| Revision as of 18:07, 10 December 2007 editRussBot (talk | contribs)Bots1,407,845 editsm Robot: Fixing double-redirect -"Alcohol consumption and health" +"Long-term effects of alcohol"← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:01, 18 February 2013 edit undoDavid Hedlund (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,269 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ==Alcohol and health== | |||

| #REDIRECT ] | |||

| {{See also|Template:Alcohol and health}} | |||

| ] consumption include ] and ]. ] include changes in the metabolism of the liver and brain and ] (addiction to alcohol). | |||

| Alcohol intoxication affects the brain, causing slurred speech, clumsiness, and delayed reflexes. Alcohol stimulates ] production, which speeds up ] ] and can result in low ], causing irritability and (for ]) possible death. Severe alcohol poisoning can be fatal. | |||

| A ] of 0.45% in test animals results in a median lethal dose of {{LD50}}. This means that 0.45% is the concentration of blood alcohol that is fatal in 50% of the test subjects. That is about six times the level of ordinary intoxication (0.08%), but ] or unconsciousness may occur much sooner in people who have a low tolerance for alcohol.<ref name="psychopharm">Meyer, Jerold S. and Linda F. Quenzer. Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior. Sinauer Associates, Inc: Sunderland, Massachusetts. 2005. Page 228.</ref> The high tolerance of chronic heavy drinkers may allow some of them to remain conscious at levels above 0.40%, although serious health dangers are incurred at this level. | |||

| Alcohol also limits the production of ] (ADH) from the ] and the secretion of this ] from the ] gland. This is what causes severe ] when large amounts of alcohol are drunk. It also causes a high concentration of water in the ] and vomit and the intense thirst that goes along with a ]. | |||

| ], ]s and ] may increase the desire<!--crave?--> for alcohol because these things will lower the level of testosterone and alcohol will acutely elevate it.<ref>, Helsinki 2001</ref> ] has the same effect of increasing the craving for alcohol.<ref>, ESBRA 2009</ref> | |||

| ===Abuse prevention=== | |||

| {{see also|Substance abuse prevention}} | |||

| ====Alcohol abuse prevention programs==== | |||

| {{see also|Prevention Science}} | |||

| =====0-1-2-3===== | |||

| The Army at Fort Drum has taken the “0-0-1-3” and exchanged it for the new “0-1-2-3” described in the Prime-For-Life Program, which highlights the ill effects of alcohol abuse as more than just an individual’s “driving while intoxicated.” The Prime-For-Life program identifies alcohol abuse to be a health and impairment problem, leading to adverse legal as well as health outcomes associated with misuse. | |||

| The 0-1-2-3 now represents low-risk guidelines: | |||

| * 0 – Zero drinks for those driving a vehicle. | |||

| * 1 – One drink per hour | |||

| * 2 – No more than two drinks per day | |||

| * 3 – Not to exceed three drinks on any one day | |||

| ====Recommended maximum intake==== | |||

| {{Main|Recommended maximum intake of alcoholic beverages}} | |||

| Binge drinking is becoming a major problem in the UK. Advice on weekly consumption is avoided in United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aim-digest.com/gateway/pages/guide/articles/biggy.htm |title=Sensible Drinking |publisher=Aim-digest.com |date= |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| Since 1995 the UK government has advised that regular consumption of 3–4 units a day for men, or 2–3 units a day for women, would not pose significant health risks, but that consistently drinking four or more units a day (men), or three or more units a day (women), is not advisable.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthimprovement/Alcoholmisuse/index.htm |title=Alcohol misuse : Department of Health |publisher=Dh.gov.uk |date= |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| Previously (from 1992 until 1995), the advice was that men should drink no more than 21 units per week, and women no more than 14.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/factsheets/health-fact-sample-2 |title=Alcohol and health: how alcohol can affect your long and short term health |publisher=Drinkaware.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> (The difference between the sexes was due to the typically lower weight and water-to-body-mass ratio of women.) This was changed because a government study showed that many people were in effect "saving up" their units and using them at the end of the week, a phenomenon referred to as ].{{Citation needed|date= October 2007}} ] reported in October 2007 that these limits had been "plucked out of the air" and had no scientific basis.<ref>, The Times, 20 October 2007</ref> | |||

| ====Sobriety==== | |||

| {{see also|Sobriety}} | |||

| ] is subjected to a random ] test to see if he is sober or not.]] | |||

| '''Sobriety''' is the condition of not having any measurable levels, or effects from ]s. According to WHO "Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms..." '''sobriety''' is continued abstinence from psychoactive drug use.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/terminology/who_lexicon/en/ |title=Lexicon and drug terms |publisher=Who.int |date=2010-12-09 |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> Sobriety is also considered to be the natural state of a human being given at a birth. In a treatment setting, sobriety is the achieved goal of independence from consuming or craving mind-altering substances. As such, sustained abstinence is a prerequisite for sobriety. Early in abstinence, residual effects of mind-altering substances can preclude sobriety. These effects are labeled "PAWS", or "post acute withdrawal syndrome". Someone who abstains, but has a latent desire to resume use, is not considered truly sober. An abstainer may be subconsciously motivated to resume drug use, but for a variety of reasons, abstains (e.g. such as a medical or legal concern precluding use).<ref name="basharin">{{cite web|url=http://www.video.sbnt.ru/vl/Newspapers/Podsporie/Podsporie_111.pdf |title=Scientific grounding for sobriety: Western experience |authors=MD Basharin K.G., Yakutsk State University |format=PDF |date=2010 |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> Sobriety has more specific meanings within specific contexts, such as the culture of ], other 12 step programs, law enforcement, and some schools of psychology. In some cases, '''sobriety''' implies achieving "life balance."<ref>{{dead link|date=February 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ===Mortality rate=== | |||

| {{Main|Long-term effects of alcohol#Alcohol-related deaths}} | |||

| A report of the United States ] estimated that medium and high consumption of alcohol led to 75,754 deaths in the U.S. in 2001. Low consumption of alcohol had some beneficial effects, so a net 59,180 deaths were attributed to alcohol.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5337a2.htm|title=Alcohol-Attributable Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost — United States, 2001|date=2004-09-24|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| In the ], heavy drinking is blamed for about 33,000 deaths a year.<ref>{{Cite news|publisher=BBC News|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/medical_notes/a-b/872428.stm|title=Alcohol|date=2000-08-09}}</ref> | |||

| A study in ] found that 29% to 44% of "unnatural" deaths (those not caused by illness) were related to alcohol. The causes of death included murder, suicide, falls, ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite news|publisher=BBC News|date=2000-07-14|title=Alcohol linked to thousands of deaths|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/833483.stm}}</ref> | |||

| A global study found that 3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are caused by alcohol drinking, resulting in 3.5% of all global cancer deaths.<ref name="abramson">{{Cite news|title=Burden of alcohol-related cancer substantial|url=http://www.oncolink.com/resources/article.cfm?c=3&s=8&ss=23&id=13383&month=08&year=2006| date=2006-08-03|publisher=Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania}}</ref> A study in the ] found that alcohol causes about 6% of cancer deaths in the UK (9,000 deaths per year).<ref name="cancer1"/> | |||

