| Revision as of 14:10, 9 October 2023 editAdam Harangozó (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,705 editsm →Breast cancer culture: added wikilinkTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:15, 14 January 2025 edit undoChicdat (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers21,428 edits Reverted 1 pending edit by 80.41.97.236 to revision 1266810123 by 209.212.196.224: you need a sourceTag: Manual revert | ||

| (262 intermediate revisions by 98 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Cancer that originates in mammary glands}} | {{Short description|Cancer that originates in mammary glands}} | ||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| {{pp-pc1}} | |||

| {{pp-pc}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=March 2024}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2021}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2021}} | ||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | {{Infobox medical condition (new) | ||

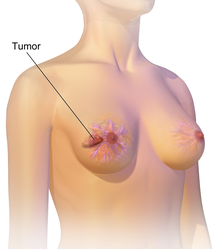

| | name |

| name = Breast cancer | ||

| | image |

| image = Breast Cancer.png | ||

| | caption |

| caption = An illustration of breast cancer | ||

| | field |

| field = ] | ||

| | symptoms |

| symptoms = A lump in a breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, fluid from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, a red scaly patch of skin on the breast<ref name=NCI2014Pt/> | ||

| | complications = | | complications = | ||

| | onset |

| onset = | ||

| | duration |

| duration = | ||

| | causes |

| causes = | ||

| | risks |

| risks = Being female, ], lack of exercise, alcohol, ] during ], ], early age at ], having children late in life or not at all, older age, prior breast cancer, family history of breast cancer, ]<ref name=NCI2014Pt /><ref name=WCR2014 /><ref name = NICHD>{{cite web |url = http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/klinefelter_syndrome.cfm |title = Klinefelter Syndrome |date = 24 May 2007 |publisher = ] |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20121127030744/http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/klinefelter_syndrome.cfm |archive-date = 27 November 2012 }}</ref> | ||

| | diagnosis |

| diagnosis = ]<ref name=NCI2014Pt /><br />], <br/>] | ||

| | differential |

| differential = | ||

| | prevention |

| prevention = | ||

| | treatment |

| treatment = Surgery, ], ], ], ]<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> | ||

| | medication |

| medication = | ||

| | prognosis |

| prognosis = ] is approximately 85% (US, UK)<ref name=SEER2014 /><ref name=UK2013Prog /> | ||

| | frequency |

| frequency = 2.2 million affected (global, 2020)<!-- prevalence --><ref name=Sung2021>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F | title = Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries | journal = CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians | volume = 71 | issue = 3 | pages = 209–249 | date = May 2021 | pmid = 33538338 | doi = 10.3322/caac.21660 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | ||

| | deaths |

| deaths = 685,000 (global, 2020)<ref name=Sung2021/> | ||

| | alt |

| alt = As seen on the image above the breast is already affected with cancer | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Definitions and symptoms --> | <!-- Definitions and symptoms --> | ||

| '''Breast cancer''' is ] that develops from ] tissue.<ref>{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast |website = NCI |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140625232947/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast |archive-date = 25 June 2014 |date = January 1980 }}</ref> Signs of breast cancer may include a ] in the breast, a change in breast shape, ] of the skin, ], fluid coming from the ], a newly inverted nipple, or a red or scaly patch of skin.<ref name=NCI2014Pt>{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/Patient/page1/AllPages |website = NCI |date = 23 May 2014 |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140705110404/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/Patient/page1/AllPages |archive-date = 5 July 2014 }}</ref> In those with ], there may be ], swollen ]s, ], or ].<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Saunders C, Jassal S |title = Breast cancer |date = 2009 |publisher = Oxford University Press |location = Oxford |isbn = 978-0-19-955869-8 |page = Chapter 13 |edition = 1. |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=as46WowY_usC&pg=PT123 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151025013217/https://books.google.com/books?id=as46WowY_usC&pg=PT123 |archive-date = 25 October 2015 }}</ref> | '''Breast cancer''' is a ] that develops from ] tissue.<ref>{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast |website = NCI |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140625232947/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast |archive-date = 25 June 2014 |date = January 1980 }}</ref> Signs of breast cancer may include a ] in the breast, a change in breast shape, ] of the skin, ], fluid coming from the ], a newly inverted nipple, or a red or scaly patch of skin.<ref name=NCI2014Pt>{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/Patient/page1/AllPages |website = NCI |date = 23 May 2014 |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140705110404/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/Patient/page1/AllPages |archive-date = 5 July 2014 }}</ref> In those with ], there may be ], swollen ]s, ], or ].<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Saunders C, Jassal S |title = Breast cancer |date = 2009 |publisher = Oxford University Press |location = Oxford |isbn = 978-0-19-955869-8 |page = Chapter 13 |edition = 1. |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=as46WowY_usC&pg=PT123 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151025013217/https://books.google.com/books?id=as46WowY_usC&pg=PT123 |archive-date = 25 October 2015 }}</ref> | ||

| <!-- Causes and diagnosis' --> | <!-- Causes and diagnosis' --> | ||

| Risk factors for developing breast cancer include ], a ], |

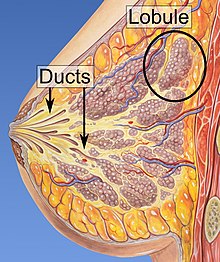

Risk factors for developing breast cancer include ], a ], alcohol consumption, ] during ], ], an early age at ], having children late in life (or not at all), older age, having a prior history of breast cancer, and a family history of breast cancer.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /><ref name="WCR2014">{{cite book |title = World Cancer Report 2014 |date = 2014 |publisher = World Health Organization |isbn = 978-92-832-0429-9 |pages = Chapter 5.2 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fakhri N, Chad MA, Lahkim M, Houari A, Dehbi H, Belmouden A, El Kadmiri N | title = Risk factors for breast cancer in women: an update review | journal = Medical Oncology | volume = 39 | issue = 12 | pages = 197 | date = September 2022 | pmid = 36071255 | doi = 10.1007/s12032-022-01804-x }}</ref> About five to ten percent of cases are the result of an inherited genetic predisposition,<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> including ] among others.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> Breast cancer most commonly develops in cells from the lining of ] and the ] that supply these ducts with milk.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> Cancers developing from the ducts are known as ], while those developing from lobules are known as ]s.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> There are more than 18 other sub-types of breast cancer.<ref name=WCR2014 /> Some, such as ], develop from ].<ref name=WCR2014 /> The diagnosis of breast cancer is confirmed by taking a ] of the concerning tissue.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> Once the diagnosis is made, further tests are carried out to determine if the cancer has spread beyond the breast and which treatments are most likely to be effective.<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> | ||

| <!-- Screening and treatments -->Breast cancer screening can be instrumental, given that the size of a breast cancer and its spread are among the most critical factors in predicting the prognosis of the disease. Breast cancers found during screening are typically smaller and less likely to have spread outside the breast.<ref>{{Cite web |last=American Cancer Society |date=9 September 2024 |title=American Cancer Society Recommendations for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer |url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html#:~:text=Women%2045%20to%2054%20should,at%20least%2010%20more%20years. |access-date=26 September 2024 |website=American Cancer Society}}</ref> A 2013 ] found that it was unclear whether ]ic screening does more harm than good, in that a large proportion of women who test positive turn out not to have the disease.<ref name="Got2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ | title = Screening for breast cancer with mammography | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2013 | issue = 6 | pages = CD001877 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23737396 | pmc = 6464778 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5 }}</ref> A 2009 review for the ] found evidence of benefit in those 40 to 70 years of age,<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors= Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan B, Nygren P, Humphrey L|title= Screening for Breast Cancer: Systematic Evidence Review Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force |date= November 2009| pmid = 20722173 |journal= U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses|location= Rockville, MD|publisher= Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality|id=Report No.: 10-05142-EF-1}}</ref> and the organization recommends screening every two years in women 50 to 74 years of age.<ref name="USPSTFScreen2016">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siu AL | title = Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | journal = Annals of Internal Medicine | volume = 164 | issue = 4 | pages = 279–96 | date = February 2016 | pmid = 26757170 | doi = 10.7326/M15-2886 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The medications ] or ] may be used in an effort to prevent breast cancer in those who are at high risk of developing it.<ref name="WCR2014" /> ] is another preventive measure in some high risk women.<ref name="WCR2014" /> In those who have been diagnosed with cancer, a number of treatments may be used, including surgery, ], ], ], and ].<ref name="NCI2014Pt" /> Types of surgery vary from ] to ].<ref name="ACSfive">{{Cite web |date = September 2013 |title = Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |publisher = ] |work = ]: an initiative of the ] |url = http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-surgeons/ |access-date = 2 January 2013 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131027085747/http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-surgeons/ |archive-date = 27 October 2013 }}</ref><ref name="NCI2014TxProf">{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/page1/AllPages |website = NCI |access-date = 29 June 2014 |date = 26 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140705110521/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/page1/AllPages |archive-date = 5 July 2014 }}</ref> ] may take place at the time of surgery or at a later date.<ref name="NCI2014TxProf" /> In those in whom the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, treatments are mostly aimed at improving quality of life and comfort.<ref name="NCI2014TxProf" /><!-- Prognosis and epidemiology--> | |||

