| Revision as of 20:50, 3 July 2008 editLeadwind (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers7,963 editsm →Hymn to the Word: typo← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:30, 19 January 2025 edit undo66.215.184.32 (talk) Fixed issue with alphabetical order. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Book of the New Testament}} | |||

| {{otheruse|The Gospel of John (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{About|the book in the New Testament|the films|The Gospel of John (2003 film)|and|The Gospel of John (2014 film)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|John (book)|other uses|John (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Book of John|other uses|Book of John (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Johannine epistles}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

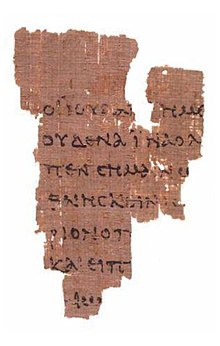

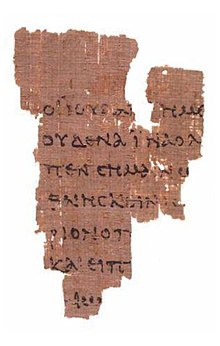

| ] (''recto''; {{Circa|AD 150}}).]] | |||

| {{Books of the New Testament}} | {{Books of the New Testament}} | ||

| {{John}} | |||

| The '''Gospel of John'''{{Efn|The book is sometimes called the '''Gospel according to John''', or simply '''John'''<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HiPouAEACAAJ |title=ESV Pew Bible |publisher=Crossway |year=2018 |isbn=978-1-4335-6343-0 |location=Wheaton, IL |page=886 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210603093159/https://www.google.com/books/edition/ESV_Pew_Bible_Black/HiPouAEACAAJ |archive-date=June 3, 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> (which is also its most common form of abbreviation).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Bible Book Abbreviations |url=https://www.logos.com/bible-book-abbreviations |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220421100743/https://www.logos.com/bible-book-abbreviations |archive-date=April 21, 2022 |access-date=April 21, 2022 |website=Logos Bible Software}}</ref>}} ({{langx|grc|Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην|translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn}}) is the fourth of the ]'s four ]. It contains a highly schematic account of the ], with seven "]" culminating in the ] (foreshadowing the ]) and seven "]" discourses (concerned with issues of the ] at the time of composition){{sfn|Lindars|1990|p=53}} culminating in ]'s proclamation of the risen Jesus as "my Lord and my God".{{sfn|Witherington|2004|p=83}} The gospel's concluding verses set out its purpose, "that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."{{sfn|Edwards|2015|p=171}}{{sfn|Burkett|2002|p=215}} | |||

| The '''Gospel of John''' (literally, ''According to John''; ], Κατὰ Ἰωάννην, ''Kata Iōannēn'') is the fourth ] in the ] of the ], traditionally ascribed to ]. Like the three ], it contains an account of some of the actions and sayings of ], but differs from them in ] and theological emphases. The Gospel appears to have been written with an evangelistic purpose, primarily for Greek-speaking Jews who were not believers,<ref>Colin G. Kruse, ''The Gospel According to John: An Introduction and Commentary'', Eerdmans (2004), page 21. ISBN 0802827713</ref>, or to strengthen the faith of Christians.<ref name="ODCC self">"Gospel of John." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005</ref> A second purpose was to counter criticisms or unorthodox beliefs of Jews, ]'s followers, and those who believed Jesus was only spirit and not flesh.<ref name ="Harris">], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| John reached its final form around AD 90–110,{{sfn|Lincoln|2005|p=18}} although it contains signs of origins dating back to AD 70 and possibly even earlier.{{sfn|Hendricks|2007|p=147}} Like the three other gospels, it is anonymous, although it identifies an unnamed "]" as the source of its traditions.{{sfn|Reddish|2011|pp=13}}{{sfn|Burkett|2002|p=214}} It most likely arose within a "]",{{sfn|Reddish|2011|p=41}}{{sfn|Bynum|2012|p=15}} and – as it is closely related in style and content to the three ] – most scholars treat the four books, along with the ], as a single corpus of ], albeit not by the same author.{{sfn|Harris|2006|p=479}} | |||

| Of the four gospels, John presents the highest ], describing him as the ] who is the ] (a Greek term for "existed from the beginning" or "the ultimate source of all things"), teaching at length about his identity as savior, and possibly declaring him to be God.<ref>A detailed technical discussion can be found in ], "Does the New Testament call Jesus God?" ''Theological Studies'' 26 (1965): 545–73</ref> | |||

| ==Authorship== | |||

| Compared to the ], John focuses on Jesus' mission to bring the Logos ("Word", "Wisdom", "Reason" or "Rationality") to his ]. Only in John does Jesus talk at length about himself, including a substantial amount of material Jesus shared with the disciples only. Here Jesus' public ministry consists largely of miracles not found in the Synoptics, including raising Lazarus from the dead. In John, Jesus, not his message, has become the object of veneration.<ref name ="Harris">], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> Certain elements of the synoptics (such as ], ], and possibly the ]) are not found in John. | |||

| {{Main|Authorship of the Johannine works#Gospel of John}} | |||

| ===Composition=== | |||

| Since "]" of the 19th century, historians have questioned the gospel of John as a reliable source of information about the ].<ref>, in Catholic Encyclopedia 1910</ref><ref>"In particular, the fourth Gospel, which does not emanate or profess to emanate from the apostle John, cannot be taken as an historical authority in the ordinary meaning of the word. The author of it acted with sovereign freedom, transposed events and put them in a strange light, drew up the discourses himself, and illustrated 22 great thoughts by imaginary situations. Although, his work is not altogether devoid of a real, if scarcely recognisable, traditional element, it can hardly make any claim to be considered an authority for Jesus’ history; only little of what he says can be accepted, and that little with caution. On the other hand, it is an authority of the first rank for answering the question, What vivid views of Jesus’ person, what kind of light and warmth, did the Gospel disengage?" ] </ref><ref>Harris says John's biography is "highly problematical to scholars..." p. 268. ], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> Most scholars regard the work as anonymous,<ref>]. ''Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction'', 2nd ed. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. page 302.</ref><ref>Delbert Burkett, ''An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity'', Cambridge University Press, (2002), page 215.</ref><ref>F. F. Bruce, ''The Gospel of John'', Eerdmans (1994), page 1.</ref> and date it to ''c'' 90–100.<ref name ="Harris"/> | |||

| The Gospel of John, like all the gospels, is anonymous.{{sfn|O'Day|1998|p=381}} John 21:22<ref>{{bibleverse|John|21:22}}</ref> references a ] and John 21:24–25<ref>{{bibleverse|John|21:24–25}}</ref> says: "This is the disciple who is testifying to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true".{{sfn|Reddish|2011|p=41}} Early Christian tradition, first found in ] ({{circa|130|202}} AD), identified this disciple with ], but most scholars have abandoned this hypothesis or hold it only tenuously;{{sfn|Lindars|Edwards|Court|2000|p=41}} there are multiple reasons for this conclusion, including, for example, the fact that the gospel is written in good Greek and displays sophisticated theology, and is therefore unlikely to have been the work of a simple fisherman.{{sfn|Kelly|2012|p=115}} Rather, these verses imply that the core of the gospel relies on the testimony (perhaps written) of the "disciple who is testifying", as collected, preserved, and reshaped by a community of followers (the "we" of the passage), and that a single follower (the "I") rearranged this material and perhaps added the final chapter and other passages to produce the final gospel.{{sfn|Reddish|2011|p=41}} Most scholars estimate the final form of the text to be around AD 90–110.{{sfn|Lincoln|2005|p=18}} Given its complex history there may have been more than one place of composition, and while the author was familiar with Jewish customs and traditions, their frequent clarification of these implies that they wrote for a mixed Jewish/Gentile or Gentile audience outside ]. | |||

| The author may have drawn on a "signs source" (a collection of miracles) for chapters 1–12, a "passion source" for the story of Jesus's arrest and crucifixion, and a "sayings source" for the discourses, but these hypotheses are much debated,{{sfn|Reddish|2011|pp=187–188}} and recent scholarship has tended to turn against positing hypothetical sources for John.<ref>{{cite book |last= Keith |first= Chris |year= 2020 |title= The Gospel as Manuscript: An Early History of the Jesus Tradition as Material Artifact |publisher= Oxford University Press |page= 142 |isbn= 978-0199384372}}</ref> The author seems to have known some version of Mark and Luke, as John shares with them some vocabulary and clusters of incidents arranged in the same order,{{sfn|Lincoln|2005|pp=29–30}}{{sfn|Fredriksen|2008|p=unpaginated}} but key terms from those gospels are absent or nearly so, implying that if the author did know them they felt free to write independently.{{sfn|Fredriksen|2008|p=unpaginated}} The Hebrew scriptures were an important source,{{sfn|Valantasis|Bleyle|Haugh|2009|p=14}} with 14 direct quotations (versus 27 in Mark, 54 in Matthew, 24 in Luke), and their influence is vastly increased when allusions and echoes are included,{{sfn|Yu Chui Siang Lau|2010|p=159}} but the majority of John's direct quotations do not agree exactly with any known version of the Jewish scriptures.{{sfn|Menken|1996|pp=11–13}} Recent arguments by ] and others that John preserves eyewitness testimony have not won general acceptance.{{sfn|Eve|2016|p=135}}{{sfn|Porter|Fay|2018|p=41}} | |||