| ====ISCD==== | |||

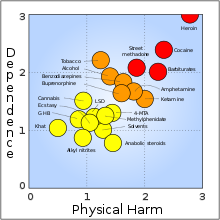

| ] 2010 study ranking the levels of damage caused by drugs, in the opinion of drug-harm experts. When harm to self and others is summed, alcohol was the most harmful of all drugs considered, scoring 72%.]] | |||

| ]'' in 2007 by David Nutt (now chair of ]) shows alcohol in comparison to other psychoactive drugs, scoring 1.40, 1.93, and 2.21 of possible 3 ranking points for physical harm, dependence, and social harm respectively.<ref name="Nutt">{{cite pmid|17382831}}</ref>]] | |||

| A 2010 study by the ], led by ], Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, asked drug-harm experts to rank a selection of illegal and legal drugs on various measures of harm both to the user and to others in society. These measures include damage to health, drug dependency, economic costs and crime. The researchers claim that the rankings are stable because they are based on so many different measures and would require significant discoveries about these drugs to affect the rankings.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2010/11/drugs_cause_most_harm |title=Drugs that cause most harm: Scoring drugs |publisher=The Economist |date=2010-11-02 |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| Despite being legal more often than the other drugs, alcohol was considered to be by far the most harmful; not only was it regarded as the most damaging to societies, it was also seen as the fourth most dangerous for the user. Most of the drugs were rated significantly less harmful than alcohol, with most of the harm befalling the user. | |||

| The authors explain that one of the limitation of this study is that drug harms are functions of their availability and legal status in the UK, and so other cultures' control systems could yield different rankings. | |||

| ===Alcohol expectations=== | |||

| Alcohol expectations are ]s and ] that people have about the effects they will experience when drinking alcoholic beverages. They are largely beliefs about alcohol's effects on a person’s behaviors, abilities, and emotions. Some people believe that if alcohol expectations can be changed, then ] might be reduced.<ref name=Grattan>{{cite journal |last1=Grattan |first1=Karen E. |last2=Vogel-Sprott |first2=M. |title=Maintaining Intentional Control of Behavior Under Alcohol |journal=Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=192–7 |year=2001 |doi=10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02198.x |pmid=11236832}}</ref> | |||

| The phenomenon of alcohol expectations recognizes that intoxication has real physiological consequences that alter a drinker's perception of space and time, reduce psychomotor skills, and disrupt ].<ref name=MacAndrew/> The manner and degree to which alcohol expectations interact with the physiological short-term effects of alcohol, resulting in specific behaviors, is unclear. | |||

| A single study found, if a society believes that intoxication leads to ], rowdy behavior, or aggression, then people tend to act that way when intoxicated. But if a society believes that intoxication leads to relaxation and tranquil behavior, then it usually leads to those outcomes. Alcohol expectations vary within a society, so these outcomes are not certain.<ref name="The think-drink effect">{{cite journal | last1 = Marlatt | first1 = G. A. | last2 = Rosenow | first2 = | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | year = 1981 | title = The think-drink effect | url = | journal = Psychology Today | volume = 15 | issue = | pages = 60–93 }}</ref> | |||

| People tend to conform to social expectations, and some societies expect that drinking alcohol will cause ]. However, in societies in which the people do not expect that alcohol will disinhibit, intoxication seldom leads to disinhibition and bad behavior.<ref name=MacAndrew>MacAndrew, C. and Edgerton. ''Drunken Comportment: A Social Explanation''. Chicago: Aldine, 1969.</ref> | |||

| Alcohol expectations can operate in the absence of actual consumption of alcohol. Research in the United States over a period of decades has shown that men tend to become more sexually aroused when they think they have been drinking alcohol, — even when they have not been drinking it. Women report feeling more sexually aroused when they falsely believe the beverages they have been drinking contained alcohol (although one measure of their physiological arousal shows that they became less aroused).{{Citation needed|date=June 2010}} | |||

| Men tend to become more aggressive in laboratory studies in which they are drinking only ] but believe that it contains alcohol. They also become less aggressive when they believe they are drinking only tonic water, but are actually drinking tonic water that contains alcohol.<ref name=Grattan/> | |||

| ===Genetic differences=== | |||

| ====Alcohol flush reaction==== | |||

| {{see also|Alcohol flush reaction}} | |||

| Alcohol flush reaction is best known as a condition that is experienced by people of Asian descent. According to the analysis by ] project, the rs671 allele of the ALDH2 gene responsible for the flush reaction is rare among Europeans and Africans, and it is very rare among Mexican-Americans. 30% to 50% of people of Chinese and Japanese ancestry have at least one ALDH*2 allele.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.snpedia.com/index.php/Rs671|title=Rs671}}</ref> The rs671 form of ALDH2, which accounts for most incidents of alcohol flush reaction worldwide, is native to East Asia and most common in southeastern China. It most likely originated among Han Chinese in central China,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Refined Geographic Distribution of the Oriental ALDH2*504Lys (nee 487Lys) Variant|author=Hui Li et al|journal=Ann Hum Genet|year=2009|pmc=2846302|pmid=19456322|doi=10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00517.x|volume=73|issue=Pt 3|pages=335–45}}</ref> and it appears to have been positively selected in the past. Another analysis correlates the rise and spread of rice cultivation in Southern China with the spread of the allele.<ref name="Yi Peng, Hong Shi, Xue-bin Qi, Chun-jie Xiao, Hua Zhong, Run-lin Z Ma, Bing Su 2010 15">{{cite journal |author=Yi Peng, Hong Shi, Xue-bin Qi, Chun-jie Xiao, Hua Zhong, Run-lin Z Ma, Bing Su |title=The ADH1B Arg47His polymorphism in East Asian populations and expansion of rice domestication in history |journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology |volume=10 |page= 15|year=2010 |pmid=20089146 |pmc=2823730 |doi= 10.1186/1471-2148-10-15|url=http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/15}}</ref> The reasons for this positive selection aren't known, but it's been hypothesized that elevated concentrations of acetaldehyde may have conferred protection against certain parasitic infections, such as '']''.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Oota et al|title=The evolution and population genetics of the ALDH2 locus: random genetic drift, selection, and low levels of recombination|year=2004|journal=Annals of Human Genetics}}</ref> | |||

| ====American Indian alcoholism==== | |||

| {{see also|American Indian alcoholism}} | |||

| While little detailed genetic research has been done, it has been shown that alcoholism tends to run in families with possible involvement of differences in alcohol metabolism and the genotype of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes. | |||

| ===Gender differences=== | |||

| ====Sensitivity==== | |||

| Several biological factors make women more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol than men.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.helpguide.org/harvard/women_alcohol.htm |title=Women & Alcohol: The Hidden Risks of Drinking |publisher=Helpguide.org |date= |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| * Body fat. Women tend to weigh less than men, and—pound for pound—a woman’s body contains less water and more fatty tissue than a man’s. Because fat retains alcohol while water dilutes it, alcohol remains at higher concentrations for longer periods of time in a woman’s body, exposing her brain and other organs to more alcohol. | |||

| * Enzymes. Women have lower levels of two enzymes—alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase—that metabolize (break down) alcohol in the stomach and liver. As a result, women absorb more alcohol into their bloodstreams than men. | |||