| <!-- Screening and treatments --> | |||

| The balance of benefits versus harms of ] is controversial. A 2013 ] found that it was unclear if ] screening does more harm than good, in that a large proportion of women who test positive turn out not to have the disease.<ref name="Got2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ | title = Screening for breast cancer with mammography | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2013 | issue = 6 | pages = CD001877 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23737396 | pmc = 6464778 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5 }}</ref> A 2009 review for the ] found evidence of benefit in those 40 to 70 years of age,<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors= Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan B, Nygren P, Humphrey L|title= Screening for Breast Cancer: Systematic Evidence Review Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force |date= November 2009| pmid = 20722173 |journal= U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses|location= Rockville, MD|publisher= Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality|id=Report No.: 10-05142-EF-1}}</ref> and the organization recommends screening every two years in women 50 to 74 years of age.<ref name="USPSTFScreen2016">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siu AL | title = Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | journal = Annals of Internal Medicine | volume = 164 | issue = 4 | pages = 279–96 | date = February 2016 | pmid = 26757170 | doi = 10.7326/M15-2886 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The medications ] or ] may be used in an effort to prevent breast cancer in those who are at high risk of developing it.<ref name=WCR2014 /> ] is another preventive measure in some high risk women.<ref name=WCR2014 /> In those who have been diagnosed with cancer, a number of treatments may be used, including surgery, ], ], ], and ].<ref name=NCI2014Pt /> Types of surgery vary from ] to ].<ref name="ACSfive">{{Cite web |date = September 2013 |title = Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |publisher = ] |work = ]: an initiative of the ] |url = http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-surgeons/ |access-date = 2 January 2013 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131027085747/http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-surgeons/ |archive-date = 27 October 2013 }}</ref><ref name=NCI2014TxProf>{{cite web |title = Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/page1/AllPages |website = NCI |access-date = 29 June 2014 |date = 26 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140705110521/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/page1/AllPages |archive-date = 5 July 2014 }}</ref> ] may take place at the time of surgery or at a later date.<ref name=NCI2014TxProf /> In those in whom the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, treatments are mostly aimed at improving quality of life and comfort.<ref name=NCI2014TxProf /> | |||

| Outcomes for breast cancer vary depending on the cancer type, the ], and the person's age.<ref name=NCI2014TxProf /> The ]s in England and the United States are between 80 and 90%.<ref name=WCR2008>{{cite web |publisher = ] |year = 2008 |title = World Cancer Report |url = http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2008/wcr_2008.pdf |access-date = 26 February 2011 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110720232417/http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2008/wcr_2008.pdf |archive-date = 20 July 2011 }}</ref><ref name=SEER2014>{{cite web |title = SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer |url = http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html |website = NCI |access-date = 18 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140703030149/http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html |archive-date = 3 July 2014 }}</ref><ref name=UK2013Prog>{{cite web |title = Cancer Survival in England: Patients Diagnosed 2007–2011 and Followed up to 2012 |url = http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_333318.pdf |website = Office for National Statistics |access-date = 29 June 2014 |date = 29 October 2013 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141129124915/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_333318.pdf |archive-date = 29 November 2014 }}</ref> In developing countries, five-year survival rates are lower.<ref name=WCR2014 /> Worldwide, breast cancer is the leading type of cancer in women, accounting for 25% of all cases.<ref name="WCR2014Epi">{{cite book |title = World Cancer Report 2014 |date = 2014 |publisher = World Health Organization |isbn = 978-92-832-0429-9 |pages = Chapter 1.1 }}</ref> In 2018, it resulted in two million new cases and 627,000 deaths.<ref name=Bra2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A | title = Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries | journal = CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians | volume = 68 | issue = 6 | pages = 394–424 | date = November 2018 | pmid = 30207593 | doi = 10.3322/caac.21492 | doi-access = free}}</ref> It is more common in developed countries,<ref name=WCR2014 /> and is more than 100 times more common in women than ].<ref name=WCR2008 /><ref>{{cite web |title = Male Breast Cancer Treatment |website= ] |year = 2014 |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast/HealthProfessional |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140704182515/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast/HealthProfessional |archive-date = 4 July 2014 }}</ref> For ] individuals on ], breast cancer is 5 times more common in cisgender women than in ], and 46 times more common in ] than in cisgender men.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.breastcancer.org/news/screening-transgender-non-binary | title=Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines for Transgender People }}</ref><!-- Prevalence--> | |||

| <!-- Prognosis and epidemiology--> | |||

| Outcomes for breast cancer vary depending on the cancer type, the ], and the person's age.<ref name=NCI2014TxProf /> The ]s in England and the United States are between 80 and 90%.<ref name=WCR2008>{{cite web |publisher = ] |year = 2008 |title = World Cancer Report |url = http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2008/wcr_2008.pdf |access-date = 26 February 2011 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110720232417/http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2008/wcr_2008.pdf |archive-date = 20 July 2011 }}</ref><ref name=SEER2014>{{cite web |title = SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer |url = http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html |website = NCI |access-date = 18 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140703030149/http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html |archive-date = 3 July 2014 }}</ref><ref name=UK2013Prog>{{cite web |title = Cancer Survival in England: Patients Diagnosed 2007–2011 and Followed up to 2012 |url = http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_333318.pdf |website = Office for National Statistics |access-date = 29 June 2014 |date = 29 October 2013 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141129124915/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_333318.pdf |archive-date = 29 November 2014 }}</ref> In developing countries, five-year survival rates are lower.<ref name=WCR2014 /> Worldwide, breast cancer is the leading type of cancer in women, accounting for 25% of all cases.<ref name="WCR2014Epi">{{cite book |title = World Cancer Report 2014 |date = 2014 |publisher = World Health Organization |isbn = 978-92-832-0429-9 |pages = Chapter 1.1 }}</ref> In 2018, it resulted in 2 million new cases and 627,000 deaths.<ref name=Bra2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A | title = Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries | journal = CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians | volume = 68 | issue = 6 | pages = 394–424 | date = November 2018 | pmid = 30207593 | doi = 10.3322/caac.21492 | s2cid = 52188256 | doi-access = free}}</ref> It is more common in developed countries<ref name=WCR2014 /> and is more than 100 times more common in women than ].<ref name=WCR2008 /><ref>{{cite web |title = Male Breast Cancer Treatment |publisher = ] |year = 2014 |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast/HealthProfessional |access-date = 29 June 2014 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140704182515/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/malebreast/HealthProfessional |archive-date = 4 July 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

