| Revision as of 17:13, 29 April 2007 editWikiEditor2004 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users51,646 edits revert sockpuppet← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:38, 18 January 2025 edit undo81.2.123.64 (talk) rv test(?)Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Hungarian traveller and writer}} | |||

| {{Copyedit|date=January 2007}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| | name = Maurice Benyovszky | |||

| | image = File:Maurice Benyovszky engraving (crop).png | |||

| | caption = Portrait of Benyovszky | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1746|9|20|df=yes}} | |||

| | birth_place = Verbó, ]<br />(present-day ], ]) | |||

| | death_date = 23 or 24 May 1786 (aged 39) | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | citizenship = ] | |||

| | father = Sámuel Benyovszky | |||

| | mother = Anna Rozália Révay | |||

| | children = Samuel, Charles, Roza and Zsofia | |||

| | awards = ] | |||

| }} | |||

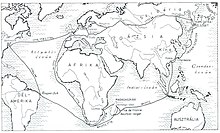

| ] | |||

| '''Count Maurice Benyovszky de Benyó et Urbanó''' ({{langx|hu|Benyovszky Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin Ágost}}; {{langx|pl|Maurycy Beniowski}}; {{langx|sk|Móric Beňovský}}; 20 September 1746 – 24 May 1786)<ref>Most biographies base themselves on Benyovszky’s editor Wm. Nicholson in citing 23 May as the date of death; however, French sources documented by Prosper Cultru cite 24 May – see: Prosper Cultru: ''Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky''. Paris (1906)</ref> was a military officer, adventurer, and writer from the ], who described himself as both a Hungarian and a Pole.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=1,3,53,381}} and Vol.2 {{rp|page=392}}</ref> He is considered a national hero in Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. | |||

| Benyovszky was born and raised in Verbó, ] (present-day ], ]). In 1769, while fighting for the Polish armies under the ], he was captured by the Russians and exiled to ]. He subsequently escaped and returned to Europe via ] and ], arriving in France. In 1773, Benyovszky reached agreement with the French government to establish a trading post on ]. Facing significant problems with the climate, the terrain, and the native ], he abandoned the trading post in 1776. | |||

| '''Moric Benovsky''' (born ] as '''Móritz Benyovszky''' - died ], ]) was a ] noble in the ], adventurer, globetrotter, explorer, colonizer, writer, chess player, the King of ], a French colonel, Polish military commander, and Austrian soldier. | |||

| Benyovszky then returned to Europe, joined the Austrian Army and fought in the ]. After a failed venture in Fiume (present-day ]), he travelled to America and obtained financial backing for a second voyage to Madagascar. The ] sent a small armed force to close down his operation, and Benyovszky was killed in May 1786. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1790, Benyovszky's posthumous and largely fictitious account of his adventures, entitled ''Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky, Volume 1'' and ''Volume 2'' was published to great success. | |||

| ==Variations on his name== | |||

| Slovak: (Matúš) '''Móric August Beňovský/Beňowský'''<br> | |||

| Polish: '''Maurycy August Beniowski'''<br> | |||

| Hungarian: '''Benyovszky Móric'''<br> | |||

| French: '''Maurice Auguste de Benyowsky/-ski'''<br> | |||

| English: (Matthew) '''Maurice Benyowsky/Benovsky'''<br> | |||

| German: '''Moritz Benjowsky/-wski/Benyowski'''<br> | |||

| Latin: '''Mauritius Auguste de Benovensis'''. | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| ==Nationality, origin of the family== | |||

| Benyovszky's autobiographical ''Memoirs'' of 1790 makes many claims about his life. Critics from 1790 onwards have shown that many of these are either false or are highly questionable.<ref name="auto">J.G.Meusel: Vermischte Nachrichten. Erlangen, (1816) {{rp|page=112–113}}</ref><ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=225–229}}</ref><ref name="auto1">Journal Encyclopédique, Vol.71, Part 2 (i) Paris (February 1791) {{rp|page=451}}</ref><ref>L.L.K: Mauritius Augustus Benyowszky. In: Notes and Queries, Series 8, Vols.6 and 7. London (1895)</ref><ref>] (ed): Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky, &c London (1893) {{rp|page=22–52}}</ref><ref>Vilmos Voigt: Maurice Benyovszky and his "Madagascar Protocolle" (1772–1776). In: Hungarian Studies, Vol.21, Part 1, (2007) {{rp|page=86–124}}</ref> Not the least is Benyovszky's opening statement that he was born in 1741, rather than 1746 – a birth-date which allowed him to claim having fought in the ] with the rank of lieutenant and having studied navigation.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=1–3}}</ref> The following biographical account includes only those facts which are (or could yet be) corroborated by other sources. It should also be noted here that, although Benyovszky freely used the titles "Baron" and "Count" for himself throughout his ''Memoirs'' and in correspondence up to 1776, he was never a "Baron" (his mother was the daughter of one) and he only became a "Count" in 1778. | |||

| Three peoples claim Beňovský as one of their own: Slovaks, Hungarians, and Poles. Beňovský was a nobleman of the Kingdom of Hungary. His father was Samuel Benyovszky. His mother, Rozália Révay, was the widow of a general and came from the ] family. The Benyovszky family has a long history. The ancestors of the Benyovszky family left Hungary to Poland, when the king was ], because they were the relatives of Felicián Zach, a supporter of ]. In 1396, Benjamin and Urbán returned to Hungary and they fought at ]. Because of their deeds, ] gave them lands at the ], and they became counts. Benjamin was the ancestor of the Benyowszky, and Urban of the Urbanovszky family. George Benyovszky lived in the XVI. century. He had three children: Gabor, Adam and Burian. Burian's son name was Michael, whose son was Samuel, who later become a general in the Austrian army and was father of Móric Beňovský. | |||

| ===Early years=== | |||

| As a young man Beňovský left Hungary to join the Polish Confederation of Bar fighting for freedom against the Russian Empress ]. He became a close associate of his Polish compatriots. Until his death Poles were his ''brothers-in-arms''. In many occasions he also declared himself a Pole. However, as many nobles of the 18th century, Beňovský was a cosmopolitan in the best tradition, serving different great powers and mastering numerous languages. | |||

| ] | |||

| Maurice Benyovszky was born on 20 September 1746 in the town of Verbó (present-day ] near ], Slovakia).<ref>Drummond, Andrew (2017): The Intriguing Life and Ignominious Death of Maurice Benyovszky (2017) {{rp|page=25}}</ref> He was baptised under the Latin names '''Mattheus Mauritius Michal Franciscus Seraphinus''' (Hungarian: ''Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin''). The additional name Augustus (''Ágost'') may also have been given, but this is not clear on his baptismal record.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939F-B3SW-GB?i=36&wc=9P34-MNB%3A107654301%2C111658101%2C111886801%2C148407701%3Fcc%3D1554443&cc=1554443|title=FamilySearch.org|website=] |accessdate=18 December 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Biography == | |||

| Maurice was the son of Sámuel Benyovszky, who came from ] in the ] (today partially ] region, in present-day ]) and is said to have served as a colonel in the ] of the Austrian Army.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.geni.com/people/Colonel-Samuel-Benyovszky-Nob/6000000017263789870|title = Colonel Samuel Benyovszky, Nob| date=28 January 1703 }}</ref> His mother, Rozália Révay, was the daughter of a baron from the noble Hungarian ]; she was the great-granddaughter of ], and the daughter of Count Boldizsár Révay de Szklabina. When she married Sámuel Benyovszky, she was the widow of an army general (Josef Pestvarmegyey, d.1743).<ref name="Maurice Count de Benyovszky">{{cite web|url=https://www.geni.com/people/Maurice-Count-de-Benyovszky/6000000016179811762|title=Maurice Count de Benyovszky|website=geni_family_tree|date=20 September 1741 }}</ref> | |||

| Beňovský was born in ] near ] in present-day ] (at that time part of the Kingdom of Hungary). His career began as an officer of the ]n army in the ], because Hungary was part of the Austrian monarchy at that time. However, his religious views and attitudes towards authority resulted in his leaving the country. From this time on he was called a sailor, an adventurer, a visionary, a colonizer, an entrepreneur, and a king. | |||

| Maurice was the eldest of four children born to Sámuel and Rozália: he had one sister, Márta, and two brothers, Ferenc (1753–?) and Emánuel (1755–1799). Both brothers followed military careers. In addition, there were three step-sisters and one step-brother, born to Rozália from her previous marriage – Theresia (1735–1763), Anna (b. pre-1743), Borbála (b. 1740), and Peter (b. 1743).<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.geni.com/people/Baroness-Roz%C3%A1lia-R%C3%A9vay-de-Treboszt%C3%B3/6000000017263836827|title=Baroness Rozália Révay de Trebosztó|website=geni_family_tree|date=4 June 1719 }}</ref> | |||