| * Hormones. Changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle may also affect how a woman metabolizes alcohol. | |||

| ====Metabolism==== | |||

| Females demonstrated a higher average rate of elimination (mean, 0.017; range, 0.014-0.021 g/210 L) than males (mean, 0.015; range, 0.013-0.017 g/210 L). Female subjects on average had a higher percentage of body fat (mean, 26.0; range, 16.7-36.8%) than males (mean, 18.0; range, 10.2-25.3%).<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8872236</ref> | |||

| ====Depression==== | |||

| The link between alcohol consumption, depression, and gender was examined by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada). The study found that women taking antidepressants consumed more alcohol than women who did not experience depression as well as men taking antidepressants. The researchers, Dr. Kathryn Graham and a PhD Student Agnes Massak analyzed the responses to a survey by 14,063 Canadian residents aged 18–76 years. The survey included measures of quantity, frequency of drinking, depression and antidepressants use, over the period of a year. The researchers used data from the GENACIS Canada survey, part of an international collaboration to investigate the influence of cultural variation on gender differences in alcohol use and related problems. The purpose of the study was to examine whether, like in other studies already conducted on male depression and alcohol consumption, depressed women also consumed less alcohol when taking anti-depressants.<ref>“Antidepressants Help Men, But Not Women, Decrease Alcohol Consumption.” Science Daily. Feb. 27, 2007.</ref> | |||

| According to the study, both men and women experiencing depression (but not on anti-depressants) drank more than non-depressed counterparts. Men taking antidepressants consumed significantly less alcohol than depressed men who did not use antidepressants. Non-depressed men consumed 436 drinks per year, compared to 579 drinks for depressed men not using antidepressants, and 414 drinks for depressed men who used antidepressants. Alcohol consumption remained higher whether the depressed women were taking anti-depressants or not. 179 drinks per year for non-depressed women, 235 drinks for depressed women not using antidepressants, and 264 drinks for depressed women who used antidepressants. The lead researcher argued that the study "suggests that the use of antidepressants is associated with lower alcohol consumption among men suffering from depression. But this does not appear to be true for women."<ref>Graham, Katherine and Massak, Agnes. “Alcohol consumption and the use of antidepressants.” UK Pubmed Central (2007). June 20, 2012.</ref> | |||

| ===Short-term effects of alcohol=== | |||

| {{See also|Alcohol and sex|Blood alcohol content|Alcohol intoxication|Short-term effects of alcohol}} | |||

| ====Blood ethanol concentration (BEC)==== | |||

| {{See also|Blood alcohol content}} | |||

| ] | |||

| =====Vehicle operation===== | |||

| The number of serious errors committed by pilots dramatically increases at or above concentrations of 0.04% blood alcohol. This is not to say that problems don't occur below this value. Some studies have shown decrements in pilot performance with blood alcohol concentrations as low as the 0.025%.<ref><http://flightphysical.com/pilot/alcohol.htm/</ref> Also, a BEC of ≥0.080 or more is legally intoxicated for driving in MOST states. And, ≤0.050 is considered NOT impaired in most.<ref>http://info.insure.com/auto/baccalc.html</ref> | |||

| =====Estimated blood ethanol concentration (EBAC)===== | |||

| In order to calculate estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (EBAC) a variation, including drinking period in hours, of the Widmark formula was used. The formula is:<ref name=PMC2724514/> | |||

| :<math>EBAC = 10 \cdot \frac {0.806 \cdot SD \cdot 1.2}{BW \cdot Wt} - (MR \cdot DP)</math> | |||

| where 0.806 is a constant for body water in the blood (mean 80.6%), SD is the number of standard drinks containing 10 grams of ethanol, 1.2 is a factor in order to convert the amount in grams to Swedish standards set by The Swedish National Institute of Public Health, BW is a body water constant (0.58 for men and 0.49 for women), Wt is body weight (kilogram), MR is the metabolism constant (0.017), DP is the drinking period in hours and 10 converts the result to permillage of alcohol.<ref name=PMC2724514>{{cite journal |doi=10.1186/1471-2458-9-229 |title=Alcohol use among university students in Sweden measured by an electronic screening instrument |year=2009 |last1=Andersson |first1=Agneta |last2=Wiréhn |first2=Ann-Britt |last3=Ölvander |first3=Christina |last4=Ekman |first4=Diana |last5=Bendtsen |first5=Preben |journal=BMC Public Health |volume=9 |page=229 |pmid=19594906 |pmc=2724514}}</ref> Regarding metabolism (MR) in the formula; Females demonstrated a higher average rate of elimination (mean, 0.017; range, 0.014-0.021 g/210 L) than males (mean, 0.015; range, 0.013-0.017 g/210 L). Female subjects on average had a higher percentage of body fat (mean, 26.0; range, 16.7-36.8%) than males (mean, 18.0; range, 10.2-25.3%).<ref>{{cite journal |pmid=8872236 |url=http://jat.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=8872236 |doi=10.1093/jat/20.5.287 |year=1996 |last1=Cowan Jr |first1=JM |last2=Weathermon |first2=A |last3=McCutcheon |first3=JR |last4=Oliver |first4=RD |title=Determination of volume of distribution for ethanol in male and female subjects |volume=20 |issue=5 |pages=287–90 |journal=Journal of analytical toxicology |doi_brokendate=February 5, 2013}}</ref> Additionally, men are, on average, heavier than women but it is not strictly accurate to say that the water content of a person alone is responsible for the dissolution of alcohol within the body, because alcohol does dissolve in fatty tissue as well. When it does, a certain amount of alcohol is temporarily taken out of the blood and briefly stored in the fat. For this reason, most calculations of alcohol to body mass simply use the weight of the individual, and not specifically his water content. Further, studies have shown that women's alcohol metabolism varies from that of men due to such biochemical factors as different levels of ] (the enzyme which breaks down alcohol) and the effects of oral contraceptives.<ref></ref> Finally, it is speculated that the bubbles in sparkling wine may speed up ] by helping the alcohol to reach the bloodstream faster. A study conducted at the ] in the United Kingdom gave subjects equal amounts of flat and sparkling Champagne which contained the same ]. After 5 minutes following consumption, the group that had the sparkling wine had 54 milligrams of alcohol in their blood while the group that had the same sparkling wine, only flat, had 39 milligrams.<ref name="Miscellany">G. Harding ''"A Wine Miscellany"'' pg 136–137, Clarkson Potter Publishing, New York 2005 ISBN 0-307-34635-8</ref> | |||

| Examples: | |||

| * 80 kg male drinking 3 standard drinks in two hours: | |||

| :<math> EBAC = (0.806 \cdot 3 \cdot 1.2)/(0.58 \cdot 80) - (0.015 \cdot 2) = 0.032534483 \approx 0.033 g/dL</math> | |||

| * 70 kg woman drinking 2.5 standard drinks in two hours: | |||

| :<math> EBAC = (0.806 \cdot 3 \cdot 1.2)/(0.49 \cdot 70) - (0.017 \cdot 2) = 0.036495627 \approx 0.037 g/dL</math> | |||

| Useful tools: | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| =====Binge drinking===== | |||