| == Narrative summary (structure and content of John) == | |||

| {{Chapters in the Gospel of John}} | |||

| After the prologue ({{bibleverse-nb||John|1:1–5}}), the narrative of the gospel begins with verse 6, and consists of two parts. The first part (1:6-ch. 12) relates Jesus' public ministry from the time of his baptism{{fact}} by John the Baptist to its close. In this first part, John emphasizes seven of Jesus' miracles, always calling them "signs." The second part (ch. 13–21) presents Jesus in dialogue with his immediate followers (13–17) and gives an account of his ] and ] and of his appearances to the disciples after his ] (18–20). In Chapter 21, the "appendix", ] restores ] after his denial, predicts Peter's death, and discusses the death of the "beloved disciple". | |||

| ===Setting: the Johannine community debate=== | |||

| ], a scholar of the Johannine community, labelled the first and second parts the "Book of Signs" and the "Book of Glory", respectively.<ref></ref> | |||

| For much of the 20th century, scholars interpreted the Gospel of John within the paradigm of a hypothetical "]",{{sfn|Lamb|2014|p=2}} meaning that it was held to have sprung from a late-1st-century Christian community excommunicated from the Jewish synagogue (probably meaning the Jewish community){{sfn|Hurtado|2005|p=70}} on account of its belief in Jesus as the promised messiah.{{sfn|Köstenberger|2006|p=72}} This interpretation, which saw the community as essentially sectarian and outside the mainstream of early Christianity, has been increasingly challenged in the first decades of the 21st century,{{sfn|Lamb|2014|pp=2–3}} and there is currently considerable debate over the gospel's social, religious and historical context.{{sfn|Bynum|2012|pp=7, 12}} Nevertheless, the Johannine literature as a whole (made up of the gospel, the three Johannine epistles, and Revelation), points to a community holding itself distinct from the Jewish culture from which it arose while cultivating an intense devotion to Jesus as the definitive revelation of a God with whom they were in close contact through the ].{{sfn|Attridge|2008|p=125}} | |||

| ==Structure and content<!--'Book of Glory' and 'Book of glory' redirect here-->== | |||

| ===Hymn to the Word=== | |||

| {{Anchor|Structure and content}}<!-- There are several redirects to this section. Keep anchor to avoid messing them up. --> | |||

| This prologue identifies Jesus as the eternal Word (Logos) of God.<ref name="ODCC self">"John, Gospel of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005</ref> Thus John asserts Jesus' innate superiority over all divine messengers, whether angels or prophets.<ref name ="Harris"/> Here John adapts the doctrine of the Logos, God's creative principle, from Philo, a 1st-century Hellenized Jew.<ref name ="Harris"/> Philo, in turn, had adopted the term Logos from Greek philosophy, using it in place of the Hebrew concept of Wisdom (''sophia'') as the intermediary between the transcendent Creator and the material world.<ref name ="Harris"/> Some scholars argue that the prologue was taken over from an existing hymn and added at a later stage in the gospel's composition.<ref name="ODCC self"/> | |||

| ] to his 11 remaining disciples, from the ], 1308–1311]] | |||

| {{further|Prologue to John|Book of Signs|John 21}} | |||

| The majority of scholars see four sections in the Gospel of John: a ] (1:1–18); an account of the ministry, often called the "]" (1:19–12:50); the account of Jesus's final night with his disciples and the passion and resurrection, sometimes called the '''Book of Glory'''{{sfn|Moloney|1998|p=23}} or '''Book of Exaltation'''<!--boldface per WP:R#PLA--> (13:1–20:31);{{sfn|Köstenberger|2015|p=168}} and a conclusion (20:30–31); to these is added an epilogue that most scholars believe was not part of the original text (Chapter 21).{{sfn|Moloney|1998|p=23}} Disagreement does exist; some scholars, including Bauckham, argue that John 21 was part of the original work.{{sfn|Bauckham|2008|p=126}} | |||

| ===Seven Signs=== | |||

| This section recounts Jesus' public ministry.<ref name="ODCC self"/> It consists of seven miracles or "signs," interspersed with long dialogs and discourses, including several "I am" sayings.<ref name ="Harris"/> The miracles culminate with his most potent, raising Lazarus from the dead.<ref name ="Harris"/> In John, it is this last miracle, and not the temple incident, that prompts the authorities to have Jesus executed.<ref name ="Harris"/> Jesus' discourses identify him with symbols of major significance, "the bread of life" (John 6:35), "the light of the world" (John 8:12), "the door of the sheep" (John 10:7), "the good shepherd" (John 10:11), "the resurrection and the life" (John 14:6), and "the real vine" (John 15:1).<ref name ="Harris"/> Many scholars think that these claims represent the Christian community's faith in Jesus' divine authority but doubt that the historical Jesus actually made these sweeping claims.<ref name ="Harris"/> | |||

| *The prologue informs readers of the true identity of Jesus, the Word of God through whom the world was created and who took on human form;{{sfn|Aune|2003|p=245}} he came to the Jews and the Jews rejected him, but "to all who received him (the circle of Christian believers), who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God."{{sfn|Aune|2003|p=246}} | |||

| ===Last teachings and death=== | |||

| *Book of Signs (ministry of Jesus): Jesus calls his disciples and begins his earthly ministry.{{sfn|Van der Watt|2008|p=10}} He travels from place to place informing his hearers about God the Father in long discourses, offering eternal life to all who will believe, and performing miracles that prove the authenticity of his teachings, which creates tensions with the religious authorities (manifested as early as 5:17–18), who decide he must be eliminated.{{sfn|Van der Watt|2008|p=10}}{{sfn|Kruse|2004|p=17}} | |||

| This section opens with an account of the Last Supper that differs significantly from that found in the synoptics.<ref name ="Harris"/> Here, Jesus washes the disciples feet instead of ushering in a new covenant of his body and blood.<ref name ="Harris"/> John then devoted almost five chapters to farewell discourses.<ref name ="Harris"/> He declares his unity with the Father, promises to send the Paraclete, describes himself as the "real vine," explains that he must leave (die) before the Holy Spirit comes, and prays that his followers be one.<ref name ="Harris"/> John then records Jesus' arrest, trial, execution, and resurrection appearances, including "doubting Thomas."<ref name ="Harris"/> Significantly, John does not have Jesus claim to the the Son of God or the Messiah before the Sanhedrin or Pilate, and he omits the traditional earthquakes, thunder, and midday darkness that were said to accompany Jesus' death.<ref name ="Harris"/> John's revelation of divinity is Jesus' triumph over death, the eighth and greatest sign.<ref name ="Harris"/> | |||

| *The Book of Glory tells of Jesus's return to his heavenly father: it tells how he prepares his disciples for their lives without his physical presence and his prayer for himself and for them, followed by his betrayal, arrest, trial, crucifixion and post-resurrection appearances.{{sfn|Kruse|2004|p=17}} | |||

| *The conclusion sets out the purpose of the gospel, which is "that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."{{sfn|Edwards|2015|p=171}} | |||

| *Chapter 21, the addendum, tells of Jesus's post-resurrection appearances in Galilee, the ], the prophecy of the ], and the fate of the ].{{sfn|Edwards|2015|p=171}} | |||

| The structure is highly schematic: there are seven "signs" culminating in the ] (foreshadowing the ]), and seven "I am" sayings and discourses, culminating in Thomas's proclamation of the risen Jesus as "my Lord and my God" (the same title, {{lang|la|dominus et deus}}, claimed by the Emperor ], an indication of the date of composition).{{sfn|Witherington|2004|p=83}} | |||

| Chapter 21, in which the "beloved disciple" claims authorship, is commonly assumed to be an appendix, probably added to allay concerns after the death of the beloved disciple.<ref name ="Harris"/> There had been a rumor that the End would come before the beloved disciple died.<ref name = "May Metzger">May, Herbert G. and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.</ref> | |||

| ==Theology== | |||

| ===Detailed contents=== | |||

| ] is the oldest known New Testament fragment, dated to about 125–175 AD.<ref>Orsini, Pasquale, and Willy Clarisse (2012). , in: Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 88/4 (2012), pp. 443–474, '''p. 470''': "...Tab. 1, 𝔓{{sup|52}}, 125-175 AD, Orsini–Clarysse..."</ref>]] | |||