| In ] he joined the ], a ] national movement against ]n intervention. He was captured by the Russians, interned in ], and later exiled in ] (]). Subsequently, he escaped from Siberia and started a discovery trip through the Northern ]. | |||

| Maurice spent his childhood in the Benyovszky mansion in Verbó and studied from 1759 to 1760 at the ] College in Szentgyörgy (present-day ]), a suburb of Pressburg (present-day ]).<ref>Beňová, Jana: K Móricovi Beňovskému sa hlásia tri národy. SME, 24 August 2006 str. 33</ref> When both his parents died in 1760, the family home and estate was the subject of litigation between the two sets of siblings.<ref>L.L.K: Mauritius Augustus Benyowszky. In: Notes and Queries, Series 8, Vol.6. London (1895){{rp|page=483}}</ref> | |||

| In ] Beňovský arrived in ] where he impressed King ]. He was offered the opportunity to act in the name of France on Madagascar. In ] Beňovský was elected by the local tribal chiefs an ''Ampansacabe'', (king) of Madagascar. In 1776 he returned to Paris where, in appreciation for his services as Commander of Madagascar, he was promoted to the rank of General, and granted the military Order of Saint Louis and a life pension by Louis XVI. In ] Beňovský came to America, where he tried to obtain support for a proposal to use Madagascar as a base in the struggle against England. He died in ] while fighting with the French on Madagascar. | |||

| His mother tongue was Hungarian. Though no birth records have survived, his name in the records of the Szentgyörgy college appeared as a Hungarian nobleman, but for unknown reasons the following year's data were re-written to Slovak with a different handwriting.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Benyovszky Magyarsága |url=https://www.benyovszky.hu/benyovszky-magyarsaga/ |access-date=2024-06-19 |language=hu}}</ref> | |||

| ===Marriage and military service=== | |||

| ===Family=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Father: '''Samuel Beňovský''', from the noble Beňovský family. At the time of Móric's birth, Samuel was an Austrian colonel. | |||

| In 1765 Benyovszky occupied his mother's property in Hrusó (present-day Hrušové) near Verbó, which had been legally inherited by one of his step-brothers-in-law. This action led his mother's family to file a criminal complaint against him, and he was called to stand trial in Nyitra (present-day ]). Before the conclusion of the trial, Benyovszky fled to ] to join his uncle, Jan Tibor Benyowski de Benyo, a Polish nobleman. {{citation needed|date=October 2017}} His flight violated a legal edict forbidding him to leave the country. {{citation needed|date=October 2017}} | |||

| He was arrested in July 1768 in Szepesszombat (present-day ]), a suburb of Poprád (present-day ]) in the house of a German butcher named Hönsch<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.geni.com/people/Anna-Susanna/6000000016179922312|title=Anna Susanna Hönsch|date=18 October 1750 }}</ref> for trying to organize a ] militia. Shortly after his arrest, Benyovszky was briefly imprisoned in the nearby ] castle. At around this time, he married the daughter of this butcher, Anna Zusanna Hönsch (1750–1826). A child, Samuel, was born to this marriage on 9 December 1768 (d. Poprad, 22 September 1772.)<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:2:3X8C-86C|title=FamilySearch.org|website=] |accessdate=18 December 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Mother: '''Rozália Beňovský''' (maiden name: Révay), whose father was the Bishop of ]. This was her second marriage. | |||

| Three other children later came from this marriage: Charles Maurice Louis Augustus (b.1774?, Madagascar?, d. 11 July 1774, Madagascar); Roza (b. 1 January 1779, Beczko, Hungary; d. 26 October 1816, Vieszka, Hungary); and Zsofia, (b. after 1779).<ref name="Maurice Count de Benyovszky"/> | |||

| Wife: '''Zuzana Beňovská''' (maiden name: Hönsch) (]-]), the daughter of a butcher. She lived in ] in ], after Móric's death, she and her daughters departed America in ] and returned to Beňovský's castle in the Slovak town of ]. Countess Beňovská died here in ]. | |||

| ===Prisoner-of-war in Siberia=== | |||

| Siblings: one sister Márta, two brothers František and Emanuel. His brother '''Francis (Ferenc) Beňovský''' (František Beňovský) was an officer and adventurer in the ] around ] and the adjutant of Major ], head of the ] of the French cavalry supervising the British ] in America in ]. He died in America in ]. | |||

| This period of Benyovszky's life has only been documented by Benyovszky himself, in his autobiographical ''Memoirs''. There exists no independent verification of his life in the period between July 1768 and September 1770.<ref>L.L.K: Mauritius Augustus Benyowszky. In: Notes and Queries, Series 8, Vol.6. London (1895){{rp|page=4–5}}</ref> | |||

| In July 1768, Benyovszky travelled to Poland<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=3ff}}</ref> to join the patriotic forces of the ], who had organised resistance in the ] (Konfederacja Barska), a movement in rebellion against Polish king ], lately installed by Russia. In April 1769, he was captured by the Russian forces near ] in ], imprisoned in the town of ], before being transferred to ] in July, and finally to ] in September.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=34–38}}</ref> An escape attempt from Kazan brought him to ] in November, where he was recaptured and sent to the far east of ] as a prisoner.<ref>C.D and J.P. Ebeling: Neuere Geschichte der See- und Land-Reisen, Vol.IV. Begebenheiten und Reisen des Grafen Moritz August von Benjowsky wie auch einem Auszug aus Hippolitus Stefanows russisch geschriebenem Tagebuche. (1791) {{rp|page=284}}</ref> In the company of several other exiles and prisoners – most notably the Swede August Winbladh, and the Russian army-officers Vasilii Panov, Asaf Baturin and Ippolit Stepanov,<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=50}}</ref> all of whom played a major role in Benyovszky's life in the next two years – he reached ], at that time the administrative capital of ], in September 1770.<ref>C.D and J.P. Ebeling: Neuere Geschichte der See- und Land-Reisen, Vol.IV. Begebenheiten und Reisen des Grafen Moritz August von Benjowsky wie auch einem Auszug aus Hippolitus Stefanows russisch geschriebenem Tagebuche. (1791) {{rp|page=284}}</ref> | |||

| Thanks to Benjamin Franklin's help, Beňovský's descendants kept the spirit of cosmopolitanism and can be found all across Europe, as well as in the United States. | |||

| ===Escape from Kamchatka=== | |||

| ==Important dates == | |||

| Over the next few months, Benyovszky and Stepanov, along with other exiles and disaffected residents of Kamchatka, organised an escape. From the list of those<ref>V.I.Stein, Samozvannoi imperator Madagaskarskii. (M.A.Ben’ëvskii).In: Istoricheskii Vestnik No.7. St Petersburg (1908){{rp|page=605}}</ref> who participated in the escape (70 men, women, and children), it is evident that the majority were not prisoners or exiles of any sort, but just ordinary working people of Kamchatka. At the start of May, an armed uprising by the group overcame the garrison of ], during which the commander, Grigorii Nilov, was killed.<ref>Ivan Ryumin: Zapiski Kantselyarista Ryumina o priklyutsheniyach' ego s' Beniovskim. In: Siberian Archive. St. Petersburg (1822) {{rp|page=7}}</ref> The supply ship ''St Peter and St Paul'', which had been overwintering in Kamchatka, was seized and loaded with furs and provisions. On 23 May (]: 12 May), the ship set sail from the mouth of the Bolsha River, and headed southwards.<ref>C.D and J.P. Ebeling: Neuere Geschichte der See- und Land-Reisen, Vol.IV. Begebenheiten und Reisen des Grafen Moritz August von Benjowsky wie auch einem Auszug aus Hippolitus Stefanows russisch geschriebenem Tagebuche. (1791) {{rp|page=287}}</ref> | |||

| ;'''September 9, 1746''' : Beňovský is born in Vrbové near Trnava in Slovakia. Slovakia was part of the Kingdom of Hungary at that time, which in turn was part of the ]. | |||

| ;'''1746 – 1759''' : Beňovský spends his childhood in Vrbové. | |||

| ;'''1759 – 1760''' : Beňovský studies at the ] College in ], a suburb of ]. | |||

| ; '''1760''' : His mother dies, her property is inherited by her daughters from her first marriage, and Beňovský has to care for his brothers and sister. | |||

| ; '''c.1762''' : He shortly enters the army as an officer in the ] (1755 – 1763), then escapes and stays in the ]. | |||