| == Signs and symptoms == | == Signs and symptoms == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Most people with breast cancer have no symptoms at the time of diagnosis; their tumor is detected by a breast cancer screening test.{{sfn|Hayes|Lippman|2022|loc="Evaluation of Breast Masses"}} For those who do have symptoms, a new ] in the breast is most common. Most breast lumps are not cancer, though lumps that are painless, hard, and with irregular edges are more likely to be cancerous.<ref name=ACS-SS>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/breast-cancer-signs-and-symptoms.html |accessdate=25 March 2024 |title=Breast Cancer Signs and Symptoms |publisher=American Cancer Society |date=14 January 2022}}</ref> Other symptoms include swelling or pain in the breast; dimpling, thickening, redness, or dryness of the breast skin; and pain, or inversion of the nipple.<ref name=ACS-SS/> Some may experience unusual discharge from the breasts, or swelling of the lymph nodes under the arms or along the ].<ref name=ACS-SS/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Breast cancer most commonly presents as a ] that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue. More than 80% of cases are discovered when a person detects such a lump with the fingertips.<ref name="merck">{{cite book |title=Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy |date = February 2003 |chapter=Breast Disorders: Breast Cancer |chapter-url=http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/womens_health_issues/breast_disorders/breast_cancer.html |access-date = 5 February 2008 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111002141649/http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/womens_health_issues/breast_disorders/breast_cancer.html |archive-date = 2 October 2011 |title-link = Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy}}</ref> The earliest breast cancers, however, are detected by a ].<ref name="acs cancer facts 2007" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, Jong RA, Hislop G, Chiarelli A, Minkin S, Yaffe MJ | display-authors = 6 | title = Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 356 | issue = 3 | pages = 227–36 | date = January 2007 | pmid = 17229950 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMoa062790 | s2cid = 13831558 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Lumps found in lymph nodes located in the armpits<ref name="merck" /> may also indicate breast cancer. | |||

| Some less common forms of breast cancer cause distinctive symptoms. Up to 5% of people with breast cancer have ], where cancer cells block the ]s of one breast, causing the breast to substantially swell and redden over three to six months.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/types-of-breast-cancer/inflammatory-breast-cancer.html |accessdate=28 March 2024 |title=Inflammatory Breast Cancer |publisher=American Cancer Society |date=1 March 2023}}</ref> Up to 3% of people with breast cancer have ], with ]-like red, scaly irritation on the nipple and ].<ref name=CRUK-Paget>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/types/pagets-disease-breast |accessdate=25 March 2024 |title=Paget's disease of the breast |publisher=Cancer Research UK |date=20 June 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Indications of breast cancer other than a lump may include thickening different from the other breast tissue, one breast becoming larger or lower, a nipple changing position or shape or becoming inverted, skin puckering or dimpling, a rash on or around a nipple, discharge from nipple/s, constant pain in part of the breast or armpit and swelling beneath the armpit or around the collarbone.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Watson M |title = Assessment of suspected cancer |journal = InnoAiT |volume = 1 |issue = 2 |pages = 94–107 |year = 2008 |doi = 10.1093/innovait/inn001 |s2cid = 71908359 }}</ref> Pain ("]") is an unreliable tool in determining the presence or absence of breast cancer, but may be indicative of other ] issues.<ref name="merck" /><ref name="acs cancer facts 2007">{{cite web |website=] |year = 2007 |title = Cancer Facts & Figures 2007 |url = http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf |access-date = 26 April 2007 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070410025934/http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007PWSecured.pdf |archive-date = 10 April 2007 }}</ref><ref name="eMed">{{Cite web|website=eMedicine|date=23 August 2006|title=Breast Cancer Evaluation|url=http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC3287.HTM|access-date=5 February 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080212070431/http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC3287.HTM|archive-date=12 February 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Advanced tumors can spread (metastasize) beyond the breast, most commonly to the bones, liver, lungs, and brain.{{sfn|Harbeck|Penault-Llorca|Cortes|Gnant|2019|loc="Fig. 9: Common Metastatic Sites in Breast Cancer"}} Bone metastases can cause swelling, progressive ], and weakening of the bones that leads to ].<ref name=BCRF-met>{{cite web|url=https://www.bcrf.org/blog/metastatic-breast-cancer-symptoms-treatment/ |accessdate=3 May 2024 |title=Metastatic Breast Cancer: Symptoms, Treatment, Research |date=27 February 2024 |publisher=Breast Cancer Research Foundation}}</ref> Liver metastases can cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and skin problems – ], itchy skin, or yellowing of the skin (]).<ref name=BCRF-met/> Those with lung metastases experience ], shortness of breath, and regular ]ing.<ref name=BCRF-met/> Metastases in the brain can cause persistent ], ]s, nausea, vomiting, and disruptions to the affected person's speech, vision, memory, and regular behavior.<ref name=BCRF-met/> | |||

| Another symptom complex of breast cancer is ]. This syndrome presents as skin changes resembling eczema; such as redness, discoloration or mild flaking of the nipple skin. As Paget's disease of the breast advances, symptoms may include tingling, itching, increased sensitivity, burning, and pain. There may also be discharge from the nipple. Approximately half the women diagnosed with Paget's disease of the breast also have a lump in the breast.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ashikari R, Park K, Huvos AG, Urban JA | title = Paget's disease of the breast | journal = Cancer | volume = 26 | issue = 3 | pages = 680–5 | date = September 1970 | pmid = 4318756 | doi = 10.1002/1097-0142(197009)26:3<680::aid-cncr2820260329>3.0.co;2-p | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kollmorgen DR, Varanasi JS, Edge SB, Carson WE | title = Paget's disease of the breast: a 33-year experience | journal = Journal of the American College of Surgeons | volume = 187 | issue = 2 | pages = 171–7 | date = August 1998 | pmid = 9704964 | doi = 10.1016/S1072-7515(98)00143-4 }}</ref> | |||