| {{see also|Binge drinking}} | |||

| In most jurisdictions a measurement such as a blood alcohol content (BAC) in excess of a specific threshold level, such as 0.05% or 0.08% defines the offense. Also, the ] (NIAAA) define the term "]" as any time one reaches a peak BAC of 0.08% or higher as opposed to some (arguably) arbitrary number of drinks in an evening.<ref name="cdc.gov">"Quick Stats: Binge Drinking." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2008..</ref> | |||

| ======Pleasure zone====== | |||

| Known as ''pleasure zone'', the positive exceeds the negative effects typically between '''0.030–0.059%''' blood ethanol concentration (BEC), but contrary at higher volumes like ] (0.08% as defined by NIAAA). | |||

| ======BEC chart====== | |||

| The data below apply '''specifically to ethanol''', not other '''alcohols''' found in alcoholic beverage. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Colspan="3" | Progressive effects of alcohol<ref>A hybridizing of effects as described at '''' from ] and (hosted on ''FlightPhysical.com'')</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! BAC (% by vol.) | |||

| ! Behavior | |||

| ! Impairment | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.010–0.029 | |||

| | | |||

| * Average individual appears<br />normal | |||

| | | |||

| * Subtle effects that can be<br />detected with special tests | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.030–0.059 | |||

| | | |||

| * Mild ] | |||

| * Relaxation | |||

| * Joyousness | |||

| * Talkativeness | |||

| * Decreased inhibition | |||

| | | |||

| * Concentration | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.06–0.09 | |||

| | | |||

| * Blunted feelings | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Extroversion | |||

| | | |||

| * Reasoning | |||

| * Depth perception | |||

| * Peripheral vision | |||

| * Glare recovery | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.10–0.19 | |||

| | | |||

| * Over-expression | |||

| * Emotional swings | |||

| * Anger or sadness | |||

| * Boisterousness | |||

| * Decreased libido | |||

| | | |||

| * Reflexes | |||

| * Reaction time | |||

| * Gross motor control | |||

| * Staggering | |||

| * Slurred speech | |||

| * Temporary erectile dysfunction | |||

| * Possibility of temporary alcohol poisoning | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.20–0.29 | |||

| | | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Loss of understanding | |||

| * Impaired sensations | |||

| * Possibility of falling unconscious | |||

| | | |||

| * Severe motor impairment | |||

| * Loss of consciousness | |||

| * ] blackout | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.30–0.39 | |||

| | | |||

| * Severe ] | |||

| * Unconsciousness | |||

| * Death is possible | |||

| | | |||

| * Bladder function | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| 0.40–0.50 | |||

| | | |||

| * General lack of behavior | |||

| * Unconsciousness | |||

| | | |||

| * Breathing | |||

| * Heart rate | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;"| >0.50 | |||

| | | |||

| * High risk of poisoning | |||

| * Possibility of death | |||

| |} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Colspan="6" | Standard drink chart (U.S.)<ref>Based on the ] standard of 0.6 fl oz alcohol per drink. </ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Alcohol | |||

| ! Amount (ml) | |||

| ! Amount (fl oz) | |||

| ! Serving size | |||

| ! Alcohol (% by vol.) | |||

| ! Alcohol | |||

| |- | |||

| | 80 proof liquor || 44 || 1.5 || One shot || 40 || {{convert|0.6|USoz|ml|abbr=on}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | Table wine || 148 || 5 || One glass || 12 || {{convert|0.6|USoz|ml|abbr=on}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | Beer || 355 || 12 || One can || 5 || {{convert|0.6|USoz|ml|abbr=on}} | |||

| |} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Male<br />Female !! Colspan="9"| Approximate blood alcohol percentage (by vol.)<ref> from ]</ref><br /><small>One drink has {{convert|0.5|USoz|ml|abbr=on}} alcohol by volume</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Rowspan="3"| Drinks !! Colspan="9"| Body weight | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 40 kg !! 45 kg !! 55 kg !! 64 kg !! 73 kg !! 82 kg !! 91 kg !! 100 kg !! 109 kg | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 90 lb !! 100 lb !! 120 lb !! 140 lb !! 160 lb !! 180 lb !! 200 lb !! 220 lb !! 240 lb | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 1 || –<br />0.05 || 0.04<br />0.05 || 0.03<br />0.04 || 0.03<br />0.03 || 0.02<br />0.03 || 0.02<br />0.03 || 0.02<br />0.02 || 0.02<br />0.02 || 0.02<br />0.02 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 2 || –<br />0.10 || 0.08<br />0.09 || 0.06<br />0.08 || 0.05<br />0.07 || 0.05<br />0.06 || 0.04<br />0.05 || 0.04<br />0.05 || 0.03<br />0.04 || 0.03<br />0.04 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 3 || –<br />0.15 || 0.11<br />0.14 || 0.09<br />0.11 || 0.08<br />0.10 || 0.07<br />0.09 || 0.06<br />0.08 || 0.06<br />0.07 || 0.05<br />0.06 || 0.05<br />0.06 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 4 || –<br />0.20 || 0.15<br />0.18 || 0.12<br />0.15 || 0.11<br />0.13 || 0.09<br />0.11 || 0.08<br />0.10 || 0.08<br />0.09 || 0.07<br />0.08 || 0.06<br />0.08 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 5 || –<br />0.25 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.16<br />0.19 || 0.13<br />0.16 || 0.12<br />0.14 || 0.11<br />0.13 || 0.09<br />0.11 || 0.09<br />0.10 || 0.08<br />0.09 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 6 || –<br />0.30 || 0.23<br />0.27 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.16<br />0.19 || 0.14<br />0.17 || 0.13<br />0.15 || 0.11<br />0.14 || 0.10<br />0.12 || 0.09<br />0.11 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 7 || –<br />0.35 || 0.26<br />0.32 || 0.22<br />0.27 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.16<br />0.20 || 0.15<br />0.18 || 0.13<br />0.16 || 0.12<br />0.14 || 0.11<br />0.13 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 8 || –<br />0.40 || 0.30<br />0.36 || 0.25<br />0.30 || 0.21<br />0.26 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.17<br />0.20 || 0.15<br />0.18 || 0.14<br />0.17 || 0.13<br />0.15 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | 9 || –<br />0.45 || 0.34<br />0.41 || 0.28<br />0.34 || 0.24<br />0.29 || 0.21<br />0.26 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.17<br />0.20 || 0.15<br />0.19 || 0.14<br />0.17 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| |10 || –<br />0.51 || 0.38<br />0.45 || 0.31<br />0.38 || 0.27<br />0.32 || 0.23<br />0.28 || 0.21<br />0.25 || 0.19<br />0.23 || 0.17<br />0.21 || 0.16<br />0.19 | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| | Colspan="10" | Subtract approximately 0.01 every 40 minutes after drinking. | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Long-term effects of alcohol=== | |||

| {{See also|Long-term effects of alcohol}} | |||

| ====Adverse effects of binge drinking (0.08% BAC or higher)==== | |||

| {{main|Binge drinking#Health effects}} | |||

| The ] (NIAAA) recently redefined the term "binge drinking" as any time one reaches a peak BAC of 0.08% or higher as opposed to some (arguably) arbitrary number of drinks in an evening.<ref name="cdc.gov"/> | |||