| The major events covered by the Gospel of John include: | |||

| ===Christology=== | |||

| {{col-begin|width=95%}} | |||

| {{Further|Christology}} | |||

| Scholars agree that while the Gospel of John clearly regards Jesus as divine, it just as clearly subordinates him to the one God.{{sfn|Hurtado|2005|p=53}} According to ], this Christology does not describe a subordinationist relation but rather the authority and validity of the Son's "revelation" of the Father, the continuity between the Father and the Son. Dunn sees this as intended to serve the Logos Christology,<ref name="Dunn">{{cite book |last1=Dunn |first1=James D. G. |title=Neither Jew nor Greek: A Contested Identity (Christianity in the Making, Volume 3) |date=2015 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing |isbn=978-1-4674-4385-2 |page=353 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dVZeCwAAQBAJ |language=ar}}</ref> while others (e.g., ]) see it as connected to John's ] theme.<ref name="Loke">Loke, Andrew. "A Kryptic Model of the Incarnation." Ashgate Publishing, 2014, pp. 28–30</ref> The idea of the ] developed only slowly through the merger of Hebrew monotheism and the idea of the messiah, Greek ideas of the relationship between God, the world, and the mediating Saviour, and the Egyptian concept of the three-part divinity.{{sfn|Hillar|2012|p=132}} But while the developed doctrine of the Trinity is not explicit in the books that constitute the ], the New Testament possesses a ] understanding of God{{sfn|Hurtado|2010|pp=99–110}} and contains a number of ]s.{{sfn|Januariy|2013|p=99}}<ref> | |||

| {{Col-break}} | |||

| ''Hymn to the Word'' | |||

| * ] (1:]–18) | |||

| ''Book of Signs'', ''Seven Signs'' | |||

| * ] (1:19–28, 3:22–36) | |||

| * ] (1:29–34) | |||

| * ] (1:35–51) | |||

| * ] (2:1–12) | |||

| * ] (2:13–25) | |||

| * ] the ] (3:1–21) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] (4) | |||

| * ] (5) | |||

| ** ] (5:24–29) | |||

| * ] (6:1–15) | |||

| * ] (6:16–21) | |||

| * ] (6:22–59) | |||

| ** ] (6:39–40, 44, 54, 11:24, 12:48) | |||

| * ] (6:60–71) | |||

| * Unbelief of ] (7:1–9) | |||

| * ] (7:10–44) | |||

| * Unbelief of ] leaders (7:45–52) | |||

| * ] (7:53–8:11) | |||

| * ] (8:12–20) | |||

| * Where I'm going, you can't come (8:21–30) | |||

| * The truth will make you free (8:31–38) | |||

| * Your father is the ] (8:39–47) | |||

| * Jesus existed before ] (8:48–59) | |||

| * ] man given sight (9) | |||

| * ] (10:1–21) | |||

| * ] (10:22–42, 12:37–43) | |||

| {{Col-break}} | |||

| * ] (11:1–44) | |||

| ** Let's return to ] (11:7) | |||

| ** ] (11:35) | |||

| * ] (11:45–57) | |||

| * ] (12:1–8) | |||

| * Plot to kill Lazarus (12:9–11) | |||

| * ] (12:12–19) | |||

| * ] (12:20–36) | |||

| * ] (12:44–50) | |||

| ''Book of Glory'', ''Last Teachings and Death'' | |||

| * ] (13:1–30) | |||

| * ] (13:31–35) | |||

| * ] (13:36–38, 18:15–18, 25–27) | |||

| * ] (14:1–14) | |||

| * Promise of the ] (14:15–31, 15:18–16:33) | |||

| * ] (15:1–17) | |||

| * ] (17) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ] (18:1–11) | |||

| * ] (18:12–14, 19–24) | |||

| * ] (18:28–19:16) | |||

| * ] (19:17–37) | |||

| * ] (19:38–42) | |||

| * ] (20:1–10) | |||

| * ] (20:11–18) | |||

| * ] (20:19–23) | |||

| * ] (20:24–29) | |||

| * Appendix (20:30–31) | |||

| * ] (21) | |||

| ** ] (21:1–14) | |||

| ** Prophecy of Peter's crucifixion (21:15–19) | |||

| ** ] (21:20–25) | |||

| {{Col-end}} | |||

| == Date and authorship == | |||

| {{main|Authorship of the Johannine works}} | |||

| === Authorship === | |||

| {{John}} | |||

| ], by ], c. 1475.]] | |||

| Most modern experts conclude the author to be an unknown non-eyewitness.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | {{cite book | ||

| |first = Archimandrite |last=Januariy | |||

| |title=Mary in the New Testament | |||

| |editor-last1 = Stewart | |||

| |first=Raymond Edward | |||

| |editor-first1 = Melville Y. | |||

| |last=Brown | |||

| |editor-link1 = Melville Y. Stewart | |||

| |coauthors= Paul J Achtemeier | |||

| |orig-date = 2003 | |||

| |isbn=0809121689 | |||

| |location= |

|location = Dordrecht | ||

| |chapter = The Elements of Triadology in the New Testament | |||

| |publisher=Paulist Press | |||

| |title = The Trinity: East/West Dialogue | |||

| |year=1978 | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=xJzdBgAAQBAJ | |||

| |pages=p. 198 | |||

| |series = Volume 24 of Studies in Philosophy and Religion | |||

| |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ML1mnUBwmhcC | |||

| |date = 2013 | |||

| |publisher = Springer Science & Business Media | |||

| |publication-date = 2013 | |||

| |page = 100 | |||

| |isbn = 978-94-017-0393-2 | |||

| |access-date = 21 December 2021 | |||

| |quote = Trinitarian formulas are found in New Testament books such as 1 Peter 1:2; and 2 Cor 13:13. But the formula used by John the mystery-seer is unique. Perhaps it shows John's original adaptation of Paul's dual formula. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| </ref> John's "high Christology" depicts Jesus as divine and preexistent, defends him against Jewish claims that he was "making himself equal to God",<ref>{{bibleverse|John|5:18}}</ref>{{sfn|Hurtado|2005|p=51}} and talks openly about his divine role and echoing ]'s "]" with seven "]" declarations of his own.{{sfn|Harris|2006|pp=302–10}}{{Efn|The declarations are: | |||

| </ref> | |||

| * "I am the ]"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|6:35|DRA|6:35}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am the ]"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|8:12|DRA|8:12}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am the gate for the sheep"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|10:7|DRA|10:7}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am the ]"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|10:11|DRA|10:11}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am the resurrection and the life"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|11:25|DRA|11:25}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am ]"<ref>{{bibleverse|John|14:6|DRA|14:6}}</ref> | |||

| * "I am the ]".<ref>{{bibleverse|John|15:1|DRA|15:1}}</ref>}} At the same time there is a stress like that in ] on the physical continuity of Jesus's resurrected body, as Jesus tells ]: "Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe."{{sfn|Cullmann|1965|p=11}}<ref>{{bibleverse|John|20:27}}</ref> | |||

| ===Logos=== | |||

| The authorship has been disputed since at least the second century, with mainstream Christianity traditionally holding that the author was ], son of Zebedee. Several other authors have historically been suggested, including ], ] and ], though many apologetic Christian scholars still hold to the conservative view that ascribes authorship to John the Apostle. | |||

| {{Main|Logos (Christianity)}} | |||

| {{see also|John 1:1|In the beginning (phrase)}} | |||

| In the prologue, the gospel identifies Jesus as the ] or Word. In ], the term {{transliteration|grc|]}} meant the principle of cosmic reason.{{sfn|Greene|2004|p=p37-}} In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of ], God's companion and intimate helper in creation.{{sfn|Dunn|2015|pp=350–351}} The ] philosopher ] merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God's creator of and mediator with the material world. According to ], the gospel adapted Philo's description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the ] of the Logos.{{sfn|Harris|2006|pp=302–310}} | |||

| Another possibility is that the title {{transliteration|grc|logos}} is based on the concept of the divine Word found in the ]s (Aramaic translation/interpretations recited in the synagogue after the reading of the Hebrew Scriptures). In the Targums (which all postdate the first century but which give evidence of preserving early material), the concept of the divine Word was used in a manner similar to Philo, namely, for God's interaction with the world (starting from creation) and especially with his people. Israel, for example, was saved from Egypt by action of "the Word of the {{LORD}}", and both Philo and the Targums envision the Word as manifested between the cherubim and the Holy of Holies.{{sfn|Ronning|2010|p=}} | |||

| The text itself is unclear about the issue. {{bibleverse||John|21:20–25}} contains information that could be construed as autobiographical. Conservative scholars generally assume that first person "I" in verse 25, ''the disciple'' in verse 24 and ''the disciple whom Jesus loved'' (also known as the ]) in verse 20 are the same person.<ref></ref> Critics point out that the abrupt shift from third person to first person in vss. 24–25 indicates that the author of the epilogue, who is supposed a third-party editor, claims the preceding narrative is based on the Beloved Disciple's testimony, while he himself is not the Beloved Disciple.<ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ===Cross=== | |||