| == Screening == | |||

| ] is a rare (only seen in less than 5% of breast cancer diagnosis) yet aggressive form of breast cancer characterized by the swollen, red areas formed on the top of the breast. The visual effects of inflammatory breast cancer is a result of a blockage of lymph vessels by cancer cells. This type of breast cancer is seen in more commonly diagnosed in younger ages, obese women and African American women. As inflammatory breast cancer does not present as a lump there can sometimes be a delay in diagnosis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Merajver SD | title = Molecular biology of breast cancer metastasis. Inflammatory breast cancer: clinical syndrome and molecular determinants | journal = Breast Cancer Research | volume = 2 | issue = 6 | pages = 423–9 | date = 1 December 2000 | pmid = 11250736 | pmc = 138665 | doi = 10.1186/bcr89 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Breast cancer screening}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (MSC) is a rare form of the ]s that occurs exclusively in the breast.<ref name="pmid34282256">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gong P, Xia C, Yang Y, Lei W, Yang W, Yu J, Ji Y, Ren L, Ye F | title = Clinicopathologic profiling and oncologic outcomes of secretory carcinoma of the breast | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 11 | issue = 1 | pages = 14738 | date = July 2021 | pmid = 34282256 | pmc = 8289843 | doi = 10.1038/s41598-021-94351-w | bibcode = 2021NatSR..1114738G | url = }}</ref> It usually develops in adults but in a significant percentage of cases also affects children:<ref name="pmid35156343">{{cite journal | vauthors = Carretero-Barrio I, Santón A, Caniego Casas T, López Miranda E, Reguero-Callejas ME, Pérez-Mies B, Benito A, Palacios J | title = Cytological and molecular characterization of secretory breast carcinoma | journal = Diagnostic Cytopathology | volume = 50| issue = 7| pages = E174–E180| date = February 2022 | pmid = 35156343 | doi = 10.1002/dc.24945 | pmc = 9303577 | s2cid = 246813006 | url = }}</ref> MSC accounts for 80% of all childhood breast cancers.<ref name="pmid34243852">{{cite journal | vauthors = Knaus ME, Grabowksi JE | title = Pediatric Breast Masses: An Overview of the Subtypes, Workup, Imaging, and Management | journal = Advances in Pediatrics | volume = 68 | issue = | pages = 195–209 | date = August 2021 | pmid = 34243852 | doi = 10.1016/j.yapd.2021.05.006 | s2cid = 235786044 | url = }}</ref> MSC lesions are typically slow growing, painless, small ] that have invaded the tissue around their ] of origin, often spread to ] and/or ], but rarely metastasized to distant tissues.<ref name="pmid35106856">{{cite journal | vauthors = Loo SK, Yates ME, Yang S, Oesterreich S, Lee AV, Wang XS | title = Fusion-associated carcinomas of the breast: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance | journal = Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer | volume = 61 | issue = 5 | pages = 261–273 | date = May 2022 | pmid = 35106856 | pmc = 8930468 | doi = 10.1002/gcc.23029 | url = }}</ref> These tumours typically have distinctive microscopic features and tumour cells that carry a balanced ] in which part of the '']'' gene is fused to part of the '']'' gene<ref name="pmid34277491">{{cite journal | vauthors = Banerjee N, Banerjee D, Choudhary N | title = Secretory carcinoma of the breast, commonly exhibits the features of low grade, triple negative breast carcinoma- A Case report with updated review of literature | journal = Autopsy & Case Reports | volume = 11 | issue = | pages = e2020227 | date = 2021 | pmid = 34277491 | pmc = 8101654 | doi = 10.4322/acr.2020.227 | url = }}</ref> to form a ], '']''. This fusion gene encodes a ] termed ETV6-NTRK3. The NTRK3 part of ETV6-NTRK3 protein has up-regulated ] activity that stimulates two ] pathways, the ] and ]s, which promote cell proliferation and survival and thereby may contribute to the development of MSC.<ref name="pmid35156343"/> Conservative surgery, modified radical mastectomy, and radical mastectomy have been the most frequent procedures used to treat adults, while simple mastectomy, local excision with ] biopsy, and complete axillary dissection have been recommended to treat children with MSC.<ref name="pmid31119054">{{cite journal | vauthors = Li L, Wu N, Li F, Li L, Wei L, Liu J | title = Clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics of 44 patients with pure secretory breast carcinoma | journal = Cancer Biology & Medicine | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 139–146 | date = February 2019 | pmid = 31119054 | pmc = 6528460 | doi = 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0035 | url = }}</ref> In all cases, long-term, e.g. >20 years, follow-up examinations are recommended.<ref name="pmid34282256"/><ref name="pmid34277491"/> The relatively rare cases of MSC that have metastasized to distant tissues have shown little or no responses to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Three patients with metastatic disease had good partial responses to ], a drug that inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion protein.<ref name="pmid34176200">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mortensen L, Ordulu Z, Dagogo-Jack I, Bossuyt V, Winters L, Taghian A, Smith BL, Ellisen LW, Kiedrowski LA, Lennerz JK, Bardia A, Spring LM | title = Locally Recurrent Secretory Carcinoma of the Breast with NTRK3 Gene Fusion | journal = The Oncologist | volume = 26 | issue = 10 | pages = 818–824 | date = October 2021 | pmid = 34176200 | pmc = 8488779 | doi = 10.1002/onco.13880 | url = }}</ref> Because of its slow growth and low rate of metastasis to distant tissues, individuals with MSC have had 20 year survival rates of 93.16%.<ref name="pmid34282256"/> | |||

| Breast cancer screening refers to testing otherwise-healthy women for breast cancer in an attempt to diagnose breast tumors early when treatments are more successful. The most common screening test for breast cancer is low-dose ] imaging of the breast, called ].<ref name=NCI-PDQ>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-screening-pdq |accessdate=5 January 2024 |publisher=National Cancer Institute |title=Breast Cancer Screening PDQ – Patient Version |date=26 June 2023}}</ref> Each breast is pressed between two plates and imaged. Tumors can appear unusually dense within the breast, distort the shape of surrounding tissue, or cause small dense flecks called ]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/screening/mammography/mammogram-images/ |accessdate=5 January 2024 |title=Findings on a Mammogram and Mammogram Results |publisher=Susan G. Komen Foundation |date=30 November 2022}}</ref> Radiologists generally report mammogram results on a standardized scale – the six-point ] (BI-RADS) is the most common globally – where a higher number corresponds to a greater risk of a cancerous tumor.{{sfn|Nielsen|Narayan|2023|loc="Interpretation of a Mammogram"}}{{sfn|Metaxa|Healy|O'Keeffe|2019|loc="Introduction"}} | |||

| In rare cases, what initially appears as a ] (hard, movable non-cancerous lump) could in fact be a ]. Phyllodes tumours are formed within the ] (connective tissue) of the breast and contain glandular as well as stromal tissue. Phyllodes tumours are not staged in the usual sense; they are classified on the basis of their appearance under the microscope as benign, borderline or malignant.<ref name="phyllodes-tumor">{{cite web |author = answers.com |title = Oncology Encyclopedia: Cystosarcoma Phyllodes |website = ] |url = http://www.answers.com/topic/phyllodes-tumor |access-date = 10 August 2010 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100908032727/http://www.answers.com/topic/phyllodes-tumor |archive-date = 8 September 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| A mammogram also reveals breast density; dense breast tissue appears opaque on a mammogram and can obscure tumors.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/mammograms/understanding-your-mammogram-report.html |accessdate=8 January 2024 |publisher=American Cancer Society |title=Understanding Your Mammogram Report |date=14 January 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/mammograms/breast-density-and-your-mammogram-report.html |accessdate=8 January 2024 |publisher=American Cancer Society |title=Breast Density and Your Mammogram Report |date=28 March 2023}}</ref> BI-RADS categorizes breast density into four categories. Mammography can detect around 90% of breast tumors in the least dense breasts (called "fatty" breasts), but just 60% in the most dense breasts (called "extremely dense").{{sfn|Nielsen|Narayan|2023|loc="Implications of Breast Density"}} Women with particularly dense breasts can instead be screened by ], ] (MRI), or ], all of which more sensitively detect breast tumors.{{sfn|Harbeck|Penault-Llorca|Cortes|Gnant|2019|loc="Screening"}} | |||

| Malignant tumours can result in metastatic tumours – secondary tumours (originating from the primary tumour) that spread beyond the site of origination. The symptoms caused by metastatic breast cancer will depend on the location of metastasis. Common sites of metastasis include bone, liver, lung, and brain.<ref name="pmid17158753">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lacroix M | title = Significance, detection and markers of disseminated breast cancer cells | journal = Endocrine-Related Cancer | volume = 13 | issue = 4 | pages = 1033–67 | date = December 2006 | pmid = 17158753 | doi = 10.1677/ERC-06-0001 | doi-access = free }}</ref> When cancer has reached such an invasive state, it is categorized as a stage 4 cancer, cancers of this state are often fatal.<ref>{{cite news |title=Stage 4 :: The National Breast Cancer Foundation |url=https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-cancer-stage-4 |newspaper=National Breast Cancer Foundation |access-date=29 April 2019 |archive-date=1 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210201225847/https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org/breast-cancer-stage-4 |url-status=live }}</ref> Common symptoms of stage 4 cancer include unexplained weight loss, bone and joint pain, jaundice and neurological symptoms. These symptoms are called ] because they could be manifestations of many other illnesses.<ref name="nci metastatic">{{cite web |author = National Cancer Institute |date = 1 September 2004 |title = Metastatic Cancer: Questions and Answers |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Sites-Types/metastatic |access-date = 6 February 2008 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080827093333/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Sites-Types/metastatic |archive-date = 27 August 2008 |author-link = National Cancer Institute }}</ref> Rarely breast cancer can spread to exceedingly uncommon sites such as peripancreatic lymph nodes causing biliary obstruction leading to diagnostic difficulties.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Perera N, Fernando N, Perera R | title = Metastatic breast cancer spread to peripancreatic lymph nodes causing biliary obstruction | journal = The Breast Journal | volume = 26 | issue = 3 | pages = 511–13 | date = March 2020 | doi = 10.1111/tbj.13531 | pmid = 31538691 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Most symptoms of breast disorders, including most lumps, do not turn out to represent underlying breast cancer. Less than 20% of lumps, for example, are cancerous,<ref>{{cite book|title=Interpreting Signs and Symptoms|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=PcARTQwHLpIC|page=99}}|year=2007|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|isbn=978-1-58255-668-0|pages=99–}}</ref> and ]s such as ] and ] of the breast are more common causes of breast disorder symptoms.<ref name="merck breasts">{{cite web |author = Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy |date = February 2003 |title = Breast Disorders: Overview of Breast Disorders |url = http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/womens_health_issues/breast_disorders/overview_of_breast_disorders.html |access-date = 5 February 2008 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111003004918/http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/womens_health_issues/breast_disorders/overview_of_breast_disorders.html |archive-date = 3 October 2011 |author-link = Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy }}</ref> | |||