| ; '''1764''' : He is accused of deserting and of ] (he had a rebellious attitude in matters of ] religion) and must participate in a tribunal. | |||

| ; '''1765''' : He captures his mother's (see 1760) property in Hrušové near Vrbové, previously seized by one of his brothers-in-law. He is accused for this and must participate in a tribunal in ]. Before the trial ends (1766?), he flees to Poland, by which he violates the order of queen Maria Theresa forbidding him to leave the country. | |||

| ; '''1767 – 68''' : He stays in those Spiš towns that Hungary had pawned to Poland in 1412. | |||

| ; '''1768 (beginning of)''' : For unknown reasons, Beňovský flees to Poland and enters into contact with ] (''Konfederacja Barska'') in Poland, which was rebelling against the Polish king ] installed by Russia. | |||

| ; '''1768 (July)''' : He is arrested in ] in the house of the German butcher ] (whose daughter will become his wife – see Family), because he had tried to organize a military unit for ]. In the same month he is imprisoned in the Lubovňa Castle (part of the pawned territories). | |||

| ; '''1769 - 1770''' : He joins the ] at ] (Konfederacja Barska) to fight together with ] for the independence of Poland from the Russian rule in the ]. He is captured and interned in a camp at ]. Taking advantage of local rebellions (according to some sources the rebellion was incited by Beňovský), he flees from there to ], where he tries to board a Dutch ship; the captain of the ship delivers him to the Russian police. | |||

| ; '''1770 - 1771''' : This time, the Russians send him into exile 8,000 km further east to eastern ] (]). There he is one of the few educated people, so the local governor asks him to teach his daughter to play the piano. She falls in love with him. In May 1771 Beňovský organizes a revolt of mainly ] prisoners, during which the rebels, under his leadership, capture weapons, money and a Russian battleship. Beňovský's girl is killed in ambush by a flying bullet. Beňovský then commandeers the captured battleship and on May 23 sets out for a discovery trip through the Northern Pacific (well before ] and ]) along the ], ], ], and Formosa (]), until the rebels finally arrive in ] in July 1771. In his ''Voyage to the Pacific Ocean'' (London, 1785), Capt. ] will describe meeting with ], a mutineer left by Beňovský on ] in the Aleutian Islands. That indirectly confirms that Beňovsky was in Alaska at this time. | |||

| ; '''1771 – 1773''' : In ], he enters into contact with France. The Kamchatka rebels sell their original ship and sail to France on another. On their way (around the ]) they also visit the huge island of ] off the African coast, then still independent and ruled by countless native chieftains. Finally in July 1772, he and most of the Kamchatka rebels arrive in France, where he is joined by his wife and learns about his promotion to General of the Polish Confederation, as well as his growing international fame. He suggests to King ] that he could establish a French colony on Formosa (Taiwan) or Madagascar. The king appoints him as Governor of Madagascar, gives him the title of count and a few promises, and charges him with leading a French military and trade mission to the island of Madagascar (see 1774);1774 (February): Beňovský, 21 officers, and 237 volunteers land at Madagascar. | |||

| ; '''1774 – 1775 First expedition to Madagascar''' : In Madagascar, he starts to build the town of ], a kind of base, through which France could enter into trade relations with Madagascar. He begins to build roads, settlements and to dry up swamps. Louisbourg was at the ] (Antongil Bay) and included a hospital/quarantine on Nosy Mangabe. Besides building the French presence and geographically exploring the island, Beňovský is unifying tribes there (see 1776). From the beginning, he is in conflict with the governors of the French colonies ] and ], who are his superiors and are sending negative reports on his activities to Paris, hindering his projects and causing the French Maritime Ministry to send a committee, which then finds deficiencies in Beňovský's performance. The main reason for this is that the colonisation did not bring the immediate profits expected by the French government. | |||

| ; '''1776''' : On ], the natives of Madagascar elect him King / Emperor (Ampansacabé) of Madagascar on the ] plane. Among other things, Beňovský introduces Latin script for the Madagascar language. (In the history of Madagascar, the King ] (1786-1810) is mentioned as the national unifier—in fact he built upon the efforts of the Ampansacabe Beňovský.) In general, however, Beňovský's mission largely fails (also due to illnesses caught by his men – their number will reduce to 63 in 1778) and Paris ignores his requirements. At the end of the year, Beňovský leaves the island and goes to France. | |||

| ; '''1776''' : Back in France, he tries to make sure that the amounts he had invested in Madagascar are paid to him, and he presents new proposals for the colonization of the island. He is promoted to the rank of general, and is granted the military ] and a life pension by ]. | |||

| ; '''1777''' : Still in Paris, he becomes a close friend of ] (American envoy in France) and ]. Franklin becomes like an uncle to Beňovský's two daughters. Franklin and Beňovský regularly play chess, often joined by Count Pułaski. Franklin later supported Beňovský in trying to organize an American expedition to Madagascar (see 1784). In the same year, Pułaski goes to America with Benjamin Franklin's letter of recommendation and presents to the Continental Congress a proposal from Beňovský to use Madagascar as a base in the American struggle against England. The project is not approved, because the Continental Congress does not want to risk alienating France. Also in 1777, Beňovský turns to the Austrian royal court. He petitions the Austrian empress Maria Theresa, offers his services and experience acquired abroad for the development of the commerce of his native country, and asks her pardon and permission to return home (see 1765). The royal court in Vienna changes its attitude towards Beňovský (because he now is in service of France, whose queen is member of the same — Habsburg — dynasty as that in Vienna). Amnesty is granted to him on October 17. | |||

| ; '''Late 1777/ early 1778''' : He returns to Hungary and writes a letter to the French Maritime and Colonial Ministry from his castle in Beckovská Vieska near ]. | |||

| ; '''1778''' : France grants him the title of brigadier with annual payments of 4,000 pounds, but all his proposals are rejected by the French court. On April 3 he receives a letter by Maria Theresa promoting him to the rank of count. However, his project for maritime trade from historic Hungary and for the establishment of a trade route from ] to ] (i.e., the Mediterranean) is refused by the Austrian royal court. In addition he enters the army and fights in the war between Austria and Prussia (1778-1779) in ]. | |||

| ; '''1779 First expedition to America''' : Beňovský follows Pułaski to America and offers his services in the American Revolution in person and in a letter to the Continental Congress. He is approved to report to General Pułaski at the siege of ], where Pułaski dies in his friend's arms. Without Pułaski's support, Beňovský has no choice but to return to Europe. | |||

| ; '''1780''' : In Austria, he presents another project aiming at promoting the maritime trade, but again it is rejected. | |||

| ; '''1781 - 1782 Second expedition to America''' : In 1782 Beňovský visits Philadelphia with letters of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, offering in a letter to General ] through General ] to serve in person the American Revolution and the USA, "of which he is desirous to become a citizen"; his offer is respectfully declined. A month later, through the French Minister to the United States, he submits a plan to General Washington proposing to raise in Germany a body of troops consisting of three legionary corps of cavalry, infantry, grenadiers, chasseurs and artillery, the whole amounting to 3,383 effective men, and after their transport to America they would be subject to the order of the United States and take the oaths of fidelity and allegiance. The project is favorably evaluated. Beňovský meets George and Mary Washington in their headquarters in Newborough (]). Following this discussion with Washington, Beňovský rewrites his proposal and presents it to the Continental Congress on May 6. However, the proposal is rejected by Congress following a reconciliatory change in British attitude under the new British cabinet. Beňovský writes a farewell letter to Washington and embarks on the Friendship for Europe. He stops en route in ] (now ]) to visit his brother, ], stationed there with a French army unit. | |||

| ; '''1783''' : He returns to Hungary, where he visits his castle at Beckovská Vieska and receives a privilege from the Emperor ], under which he is under special protection of the king and is authorized to found an Austrian colony on Madagascar, of which Beňovský will be the governor under the Austrian flag. However this project is not realized, because the royal court does not provide money for it. | |||

| ; '''1783''' : After failing to gain recognition in France, Austria, and the US, he turns to Great Britain, where he asks the British government to grant him an expedition to Madagascar. He gives to ], a member of the ] and descendant of the famous ], his memoirs, written in French, describing and exaggerating all his past journeys. In the same year Magellan translates it into English under the title: ''Memoirs and Travels''; the memoir will be published in 1790 in the UK. The manuscript comprises four volumes in French and Beňovský appended a signature to each of them in witness of his responsibility for their contents. The manuscript was deposited in the ] Library by the owners subsequent to their publication and are still kept in the manuscript division of the ]. The memoir would shortly be published in German (Berlin, 1790; Vienna, 1816), French (Paris, 1791), Dutch (Haarlem, 1791), Swedish (Stockholm, 1791), Polish (Warsaw, 1797), Slovak (Bratislava, 1808), and Hungarian (1888) and would become a worldwide bestseller. In the same year, with Benjamin Franklin's and J.H. Magellan's assistance, Beňovský enters into contact with the ] businessmen ] and ], who found an American-British company for trade with Madagascar. | |||