| Ancient testimony is similarly conflicted. Attestation of Johannine authorship can be found as early as ].<ref name="ODCC self"/> ] wrote that Irenaeus received his information from ], who is said to have received it from the Apostles directly.{{fact}} ] argues that there is a solid early orthodox tradition of authorship: the tradition that an apostle of Jesus wrote the Gospel and can be attested to as early as the first two decades of the second century, and there are many ] in the remainder of the second century that ascribe the text to ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Hill |first=Charles E. |title=The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church |date=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press |place=New York |isbn=9780199291441 |pages= p. 473 |}}</ref> ] and ] similarly argue for ] as the author of the text.{{Fact|date=April 2007}} Hill goes on to propose that ], ], ]’ elders, and ]' ''Exegesis of the Lord’s Oracles'' possibly all quote from the Gospel of John. | |||

| The portrayal of Jesus's death in John is unique among the gospels. It does not appear to rely on the kinds of atonement theology indicative of vicarious sacrifice<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|10:45}}, {{bibleverse|Romans|3:25}}</ref> but rather presents Jesus's death as his glorification and return to the Father. Likewise, the Synoptic Gospels' three "passion predictions"<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|8:31}}, {{bibleverse|Mark|9:31}}, {{bibleverse|Mark|10:33–34}} and pars.</ref> are replaced by three instances of Jesus explaining how he will be exalted or "lifted up".<ref>{{bibleverse|John|3:14}}, {{bibleverse|John|8:28}}, {{bibleverse|John|12:32}}.</ref> The verb for "lifted up" ({{langx|grc|ὑψωθῆναι}}, {{transliteration|grc|hypsōthēnai}}) reflects the ] at work in John's theology of the cross, for Jesus is both physically elevated from the earth at the ] but also, at the same time, exalted and glorified.{{sfn|Kysar|2007a|pp=49–54}} | |||

| ===Sacraments=== | |||

| ], however, takes note of an ] sect, the '']'', who believed the Gospel was actually written by one ], a second-century Gnostic.<ref name="Panarion">Panarion 51.3.1–6</ref> Corroborating this evidence is a quotation by ] (History of the Church 7.25.2) in which ] (mid-third century) claims that the Apocalypse of John (known commonly as the ]), but not the Gospel of John, was believed by ''some before'' him (7.25.1) to also have been written by Cerinthus. This discussion of the Alogi represents the only instance in which both the Book of Revelation and the Gospel of John were specifically attributed to Cerinthus.<ref name="Panarion" /> Hill asserts that, at that time, the Gospel of John was never attributed to Cerinthus by the established orthodoxy; that Eusebius was only stating a theory that he had heard; and that Eusebius himself believed the Gospel to have been written by the Apostle John.<ref>Charles E. Hill. ''The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church'' Oxford Press p.{{Fact|date=May 2007}} ISBN 978-0199291441</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Sacrament}} | |||

| Scholars disagree on whether and how frequently John refers to ]s, but current scholarly opinion is that there are very few such possible references, and that if they exist they are limited to ] and the ].{{sfn|Bauckham|2015b|p=83–84}} In fact, there is no institution of the Eucharist in John's account of the ] (it is replaced by Jesus washing the feet of his disciples), and no New Testament text that unambiguously links baptism with rebirth.{{sfn|Bauckham|2015b|p=89,94}} | |||

| ===Individualism=== | |||

| Starting in the 19th century, critical scholarship has further questioned the apostle John's authorship, arguing that the work was written decades after the events it describes. The critical scholarship argues that there are differences in the composition of the Greek within the Gospel, such as breaks and inconsistencies in sequence, repetitions in the discourse, as well as passages that clearly do not belong to their context, and these suggest ].<ref>Ehrman 2004, p. 164–5</ref> | |||

| Compared to the synoptic gospels, John is markedly individualistic, in the sense that it places emphasis more on the individual's relation to Jesus than on the corporate nature of the Church.{{sfn|Bauckham|2015a}}{{sfn|Moule|1962|p=172}} This is largely accomplished through the consistently singular grammatical structure of various aphoristic sayings of Jesus.{{sfn|Bauckham|2015a}}{{Efn|{{harvnb|Bauckham|2015a}} contrasts John's consistent use of the third person singular ("The one who..."; "If anyone..."; "Everyone who..."; "Whoever..."; "No one...") with the alternative third person plural constructions the author could have used instead ("Those who..."; "All those who..."; etc.). He also notes that the sole exception occurs in the prologue, serving a narrative purpose, whereas the later aphorisms serve a "paraenetic function".}} Emphasis on believers coming into a new group upon their conversion is conspicuously absent from John,{{sfn|Bauckham|2015a}} and there is a theme of "personal coinherence", that is, the intimate personal relationship between the believer and Jesus in which the believer "abides" in Jesus and Jesus in the believer.{{sfn|Moule|1962|p=172}}{{sfn|Bauckham|2015a}}{{Efn|See {{bibleverse|John|6:56|DRA}}, {{bibleverse|John|10:14–15|DRA|10:14–15}}, {{bibleverse|John|10:38|DRA|10:38}}, and {{bibleverse|John|14:10, 17, 20, 23|DRA|14:10, 17, 20, and 23}}.}} John's individualistic tendencies could give rise to a ] achieved on the level of the individual believer, but this realized eschatology is not to replace "orthodox", futurist eschatological expectations, but to be "only correlative".{{sfn|Moule|1962|p=174}} | |||

| ===John the Baptist=== | |||

| ], a biblical scholar who specialized in studying the Johannine community, summarizes a prevalent theory regarding the development of this gospel.<ref>{{cite book |last=Brown |first=Raymond E. |authorlink=Raymond E. Brown |title=Introduction to the New Testament |year=1997 |publisher=Anchor Bible |location=New York |id=ISBN 0-385-24767-2 |pages=p. 363–4}}</ref> He identifies three layers of text in the Fourth Gospel (a situation that is paralleled by the ]s): 1) an initial version Brown considers based on personal experience of Jesus; 2) a structured literary creation by the evangelist which draws upon additional sources; and 3) the edited version that readers know today (Brown 1979). | |||

| {{Further|John the Baptist}} | |||

| John's account of John the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. In this gospel, John is not called "the Baptist."{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005}} John the Baptist's ministry overlaps with ]; his ] is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005}} The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus, and makes a vital theological use of it.{{sfn|Barrett|1978|p=16}} He subordinates John to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of John's sect who regarded the Jesus movement as an offshoot of theirs.{{sfn|Harris|2006|p=}} | |||

| In the Gospel of John, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus's ministry before John the Baptist was imprisoned and executed by ]. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The ] rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.{{sfn|Funk|1998|pp=365–440}} According to the biblical historians at the Jesus Seminar, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.{{sfn|Funk|1998|p=268}} | |||

| Among scholars, Ephesus in Asia Minor is a popular suggestion for the gospel's origin.<ref name ="Harris">], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> | |||

| === |

===Gnosticism=== | ||

| {{Further|Christian Gnosticism}} | |||

| In the first half of the 20th century, many scholars, especially ], argued that the Gospel of John has elements in common with ].{{sfn|Harris|2006|p=}} Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until the mid-2nd century, and so 2nd-century ] concentrated much effort in examining and refuting it.{{sfn|Olson|1999|p=36}} To say the Gospel of John contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author to respond to it.{{sfn|Kysar|2005|pp=88ff}} Bultmann, for example, argued that the opening theme of the Gospel of John, the preexisting Logos, along with John's duality of light versus darkness, were originally Gnostic themes that John adopted. Other scholars (e.g., ]) have argued that the preexisting Logos theme arises from the more ancient Jewish writings in the eighth chapter of the ], and was fully developed as a theme in Hellenistic Judaism by ].{{sfn|Brown|1997}} The discovery of the ] at ] verified the Jewish nature of these concepts.{{sfn|Charlesworth|2010|p=42}} ] suggested reading John 8:56 in support of a Gnostic theology,{{sfn|DeConick|2016|pp=13–}} but recent scholarship has cast doubt on her reading.{{sfn|Llewelyn|Robinson|Wassell|2018|pp=14–23}} | |||

| Gnostics read John but interpreted it differently from non-Gnostics.{{sfn|Most|2005|pp=121ff}} Gnosticism taught that salvation came from '']'', secret knowledge, and Gnostics saw Jesus as not a savior but a revealer of knowledge.{{sfn|Skarsaune|2008|pp=247ff}} The gospel teaches that salvation can be achieved only through revealed wisdom, specifically belief in (literally belief {{em|into}}) Jesus.{{sfn|Lindars|1990|p=62}} John's picture of a supernatural savior who promised to return to take those who believed in him to a heavenly dwelling could be fitted into Gnostic views.{{sfn|Brown|1997|p=375}} It has been suggested that similarities between the Gospel of John and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish ].{{sfn|Kovacs|1995}} | |||