| ] showing a normal breast (left) and a breast with cancer (right)]] | |||

| == Risk factors == | |||

| {{Main|Risk factors of breast cancer}} | |||

| Regular screening mammography reduces breast cancer deaths by at least 20%.{{sfn|Loibl|Poortmans|Morrow|Denkert|2021|loc="Screening"}} Most ]s recommend annual screening mammograms for women aged 50–70.{{sfn|Hayes|Lippman|2022|loc="Screening for Breast Cancer"}} Screening also reduces breast cancer mortality in women aged 40–49, and some guidelines recommend annual screening in this age group as well.{{sfn|Hayes|Lippman|2022|loc="Screening for Breast Cancer"}}{{sfn|Rahman|Helvie|2022|loc="Table 1"}} For women at high risk for developing breast cancer, most guidelines recommend adding MRI screening to mammography, to increase the chance of detecting potentially dangerous tumors.{{sfn|Harbeck|Penault-Llorca|Cortes|Gnant|2019|loc="Screening"}} Regularly feeling one's own breasts for lumps or other abnormalities, called ], does not reduce a person's chance of dying from breast cancer.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/hp/breast-screening-pdq |accessdate=10 January 2024 |publisher=National Cancer Institute |title=Breast Cancer Screening (PDQ) - Health Professional Version |date=7 June 2023}}</ref> Clinical breast exams, where a health professional feels the breasts for abnormalities, are common;{{sfn|Menes|Coster|Coster|Shenhar-Tsarfaty|2021|loc="Abstract"}} whether they reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer is not known.<ref name=NCI-PDQ/> Regular breast cancer screening is commonplace in most wealthy nations, but remains uncommon in the world's poorer countries.{{sfn|Harbeck|Penault-Llorca|Cortes|Gnant|2019|loc="Screening"}} | |||

| Risk factors can be divided into two categories: | |||

| * ''modifiable'' risk factors (things that people can change themselves, such as consumption of alcoholic beverages), and | |||

| * ''fixed'' risk factors (things that cannot be changed, such as age and physiological sex).<ref name="Hay2013">{{cite journal|vauthors=Hayes J, Richardson A, Frampton C|date=November 2013|title=Population attributable risks for modifiable lifestyle factors and breast cancer in New Zealand women|journal=Internal Medicine Journal|volume=43|issue=11|pages=1198–204|doi=10.1111/imj.12256|pmid=23910051|s2cid=23237732}}</ref> | |||

| The primary risk factors for breast cancer are being female and older age.<ref>{{Cite book |vauthors = Reeder JG, Vogel VG |chapter = Breast Cancer Prevention |volume = 141 |pages = 149–64 |year = 2008 |pmid = 18274088 |doi = 10.1007/978-0-387-73161-2_10 |series = Cancer Treatment and Research |isbn = 978-0-387-73160-5 |title = Advances in Breast Cancer Management, Second Edition }}</ref> Other potential risk factors include genetics,<ref name="Am I at risk">{{cite web |title = Am I at risk? |url = http://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/breast-cancer-information/breast-awareness/am-i-risk/risk |publisher = Breast Cancer Care |access-date = 22 October 2013 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131025074635/http://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/breast-cancer-information/breast-awareness/am-i-risk/risk |archive-date = 25 October 2013 |date = 23 February 2018 }}</ref> lack of childbearing or lack of breastfeeding,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer | title = Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease | journal = Lancet | volume = 360 | issue = 9328 | pages = 187–95 | date = July 2002 | pmid = 12133652 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0 | s2cid = 25250519 }}</ref> higher levels of certain hormones,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yager JD, Davidson NE | title = Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 354 | issue = 3 | pages = 270–82 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16421368 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMra050776 | s2cid = 5793142 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.center4research.org/hormone-therapy-menopause/ |title = Hormone Therapy and Menopause |publisher = National Research Center for Women & Families |vauthors = Mazzucco A, Santoro E, DeSoto, M, Hong Lee J |date = February 2009 |access-date = 23 January 2018 |archive-date = 7 August 2020 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200807125221/https://www.center4research.org/hormone-therapy-menopause/ |url-status = live }}</ref> certain dietary patterns, and obesity. One study indicates that exposure to light pollution is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Haim A, Portnov BP |title=Light Pollution as new risk factor for human Breast and Prostate Cancers |date=2013 |publisher=Springer |location=Dordrecht |isbn=978-94-007-6220-6}}</ref> | |||

| Still, mammography has its disadvantages. Overall, screening mammograms miss about 1 in 8 breast cancers, they can also give ] results, causing extra anxiety and making patients overgo unnecessary additional exams, such as ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Limitations of Mammograms {{!}} How Accurate Are Mammograms? |url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/mammograms/limitations-of-mammograms.html |access-date=2024-10-28 |website=www.cancer.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| If all adults maintained the healthiest possible lifestyles, including not drinking ], maintaining a healthy ], never ], eating ], and other actions, then almost a quarter of breast cancer cases worldwide could be prevented.<ref name=":2">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhang YB, Pan XF, Chen J, Cao A, Zhang YG, Xia L, Wang J, Li H, Liu G, Pan A | display-authors = 6 | title = Combined lifestyle factors, incident cancer, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies | journal = British Journal of Cancer | volume = 122 | issue = 7 | pages = 1085–1093 | date = March 2020 | pmid = 32037402 | pmc = 7109112 | doi = 10.1038/s41416-020-0741-x }}</ref> The remaining three-quarters of breast cancer cases cannot be prevented through lifestyle changes.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| === Lifestyle === | |||

| {{See also|List of breast carcinogenic substances}} | |||

| ], including beer, wine, or liquor, cause breast cancer.]] | |||

| {{Image frame | |||

| | caption=Drinking alcohol, even at low levels, increases the risk of breast cancer<br/>{{legend|red| Additional risk from drinking<ref name="Choi"/><ref name="Bagnardi">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, Tramacere I, Islami F, Fedirko V, Scotti L, Jenab M, Turati F, Pasquali E, Pelucchi C, Galeone C, Bellocco R, Negri E, Corrao G, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C | display-authors = 6 | title = Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis | journal = British Journal of Cancer | volume = 112 | issue = 3 | pages = 580–593 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25422909 | pmc = 4453639 | doi = 10.1038/bjc.2014.579 }}</ref>}} | |||