| =====Alcohol withdrawal syndrome===== | |||

| {{See also|Physical dependency}} | |||

| The severity of the ] can vary from mild symptoms such as mild sleep disturbances and mild anxiety to very severe and life threatening including ], particularly visual hallucinations in severe cases and convulsions (which may result in death).<ref name="eciawap">{{cite journal |author=Harada K |title=Emotional condition in alcohol withdrawal acute psychosis |journal=Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi |volume=95 |issue=7 |year=1993 |pages=523–9 |pmid=8234534}}</ref> This is sometimes referred to as alcohol-induced ]; Sedative hypnotic drugs such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates are the only commonly available substances that can be fatal in withdrawal due to their propensity to induce withdrawal convulsions. | |||

| =====High-functioning alcoholic (HFA)===== | |||

| {{see also|High-functioning alcoholic}} | |||

| A high-functioning alcoholic (HFA) is a form of ] where the alcoholic is able to maintain their outside life such as jobs, academics, relationships, etc.{{spaced ndash}}all while drinking alcoholically.<ref name="benton2009">{{cite book |title=Understanding the High-Functioning Alcoholic{{spaced ndash}}Professional Views and Personal Insights |last=Benton |first=Sarah Allen |year=2009 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-313-35280-5 }}</ref> | |||

| Many HFAs are not viewed by society as alcoholics because they do not fit the common alcoholic ]. Unlike the stereotypical alcoholic, HFAs have either succeeded or ] through their lifetimes. This can lead to ] of alcoholism by both the HFA, co-workers, family members and friends. Functional alcoholics account for 19.5 percent of total U.S. alcoholics, with 50 percent being smokers and 33 percent having a multigenerational family history of alcoholism.<ref>{{cite web|title=Researchers Identify Alcoholic Subtypes|url=http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/jun2007/niaaa-28.htm|publisher=]{{spaced ndash}}] |accessdate= February 18, 2012|author= Press release | date =June 28, 2007}}</ref> | |||

| =====Alcoholism===== | |||

| {{Main|Alcoholism}} | |||

| Alcohol is the most available and widely abused substance; Beer alone is the world's most widely consumed<ref>{{cite web|title=Volume of World Beer Production|work=European Beer Guide|url=http://www.europeanbeerguide.net/eustats.htm#production|accessdate=17 October 2006| archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20061028165040/http://www.europeanbeerguide.net/eustats.htm| archivedate= 28 October 2006 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> ]; it is the third-most popular drink overall, after ] and ].<ref name="Nelson 2005">{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=6xul0O_SI1MC&pg=PA1&dq=most+consumed+beverage|title=The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe|year=2005|publisher=Routledge|location=Abingdon, Oxon|isbn=0-415-31121-7|page=1|accessdate=21 September 2010|last= Nelson|first=Max}}</ref> It is thought by some to be the oldest fermented beverage.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Alchemy of Culture: Intoxicants in Society|first=Richard|last=Rudgley|isbn=978-0-7141-1736-2|year=1993|pages=411|url=http://books.google.com/?id=5baAAAAAMAAJ&q=The+Alchemy+of+Culture&dq=The+Alchemy+of+Culture|publisher=British Museum Press|location=London|accessdate=13 January 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology|first=John P|last=Arnold|isbn=0-9662084-1-2|year=2005|pages=411|url=http://books.google.com/?id=O5CPAAAACAAJ&dq=Origin+and+History+of+Beer+and+Brewing|publisher=Reprint Edition by BeerBooks|location=Cleveland, Ohio|accessdate=13 January 2012}}</ref><ref>Joshua J. Mark (2011). . Ancient History Encyclopedia.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=SHh-4M_QxEsC&pg=PA10&dq=oldest+beverage&q=oldest%20beverage |title=World's Best Beers: One Thousand |publisher=Google Books |accessdate=7 August 2010 |isbn=978-1-4027-6694-7 |date=6 October 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| Under the ]'s new definition of Alcoholism about 37 percent of college students may meet the criteria. Doctors are hoping that this new definition of the term will help catch severe cases of alcoholism early, instead of when the problem is full-blown.<ref name="dailyemerald1">{{cite web|url=http://dailyemerald.com/2012/05/22/redefining-alcoholic-what-this-means-for-students/ |title=About 37 percent of college students could now be considered alcoholics |publisher=Dailyemerald.com |date=2012-05-22 |accessdate=2013-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| Based on combined data from SAMHSA's 2004-2005 National Surveys on Drug Use & Health, the rate of past year alcohol dependence or abuse among persons aged 12 or older varied by level of alcohol use: 44.7% of past month heavy drinkers, 18.5% binge drinkers, 3.8% past month non-binge drinkers, and 1.3% of those who did not drink alcohol in the past month met the criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse in the past year. Males had higher rates than females for all measures of drinking in the past month: any alcohol use (57.5% vs. 45%), binge drinking (30.8% vs. 15.1%), and heavy alcohol use (10.5% vs. 3.3%), and males were twice as likely as females to have met the criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse in the past year (10.5% vs. 5.1%).<ref>“Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol dependence or abuse: 2004 or 2005.” The NSDUH Report.Accessed June 22, 2012.</ref> | |||

| The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines binge drinking as the amount of alcohol leading to a blood alcohol content (BAC) of 0.08, which, for most adults, would be reached by consuming five drinks for men or four for women over a 2-hour period. | |||

| According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism , men may be at risk for alcohol-related problems if their alcohol consumption exceeds 14 standard drinks per week or 4 drinks per day, and women may be at risk if they have more than 7 standard drinks per week or 3 drinks per day. A standard drink is defined as one 12-ounce bottle of beer, one 5-ounce glass of wine, or 1.5 ounces of distilled spirits.)<ref>http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa68/aa68.htm</ref> | |||

| Alcoholism can lead to malnutrition because it can alter digestion and the metabolism of most nutrients. Severe ] deficiency is common in alcoholism due to deficiency of ], ], ], and ] ; this can lead to ]. ] is also associated with a type of dementia called ], which is caused by a deficiency in ] (vitamin B<sub>1</sub>).<ref name=Oscar-Berman2003>{{Cite journal|author=Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K |title=Alcoholism and the brain: an overview |journal=Alcohol Res Health |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=125–33 |year=2003 |pmid=15303622 |doi= |url=}} .</ref> Muscle cramps, nausea, loss of appetite, nerve disorders, and depression are common symptoms of alcoholism. ] and bone fractures may occur due to deficiency of ]. | |||

| =====Cancer===== | |||

| {{Main|Alcohol and cancer}} | |||

| Alcohol consumption has been linked with seven types of cancer: ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name="cancer1">{{cite web|title=Alcohol and cancer|url=http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/healthyliving/alcohol/|publisher=]}}</ref> Heavy drinkers are more likely to develop liver cancer due to ].<ref name="cancer1"/> The risk of developing cancer increases even with consumption of as little as three ] (one pint of lager or a large glass of wine) a day.<ref name="cancer1"/> | |||