| ; '''1784 Third expedition to America''' : On March 24, Beňovský appoints J.H. Magellan ] for the State of Madagascar and authorizes him to act as representative of all economic and political affairs of the island. He leaves Baltimore for Madagascar on board the 5CC-ton vessel ''Intrepid'' provided by Messonier and Zollikofer. During the voyage the ship is blown off course and is delayed for repairs along the coast of ]. | |||

| ; '''1785 - 1786 Second expedition to Madagascar''' : In Madagascar Beňovský initiates a rebellion of the natives (who have remained loyal to him) and finally captures the French trade settlement ]. He starts building the capital of his empire, the trade settlement ''Mauritania'' (named after his himself — Maurice) at the easternmost point of the island, Cape East. In the contract with his Anglo-American associates, lots are guaranteed for all of them in the city. From Mauritania, he trades with ] and Baltimore. The main trade is in slaves. | |||

| ; '''1786''' : The French Maritime Ministry, outraged by Beňovský's cooperation with the US and by the capture of Foulpointe, sends an unexpected expedition from the ] colony to stop Beňovský. The expedition manages a surprise attack on May 23, 1786. Benovsky fights bravely, but dies from a bullet wound to his chest. He is buried at the village of Mauritania by his former lieutenant ], together with two Russian fugitives who had accompanied him from Kamchatka. | |||

| Benyovszky's ''Memoirs'' state that the route taken by the ship, having rounded the southernmost point of Kamchatka, was generally north and eastwards, taking in ], the ], ], and the ].<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=301–317}}</ref> However, in the time available (four weeks according to Benyovszky's own account), this 6000-mile itinerary is barely credible for a leaky ship and inexperienced crew. Such a route is completely absent from three other separate accounts of the voyage (by Ippolit Stepanov,<ref>C.D and J.P. Ebeling: Neuere Geschichte der See- und Land-Reisen, Vol.IV. Begebenheiten und Reisen des Grafen Moritz August von Benjowsky wie auch einem Auszug aus Hippolitus Stefanows russisch geschriebenem Tagebuche. (1791) {{rp|page=283–292}}</ref> Ivan Ryumin,<ref>Ivan Ryumin: Zapiski Kantselyarista Ryumina o priklyutsheniyach' ego s' Beniovskim. In: Siberian Archive. St. Petersburg (1822)</ref> and Gerasim Izmailov<ref>The Three Voyages of Captain James Cook (ed. James King), Vol.2 (1821) {{rp|page=458}}</ref>). Additionally, some of the events described by Benyovszky are so implausible that the entire voyage in this area must be considered a fiction.<ref>L.L.K: Mauritius Augustus Benyowszky. In: Notes and Queries, Series 8, Vol.7. London (1895){{rp|page=243}}</ref> | |||

| ==Importance == | |||

| Beňovský was a typical representative of the period of the ], the development of transport and trade, and the exploration of unknown regions. He was: | |||

| ] | |||

| * the first European sailor in the North ] region — he examined the western coast of Alaska between the mouth of the ] and ] rivers, sailing along to ] (]). His voyage to ] was the first known voyage from the northeast to the southeast shores of Asia. | |||

| * the first explorer of ]. | |||

| * a significant explorer of ] and first king of a unified Madagascar. | |||

| * the first Slovak author of a worldwide bestseller. | |||

| * the first Slovak to intervene in the development of many countries (Poland, USA, France, Austria, and Madagascar). | |||

| The ship landed at the island of ] in the ] chain, and stayed there between 29 May and 9 June to bake bread and take stock of their supplies and cargo. During this time, the sailor ] who was judged to be organising a mutiny and two other Kamchatkans were left on the island when the ship finally sailed southwards.<ref>Ivan Ryumin: Zapiski Kantselyarista Ryumina o priklyutsheniyach' ego s' Beniovskim. In: Siberian Archive. St. Petersburg (1822) {{rp|page=12–13}}</ref> Izmailov subsequently carved out a career as an explorer and trader in the Aleutians and the Alaskan coast, providing information to Captain ] in the summer of 1778.<ref>The Three Voyages of Captain James Cook (ed. James King), Vol.2 (1821) {{rp|page=455–463}}</ref> | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| Besides being the author of a bestseller at the meeting of the of ] and 19th centuries, Beňovský became a rich source of inspiration for many writers, poets, and composers. The opera ''Benyowsky and the exiles of Kamchatka''m by ], was presented in Paris in ]. The US premiere of the play ''Count Benyowsky — The Conspiracy of Kamchatka'', a tragi-comedy in five acts by the German playwright ], took place in Baltimore, along with the first performance of the US national anthem, the ], on October 19, ]. The second of eight operas by the Austrian composer ] (1821-1883), later arranged for piano by the Hungarian composer ], is called ''Benyovszky''. '']'' is also the name of an epic poem by the Polish poet ] (]-]). In his native Slovakia, many artistic works are associated with the name of Beňovský, above all the novel ''The adventures of Móric Beňovský'' by ] (1933) and the Slovak-Hungarian TV series ''Vivat Beňovský'' from ]. | |||

| Their next known port of call was at Sakinohama on the island of ] in Japan, where they rested between 19 and 23 July,<ref>Luke Roberts: Shipwrecks and Flotsam – The Foreign World in Edo-Period Tosa. In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol.70, No.1 (2015) {{rp|page=97–102}}</ref> and in the following days at Oshima island in ]. Here the voyagers managed to trade with villagers, despite this being expressly forbidden by the Japanese authorities.<ref>Luke Roberts: Shipwrecks and Flotsam – The Foreign World in Edo-Period Tosa. In: Monumenta Nipponica, Vol.70, No.1 (2015) {{rp|page=97}}</ref> | |||

| Beňovský is considered a national hero by ], ], ], and ]ians. Beňovský's name and memory have survived in Madagascar to the present day. The island opposite ] is called the Benyowsky Island on older maps, and on the way from ] to Cape East there is a ford named Baron Passage, relating to Beňovský's first stay on the island. When Madagascar gained independence, most European names fell into disuse, but not Beňovský's. One of the main streets in the capital, ] (''Rue Benyovski''), as well as streets in several other major cities, is named after the unforgettable sovereign. | |||

| == |

===Taiwan=== | ||

| At the end of July, they landed on ] in the ] islands, where they also traded successfully. At the end of August they arrived on the island of Formosa (present-day ]), probably at Black Rock Bay, where three of the voyagers were killed during a fight with native islanders.<ref>Ian Inkster: Oriental Enlightenment – the Problematic Military Experiences and Cultural Claims of Count Maurice August comte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771. In: Taiwan Historical Research, Vol.17, No.1 (2010) {{rp|page=27–70}}</ref> | |||

| '''Memoirs of Benyowsky''' | |||

| According to a 1790 English translation of the ''Memoirs'', an eighteen-person party landed on Taiwan's eastern shores in 1771. They met a few people and asked them for food. They were taken to a village and fed rice, pork, lemons, and oranges. They were offered a few knives. While making their way back to the ship, they were hit by arrows. The party fired back and killed six attackers. Near their ship, they were ambushed again by 60 warriors. They defeated their attackers and captured five of them. Benyovszky wanted to leave but his associates insisted on staying. A larger landing party rowed ashore a day later and were met by 50 unarmed locals. The party headed to the village and slaughtered 200 locals while eleven of the party members were injured. They then left and headed north with the guidance of locals.<ref name="Benyovszky">{{cite web |last1=Cheung |first1=Han |title=Taiwan in Time: A blood-soaked 16 days in Yilan |url=https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2021/07/25/2003761408 |work=Taipei Times|access-date=24 July 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ''The Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius August Count de Benyowsky, Magnate of the Kingdom of Hungary and Poland. One of the Chiefs of the Confederation of Poland. Consisting of his Military Operations in Poland, his Exile into Kamchatka, his Escape and Voyage from that Peninsula through the Northern Pacific Ocean, Touching at Japan and Formosa, to Canton in China, with an Account of the French Settlement, he was Appointed to Form upon the Island of Madagascar. Written by Himself.'' Translation from the Original Manuscript. London-Dublin, William Nicholson. | |||