| {{legend|pink| Original breast cancer risk ({{=}}100%)}} | |||

| | content = {{Graph:Chart|width=300|height=150 | |||

| |xAxisTitle=Maximum drinks per day | |||

| |yAxisTitle=Risk | |||

| |legend=Legend | |||

| | y1Title=Risk due to drinking | |||

| | y2Title=Baseline | |||

| |type=stackedrect | |||

| | x=0,1,2,3,4+ | |||

| | y1=0,9,13,23,60 | |||

| | y2=100,100,100,100,100 | |||

| |colors=red, pink}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ], even among very light drinkers (women drinking less than half of one alcoholic drink per day).<ref name="Choi">{{cite journal | vauthors = Choi YJ, Myung SK, Lee JH | title = Light Alcohol Drinking and Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies | journal = Cancer Research and Treatment | volume = 50 | issue = 2 | pages = 474–487 | date = April 2018 | pmid = 28546524 | pmc = 5912140 | doi = 10.4143/crt.2017.094 }}</ref> The risk is highest among heavy drinkers.<ref name="Shield">{{cite journal | vauthors = Shield KD, Soerjomataram I, Rehm J | title = Alcohol Use and Breast Cancer: A Critical Review | journal = Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research | volume = 40 | issue = 6 | pages = 1166–1181 | date = June 2016 | pmid = 27130687 | doi = 10.1111/acer.13071 | quote = All levels of evidence showed a risk relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of breast cancer, even at low levels of consumption. }}</ref> Globally, about one in 10 cases of breast cancer is caused by women drinking alcoholic beverages.<ref name="Shield" /> Drinking alcoholic beverages is among the most common modifiable risk factors.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = McDonald JA, Goyal A, Terry MB | title = Alcohol Intake and Breast Cancer Risk: Weighing the Overall Evidence | journal = Current Breast Cancer Reports | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 208–221 | date = September 2013 | pmid = 24265860 | pmc = 3832299 | doi = 10.1007/s12609-013-0114-z }}</ref> | |||

| The correlation between ] and breast cancer is anything but linear. Studies show that those who rapidly gain weight in adulthood are at higher risk than those who have been overweight since childhood. Likewise excess fat in the midsection seems to induce a higher risk than excess weight carried in the lower body. This implies that the food one eats is of greater importance than one's ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Lifestyle-related Breast Cancer Risk Factors|url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention/lifestyle-related-breast-cancer-risk-factors.html|website=www.cancer.org|access-date=18 April 2018|archive-date=27 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727075717/https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/risk-and-prevention/lifestyle-related-breast-cancer-risk-factors.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Dietary factors that may increase risk include a high-fat diet<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Blackburn GL, Wang KA | title = Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: results from the Women's Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | volume = 86 | issue = 3 | pages = s878-81 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 18265482 | doi = 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.878S | doi-access = free }}</ref> and obesity-related ] levels.<ref>BBC report {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070313141518/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/5171838.stm |date=13 March 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kaiser J | title = Cancer. Cholesterol forges link between obesity and breast cancer | journal = Science | volume = 342 | issue = 6162 | pages = 1028 | date = November 2013 | pmid = 24288308 | doi = 10.1126/science.342.6162.1028 }}</ref> Dietary iodine deficiency may also play a role.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Aceves C, Anguiano B, Delgado G | title = Is iodine a gatekeeper of the integrity of the mammary gland? | journal = Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia | volume = 10 | issue = 2 | pages = 189–96 | date = April 2005 | pmid = 16025225 | doi = 10.1007/s10911-005-5401-5 | s2cid = 16838840 }}</ref> Evidence for fiber is unclear. A 2015 review found that studies trying to link fiber intake with breast cancer produced mixed results.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mourouti N, Kontogianni MD, Papavagelis C, Panagiotakos DB | title = Diet and breast cancer: a systematic review | journal = International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition | volume = 66 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–42 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25198160 | doi = 10.3109/09637486.2014.950207 | s2cid = 207498132 }}</ref> In 2016, a tentative association between low fiber intake during adolescence and breast cancer was observed.<ref>{{cite news | vauthors = Aubrey A |date = 1 February 2016 |title = A Diet High In Fiber May Help Protect Against Breast Cancer |url = https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/02/01/464854395/a-diet-high-in-fiber-may-help-protect-against-breast-cancer |newspaper = ] |access-date = 1 February 2016 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160201114307/http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/02/01/464854395/a-diet-high-in-fiber-may-help-protect-against-breast-cancer |archive-date = 1 February 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| ] appears to increase the risk of breast cancer, with the greater the amount smoked and the earlier in life that smoking began, the higher the risk.<ref name="Smoking2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Johnson KC, Miller AB, Collishaw NE, Palmer JR, Hammond SK, Salmon AG, Cantor KP, Miller MD, Boyd NF, Millar J, Turcotte F | display-authors = 6 | title = Active smoking and secondhand smoke increase breast cancer risk: the report of the Canadian Expert Panel on Tobacco Smoke and Breast Cancer Risk (2009) | journal = Tobacco Control | volume = 20 | issue = 1 | pages = e2 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 21148114 | doi = 10.1136/tc.2010.035931 | s2cid = 448229 }}</ref> In those who are long-term smokers, the relative risk is increased 35% to 50%.<ref name="Smoking2011" /> | |||

| A lack of physical activity has been linked to about 10% of cases.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT | title = Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy | journal = Lancet | volume = 380 | issue = 9838 | pages = 219–29 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22818936 | pmc = 3645500 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 }}</ref> ] regularly for prolonged periods is associated with higher mortality from breast cancer. The risk is not negated by regular exercise, though it is lowered.<ref name="Biswas">{{cite journal | vauthors = Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, Alter DA | title = Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Annals of Internal Medicine | volume = 162 | issue = 2 | pages = 123–32 | date = January 2015 | pmid = 25599350 | doi = 10.7326/M14-1651 | s2cid = 7256176 }}</ref> | |||

| ] to treat ] is also associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence | journal = Lancet | volume = 394 | issue = 10204 | pages = 1159–1168 | date = September 2019 | pmid = 31474332 | pmc = 6891893 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31709-X | author1 = Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer }}</ref> The use of ] does not cause breast cancer for most women;<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kanadys W, Barańska A, Malm M, Błaszczuk A, Polz-Dacewicz M, Janiszewska M, Jędrych M | title = Use of Oral Contraceptives as a Potential Risk Factor for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies Up to 2010 | journal = International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | volume = 18 | issue = 9 | pages = 4638 | date = April 2021 | pmid = 33925599 | pmc = 8123798 | doi = 10.3390/ijerph18094638 | doi-access = free }}</ref> if it has an effect, it is small (on the order of 0.01% per user–year; comparable to the rate of ]<ref name=":0" />), temporary, and offset by the users' significantly reduced risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers.<ref name=":0">{{cite journal | vauthors = Chelmow D, Pearlman MD, Young A, Bozzuto L, Dayaratna S, Jeudy M, Kremer ME, Scott DM, O'Hara JS | display-authors = 6 | title = Executive Summary of the Early-Onset Breast Cancer Evidence Review Conference | journal = Obstetrics and Gynecology | volume = 135 | issue = 6 | pages = 1457–1478 | date = June 2020 | pmid = 32459439 | pmc = 7253192 | doi = 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003889 }}</ref> Among those with a family history of breast cancer, use of modern oral contraceptives does not appear to affect the risk of breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A | title = Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer | journal = Contraception | volume = 80 | issue = 4 | pages = 372–380 | date = October 2009 | pmid = 19751860 | doi = 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.04.010 }}</ref> It is less certain whether hormonal contraceptives could increase the already high rates of breast cancer in women with mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Huber D, Seitz S, Kast K, Emons G, Ortmann O | title = Use of oral contraceptives in BRCA mutation carriers and risk for ovarian and breast cancer: a systematic review | journal = Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics | volume = 301 | issue = 4 | pages = 875–884 | date = April 2020 | pmid = 32140806 | pmc = 8494665 | doi = 10.1007/s00404-020-05458-w }}</ref> | |||