| A global study found that 3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are caused by drinking alcohol, resulting in 3.5% of all global cancer deaths.<ref name="abramson"/> A study in the ] found that alcohol causes about 6% of cancer deaths in the UK (9,000 deaths per year).<ref name="cancer1"/> A study in ] found that alcohol causes about 4.40% of all cancer deaths and 3.63% of all cancer incidences.<ref name="Liang 2010">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1186/1471-2458-10-730 | last1 = Liang | first1 = H. | last2 = Wang | year = 2010 | first2 = Jianbing | last3 = Xiao | first3 = Huijuan | last4 = Wang | first4 = Ding | last5 = Wei | first5 = Wenqiang | last6 = Qiao | first6 = Youlin | last7 = Boffetta | first7 = Paolo | title = Estimation of cancer incidence and mortality attributable to alcohol drinking in China | url = http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/730 | journal = BMC Public Health | volume = 10 | issue = 1| page = 730 }}</ref> For both men and women, the consumption of two or more drinks daily increases the risk of pancreatic cancer by 22%.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/140882.php|title=Alcohol Consumption May Increase Pancreatic Cancer Risk|publisher=Medical News Today|date=2009-03-04}}</ref> | |||

| Women who regularly consume low to moderate amounts of alcohol have an increased risk of cancer of the upper digestive tract, rectum, liver, and breast.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://professional.cancerconsultants.com/oncology_main_news.aspx?id=43299|title=Moderate Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Cancer in Women|date=2009-03-10}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/140882.php |title=Alcohol Consumption May Increase Pancreatic Cancer Risk |publisher=Medicalnewstoday.com |date= |accessdate=2010-02-11}}</ref> | |||

| Red wine contains ], which has some anti-cancer effect. However, based on studies done so far, there is no strong evidence that red wine protects against cancer in humans.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/healthyliving/alcohol/benefits/|title=Can alcohol be good for you?|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| Recent studies indicate that Asian populations are particularly prone to carcinogenic effects of alcohol. It's been noted that ethanol's byproducts in metabolism results in ]. In non-Asian populations, an enzyme called ] that quickly converts acetaldehyde into ]. Asian populations have a variant form of alcohol dehydrogenase which prevents conversion of the acetaldehyde. This substance has been indicated to have strong interactions with DNA and thereby causing carcinogenic effects.<ref>http://www.kurzweilai.net/alcohol-may-boost-risk-of-cancer-for-asians</ref><ref>Silvia Balbo, Lei Meng, Robin L. Bliss, Joni A. Jensen, Dorothy K. Hatsukami, Stephen S. Hecht, Kinetics of DNA Adduct Formation in the Oral Cavity after Drinking Alcohol, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2012, DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1175</ref> | |||

| =====Dementia===== | |||

| {{Main|Alcohol dementia}} | |||

| Excessive drinking has been linked to ]; it is estimated that 10% to 24% of dementia cases are caused by alcohol consumption, with women being at greater risk than men.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nhs.uk/news/2009/05may/pages/alcoholmajordementiacause.aspx|title=Alcohol 'major cause of dementia'|publisher=]|date=2008-05-11}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2009/may/10/alcohol-intake-dementia-memory-loss|publisher=The Guardian|title=Binge drinking 'increases risk' of dementia|date=2009-05-10 | location=London | first=Denis | last=Campbell | accessdate=2010-04-07}}</ref> | |||

| ] is associated with a type of dementia called ], which is caused by a deficiency in ] (vitamin B<sub>1</sub>).<ref name="Oscar-Berman2003"/> | |||

| In people aged 55 or older, daily light-to-moderate drinking (one to three drinks) was associated with a 42% reduction in the probability of developing dementia and a 70% reduction in risk of ].<ref name="olddementia">{{Cite news|publisher=BBC News|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1780130.stm|date=2002-01-25|title=Alcohol 'could reduce dementia risk'}}</ref> The researchers suggest that alcohol may stimulate the release of ] in the ] area of the brain.<ref name="olddementia"/> | |||

| =====Diabetes===== | |||

| If both parents have type 2 diabetes, this increases to a 45 percent chance.<ref>http://health.usnews.com/health-conditions/diabetes/type-2-diabetes</ref> | |||

| =====Hip fracture===== | |||

| An international study<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kanis JA |title=Alcohol intake as a risk factor for fracture |journal=Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA |volume=16 |issue=7 |pages=737–42 |year=2005 |month=July |pmid=15455194 |doi=10.1007/s00198-004-1734-y |url= |author-separator=, |author2=Johansson H |author3=Johnell O |display-authors=3 |last4=Oden |first4=Anders |last5=Laet |first5=Chris |last6=Eisman |first6=John A. |last7=Pols |first7=Huibert |last8=Tenenhouse |first8=Alan}}</ref> of almost 6,000 men and 11,000 women found that persons who reported that they drank more than 2 units of alcohol a day had an increased risk of fractures compared to non-drinkers. For example, those who drank over 3 units a day had nearly twice the risk of a hip fracture. | |||

| =====Obesity===== | |||

| Biological and environmental factors are thought to contribute to alcoholism and obesity.<ref name="Alcohol Studies 2003">UNC Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies. Alcoholism and Obesity: Overlapping Brain Pathways? Center Line. Vol 14, 2003.</ref> The physiologic commonalities between excessive eating and excessive alcohol drinking shed light on intervention strategies, such as pharmaceutical compounds that may help those who suffer from both. | |||

| Some of the brain signaling proteins that mediate excessive eating and weight gain also mediate uncontrolled alcohol consumption.<ref name="Alcohol Studies 2003"/> Some physiological substrates that underlie food intake and alcohol intake have been identified. Melanocortins, a group of signaling proteins, are found to be involved in both excessive food intake and alcohol intake.<ref>Thiele et al. Overlapping Peptide Control of Alcohol Self-Administration and Feeding. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, Vol 28, No 2, 2004: pp 288–294.</ref> | |||

| Alcohol may contribute to obesity. A study found frequent, light drinkers (three to seven drinking days per week, one drink per drinking day) had lower BMIs than infrequent, but heavier drinkers.<ref name="Breslow 2001">Breslow et al. Drinking Patterns and Body Mass Index in Never Smokers: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2001. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:368–376.</ref> Although calories in liquids containing ethanol may fail to trigger the physiologic mechanism that produces the feeling of fullness in the short term; long-term, frequent drinkers may compensate for energy derived from ethanol by eating less.<ref name="ReferenceA">Cordain et al. Influence of moderate daily wine consumption on body weight regulation and metabolism in healthy free-living males. J Am Coll Nutr 1997;16:134–9.</ref> | |||

| ====Health effects of moderate drinking==== | |||

| {{See also|Moderation}} | |||

| =====Longevity===== | |||

| A meta-analysis found with data from 477,200 individuals determined the dose-response relationships by sex and end point using lifetime abstainers as the reference group. The search revealed 20 cohort studies that met our inclusion criteria. A U-shaped relationship was found for both sexes. Compared with lifetime abstainers, the relative risk (RR) for type 2 diabetes among men was most protective when consuming 22 g/day alcohol (RR 0.87 ) and became deleterious at just over 60 g/day alcohol (1.01 ). Among women, consumption of 24 g/day alcohol was most protective (0.60 ) and became deleterious at about 50 g/day alcohol (1.02 ).<ref name="autogenerated2">https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2768203/</ref> | |||