| Most scholars agree on a range of ''c.'' 90–100 for when the gospel was written, though dates as early as the 60s or as late as the 140s have been advanced by a small number of scholars. ] quoted from the gospel of John, which would also support that the Gospel was in existence by at least the middle of the second century,<ref> ''NTCanon.org''. Retrieved ], ].</ref> and the ], which records a fragment of this gospel, is usually dated between 125 and 160 CE.<ref>Nongbri, Brent, 2005. "The Use and Abuse of P52: Papyrological Pitfalls in the Dating of the Fourth Gospel." Harvard Theological Review 98:23–52.</ref> | |||

| ==Comparison with other writings== | |||

| The traditional view is supported by reference to the statement of ] that John wrote to supplement the accounts found in the other gospels (], ''Ecclesiastical History'', 6.14.7). This would place the writing of John's gospel sufficiently after the writing of the synoptics. | |||

| ] rendition of St. John the Evangelist, from the ].]] | |||

| ===Synoptic gospels and Pauline literature=== | |||

| Conservative scholars consider internal evidences, such as the lack of the mention of the destruction of the temple and a number of passages that they consider characteristic of an eye-witness (John 13:23ff, 18:10, 18:15, 19:26–27, 19:34, 20:8, 20:24–29), sufficient evidence that the gospel was composed before 100 and perhaps as early as 50–70. Barrett suggests an earliest date of 90, based on familiarity with Mark’s gospel, and the late date of a ] (which is a theme in John).<ref>Barrett, C. K. ''The Gospel According to St. John.'', p.127–128</ref> Morris suggests 70, given Qumran parallels and John’s turns of phrase, such as "his disciples" vs. "the disciples".<ref>Morris, L. ''The Gospel According to John'' p.59</ref> ] proposes an initial edition by 50–55 and then a final edition by 65 due to narrative similarities with ].<ref>Robinson, J. A. T. ''Redating the Gospels'', pp. 284, 307</ref> | |||

| The Gospel of John is significantly different from the ] in the selection of its material, its theological emphasis, its chronology, and literary style, with some of its discrepancies amounting to contradictions.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–237}} The following are some examples of their differences in just one area, that of the material they include in their narratives:{{sfn|Köstenberger|2013|p=unpaginated}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| There are critical scholars who are of the opinion that John was composed in stages (probably two or three), beginning at an unknown time (50–70?) and culminating in a final text around 95–100. This date is assumed in large part because ], the so-called "appendix" to John, is largely concerned with explaining the death of the "beloved disciple", supposedly the leader of the Johannine community that would have produced the text. If this leader had been a follower of Jesus, or a disciple of one of Jesus' followers, then a death around 90–100 is reasonable. | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Material unique to the synoptic gospels !! Material unique to the fourth gospel | |||

| |- | |||

| | Narrative parables || Symbolic discourses | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] and ] || Dialogues and monologues | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || Overt messianism | |||

| |- | |||

| | Sadducees, elders, lawyers || The "]" | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] of ] || ] of ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || John witnessing Jesus | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] and ] || No mention of hell | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] prologue | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || "]" | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || Seven "I Am" declarations | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || Promise of the ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] || ] | |||

| |} | |||

| In the Synoptics, the ministry of Jesus takes a single year, but in John it takes three, as evidenced by references to three Passovers. Events are not all in the same order: the date of the crucifixion is different, as is the time of Jesus' anointing in Bethany and the ], which occurs in the beginning of Jesus' ministry rather than near its end.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}} | |||

| === Textual history and manuscripts === | |||

| ] is the earliest manuscript fragment found of John's Gospel; dated to about 125.]] | |||

| Many incidents from John, such as the wedding in Cana, the encounter of Jesus with the Samaritan woman at the well, and the ], are not paralleled in the synoptics, and most scholars believe the author drew these from an independent source called the "]", the speeches of Jesus from a second "discourse" source,{{sfn|Reinhartz|2017|p=168}}{{sfn|Fredriksen|2008|p=unpaginated}} and the prologue from an early hymn.{{sfn|Perkins|1993|p=109}} The gospel makes extensive use of the Jewish scriptures:{{sfn|Reinhartz|2017|p=168}} John quotes from them directly, references important figures from them, and uses narratives from them as the basis for several of the discourses. The author was also familiar with non-Jewish sources: the Logos of the prologue (the Word that is with God from the beginning of creation), for example, was derived from both the Jewish concept of Lady Wisdom and from the Greek philosophers, John 6 alludes not only to ] but also to Greco-Roman mystery cults, and John 4 alludes to ] messianic beliefs.{{sfn|Reinhartz|2017|p=171}} | |||

| The earliest known ]s of the New Testament is a fragment from John, ]. A scrap of papyrus roughly the size of a business card discovered in Egypt in 1920 (now at the ], ], accession number P52) bears parts of {{bibleverse||John|18:31–33}} on one side and {{bibleverse||John|18:37–38}} on the other. Most texts list the date of this manuscript to ''c.'' 125.<ref>{{cite book |author=by Bruce M. Metzger |title=The text of the New Testament: its transmission, corruption, and restoration |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |year=1992 |pages= |isbn=0-19-507297-9 |pages=p.56}} | |||

| John lacks scenes from the Synoptics such as Jesus's baptism,{{sfn|Funk|Hoover|1993|pp=1–30}} the calling of the Twelve, exorcisms, parables, and the Transfiguration. Conversely, it includes scenes not found in the Synoptics, including Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, the resurrection of Lazarus, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, and multiple visits to Jerusalem.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}} | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland |title=The Text of the New Testament an Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company |location= |year= |pages= |isbn=0-8028-4098-1 |pages=p.99}}</ref> The difficulty of fixing the date of a fragment based solely on paleographic evidence allows for a range of dates that extends from before 100 to well into the second half of the second century. P52 is small, and although a plausible reconstruction can be attempted for most of the fourteen lines represented, nevertheless the proportion of the text of the Gospel of John for which it provides a direct witness is necessarily limited, so it is rarely cited in textual debate.<ref>Tuckett, p. 544; http://www.skypoint.com/~waltzmn/ManuscriptsPapyri.html#P52; http://www.historian.net/P52.html.</ref> Other notable early manuscripts include ] and ]. | |||

| In the fourth gospel, Jesus's mother ] is mentioned in three passages but not named.{{sfn|Williamson|2004|p=265}}{{sfn|Michaels|1971|p=733}} John does assert that Jesus was known as the "son of ]" in ].<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|6:42|DRA}}</ref> For John, Jesus's town of origin is irrelevant, for he comes from beyond this world, from ].{{sfn|Fredriksen|2008}} | |||

| Much current research on the textual history of the Gospel of John is being done by the ]. | |||

| While John makes no direct mention of Jesus's baptism,{{sfn|Funk|Hoover|1993|pp=1–30}}{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}} he does quote ]'s description of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a ], as happens at Jesus's baptism in the Synoptics.{{sfn|Zanzig|1999|p=118}}{{sfn|Brown|1988|pp=25-27}} Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including the ] and the ],{{sfn|Pagels|2003}} and the ] are not mentioned.{{sfn|Funk|Hoover|1993|pp=1–30}}{{sfn|Thompson|2006|p=184}} John does not list the ] and names at least one disciple, ], whose name is not found in the Synoptics. ] is given a personality beyond a mere name, described as "]".{{sfn|Most|2005|p=80}} | |||

| == Source criticism == | |||

| {{Further|]}} | |||

| Jesus is identified with the Word ("]"), and the Word is identified with {{transliteration|grc|theos}} ("god" in Greek);{{sfn|Ehrman|2005}} the Synoptics make no such identification.{{sfn|Carson|1991|p=117}} In Mark, Jesus urges his disciples to keep his divinity secret, but in John he is very open in discussing it, even calling himself "I AM", the title God gives himself in ] at his self-revelation to ]. In the Synoptics, the chief theme is the ] and the ] (the latter specifically in Matthew), while John's theme is Jesus as the source of eternal life, and the Kingdom is only mentioned twice.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}}{{sfn|Thompson|2006|p=184}} In contrast to the synoptic expectation of the Kingdom (using the term {{transliteration|grc|]}}, meaning "coming"), John presents a more individualistic, ].{{Sfn|Moule|1962|pp=172–74}}{{efn|''Realized eschatology'' is a ] theory popularized by ] (1884–1973). It holds that the eschatological passages in the ] do not refer to future events, but instead to the ] and his lasting legacy.{{sfn|Ladd|Hagner|1993|p=56}} In other words, it holds that Christian eschatological expectations have already been realized or fulfilled.}} | |||

| Source criticism is the practice of deducing an author's or redactor's sources, especially in Biblical criticism. | |||

| In the Synoptics, quotations of Jesus are usually in the form of short, pithy sayings; in John, longer quotations are often given. The vocabulary is also different, and filled with theological import: in John, Jesus does not work "miracles", but "signs" that unveil his divine identity.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}} Most scholars consider John not to contain any ]s. Rather, it contains ]ical stories or ], such as those of the ] and the ], in which each element corresponds to a specific person, group, or thing. Other scholars consider stories like the childbearing woman<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|16:21|DRA}}</ref> or the dying grain<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|12:24|DRA}}</ref> to be parables.{{efn|See {{harvnb|Zimmermann|2015|pp=333–60}}.}} | |||

