genoa which could be said to have a national flag as early as the 12th century. However, these were still mostly used in the context of marine identification.