| Interestingly, ethanol has been found to double the lifespans of worms feed 0.005% ethanol but does not markedly increase at higher concentrations. Supplementing starved cultures with ''n''-propanol and ''n''-butanol also extended lifespan.;<!--<ref name="plosone.org"/>--> ] (''n''-propanol) is thought to be similar to ethanol in its effects on human body, but 2-4 times more potent. However, this seems to be statistically significant for humans when compared to the previous study discusses; Human macronutrients in food consist mainly of water and the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for water is 3.7 litres (3700 mL x 0.005% EtOH = 18.5 mL EtOH) for 19-70 year old males, and 2.7 litres (2700 mL x 0.005% EtOH = 13.5 mL) for 19-70 year old women. | |||

| Because former drinkers may be inspired to abstain due to health concerns, they may actually be at increased risk of developing diabetes, known as the sick-quitter effect. Moreover, the balance of risk of alcohol consumption on other diseases and health outcomes, even at moderate levels of consumption, may outweigh the positive benefits with regard to diabetes. | |||

| Additionally, the way in which alcohol is consumed (i.e., with meals or bingeing on weekends) affects various health outcomes. Thus, it may be the case that the risk of diabetes associated with heavy alcohol consumption is due to consumption mainly on the weekend as opposed to the same amount spread over a week.<ref name="autogenerated2"/> In the United Kingdom "advice on weekly consumption is avoided". | |||

| In a 2010 long-term study of an older population, the beneficial effects of moderate drinking were confirmed, but abstainers and heavy drinkers showed an increase of about 50% in ] (even after controlling for confounding factors).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Holahan |first1=Charles J. |last2=Schutte |first2=Kathleen K. |last3=Brennan |first3=Penny L. |last4=Holahan |first4=Carole K. |last5=Moos |first5=Bernice S. |last6=Moos |first6=Rudolf H. |title=Late-Life Alcohol Consumption and 20-Year Mortality |journal=Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research |volume=34 |issue=11 |pages=1961–71 |year=2010 <!--|doi=10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01286.x--> |pmid=20735372}}</ref> | |||

| =====Diabetes===== | |||

| Daily consumption of a small amount of pure ] by older women may slow or prevent the onset of diabetes by lowering the level of ].<ref name="diabetes">{{Cite news|publisher=BBC News|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1988884.stm|title=Alcohol may prevent diabetes|date=2002-05-15}}</ref> However, the researchers caution that the study used pure alcohol and that alcoholic beverages contain additives, including sugar, which would negate this effect.<ref name="diabetes"/> | |||

| People with diabetes should avoid sugary drinks such as ]s and ]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/ate/diabetes/201565.html|publisher=Net Doctor|author=Dr Roger Henderson, GP|date=2006-01-17|title=Alcohol and diabetes}}</ref> | |||

| =====Heart disease===== | |||

| {{Main|Alcohol and cardiovascular disease}} | |||

| Alcohol consumption by the elderly results in increased ], which is almost entirely a result of lowered coronary heart disease.<ref name="klat"/> A British study found that consumption of two ] (one regular glass of wine) daily by doctors aged 48+ years increased longevity by reducing the risk of death by ] and ].<ref name="mortal">{{Cite journal |last1=Doll |first1=R. |last2=Peto |first2=R |last3=Boreham |first3=J |last4=Sutherland |first4=I |title=Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors |journal=International Journal of Epidemiology |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=199–204 |year=2004 |pmid=15647313 |doi=10.1093/ije/dyh369}}</ref> Deaths for which alcohol consumption is known to increase risk accounted for only 5% of the total deaths, but this figure increased among those who drank more than two units of alcohol per day.<ref name="mortal"/> | |||

| One study found that men who drank moderate amounts of alcohol three or more times a week were up to 35% less likely to have a heart attack than non-drinkers, and men who increased their daily alcohol consumption by one drink over the 12 years of the study had a 22% lower risk of heart attack.<ref>{{Cite news|publisher=BBC News|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/2638399.stm|title=Frequent tipple cuts heart risk|date=2008-01-09}}</ref> | |||

| Daily intake of one or two ] (a half or full standard glass of wine) is associated with a lower risk of ] in men over 40, and in women who have been through menopause.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bhf.org.uk/keeping_your_heart_healthy/healthy_eating/alcohol_advice.aspx|publisher=]|title=Alcohol and heart disease}}</ref> However, getting drunk one or more times per month put women at a significantly increased risk of heart attack, negating alcohol's potential protective effect.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/05/070523153047.htm|title=Moderate Drinking Lowers Women's Risk Of Heart Attack|publisher=Science Daily|date=2007-05-25}}</ref> | |||

| Increased ] due to alcohol consumption is almost entirely the result of a reduced rate of coronary heart disease.<ref name="klat">{{cite journal |last1=Klatsky |first1=A L |last2=Friedman |first2=G D |title=Alcohol and longevity |journal=American Journal of Public Health |volume=85 |issue=1 |pages=16–8 |year=1995 |pmid=7832254 |pmc=1615277 |doi=10.2105/AJPH.85.1.16}}</ref> | |||

| =====Neurotoxin===== | |||

| {{see also|Neurotoxin}} | |||

| ] | |||

| As a neurotoxin, ethanol has been shown to induce nervous system damage and affect the body in a variety of ways. Among the known effects of ethanol exposure are both transient and lasting consequences. Some of the lasting effects include long-term reduced ] in the ],<ref>Taffe 2010</ref><ref>Morris 2009</ref> widespread brain atrophy,<ref>Bleich 2003</ref> and induced ] in the brain.<ref>Blanco 2005</ref> Of note, chronic ethanol ingestion has additionally been shown to induce reorganization of cellular membrane constituents, leading to a ] marked by increased membrane concentrations of ] and ].<ref name=Leonard1986>Leonard 1986</ref> This is important as neurotransmitter transport can be impaired through vesicular transport inhibition, resulting in diminished neural network function. One significant example of reduced inter-neuron communication is the ability for ethanol to inhibit ] in the hippocampus, resulting in reduced ] and memory acquisition.<ref name=Lovinger1989>Lovinger 1989</ref> NMDA has been shown to play an important role in long-term potentiation (LTP) and consequently memory formation.<ref>Davis 1992</ref> With chronic ethanol intake, however, the susceptibility of these NMDA receptors to induce LTP increases in the ] in an ] (IP3) dependent manner.<ref>Bernier 2011</ref> This reorganization may lead to neuronal cytotoxicity both through hyperactivation of postsynaptic neurons and through induced addiction to continuous ethanol consumption. It has, additionally, been shown that ethanol directly reduces intracellular calcium ion accumulation through inhibited NMDA receptor activity, and thus reduces the capacity for the occurrence of LTP.<ref name=Takadera1990>Takadera 1990</ref> | |||