| ] reduces the risk of several types of cancers, including breast cancer.<ref name=":3">{{cite journal | vauthors = Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, Taneja S, Bhandari N, Rollins N, Bahl R, Martines J | display-authors = 6 | title = Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Acta Paediatrica | volume = 104 | issue = 467 | pages = 96–113 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26172878 | pmc = 4670483 | doi = 10.1111/apa.13102 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1|title=Breastfeeding|work=]|access-date=18 November 2021|archive-date=29 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190529191644/https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/#tab=tab_1|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/faq/index.htm#benefits|title=Breastfeeding:Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)|work=U.S. Center for disease control and prevention(CDC)|date=10 August 2021|access-date=18 November 2021|archive-date=6 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190506213940/https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/faq/index.htm#benefits|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | title = Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease | journal = Lancet | volume = 360 | issue = 9328 | pages = 187–195 | date = July 2002 | pmid = 12133652 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0 | s2cid = 25250519 | author1 = Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer }}</ref> In the 1980s, the ] posited that ] increased the risk of developing breast cancer.<ref name="RUSSO_505">{{cite journal | vauthors = Russo J, Russo IH | title = Susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis. II. Pregnancy interruption as a risk factor in tumor incidence | journal = The American Journal of Pathology | volume = 100 | issue = 2 | pages = 497–512 | date = August 1980 | pmid = 6773421 | pmc = 1903536 | quote = In contrast, abortion is associated with increased risk of carcinomas of the breast. The explanation for these epidemiologic findings is not known, but the parallelism between the DMBA-induced rat mammary carcinoma model and the human situation is striking. ... Abortion would interrupt this process, leaving in the gland undifferentiated structures like those observed in the rat mammary gland, which could render the gland again susceptible to carcinogenesis. }}</ref> This hypothesis was the subject of extensive scientific inquiry, which concluded that neither ]s nor abortions are associated with a heightened risk for breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Beral V, Bull D, Doll R, Peto R, Reeves G | title = Breast cancer and abortion: collaborative reanalysis of data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 83?000 women with breast cancer from 16 countries | journal = Lancet | volume = 363 | issue = 9414 | pages = 1007–16 | date = March 2004 | pmid = 15051280 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15835-2 | s2cid = 20751083 }}</ref> | |||

| Other risk factors include ]<ref name="acs bc facts 2005-6" /> and ] disruptions related to ]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang XS, Armstrong ME, Cairns BJ, Key TJ, Travis RC | title = Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence | journal = Occupational Medicine | volume = 61 | issue = 2 | pages = 78–89 | date = March 2011 | pmid = 21355031 | pmc = 3045028 | doi = 10.1093/occmed/kqr001 }}</ref> and routine late-night eating.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Marinac CR, Nelson SH, Breen CI, Hartman SJ, Natarajan L, Pierce JP, Flatt SW, Sears DD, Patterson RE | display-authors = 6 | title = Prolonged Nightly Fasting and Breast Cancer Prognosis | journal = JAMA Oncology | volume = 2 | issue = 8 | pages = 1049–55 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 27032109 | pmc = 4982776 | doi = 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0164 }}</ref> A number of chemicals have also been linked, including ], ], and ]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Brody JG, Rudel RA, Michels KB, Moysich KB, Bernstein L, Attfield KR, Gray S | title = Environmental pollutants, diet, physical activity, body size, and breast cancer: where do we stand in research to identify opportunities for prevention? | journal = Cancer | volume = 109 | issue = 12 Suppl | pages = 2627–34 | date = June 2007 | pmid = 17503444 | doi = 10.1002/cncr.22656 | s2cid = 34880415 }}</ref> Although the radiation from ] is a low dose, it is estimated that yearly screening from 40 to 80 years of age will cause approximately 225 cases of fatal breast cancer per million women screened.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hendrick RE | title = Radiation doses and cancer risks from breast imaging studies | journal = Radiology | volume = 257 | issue = 1 | pages = 246–53 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20736332 | doi = 10.1148/radiol.10100570 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| === Genetics === | |||

| Genetics is believed to be the primary cause of 5–10% of all cases.<ref name="Gage2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gage M, Wattendorf D, Henry LR | title = Translational advances regarding hereditary breast cancer syndromes | journal = Journal of Surgical Oncology | volume = 105 | issue = 5 | pages = 444–51 | date = April 2012 | pmid = 22441895 | doi = 10.1002/jso.21856 | s2cid = 3406636 }}</ref> Women whose mother was diagnosed before 50 have an increased risk of 1.7 and those whose mother was diagnosed at age 50 or after has an increased risk of 1.4.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Colditz GA, Kaphingst KA, Hankinson SE, Rosner B | title = Family history and risk of breast cancer: nurses' health study | journal = Breast Cancer Research and Treatment | volume = 133 | issue = 3 | pages = 1097–104 | date = June 2012 | pmid = 22350789 | pmc = 3387322 | doi = 10.1007/s10549-012-1985-9 }}</ref> In those with zero, one or two affected relatives, the risk of breast cancer before the age of 80 is 7.8%, 13.3%, and 21.1% with a subsequent mortality from the disease of 2.3%, 4.2%, and 7.6% respectively.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease | journal = Lancet | volume = 358 | issue = 9291 | pages = 1389–99 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11705483 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06524-2 | author1 = Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer | s2cid = 24278814 }}</ref> In those with a first degree relative with the disease the risk of breast cancer between the age of 40 and 50 is double that of the general population.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nelson HD, Zakher B, Cantor A, Fu R, Griffin J, O'Meara ES, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, van Ravesteyn NT, Trentham-Dietz A, Mandelblatt JS, Miglioretti DL | display-authors = 6 | title = Risk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Annals of Internal Medicine | volume = 156 | issue = 9 | pages = 635–48 | date = May 2012 | pmid = 22547473 | pmc = 3561467 | doi = 10.7326/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00006 }}</ref> | |||

| In less than 5% of cases, genetics plays a more significant role by causing a ].<ref name="Genetics2010">{{cite book | vauthors = Pasche B |title = Cancer Genetics (Cancer Treatment and Research) |publisher = Springer |location = Berlin |year = 2010 |pages = 19–20 |isbn = 978-1-4419-6032-0 }}</ref> This includes those who carry the ].<ref name=Genetics2010 /> These mutations account for up to 90% of the total genetic influence with a risk of breast cancer of 60–80% in those affected.<ref name=Gage2012 /> Other significant mutations include ''p53'' (]), ''PTEN'' (]), and ''STK11'' (]), ''CHEK2'', ''ATM'', ''BRIP1'', and ''PALB2''.<ref name=Gage2012 /> In 2012, researchers said that there are four genetically distinct types of the breast cancer and that in each type, hallmark genetic changes lead to many cancers.<ref name=nyt23912>{{cite news | vauthors = Kolata G |title = Genetic Study Finds 4 Distinct Variations of Breast Cancer |url = https://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/24/health/study-finds-variations-of-breast-cancer.html |newspaper = The New York Times |date = 23 September 2012 |access-date = 23 September 2012 |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120924091105/http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/24/health/study-finds-variations-of-breast-cancer.html |archive-date = 24 September 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| Other genetic predispositions include the density of the breast tissue and hormonal levels. Women with ] are more likely to get tumours and are less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer – because the dense tissue makes tumours less visible on mammograms. Furthermore, women with naturally high estrogen and progesterone levels are also at higher risk for tumour development.<ref>{{cite web |title=CDC – What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? |url=https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/risk_factors.htm |website=www.cdc.gov |date=14 December 2018 |access-date=29 April 2019 |archive-date=13 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813064946/https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/risk_factors.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tian JM, Ran B, Zhang CL, Yan DM, Li XH | title = Estrogen and progesterone promote breast cancer cell proliferation by inducing cyclin G1 expression | journal = Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research | volume = 51 | issue = 3 | pages = 1–7 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 29513878 | pmc = 5912097 | doi = 10.1590/1414-431X20175612 | url = https://www.popline.org/node/328955 | access-date = 29 April 2019 | archive-date = 14 May 2017 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170514183905/http://www.popline.org/node/328955 }}</ref> | |||