| Upon reaching a "beautiful harbor" they met Don Hieronemo Pacheco, a Spaniard who had been living among the aborigines for seven to eight years. The locals were grateful toward Benyovszky for killing the villagers, who they considered their enemies. Pacheco told Benyovszky that the western side of the island was ruled by the Chinese but the rest was independent or inhabited by aborigines. Pacheco told Benyovszky that it would take very little to conquer the island and drive out the Chinese. On the third day, Benyovszky was calling the harbor "Port Maurice" after himself. Conflict broke out again as the party was fetching fresh water and three members were killed. The party executed their remaining prisoners and slaughtered a boatful of the enemies. By the end, they had killed 1,156 and captured 60 aborigines. They were visited by a prince named Huapo who believed Benyovszky was prophesied to free them from the "Chinese yoke."<ref name="Benyovszky"/> With Benyovszky's arms, Huapo then defeated his Chinese aligned foes. Huapo gifted Benyovszky's crew with gold and other valuables to try to get them to stay but Benyovszky wanted to go so that he could see his wife and son.<ref name="Benyovszky"/> | |||

| Sources in Hungarian: | |||

| There are reasons to suspect this account of events is either exaggerated or fabricated. Benyovszky's exploits have been questioned by several experts over the years. ]'s "Orientat Enlightenment: The Problematic Military Claims of Count Maurice Auguste Conte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771" criticizes the Taiwan section specifically. The population of Taiwan given by Benyovszky's account is inconsistent with estimates of that time. The stretch of coast he visited likely only had 6,000 to 10,000 inhabitants but somehow the prince was able to gather 25,000 warriors to fight 12,000 enemies.<ref name="Benyovszky"/> Even in Father de Mailla's account of Taiwan in 1715, in which he portrayed the Chinese in a very negative manner, and spoke of the entire east being in rebellion against the west, the aborigines were still unable to put up a fighting force of more than 30 or 40 armed with arrows and javelins.{{sfn|Inkster|2010|p=35-36}} Huaco was also mentioned to have nearly 100 horsemen while having 68 to spare for the European party's use. Horses were introduced to Taiwan starting in the Dutch period but it is highly unlikely that aborigines of the northeast coast had acquired so many that they could train them for large scale warfare.<ref name="Benyovszky"/> In other 18th century accounts, it was mentioned that horses were in such scarce supply that Chinese oxen were used as substitutes.{{sfn|Inkster|2010|p=36}} | |||

| ]. ''Gróf Benyovszky Móric''. | |||

| ===Macao=== | |||

| Rónaszegi, Miklós. ''A Nagy Játszma''. | |||

| Then they sailed to the Chinese mainland, at ]. Following the coast down from there, they finally arrived at ] on 22 September 1771.<ref>The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Vol.52, London. (1772) {{rp|page=272}}</ref><ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.1 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=xx–xxi}}</ref> | |||

| Shortly after their arrival in Macao, 15 of the voyagers died, most likely from the effects of malnutrition.<ref>Ivan Ryumin: Zapiski Kantselyarista Ryumina o priklyutsheniyach' ego s' Beniovskim. In: Siberian Archive. St. Petersburg (1822) {{rp|page=46}}</ref> Benyovszky took responsibility for selling the ship and all the furs they had loaded at Kamchatka, and then negotiated with the various European trading establishments for passage back to Europe.<ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=230}}</ref> In late January 1772, two French ships took the survivors away from Macao.<ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=229–230}}</ref> Some of them (13) stopped on the island of ], others died en route (8), and the remainder (26) landed at the French port of ] in July.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=90}}</ref> | |||

| Of the Nationaliti part: | |||

| * Pallas nagy lexikon | |||

| ===First expedition to Madagascar=== | |||

| * | |||

| Benyovszky managed to get a passport to enter the mainland of France and he departed almost immediately for ], leaving his companions behind. Over the next months, he toured the ministries and salons of Paris, hoping to persuade someone to fund a trading expedition to one of the several places he claimed to have visited.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=47–49}}</ref><ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=367–373}}</ref> Eventually, he managed to convince the French Foreign Minister ] and the Navy Secretary ] to fund an expedition of Benyovszky and a large group of 'Benyovszky Volunteers', to set up a French colony on ].<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=93–102}}</ref><ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=47–59}}</ref> | |||

| This expedition arrived in Madagascar in November 1773 and were fully established there by the end of March 1774. They set up a trading-post at ] on the east coast and began to negotiate with the islanders for cattle and other supplies.<ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=237}}</ref> It does not appear to have gone well, since the explorer ] arrived there shortly afterwards to discover that the Malagasy claimed Benyovszky was at war with them: supplies were therefore hard to come by.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=97}}</ref> A ship which called in at Antongil in July 1774 reported<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=98}}</ref> that 180 of the original 237 ordinary 'Volunteers' had died, and 12 of their 22 officers, all taken by sickness. A year later, despite reinforcements, personnel numbers were still dwindling.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=79–80}}</ref> | |||

| Benyovszky's ''Memoirs'' state that a son (Charles) was born to him and his wife Anna at some point during 1773 or 1774, and that the son died of fever in July 1774, though this is not verified anywhere else.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=135}}</ref> | |||

| Despite these setbacks, over the following two years, Benyovszky sent back to Paris positive reports of his advances in Madagascar, along with requests for more funding, supplies, and personnel.<ref name="auto2">Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=114ff}}</ref><ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=60–83}}</ref> The French authorities and traders on ], meanwhile, were also writing to Paris, complaining of the problems which Benyovszky was causing for their own trade with Madagascar. In September 1776, Paris sent out two government inspectors<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=112ff}}</ref> to see what Benyovszky had achieved. Their report was damning – little remained of any of the roads, hospitals or trading-posts of which Benyovszky had boasted.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=168–175}}</ref> Benyovszky's own journal of events upon Madagascar suggests great successes against a recalcitrant people, who eventually proclaimed him to be their supreme chief and King (Ampansacabe);<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=269}}</ref> however, this sits at odds with his own reports (and those of the inspectors) of unceasing troubles and minor wars against those same people.<ref name="auto2"/><ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=84–130}}</ref> In December 1776, just after the government inspectors had departed, Benyovszky left Madagascar. Following the arrival of the inspectors' report in Paris, the few surviving 'Benyovszky Volunteers' were disbanded in May 1778 and the ] was eventually dismantled by order of the French government in June 1779.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=137}}</ref> | |||

| ===Europe and America=== | |||

| After leaving Madagascar, Benyovszky arrived back in France in April 1777. He managed to be granted a medal (]) and considerable amounts of money in back-pay, and lobbied the ministers for more money and resources for a different development plan for Madagascar.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=140}}</ref> When this plan was turned down, he then petitioned ] of Austria for a pardon (for having fled Hungary for Poland in 1768) and made his way to Hungary where he received the title of 'Count' (a title he had been misusing, along with 'Baron', for several years before).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://mek.oszk.hu/06800/06877/html/02.htm#30|title=Gróf Benyovszky Móricz életrajza II.|website=mek.oszk.hu}}</ref> In July 1778 he joined the Austrian forces fighting in the ] – in which his brother Emanuel was also fighting<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=143}}</ref> – and then in early 1780 he formed a plan to develop the port of Fiume (present-day ]) as a major trading-port for Hungary.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=143–144}}</ref> He was here until the end of 1781, when he abandoned the project, leaving behind several large debts. He then made his way to the United States and, with a recommendation from ], whom he had met in Paris, attempted to persuade ] to fund a militia under Benyovszky's leadership, to fight in the ].<ref>Patrik Kunec: The Hungarian Participants in the American War of Independence. In: Codrul Cosminului, Vol.XVI, No.1. Suceava (2010) {{rp|page=47–50}}</ref> (His brother Ferenc was also at that time in America, fighting as a mercenary against the British).<ref>Patrik Kunec: The Hungarian Participants in the American War of Independence. In: Codrul Cosminului, Vol.XVI, No.1. Suceava (2010) {{rp|page=47–48}}</ref> Washington remained unconvinced, and Benyovszky then returned to Europe, arriving in Britain in late 1783. Here he submitted a proposal to the British government for a colony on Madagascar, but was again turned down.<ref>Maurice Benyovszky: Memoirs and Travels, Vol.2 (ed. Wm Nicholson) (1790) {{rp|page=395–398}}</ref> Instead he managed to persuade the ] luminary ] to fund an independent expedition; in return, Magellan received full publishing rights over the manuscript of Benyovszky's Memoirs, and the grand title of 'European ]’ for Benyovszky's new trading company.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=147}}</ref> In September 1783, Benyovszky also acquired a document signed by ] of Austria, which gave Benyovszky Austrian protection for the exploitation and government of Madagascar.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=145–146}}</ref> | |||