| ===Signs gospel=== | |||

| In 1941 ] suggested<ref>''Das Evangelium des Johannes'', 1941 (translated as ''The Gospel of John: A Commentary,'' 1971)</ref> that the author of John depended in part on an oral miracles tradition or manuscript account of Christ's miracles that was independent of, and not used by, the synoptic gospels. This hypothetical "]" is alleged to have been circulating before ]. Its traces can be seen in the remnants of a numbering system associated with some of the miracles that appear in the ''Gospel of John'': all of the miracles that are mentioned only by John occur in the presence of John; the "signs" or ''semeia'' (the expression is uniquely John's) are unusually dramatic; and they are accomplished in order to call forth faith (see {{bibleverse||John|12:37}}). These miracles are different both from the rest of the "signs" in John, and from the miracles in the synoptic gospels, which occur as a ''result'' of faith. Bultmann's conclusion that John was reinterpreting an early Hellenistic tradition of Jesus as a wonder-worker, a "magician" within the Hellenistic world-view, was so controversial that ] proceedings were instituted against him and his writings. (See more detailed discussions linked below.) | |||

| According to the Synoptics, Jesus's arrest was a reaction to the cleansing of the temple; according to John, it was triggered by the raising of Lazarus.{{sfn|Burge|2014|pp=236–37}} The ], portrayed as more uniformly legalistic and opposed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels, are portrayed as sharply divided; they frequently debate. Some, such as ], even go so far as to be at least partially sympathetic to Jesus. This is believed to be a more accurate historical depiction of the Pharisees, who made debate one of the tenets of their belief system.{{sfn|Neusner|2003|p=8}} | |||

| ===Egerton gospel=== | |||

| The mysterious ] appears to represent a parallel but independent tradition to the Gospel of John. According to scholar Ronald Cameron, it was originally composed some time between the middle of the first century and early in the second century, and it was probably written shortly before the Gospel of John.<ref>Ronald Cameron, editor. ''The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts'', 1982</ref> ], et al, places the Egerton fragments in the 2nd century, perhaps as early as 125, which would make it as old as the oldest fragments of John.<ref>], Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. ''The five gospels.'' HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. page 543.</ref> | |||

| In place of the communal emphasis of the Pauline literature, John stresses the personal relationship of the individual to God.{{sfn|Bauckham|2015a}} | |||

| == Characteristics of the Gospel of John == | |||

| ===Johannine literature=== | |||

| The ''Gospel of John'' is easily distinguished from the three ], which share a considerable amount of text. John omits about 90% of the material in the synoptics. The synoptics describe much more of Jesus' life, miracles, ], and exorcisms. However, the materials unique to John are notable, especially in their effect on modern Christianity. | |||

| The Gospel of John and the three ] exhibit strong resemblances in theology and style; the ] has also been traditionally linked with these, but differs from the gospel and letters in style and even theology.{{sfn|Van der Watt|2008|p=1}} The letters were written later than the gospel, and while the gospel reflects the break between the Johannine Christians and the Jewish synagogue, in the letters the Johannine community itself is disintegrating ("They went out from us, but they were not of us; for if they had been of us, they would have continued with us; but they went out..." - 1 John 2:19).{{sfn|Moloney|1998|p=4}} This secession was over ], the "knowledge of Christ", or more accurately the understanding of Christ's nature, for the ones who "went out" hesitated to identify Jesus with Christ, minimising the significance of the earthly ministry and denying the salvific importance of Jesus's death on the cross.{{sfn|Watson|2014|p=112}} The epistles argue against this view, stressing the eternal existence of the Son of God, the salvific nature of his life and death, and the other elements of the gospel's "high" Christology.{{sfn|Watson|2014|p=112}} | |||

| === |

===Historical reliability=== | ||

| {{More citations needed section|date=July 2021}}{{Further|Historicity of the Bible}} | |||

| Jesus's teachings in the Synoptics greatly differ from those in John. Since the 19th century, scholars have almost unanimously accepted that the Johannine discourses are less likely to be historical than the synoptic parables, and were likely written for theological purposes.{{sfn|Sanders|1995|pp=57, 70–71}} Nevertheless, they generally agree that John is not without historical value. Some potential points of value include early provenance for some Johannine material, topographical references for ] and ], Jesus's crucifixion occurring prior to the Feast of Unleavened Bread, and his arrest in the ] occurring after the accompanying deliberation of Jewish authorities.{{sfn|Theissen|Merz|1998|pp=36–37}}{{sfn|Brown|Fitzmyer|Murphy|1999|pp=815,1274}}{{sfn|Brown|1994|p=}} | |||

| Recent scholarship has argued for a more favourable reappraisal of the historical value of the Gospel of John and its importance for the reconstruction of the historical Jesus, based on recent archaeological and literary studies.{{sfn|Charlesworth|Pruszinski|2019|pp=1–3}}{{sfn|Blomberg|2023|pp=179ff}} | |||

| John portrays Jesus Christ as "a brief manifestation of the eternal Word, whose immortal spirit remains ever-present with the believing Christian."<ref name="stephenharris">]. ''Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction'', 2nd ed. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. page 304.</ref> The gospel gives far more focus to the mystical relation of the Son to the Father. Many have used his gospel for the development of the concept of the ] while the Synoptic Gospels focused less directly on Jesus as the ]. John includes far more direct claims of Jesus being the only Son of God than the Synoptic Gospels. The gospel also focuses on the relation of the Redeemer to believers, the announcement of the Holy Spirit as the Comforter (Greek '']''), and the prominence of ] as an element in the Christian character. | |||

| ==Representations== | |||

| Some critics have maintained that the opening ] declares that the Logos is "god" or "a god" (Greek: theos, without the article) and was with "God" (Greek: pros ton theon), but not that the Logos is God (Greek: ho theos).<ref>]. ]: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4; See also ]'s ''Commentary on the Gospel of John''.</ref> The translators of the New International Version (and Today's New International Version), the New American Standard Bible, the Amplified Bible, the New Living Translation, the King James Version, Young's Literal Translation, the Darby Translation, and the Wycliffe New Testament, to name a few, all disagree with these critics. | |||

| ] translating the Gospel of John on his deathbed'', by ], 1902|alt=Bede translating the Gospel of John on his deathbed, by James Doyle Penrose, 1902. Depicts the Venerable Bede as an elderly man with a long, white beard, sitting in a darkened room and dictating his translation of the Bible, as a younger scribe, sitting across from him, writes down his words. Two monks, standing together in the corner of the room, look on.]] | |||

| The gospel has been depicted in live narrations and dramatized in productions, ], ], and ]s, as well as in film. The most recent such portrayal is the 2014 film ''The Gospel of John'', directed by David Batty and narrated by ] and ], with ] as Jesus.{{update inline|date=August 2021}} The 2003 film '']'' was directed by ] and narrated by ], with ] as Jesus. | |||

| === Jews === | |||

| Parts of the gospel have been set to music. One such setting is ]'s power anthem "Come and See", written for the 20th anniversary of the Alliance for Catholic Education and including lyrical fragments taken from the ]. Additionally, some composers have made settings of the ] as portrayed in the gospel, most notably ]'s '']'', although some of its verses are from ]. | |||

| The Gospel’s treatment of the role of the Jewish authorities in the ] has given rise to allegations of ]. The Gospel often employs the title "the Jews" when discussing the opponents of Jesus. The meaning of this usage has been the subject of debate, though critics of the “anti-Semitic” theory cite that the author most likely considered himself Jewish and was probably speaking to a largely Jewish community. Hence it is argued that "the Jews" properly refers to the Jewish religious authorities (see: ]), and not the Jewish people as a whole. It is because of this controversy that some modern English translations, such as ], remove the term "Jews" and replace it with more specific terms to avoid anti-Semitic connotations, citing the above argument. Most critics of these translations, conceding this point, argue that the context (since it is obvious that Jesus, John himself, and the other disciples were all Jews) makes John's true meaning sufficiently clear, and that a literal translation is preferred. | |||

| Other critics go further, arguing that the text displays a shift in emphasis away from the Roman provincial government, which actually carried out the execution, and to the Jewish authorities as a technique used to render a developing Christianity more palatable in official circles. Nevertheless, these passages have been historically used by some Christian groups to justify the persecution of Jews. | |||

| === Gnostic elements === | |||

| Though not commonly understood as Gnostic, John has elements in common with ].<ref>], Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.</ref> Gnostics must have read John because it is found with Gnostic texts. The root of Gnosticism is that salvation comes from gnosis, secret knowledge. The nearly five chapters of the "farewell discourses" (John , ) Jesus shares only with the ]. Jesus pre-exists birth as the Word (]). This origin and action resemble a gnostic ] (emanation from God) being sent from the ] (region of light) to give humans the knowledge they need to ascend to the pleroma themselves. John's denigration of the flesh, as opposed to the spirit, is a classic Gnostic theme. | |||