| === Medical conditions === | |||

| Breast changes like ]<ref name="urlUnderstanding Breast Changes – National Cancer Institute">{{cite web |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/understanding-breast-changes/page6#F8 |title = Understanding Breast Changes – National Cancer Institute |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100527185336/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/understanding-breast-changes/page6 |archive-date = 27 May 2010 }}</ref> and ],<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/HealthProfessional/page6 |title = Breast Cancer Treatment |publisher = National Cancer Institute |url-status = live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150425224841/http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/breast/healthprofessional/page6 |archive-date = 25 April 2015 |date = January 1980 }}</ref><ref name="pmid18562954">{{cite journal | vauthors = Afonso N, Bouwman D | title = Lobular carcinoma in situ | journal = European Journal of Cancer Prevention | volume = 17 | issue = 4 | pages = 312–6 | date = August 2008 | pmid = 18562954 | doi = 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e5d | s2cid = 388045 }}</ref> found in benign breast conditions such as ], are correlated with an increased breast cancer risk. | |||

| ] might also increase the risk of breast cancer.<ref name="pmid23709491">{{cite journal | vauthors = Anothaisintawee T, Wiratkapun C, Lerdsitthichai P, Kasamesup V, Wongwaisayawan S, Srinakarin J, Hirunpat S, Woodtichartpreecha P, Boonlikit S, Teerawattananon Y, Thakkinstian A | display-authors = 6 | title = Risk factors of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health | volume = 25 | issue = 5 | pages = 368–87 | date = September 2013 | pmid = 23709491 | doi = 10.1177/1010539513488795 | s2cid = 206616972 }}</ref> Autoimmune diseases such as ] seem also to increase the risk for the acquisition of breast cancer.<ref name="pmid21237645">{{cite journal | vauthors = Böhm I | title = Breast cancer in lupus | journal = Breast | volume = 20 | issue = 3 | pages = 288–90 | date = June 2011 | pmid = 21237645 | doi = 10.1016/j.breast.2010.12.005 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| The major causes of sporadic breast cancer are associated with hormone levels. Breast cancer is promoted by estrogen. This hormone activates the development of breast throughout puberty, menstrual cycles and pregnancy. The imbalance between estrogen and progesterone during the menstrual phases causes cell proliferation. Moreover, oxidative metabolites of estrogen can increase DNA damage and mutations. Repeated cycling and the impairment of repair process can transform a normal cell into pre-malignant and eventually malignant cell through mutation. During the premalignant stage, high proliferation of stromal cells can be activated by estrogen to support the development of breast cancer. During the ligand binding activation, the ER can regulate gene expression by interacting with estrogen response elements within the promotor of specific genes. The expression and activation of ER due to lack of estrogen can be stimulated by extracellular signals.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Williams C, Lin CY | title = Oestrogen receptors in breast cancer: basic mechanisms and clinical implications | journal = ecancermedicalscience | volume = 7 | pages = 370 | date = November 2013 | pmid = 24222786 | pmc = 3816846 | doi = 10.3332/ecancer.2013.370 }}</ref> Interestingly, the ER directly binding with the several proteins, including growth factor receptors, can promote the expression of genes related to cell growth and survival.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Levin ER, Pietras RJ | title = Estrogen receptors outside the nucleus in breast cancer | journal = Breast Cancer Research and Treatment | volume = 108 | issue = 3 | pages = 351–361 | date = April 2008 | pmid = 17592774 | doi = 10.1007/s10549-007-9618-4 | s2cid = 11394158 }}</ref> | |||

| Raised ] levels in the blood are associated with increased risk of breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang M, Wu X, Chai F, Zhang Y, Jiang J | title = Plasma prolactin and breast cancer risk: a meta- analysis | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 6 | pages = 25998 | date = May 2016 | pmid = 27184120 | pmc = 4869065 | doi = 10.1038/srep25998 | bibcode = 2016NatSR...625998W }}</ref> A meta-analysis of observational research with over two million individuals has suggested a moderate association of antipsychotic use with breast cancer, possibly mediated by prolactin-inducing properties of specific agents.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Leung JC, Ng DW, Chu RY, Chan EW, Huang L, Lum DH, Chan EW, Smith DJ, Wong IC, Lai FT | display-authors = 6 | title = Association of antipsychotic use with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies with over 2 million individuals | journal = Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences | volume = 31 | pages = e61 | date = September 2022 | pmid = 36059215 | pmc = 9483823 | doi = 10.1017/S2045796022000476 }}</ref> | |||

| == Pathophysiology == | |||

| {{See also|Carcinogenesis}} | |||

| ] and lobules, the main locations of breast cancers]] | |||

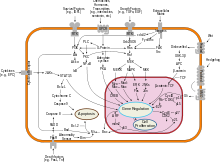

| ]. Mutations leading to loss of this ability can lead to cancer formation.]] | |||

| Breast cancer, like other ], occurs because of an interaction between an environmental (external) factor and a genetically susceptible host. Normal cells divide as many times as needed and stop. They attach to other cells and stay in place in tissues. Cells become cancerous when they lose their ability to stop dividing, to attach to other cells, to stay where they belong, and to die at the proper time. | |||

| Normal cells will self-destruct (]) when they are no longer needed. Until then, cells are protected from programmed death by several protein clusters and pathways. One of the protective pathways is the ]/] pathway; another is the ]/]/] pathway. Sometimes the genes along these protective pathways are mutated in a way that turns them permanently "on", rendering the cell incapable of self-destructing when it is no longer needed. This is one of the steps that causes cancer in combination with other mutations. Normally, the ] protein turns off the PI3K/AKT pathway when the cell is ready for programmed cell death. In some breast cancers, the gene for the PTEN protein is mutated, so the PI3K/AKT pathway is stuck in the "on" position, and the cancer cell does not self-destruct.<ref>{{cite conference | vauthors = Lee A, Arteaga C |title = 32nd Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium |book-title = Sunday Morning Year-End Review |date = 14 December 2009 |url = http://www.sabcs.org/Newsletter/Docs/SABCS_2009_Issue5.pdf |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130813021816/http://www.sabcs.org/Newsletter/Docs/SABCS_2009_Issue5.pdf |archive-date = 13 August 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| Mutations that can lead to breast cancer have been experimentally linked to estrogen exposure.<ref name="pmid16675129">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cavalieri E, Chakravarti D, Guttenplan J, Hart E, Ingle J, Jankowiak R, Muti P, Rogan E, Russo J, Santen R, Sutter T | display-authors = 6 | title = Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers: implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention | journal = Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer| volume = 1766 | issue = 1 | pages = 63–78 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16675129 | doi = 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.03.001 }}</ref> Additionally, G-protein coupled ]s have been associated with various cancers of the female reproductive system including breast cancer.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Filardo EJ | title = A role for G-protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) in estrogen-induced carcinogenesis: Dysregulated glandular homeostasis, survival and metastasis | journal = The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology | volume = 176 | pages = 38–48 | date = February 2018 | pmid = 28595943 | doi = 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.05.005 | s2cid = 19644829 }}</ref> | |||

| Abnormal ] signaling in the interaction between ]s and ]s can facilitate malignant cell growth.<ref name="pmid12817994">{{cite journal | vauthors = Haslam SZ, Woodward TL | title = Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: epithelial-cell-stromal-cell interactions and steroid hormone action in normal and cancerous mammary gland | journal = Breast Cancer Research | volume = 5 | issue = 4 | pages = 208–15 | date = June 2003 | pmid = 12817994 | pmc = 165024 | doi = 10.1186/bcr615 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wiseman BS, Werb Z | title = Stromal effects on mammary gland development and breast cancer | journal = Science | volume = 296 | issue = 5570 | pages = 1046–9 | date = May 2002 | pmid = 12004111 | pmc = 2788989 | doi = 10.1126/science.1067431 | bibcode = 2002Sci...296.1046W }}</ref> In breast adipose tissue, overexpression of leptin leads to increased cell proliferation and cancer.<ref name="pmid20889333">{{cite journal | vauthors = Jardé T, Perrier S, Vasson MP, Caldefie-Chézet F | title = Molecular mechanisms of leptin and adiponectin in breast cancer | journal = European Journal of Cancer | volume = 47 | issue = 1 | pages = 33–43 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 20889333 | doi = 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.005 }}</ref> | |||