| ===Second expedition to Madagascar=== | |||

| In April 1784, Benyovszky and several trading partners sailed to America, where a contract was agreed to with two ] traders, Zollichofer and Meissonier.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=148}}</ref> The deal was for monetary investment in return for a regular supply of slaves. In October of that year, the ship ''Intrepid'' sailed for Madagascar, arriving near Cap St Sebastien in north-west of the island, June 1785. Here the expedition was met with aggression from the ] people; Benyovszky and a number of others were captured and disappeared, presumed dead. The surviving members of the company sailed for ], sold the ship and dispersed.<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=150–152}}</ref> | |||

| In January 1786, however, Benyovszky was reported to be alive and operating at Angonsty (near modern-day ]). Anxious about another disruption to trade, ], the ] waited for fair winds and then sent a small military force over to Madagascar to deal with Benyovszky. On 23 or 24 May 1786, Benyovszky was ambushed and killed by these troops, and was buried on the site of his encampment.<ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=259–264}}</ref><ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=155–158}}</ref> (Most biographies cite 23 May based on the statement by Benyovszky's 1790 editor William Nicholson, but French sources documented by Prosper Cultru cite 24 May.)<ref>Prosper Cultru: Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky. Paris (1906) {{rp|page=155}}</ref> | |||

| The ] newspaper '']'', in its edition of 1 December 1787, reported that the ''famous Hungarian Baron Beniowski, who was said so many times to have died'', was at that time in ], where he had come from ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://bcul.lib.uni.lodz.pl/dlibra/publication/73094/edition/64992/content|title=Gazeta Warszawska 1787, Nr 96|date=18 December 1787|accessdate=18 December 2023|via=bcul.lib.uni.lodz.pl}}</ref> However, since there is no further report of Benyovszky being alive, this report was most likely a false rumour or misunderstanding. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| ] | |||

| Much of what Benyovszky claimed to have done in Poland, Kamchatka, Japan, Formosa, and Madagascar is questionable at best, but in any case has left no lasting traces in the history of war, exploration, or colonialism.<ref>Vilmos Voigt: Maurice Benyovszky and his "Madagascar Protocolle" (1772–1776). In: Hungarian Studies, Vol.21, Part 1, (2007) {{rp|page=120–121}}</ref> His legacy resides largely in his autobiography ('']''), which was published in two volumes in 1790 by friends of ], who was by then, as a result of the failed Malagasy venture, in serious financial difficulties. Even at the time of the first publication of the book, it was met with significant scepticism by reviewers.<ref>The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Vol.60, Pt.2. London, (1790) {{rp|page=725}}</ref><ref name="auto"/><ref>Alexis Rochon: Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. J.Trapp) (1793) {{rp|page=206–234}}</ref><ref name="auto1"/> Despite this criticism, it was a great publishing success, and has since been translated into several languages; (German 1790, 1791, 1796, 1797; Dutch 1791; French 1791; Swedish 1791; Polish 1797; Slovak 1808; and Hungarian 1888).<ref>S.Pasfield Oliver (ed): Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky London (1904) {{rp|page=xxi–xxviii}}</ref> | |||

| The Kamchatkan portion of ''Memoirs'' was adapted into a number of successful plays and operas (plays by ] 1792 and ] 1794 and Operas by ] 1800 and ] 1847) which were performed in suitable translation all over Europe and America. The Polish national bard ] published a ] about him in 1841. More recently, films and television series have been made – a Czechoslovakian-Hungarian television series in 1975 (''Vivát Benyovszky!'', director: ]), "Die unfreiwilligen Reisen des Moritz August Benjowski“ (a television series in four episodes, director: Helmut Pigge, aired by the West German ] in 1975), a documentary for Hungarian TV in 2009 (''Benyovszky Móric és a malgasok földje'', director: Zsolt Cseke), and a Hungarian film ''Benyovszky, the Rebel Count ''of 2012 (director Irina Stanciulescu).<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3387218/|title = Benyovszky, the rebel count (2015)|publisher = ]}}</ref> | |||

| In Hungary, Slovakia and Poland he is still celebrated as a significant national hero.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.msz.gov.pl/pl/aktualnosci/wiadomosci/polski__krol__madagaskaru_upamietniony|title = Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych – Portal Gov.pl}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oszk.hu/en/exhibitions/moric-benyovszky-exhibition|title=Országos Széchényi Könyvtár|website=oszk.hu}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.slovakopedia.com/m/moric-benovsky.htm|title=Count Matus Moric Benovsky – Maurice Benyowsky – Slovak Adventurer and King of Madagascar|website=slovakopedia.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nbs.sk/en/banknotes-and-coins/slovak-currency/slovak-commemorative-coins/silver-200sk-coin-commemorating-the-birth-of-benovsky|title=Silver 200 Sk coin commemorating the 250th anniversary of the birth of Moric Benovsky – www.nbs.sk|website=nbs.sk}}</ref> A Hungarian-Malagasy Friendship organisation promotes the links between Benyovszky and Madagascar, arranges conferences and other meetings, and maintains a website dedicated to the celebration of Benyovszky's life.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.benyovszky.hu/ |title=Home |website=benyovszky.hu}}</ref> | |||

| The Polish writer ] visited Madagascar in 1937, spent several months in the town of Ambinanitelo and later wrote a popular travel book describing his experiences.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fiedler |first=Arkady |title=The Madagascar I love |year=1946 |edition=first English}}</ref> In it, he gives a romanticised version of Benyovszky's career. The Hungarian writer Miklós Rónaszegi also wrote a book about him in 1955, titled The Great Game (A Nagy Játszma). | |||

| Fiedler appears to have made an effort to find out if Benyovszky was still remembered by the island's people – with mixed results. In fact his name did survive in Madagascar – in recent years, a street in the island capital ] was renamed 'Lalana Benyowski'.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.mfa.gov.pl/en/news/poland_s__king__of_madagascar_remembered |title=Poland's "king" of Madagascar remembered |access-date=25 October 2017 |archive-date=26 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171026002239/http://www.mfa.gov.pl/en/news/poland_s__king__of_madagascar_remembered |url-status=dead }}</ref> Slovakians reportedly tore down his memorial in ] built by Hungarians and replaced it with their own, aiming to ] the character.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Lóránt |first=Komjáthy |date=2017-04-01 |title=Tetten ért elszlovákosítás: Így lett Gróf Benyovszky Móricból Móric Beňovský |url=https://www.korkep.sk/cikkek/tortenelem/2017/04/01/tetten-ert-elszlovakositas-igy-lett-grof-benyovszky-moricbol-moric-benovsky/ |access-date=2024-06-19 |website=Körkép.sk |language=hu}}</ref> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *Reign of ] | |||

| == Notes/Citations == | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{Cite book | last=Benyovszky | first=Maurice | title=Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky in Siberia, Kamchatka, Japan, the Liukiu Islands and Formosa | editor-last=Oliver | editor-first=Samuel Pasfield | location=London | date=1893 }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | last=Cultru | first=Prosper | title=Un Empereur de Madagascar au 18ième Siècle: Benyowszky | location=Paris | date=1906 }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | last=Drummond| first=Andrew| title=The Intriguing Life and Ignominious Death of Maurice Benyovszky | location=New York & London| date=2017 |isbn= 978-1-4128-6543-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dF8wDwAAQBAJ}} | |||

| * {{Cite book | editor1-last=Ebeling | editor1-first=C.D. | editor2-last=Ebeling | editor2-first=J.P. | title=Neuere Geschichte der See- und Land-Reisen, Vol.IV. Begebenheiten und Reisen des Grafen Moritz August von Benjowsky wie auch einem Auszug aus Hippolitus Stefanows russisch geschriebenem Tagebuche | location=Hamburg | date=1791 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | title=Oriental Enlightenment: The problematic Military Experiences and Cultural Claims of Count de Benyowsky. | last=Inkster | first=Ian | journal=Taiwan Historical Research |volume=17 | issue=1 | pages=27–70 | location=Taipei | date=2010 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | title=Mauritius Augustus Benyowszky. | last=K | first=L L. | journal=Notes and Queries | series=Series 8 | volume=s.6 and 7 | location=London | date=1895 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | last=Roberts | first=Luke | title=Shipwrecks and Flotsam: The Foreign World in Edo-Period Tosa. | journal=Monumenta Nipponica | volume=70 | issue=1 | pages=83–122 | location=Tokyo | date=2015 | doi=10.1353/mni.2015.0005 | s2cid=162781533 }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | last=Rochon | first=Alexis | title=Voyage to Madagascar and the East Indies (trans. from French by J.Trapp) | location=London | date=1793 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal | last=Ryumin | first=Ivan | title=Zapiski Kantselyarista Ryumina o priklyutsheniyach' ego s' Beniovskim. | journal=Siberian Archive | pages=3–54 | location=St. Petersburg | date=1822 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |title=Maurice Benyovszky and his 'Madagascar Protocolle' (1772–1776). | last=Voigt | first=Vilmos | journal=Hungarian Studies | volume=21| number=1 | pages=86–124 | location=Budapest | date=2007 | doi=10.1556/HStud.21.2007.1-2.10 }} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| *http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/exhibits/benyowsky/ | |||

| * | |||

| *http://www.angelfire.com/mi4/polcrt/MABeniowski.html | |||

| * | |||

| *http://www.slovakopedia.com/m/moric-benovsky.htm | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Benyovszky, Maurice}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Benovsky, Moric}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:38, 18 January 2025