| It has been suggested that similarities between John's Gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish ].Kovacs, Judith L. (1995).<ref>Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus’ Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20–36. Journal of Biblical Literature 114(2), 227–247.</ref> | |||

| === Thomas === | |||

| In John, the apostle Thomas appears at one point as brave ({{Bibleverse-nb||John|11:16|9}}), at another as "doubting Thomas" ({{Bibleverse-nb||John|20:25|9}}). He doubts that Jesus has risen physically from the grave, and Jesus proves that he has. While the tradition of John was popular in Asia Minor, the tradition of Thomas was popular in neighboring Syria. To him was attributed a version of Jesus' teachings with ] elements, which appears in the Gospel of Thomas. In John, the author uses Thomas himself to demonstrate that Jesus rose in the flesh. | |||

| === Differences from the Synoptic Gospels === | |||

| {{seealso|Omissions in the Gospel of John}} | |||

| John is significantly different from the ] in many ways. Some of the differences are: | |||

| * The Gospel of John contains 4 visits by Jesus to Jerusalem, each with a Passover celebration. This chronology suggests Jesus' public ministry lasted 3 years. In the synoptic gospels, Jesus makes one trip to Jerusalem in time for the Passover observance. | |||

| * The ] is only mentioned twice in John ({{bibleverse-nb||John|3:3–5}}). In contrast, the other gospels repeatedly use the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven as important concepts. John's Jesus claims a kingdom of his own, not of this world: {{bibleverse-nb||John|18:36}}. See also ]. | |||

| * John does not contain any ]s, that is poetic stories each illustrating a single message or idea.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11460a.htm | title=Catholic Encyclopedia: Parables |accessdate=2008-02-01}}</ref> Rather it contains ]ic stories or ], such as ] and ], in which each individual element corresponds to a specific group or thing. The ] ''Greek New Testament''<ref>edited by ], ] and other scholars</ref> titles {{bibleverse||John|10:1–6}} as "The Parable of the Sheepfold", but {{bibleverse||John|10:7}} continues as a metaphor: "I am the gate". | |||

| * The saying "He who has ears, let him hear" is absent from John. | |||

| * The ] are never mentioned as in the Synoptics. | |||

| * The Synoptics contain a wealth of stories about ], but John does not have as many of those stories; John tends to elaborate more heavily on its stories than do the Synoptics. | |||

| * Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including all of the ] and the ] and the instructions that Jesus gave to his disciples when he sent them out throughout the country to heal and preach (as in {{bibleverse||Matthew|10}} and {{bibleverse||Luke|10}}). Instead the major speeches according to John are at the Sea of Galilee {{bibleverse-nb||John|6:22–71}}, the temple {{bibleverse-nb||John|7:14–8:59}}, and the last supper {{bibleverse-nb||John|13–17}}. | |||

| * ] appears near the beginning of the work. In the Synoptics this occurs late in Jesus' ministry. | |||

| * Most of the action in John takes place in ] and Jerusalem; only a few events occur in ], and of those, only the feeding of the multitude (6:1–16) and the trip across the Sea of Galilee (6:17–21) are also found in the Synoptics. | |||

| * According to the ]<ref>Catholic Book Publishing Co., New York, 1970</ref>, the ] ({{bibleverse||John|8:1–11}}) is missing from the best early Greek manuscripts. When it does appear it is at different places: here, after John 7:36 or at the end of this gospel. It can also be found after Luke 21:38. | |||

| * The ] is recorded as ] 14 ({{bibleverse-nb||John|19:14}}), the day of preparation for the Passover, about noon, in contrast to the synoptic Nisan 15. The difference led to schism in the early church (see ]). This would mean there were two sabbath days between Jesus' crucifixion and the morning of his resurrection as the Passover festival had additional Sabbaths.{{Fact|date=March 2008}} | |||

| * The earthquake and the ], prominent in the Synoptics, are missing. | |||

| * Jesus does not utter ] prophecies. | |||

| === Characteristics unique to John === | |||

| <!-- the trivial ones should be omitted --> | |||

| * The Apostle ] is given a personality beyond a mere name, as "Doubting Thomas" ({{bibleverse||John|20:27}} etc). | |||

| * Jesus refers to himself with "εγω ειμι" "I am" seven times ({{bibleverse||John|6:35}}) ({{bibleverse||John|8:12}}) ({{bibleverse||John|10:9}}) ({{bibleverse||John|10:11}}) ({{bibleverse||John|11:25}}) ({{bibleverse||John|14:6}}) ({{bibleverse||John|15:1}}), beyond the common meaning, ] see this as an allusion to {{bibleverse||Exodus|3:14}} and thus a claim to divinity, i.e. ]. ] argues that the "I Am" statements are not self-reflexive on Jesus, but refer to "I Am" as a ].{{Fact|date=February 2008}} | |||

| * In the ], ] refuses to give any sign that he is the ], which is known as the ], for example {{bibleverse||Mark|8:11–12}}. In the ] and ], only the ''Sign of Jonah'' will be given ({{bibleverse||Matthew|12:38–39}}, {{bibleverse-nb||Matthew|16:1–4}}, {{bibleverse||Luke|11:29–30}}). The Gospel of John on the other hand has Jesus providing many signs, such as {{bibleverse-nb||John|2:11}} and {{bibleverse-nb||John|2:18–19}} and {{bibleverse-nb||John|12:37}}. | |||

| * Each "sign" corresponds to one of the metaphoric "εγω ειμι" "I am" sayings ({{bibleverse||John|6:1–11}}) ({{bibleverse||John|9:1–11}}) ({{bibleverse||John|5:2–9}}) ({{bibleverse||John|11:1–45}}) ({{bibleverse||John|4:46–54}}) ({{bibleverse||John|2:1–11}}) For example, the multiplication of bread corresponds to "I am the bread of life" | |||

| * Two "signs" are numbered—"the first sign," ({{bibleverse||John|2:11}}), and "the second sign," ({{bibleverse||John|4:54}})—but there are two other signs that occur in between these. Scholars conclude that this strange numbering occurs because John had access to a source, probably written, that consisted of the "signs" of Jesus in some numbered order. In between the first and second signs found in John's "Sign source", known as the ], John added his own, but did not account for his additions by numbering. | |||

| * There are no stories about ], ] or ], no predictions of ], though there is mention of the ] ({{bibleverse-nb||John|6:39–40}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|6:44}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|6:54}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|11:24}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|12:48}}), no ], no ethical teachings such as the ] other than ] ({{bibleverse-nb||John|13:31–35}}), or ] teachings other than perhaps {{bibleverse-nb||John|15:18–16:4}}. | |||

| * The ] is given: Greek text: about the tenth hour, translated as "four o'clock in the afternoon" ({{bibleverse||John|1:39}}) | |||

| * When the water at the ] is moved by an angel it heals ({{bibleverse||John|5:3–4}}) | |||

| * Jesus washes the disciples' feet ({{bibleverse||John|13:3–16}}) | |||

| * At Chapter 13 there is the description of the ] but, unlike the Synoptic Gospels (Mat 26:26–29; Mar 14:22–26, Luke 22:14–20) there is no formal institution of the ], whereas the prediction of Judas' betrayal is amply reported ({{bibleverse-nb||John|13:21–32}}). | |||

| * No other women are mentioned going to the tomb with Mary Magdalene. ({{bibleverse||John|20:1}}) | |||

| * Mary Magdalene visits the empty tomb twice. She believes ]. The second time she sees two angels. They do not tell her Jesus is risen. They only ask why she is crying. Mary mistakes Jesus for the gardener. He tells Mary ''not to'' touch or cling to him. ({{bibleverse||John|20:17}}). About a week later (some translations give "eight days later"), in the same chapter ({{bibleverse||John|20:28}}), Jesus asks Thomas to touch him and to place his fingers and hand in Jesus' still open wounds. At the sight of Jesus, Thomas gives an exclamation of faith but if he follows Jesus' direction, it is not in the text. | |||

| * Some of the brethren thought the ] would not die, and an explanation is given for his death. ({{bibleverse||John|21:23}}) | |||

| * The "disciple whom Jesus loved" wrote down things he had witnessed, and his testimony is asserted by a third party to be true ({{bibleverse||John|21:24}}) | |||

| * The beloved disciple (traditionally believed to be the Apostle John) is never named. | |||

| * When speaking, prior to his message, Jesus says "verily" twice, (25 times, starting with {{bibleverse-nb||John|1:51|KJV}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|3:3|KJV}}, {{bibleverse-nb||John|3:5|KJV}}… , see also ]), rather than just once as in the Synoptic Gospels. | |||

| * Jesus carried his own cross ({{bibleverse-nb||John|19:17}}); in the synoptics the cross was carried by ] ({{bibleverse||Mark|15:21}}, {{bibleverse||Matthew|27:32}}, {{bibleverse||Luke|23:26}}). | |||