Hungarian traveller and writer

| Maurice Benyovszky | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Benyovszky Portrait of Benyovszky | |

| Born | (1746-09-20)20 September 1746 Verbó, Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Vrbové, Slovakia) |

| Died | 23 or 24 May 1786 (aged 39) Angonsty, Kingdom of Imerina |

| Citizenship | Hungarian |

| Children | Samuel, Charles, Roza and Zsofia |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Order of Saint Louis |

Count Maurice Benyovszky de Benyó et Urbanó (Hungarian: Benyovszky Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin Ágost; Polish: Maurycy Beniowski; Slovak: Móric Beňovský; 20 September 1746 – 24 May 1786) was a military officer, adventurer, and writer from the Kingdom of Hungary, who described himself as both a Hungarian and a Pole. He is considered a national hero in Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia.

Benyovszky was born and raised in Verbó, Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Vrbové, Slovakia). In 1769, while fighting for the Polish armies under the Bar Confederation, he was captured by the Russians and exiled to Kamchatka. He subsequently escaped and returned to Europe via Macau and Mauritius, arriving in France. In 1773, Benyovszky reached agreement with the French government to establish a trading post on Madagascar. Facing significant problems with the climate, the terrain, and the native Sakalava people, he abandoned the trading post in 1776.

Benyovszky then returned to Europe, joined the Austrian Army and fought in the War of the Bavarian Succession. After a failed venture in Fiume (present-day Rijeka), he travelled to America and obtained financial backing for a second voyage to Madagascar. The French governor of Mauritius sent a small armed force to close down his operation, and Benyovszky was killed in May 1786.

In 1790, Benyovszky's posthumous and largely fictitious account of his adventures, entitled Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky, Volume 1 and Volume 2 was published to great success.

Biography

Benyovszky's autobiographical Memoirs of 1790 makes many claims about his life. Critics from 1790 onwards have shown that many of these are either false or are highly questionable. Not the least is Benyovszky's opening statement that he was born in 1741, rather than 1746 – a birth-date which allowed him to claim having fought in the Seven Years' War with the rank of lieutenant and having studied navigation. The following biographical account includes only those facts which are (or could yet be) corroborated by other sources. It should also be noted here that, although Benyovszky freely used the titles "Baron" and "Count" for himself throughout his Memoirs and in correspondence up to 1776, he was never a "Baron" (his mother was the daughter of one) and he only became a "Count" in 1778.

Early years

Maurice Benyovszky was born on 20 September 1746 in the town of Verbó (present-day Vrbové near Trnava, Slovakia). He was baptised under the Latin names Mattheus Mauritius Michal Franciscus Seraphinus (Hungarian: Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin). The additional name Augustus (Ágost) may also have been given, but this is not clear on his baptismal record.

Maurice was the son of Sámuel Benyovszky, who came from Turóc County in the Kingdom of Hungary (today partially Turiec region, in present-day Slovakia) and is said to have served as a colonel in the Hussars of the Austrian Army. His mother, Rozália Révay, was the daughter of a baron from the noble Hungarian Révay family; she was the great-granddaughter of Péter Révay, and the daughter of Count Boldizsár Révay de Szklabina. When she married Sámuel Benyovszky, she was the widow of an army general (Josef Pestvarmegyey, d.1743).

Maurice was the eldest of four children born to Sámuel and Rozália: he had one sister, Márta, and two brothers, Ferenc (1753–?) and Emánuel (1755–1799). Both brothers followed military careers. In addition, there were three step-sisters and one step-brother, born to Rozália from her previous marriage – Theresia (1735–1763), Anna (b. pre-1743), Borbála (b. 1740), and Peter (b. 1743).

Maurice spent his childhood in the Benyovszky mansion in Verbó and studied from 1759 to 1760 at the Piarist College in Szentgyörgy (present-day Svätý Jur), a suburb of Pressburg (present-day Bratislava). When both his parents died in 1760, the family home and estate was the subject of litigation between the two sets of siblings.

His mother tongue was Hungarian. Though no birth records have survived, his name in the records of the Szentgyörgy college appeared as a Hungarian nobleman, but for unknown reasons the following year's data were re-written to Slovak with a different handwriting.

Marriage and military service

In 1765 Benyovszky occupied his mother's property in Hrusó (present-day Hrušové) near Verbó, which had been legally inherited by one of his step-brothers-in-law. This action led his mother's family to file a criminal complaint against him, and he was called to stand trial in Nyitra (present-day Nitra). Before the conclusion of the trial, Benyovszky fled to Poland to join his uncle, Jan Tibor Benyowski de Benyo, a Polish nobleman. His flight violated a legal edict forbidding him to leave the country.

He was arrested in July 1768 in Szepesszombat (present-day Spišská Sobota), a suburb of Poprád (present-day Poprad) in the house of a German butcher named Hönsch for trying to organize a Confederation of Bar militia. Shortly after his arrest, Benyovszky was briefly imprisoned in the nearby Stará Ľubovňa castle. At around this time, he married the daughter of this butcher, Anna Zusanna Hönsch (1750–1826). A child, Samuel, was born to this marriage on 9 December 1768 (d. Poprad, 22 September 1772.)

Three other children later came from this marriage: Charles Maurice Louis Augustus (b.1774?, Madagascar?, d. 11 July 1774, Madagascar); Roza (b. 1 January 1779, Beczko, Hungary; d. 26 October 1816, Vieszka, Hungary); and Zsofia, (b. after 1779).

Prisoner-of-war in Siberia

This period of Benyovszky's life has only been documented by Benyovszky himself, in his autobiographical Memoirs. There exists no independent verification of his life in the period between July 1768 and September 1770.

In July 1768, Benyovszky travelled to Poland to join the patriotic forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, who had organised resistance in the Confederation of Bar (Konfederacja Barska), a movement in rebellion against Polish king Stanisław August Poniatowski, lately installed by Russia. In April 1769, he was captured by the Russian forces near Ternopil in Ukraine, imprisoned in the town of Polonne, before being transferred to Kiev in July, and finally to Kazan in September. An escape attempt from Kazan brought him to St Petersburg in November, where he was recaptured and sent to the far east of Siberia as a prisoner. In the company of several other exiles and prisoners – most notably the Swede August Winbladh, and the Russian army-officers Vasilii Panov, Asaf Baturin and Ippolit Stepanov, all of whom played a major role in Benyovszky's life in the next two years – he reached Bolsheretsk, at that time the administrative capital of Kamchatka, in September 1770.

Escape from Kamchatka

Over the next few months, Benyovszky and Stepanov, along with other exiles and disaffected residents of Kamchatka, organised an escape. From the list of those who participated in the escape (70 men, women, and children), it is evident that the majority were not prisoners or exiles of any sort, but just ordinary working people of Kamchatka. At the start of May, an armed uprising by the group overcame the garrison of Bolsheretsk, during which the commander, Grigorii Nilov, was killed. The supply ship St Peter and St Paul, which had been overwintering in Kamchatka, was seized and loaded with furs and provisions. On 23 May (Old Style: 12 May), the ship set sail from the mouth of the Bolsha River, and headed southwards.

Benyovszky's Memoirs state that the route taken by the ship, having rounded the southernmost point of Kamchatka, was generally north and eastwards, taking in Bering Island, the Bering Strait, Alaska, and the Aleutian Islands. However, in the time available (four weeks according to Benyovszky's own account), this 6000-mile itinerary is barely credible for a leaky ship and inexperienced crew. Such a route is completely absent from three other separate accounts of the voyage (by Ippolit Stepanov, Ivan Ryumin, and Gerasim Izmailov). Additionally, some of the events described by Benyovszky are so implausible that the entire voyage in this area must be considered a fiction.

The ship landed at the island of Simushir in the Kuril Islands chain, and stayed there between 29 May and 9 June to bake bread and take stock of their supplies and cargo. During this time, the sailor Izmailov who was judged to be organising a mutiny and two other Kamchatkans were left on the island when the ship finally sailed southwards. Izmailov subsequently carved out a career as an explorer and trader in the Aleutians and the Alaskan coast, providing information to Captain James Cook in the summer of 1778.

Their next known port of call was at Sakinohama on the island of Shikoku in Japan, where they rested between 19 and 23 July, and in the following days at Oshima island in Awa Province. Here the voyagers managed to trade with villagers, despite this being expressly forbidden by the Japanese authorities.

Taiwan

At the end of July, they landed on Amami-Oshima in the Ryükyü islands, where they also traded successfully. At the end of August they arrived on the island of Formosa (present-day Taiwan), probably at Black Rock Bay, where three of the voyagers were killed during a fight with native islanders.

According to a 1790 English translation of the Memoirs, an eighteen-person party landed on Taiwan's eastern shores in 1771. They met a few people and asked them for food. They were taken to a village and fed rice, pork, lemons, and oranges. They were offered a few knives. While making their way back to the ship, they were hit by arrows. The party fired back and killed six attackers. Near their ship, they were ambushed again by 60 warriors. They defeated their attackers and captured five of them. Benyovszky wanted to leave but his associates insisted on staying. A larger landing party rowed ashore a day later and were met by 50 unarmed locals. The party headed to the village and slaughtered 200 locals while eleven of the party members were injured. They then left and headed north with the guidance of locals.

Upon reaching a "beautiful harbor" they met Don Hieronemo Pacheco, a Spaniard who had been living among the aborigines for seven to eight years. The locals were grateful toward Benyovszky for killing the villagers, who they considered their enemies. Pacheco told Benyovszky that the western side of the island was ruled by the Chinese but the rest was independent or inhabited by aborigines. Pacheco told Benyovszky that it would take very little to conquer the island and drive out the Chinese. On the third day, Benyovszky was calling the harbor "Port Maurice" after himself. Conflict broke out again as the party was fetching fresh water and three members were killed. The party executed their remaining prisoners and slaughtered a boatful of the enemies. By the end, they had killed 1,156 and captured 60 aborigines. They were visited by a prince named Huapo who believed Benyovszky was prophesied to free them from the "Chinese yoke." With Benyovszky's arms, Huapo then defeated his Chinese aligned foes. Huapo gifted Benyovszky's crew with gold and other valuables to try to get them to stay but Benyovszky wanted to go so that he could see his wife and son.

There are reasons to suspect this account of events is either exaggerated or fabricated. Benyovszky's exploits have been questioned by several experts over the years. Ian Inkster's "Orientat Enlightenment: The Problematic Military Claims of Count Maurice Auguste Conte de Benyowsky in Formosa during 1771" criticizes the Taiwan section specifically. The population of Taiwan given by Benyovszky's account is inconsistent with estimates of that time. The stretch of coast he visited likely only had 6,000 to 10,000 inhabitants but somehow the prince was able to gather 25,000 warriors to fight 12,000 enemies. Even in Father de Mailla's account of Taiwan in 1715, in which he portrayed the Chinese in a very negative manner, and spoke of the entire east being in rebellion against the west, the aborigines were still unable to put up a fighting force of more than 30 or 40 armed with arrows and javelins. Huaco was also mentioned to have nearly 100 horsemen while having 68 to spare for the European party's use. Horses were introduced to Taiwan starting in the Dutch period but it is highly unlikely that aborigines of the northeast coast had acquired so many that they could train them for large scale warfare. In other 18th century accounts, it was mentioned that horses were in such scarce supply that Chinese oxen were used as substitutes.

Macao

Then they sailed to the Chinese mainland, at Dongshan Island. Following the coast down from there, they finally arrived at Macao on 22 September 1771.

Shortly after their arrival in Macao, 15 of the voyagers died, most likely from the effects of malnutrition. Benyovszky took responsibility for selling the ship and all the furs they had loaded at Kamchatka, and then negotiated with the various European trading establishments for passage back to Europe. In late January 1772, two French ships took the survivors away from Macao. Some of them (13) stopped on the island of Mauritius, others died en route (8), and the remainder (26) landed at the French port of Lorient in July.

First expedition to Madagascar

Benyovszky managed to get a passport to enter the mainland of France and he departed almost immediately for Paris, leaving his companions behind. Over the next months, he toured the ministries and salons of Paris, hoping to persuade someone to fund a trading expedition to one of the several places he claimed to have visited. Eventually, he managed to convince the French Foreign Minister d'Aiguillon and the Navy Secretary de Boynes to fund an expedition of Benyovszky and a large group of 'Benyovszky Volunteers', to set up a French colony on Madagascar.

This expedition arrived in Madagascar in November 1773 and were fully established there by the end of March 1774. They set up a trading-post at Antongil on the east coast and began to negotiate with the islanders for cattle and other supplies. It does not appear to have gone well, since the explorer Kerguelen arrived there shortly afterwards to discover that the Malagasy claimed Benyovszky was at war with them: supplies were therefore hard to come by. A ship which called in at Antongil in July 1774 reported that 180 of the original 237 ordinary 'Volunteers' had died, and 12 of their 22 officers, all taken by sickness. A year later, despite reinforcements, personnel numbers were still dwindling.

Benyovszky's Memoirs state that a son (Charles) was born to him and his wife Anna at some point during 1773 or 1774, and that the son died of fever in July 1774, though this is not verified anywhere else.

Despite these setbacks, over the following two years, Benyovszky sent back to Paris positive reports of his advances in Madagascar, along with requests for more funding, supplies, and personnel. The French authorities and traders on Mauritius, meanwhile, were also writing to Paris, complaining of the problems which Benyovszky was causing for their own trade with Madagascar. In September 1776, Paris sent out two government inspectors to see what Benyovszky had achieved. Their report was damning – little remained of any of the roads, hospitals or trading-posts of which Benyovszky had boasted. Benyovszky's own journal of events upon Madagascar suggests great successes against a recalcitrant people, who eventually proclaimed him to be their supreme chief and King (Ampansacabe); however, this sits at odds with his own reports (and those of the inspectors) of unceasing troubles and minor wars against those same people. In December 1776, just after the government inspectors had departed, Benyovszky left Madagascar. Following the arrival of the inspectors' report in Paris, the few surviving 'Benyovszky Volunteers' were disbanded in May 1778 and the trading post was eventually dismantled by order of the French government in June 1779.

Europe and America

After leaving Madagascar, Benyovszky arrived back in France in April 1777. He managed to be granted a medal (Order of Saint Louis) and considerable amounts of money in back-pay, and lobbied the ministers for more money and resources for a different development plan for Madagascar. When this plan was turned down, he then petitioned Empress Maria Theresa of Austria for a pardon (for having fled Hungary for Poland in 1768) and made his way to Hungary where he received the title of 'Count' (a title he had been misusing, along with 'Baron', for several years before). In July 1778 he joined the Austrian forces fighting in the War of the Bavarian Succession – in which his brother Emanuel was also fighting – and then in early 1780 he formed a plan to develop the port of Fiume (present-day Rijeka) as a major trading-port for Hungary. He was here until the end of 1781, when he abandoned the project, leaving behind several large debts. He then made his way to the United States and, with a recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in Paris, attempted to persuade George Washington to fund a militia under Benyovszky's leadership, to fight in the American War of Independence. (His brother Ferenc was also at that time in America, fighting as a mercenary against the British). Washington remained unconvinced, and Benyovszky then returned to Europe, arriving in Britain in late 1783. Here he submitted a proposal to the British government for a colony on Madagascar, but was again turned down. Instead he managed to persuade the Royal Society of London luminary Jean Hyacinthe de Magellan to fund an independent expedition; in return, Magellan received full publishing rights over the manuscript of Benyovszky's Memoirs, and the grand title of 'European Plenipotentiary’ for Benyovszky's new trading company. In September 1783, Benyovszky also acquired a document signed by Emperor Joseph II of Austria, which gave Benyovszky Austrian protection for the exploitation and government of Madagascar.

Second expedition to Madagascar

In April 1784, Benyovszky and several trading partners sailed to America, where a contract was agreed to with two Baltimore traders, Zollichofer and Meissonier. The deal was for monetary investment in return for a regular supply of slaves. In October of that year, the ship Intrepid sailed for Madagascar, arriving near Cap St Sebastien in north-west of the island, June 1785. Here the expedition was met with aggression from the Sakalava people; Benyovszky and a number of others were captured and disappeared, presumed dead. The surviving members of the company sailed for Mozambique, sold the ship and dispersed.