| === Critical scholarship on the differences between John and the synoptics === | |||

| Since the advent of critical scholarship, John's historical importance has been considered less significant than the synoptic traditions by some scholars. The scholars of the 19th century concluded that the Gospel of John had little historical value. Over the next two centuries scholars such as Bultmann and Dodd looked closer and began finding historically important parts of John. Many scholars today believe that parts of John represent an independent historical tradition from the synoptics, while other parts represent later traditions.<ref>Brown 1997, p. 362–364</ref> The scholars of the ] still assert that there is little historical value in John, and consider nearly every Johannine saying of Jesus to be nonhistorical.<ref></ref> However, most scholars agree that John is a very important document on Christian theology. | |||

| ] comments: "few scholars would regard John as a source for information regarding Jesus' life and ministry in any degree comparable to the Synoptics". <ref>James D. G. Dunn, ''Jesus Remembered'', Eerdmans (2003), page 165</ref> | |||

| But ] says: "Gone are the days when it was scholarly orthodoxy to maintain that John was the least reliable of the gospels historically." It has become generally accepted that certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, that John's knowledge of things around ] is often superior to the synoptics, and that his presentation of Jesus' agony in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically accurate than their synoptic parallels.<ref>Henry Wansbrough, ''The Four Gospels in Synopsis'', The Oxford Bible Commentary, pp. 1012-1013, Oxford University Press 2001 ISBN 0198755007</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| John was written somewhere near the end of the first century, probably in ], in ]. The tradition of John the Apostle was strong in Anatolia, and ] reportedly knew him. Like the previous gospels, it circulated separately until Irenaeus proclaimed all four gospels to be scripture. | |||

| In the early church, John's reference to Jesus as the eternal Logos was a popular definition of Jesus, defeating the rival view that Jesus had been born a man ]. The gospel's description of Jesus' divinity was fundamental to the developing doctrine of the ]. | |||

| In the second century, Montanus of Phrygia launched ] in which he claimed to be the ] promised in John. | |||

| ] translated John into its ], replacing various older translations. | |||

| Although very much in line with many stories in the Synoptic Gospels and probably primitive (the ] definitely refers to it and it was probably known to ]), the ] is not part of the original text of the Gospel of John.<ref name ="Oxford">Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005</ref> The evidence for this view does not convince all scholars.<ref>"If it is not an original part of the Fourth Gospel, its writer would have to be viewed as a skilled Johannine imitator, and its placement in this context as the shrewdest piece of interpolation in literary history!" The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text with Apparatus: Second Edition, by Zane C. Hodges (Editor), Arthur L. Farstad (Editor) Publisher: Thomas Nelson; ISBN-10: 0840749635</ref> | |||

| When Bible criticism developed in the 19th century, John came under increasing criticism as less historically reliable than the synoptics. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{columns list|colwidth=22em| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| == |

== Notes == | ||

| {{ |

{{Notelist|30em}} | ||

| ==References== | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Ehrman |first=Bart D.|authorlink=Bart D. Ehrman |title=The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings |year=2004 |publisher=Oxford |location=New York |id=ISBN 0-19-515462-2 }} | |||

| {{refbegin|30em|indent=yes}} | |||

| * Raymond E. Brown, ''The Gospel According to John'' Anchor Bible, 1966, 1970 | |||

| * {{Cite book |author-last=Attridge |author-first=Harold W. |author-link=Harold W. Attridge |year=2008 |chapter=Part II: The Jesus Movements – Johannine Christianity |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6UTfmw_zStsC&pg=PA125 |editor1-last=Mitchell |editor1-first=Margaret M. |editor1-link=Margaret M. Mitchell |editor2-last=Young |editor2-first=Frances M. |editor2-link=Frances Young |title=The Cambridge History of Christianity, Volume 1: Origins to Constantine |location=] |publisher=] |pages=125–143 |doi=10.1017/CHOL9780521812399.008 |isbn=978-1-139-05483-6}} | |||

| * Raymond E. Brown, ''The Community of the Beloved Disciple'' Paulist Press, 1979 | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| * Robin M. Jensen, ''The Two Faces of Jesus'', Bible Review October 2002, p42 | |||

| |last = Aune | |||

| * ] & A.H. McNeile, ''A Critical and Exegetical Commentary On The Gospel According To St. John''. Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark, 1953. | |||

| |first = David E. | |||

| * ] ''Bethany – Discovering Christ's Love in Times of Suffering When Heaven Seems Silent'', (a study of John 12) Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846857027 | |||

| |author-link = David Aune | |||

| |chapter = John, Gospel of | |||

| == External links == | |||

| |title = The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric | |||

| {{wikisource|Bible (King James)/John|Gospel of John (KJV)}} | |||

| |publisher = Westminster John Knox Press | |||

| {{wikibooks}} | |||

| |year = 2003 | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=nhhdJ-fkywYC | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-664-21917-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| | last = Barrett | first = C. K. | |||

| | author-link = C. K. Barrett | |||

| | title = The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 1978 | |||

| | location = Philadelphia | |||

| | edition = 2nd | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-664-22180-5 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tWR8DJ6C8KsC | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| |last1 = Barton | |||

| |first1 = Stephen C. | |||

| |editor1-last = Bauckham | |||

| |editor1-first = Richard | |||

| |editor1-link = Richard Bauckham | |||

| |editor2-last = Mosser | |||

| |editor2-first = Carl | |||

| |title = The Gospel of John and Christian Theology | |||

| |publisher = Eerdmans | |||

| |year = 2008 | |||

| |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=3b2I8v2Gh8oC | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-8028-2717-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite book | |||

| |last1 = Bauckham | |||

| |first1 = Richard | |||

| |chapter = The Fourth Gospel as the Testimony of the Beloved Disciple | |||

| |chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=3b2I8v2Gh8oC&pg=PA126 | |||

| |editor1-last = Bauckham | |||

| |editor1-first = Richard | |||

| |editor2-last = Mosser | |||

| |editor2-first = Carl | |||

| |title = The Gospel of John and Christian Theology | |||

| |publisher = Eerdmans | |||

| |year = 2008 | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-8028-2717-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| | title = The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple: Narrative, History, and Theology in the Gospel of John | |||

| | last = Bauckham | first = Richard | |||

| | publisher = Baker | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-8010-3485-5 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QQzjDM_L7-oC | |||

| | date = 2007 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| | title = Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology | |||

| | last = Bauckham | first = Richard | |||

| | publisher = Baker Academic | |||

| | location = Grand Rapids | |||

| | year = 2015a | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-4412-2708-9 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xpIQBgAAQBAJ | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite book | |||

| |last1 = Bauckham | |||

| |first1 = Richard | |||

| |chapter = Sacraments and the Gospel of John | |||

| |chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=rgkWCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA83 | |||

| |editor1-last = Boersma | |||

| |editor1-first = Hans | |||

| |editor2-last = Levering | |||

| |editor2-first = Matthew | |||

| |title = The Oxford Handbook of Sacramental Theology | |||

| |publisher = Oxford University Press | |||

| |year = 2015b | |||

| |isbn = 978-0-19-163418-5 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book |editor1-last=Black |editor1-first=C. Clifton |editor2-last=Smith |editor2-first=D. Moody |editor3-last=Spivey |editor3-first=Robert A. |year=2019 |orig-date=1969 |title=Anatomy of the New Testament |chapter=John: The Gospel of Jesus' Glory |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3MSHDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA129 |location=] |publisher=] |edition=8th |pages=129–156 |doi=10.2307/j.ctvcb5b9q.15 |isbn=978-1-5064-5711-6 |s2cid=242455133 |oclc=1082543536}} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| | title=The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel | |||

| | last = Blomberg | first = Craig | |||

| | author-link = Craig Blomberg | |||

| | publisher = InterVarsity Press | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-8308-3871-4 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yvcktkwnjxEC | |||

| | date = 2011 | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=Jesus the Purifier: John's Gospel and the Fourth Quest for the Historical Jesus |last=Blomberg |first=Craig L. |publisher=Baker Academic |year=2023 |isbn=978-1-4934-3996-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UcB8EAAAQBAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | |||

| | title = John 4: 4–42: Defining A Modus Vivendi Between Jews and the Samaritans | |||

| | last = Bourgel | first = Jonathan | |||

| | journal = Journal of Theological Studies | |||

| | year = 2018 | |||

| | volume=69 | |||

| | issue=1 | |||

| | pages=39–65|url=https://www.academia.edu/37029909 | |||

| | doi = 10.1093/jts/flx215 }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | |||

| | title = The Gospel According to John, Volume 1 | |||

| | last = Brown | first = Raymond E. | |||

| | author-link = Raymond E. Brown | |||

| | year = 1966 | |||

| | publisher = Doubleday | |||

| | series = Anchor Bible series | |||

| | volume = 29 | |||