| In addition to the neurotoxic effects of ethanol in mature organisms, chronic ingestion is capable of inducing severe developmental defects. Evidence was first shown in 1973 of a connection between chronic ethanol intake by mothers and defects in their offspring.<ref>Jones 1973</ref> This work was responsible for creating the classification of ]; a disease characterized by common ] aberrations such as defects in ] formation, limb development, and ] formation. The magnitude of ethanol neurotoxicity in ]es leading to fetal alcohol syndrome has been shown to be dependent on antioxidant levels in the brain such as ].<ref>Mitchell 1999</ref> As the fetal brain is relatively fragile and susceptible to induced stresses, severe deleterious effects of alcohol exposure can be seen in important areas such as the hippocampus and ]. The severity of these effects is directly dependent upon the amount and frequency of ethanol consumption by the mother, and the stage in development of the fetus.<ref>Gil-Mohapel 2010</ref> It is known that ethanol exposure results in reduced antioxidant levels, mitochondrial dysfunction (Chu 2007), and subsequent neuronal death, seemingly as a result of increased generation of ] (ROS).<ref name=Brocardo2011>Brocardo 2011</ref> This is a plausible mechanism, as there is a reduced presence in the fetal brain of antioxidant enzymes such as ] and ].<ref>Bergamini 2004</ref> In support of this mechanism, administration of high levels of ] vitamin E results in reduced or eliminated ethanol-induced neurotoxic effects in fetuses.<ref name=Heaton2000>Heaton 2000</ref> | |||

| =====Self-medication===== | |||

| Alcohol and sedative/hypnotic drugs, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines, are central nervous system (CNS) depressants, which produce feelings of relaxation, and sedation, while relieving feelings of depression and anxiety. Alcohol also lowers inhibitions, while benzodiazepines are anxiolytic. Though they are generally ineffective antidepressants, as most are short-acting, the rapid onset of alcohol and sedative/hypnotics softens rigid defenses and, in low to moderate doses, provides the illusion of relief from depressive affect and anxiety. As alcohol also lowers inhibitions, alcohol is also hypothesized to be used by those who normally constrain emotions by attenuating intense emotions in high or obliterating doses, which allows them to express feelings of affection, aggression, and closeness. | |||

| {{see also|Self-medication|}} | |||

| ;Anxiolytics/Antidepressant | |||

| ] and ]/] drugs, such as ] and ], are ] (CNS) ] that lower inhibitions via ]. Depressants produce feelings of relaxation and sedation, while relieving feelings of depression and anxiety. Though they are generally ineffective antidepressants, as most are short-acting, the rapid onset of alcohol and sedative/hypnotics softens rigid defenses and, in low to moderate doses, provides relief from depressive affect and anxiety.<ref name=Khantzian1997>Khantzian, E.J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of drug use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4, 231-244.</ref><ref name=Khantzian2003>Khantzian, E.J. (2003). The self-medication hypothesis revisited: The dually diagnosed patient. Primary Psychiatry, 10, 47-48, 53-54.</ref> As alcohol also lowers inhibitions, alcohol is also hypothesized to be used by those who normally constrain emotions by attenuating intense emotions in high or obliterating doses, which allows them to express feelings of affection, aggression and closeness.<ref name=Khantzian2003/><ref name=Khantzian1999 >Khantzian, E.J. (1999). Treating addiction as a human process. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.</ref> People with ] commonly use these drugs to overcome their highly set inhibitions.<ref>Sarah W. Book, M.D., and Carrie L. Randall, Ph.D. . Alcohol Research and Health, 2002.</ref> | |||

| Self medicating excessively for prolonged periods of time with benzodiazepines or alcohol often makes the symptoms of anxiety or depression worse. This is believed to occur as a result of the changes in brain chemistry from long-term use.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Professor C Heather Ashton |url=http://www.benzo.org.uk/ashbzoc.htm |year=1987 |title= Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: Outcome in 50 Patients |journal=British Journal of Addiction |volume=82 |pages=655–671}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Michelini S |coauthors=Cassano GB, Frare F, Perugi G |year=1996 |month=July |title=Long-term use of benzodiazepines: tolerance, dependence and clinical problems in anxiety and mood disorders |journal= Pharmacopsychiatry |volume=29 |issue=4 |pages=127–34 |pmid=8858711 |doi=10.1055/s-2007-979558}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Wetterling T |coauthors=Junghanns K |year=2000 |month=Dec |title=Psychopathology of alcoholics during withdrawal and early abstinence |journal=Eur Psychiatry |volume=15 |issue=8 |pages=483–8 |pmid=11175926 |doi=10.1016/S0924-9338(00)00519-8}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Cowley DS |date=Jan 1, 1992 |title=Alcohol abuse, substance abuse, and panic disorder |journal=Am J Med |volume=92 |issue=1A |pages=41S–8S |pmid=1346485 |doi=10.1016/0002-9343(92)90136-Y}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Cosci F |coauthors=Schruers KR, Abrams K, Griez EJ |year=2007 |month=Jun |title=Alcohol use disorders and panic disorder: a review of the evidence of a direct relationship |journal=J Clin Psychiatry |volume=68 |issue=6 |pages=874–80 |pmid=17592911 |doi=10.4088/JCP.v68n0608}}</ref> Of those who seek help from mental health services for conditions including ] such as ] or ], approximately half have alcohol or ] issues.<ref name=pmid7769598/> | |||

| Sometimes anxiety precedes alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence but the alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence acts to keep the anxiety disorders going, often progressively making them worse. However, some people addicted to alcohol or benzodiazepines, when it is explained to them that they have a choice between ongoing poor mental health or quitting and recovering from their symptoms, decide on quitting alcohol or benzodiazepines or both. It has been noted that every individual has an individual sensitivity level to alcohol or sedative hypnotic drugs, and what one person can tolerate without ill health, may cause another to suffer very ill health, and even moderate drinking can cause rebound anxiety syndrome and sleep disorders. A person suffering the toxic effects of alcohol will not benefit from other therapies or medications, as these do not address the root cause of the symptoms.<ref name=pmid7769598>{{cite journal |author=Cohen SI |title=Alcohol and benzodiazepines generate anxiety, panic and phobias |journal=J R Soc Med |volume=88 |issue=2 |pages=73–7 |year= 1995 |month=February |pmid=7769598 |pmc=1295099 }}</ref> | |||

| ;Insomnia | |||

| {{see also|Insomnia#Alcohol}} | |||

| Alcohol is often used as a form of self-treatment of insomnia to induce sleep. However, alcohol use to induce sleep can be a cause of insomnia. ] is associated with a decrease in ] stage 3 and 4 sleep as well as suppression of ] and REM sleep fragmentation. Frequent moving between sleep stages occurs, with awakenings due to headaches, ], ], and ]. Glutamine rebound also plays a role as when someone is drinking; alcohol inhibits glutamine, one of the body's natural stimulants. When the person stops drinking, the body tries to make up for lost time by producing more glutamine than it needs. | |||

| The increase in glutamine levels stimulates the brain while the drinker is trying to sleep, keeping him/her from reaching the deepest levels of sleep.<ref>Perry, Lacy. (2004-10-12) . Health.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-20.</ref> Stopping chronic alcohol use can also lead to severe insomnia with vivid dreams. During withdrawal REM sleep is typically exaggerated as part of a ].<ref name="sleep_medicine_a04">{{Cite book| last1 = Lee-chiong | first1 = Teofilo | title = Sleep Medicine: Essentials and Review | date = 24 April 2008 | publisher = Oxford University Press, USA | url = http://books.google.com/?id=s1F_DEbRNMcC&pg=PT105 | isbn = 0-19-530659-7 | page = 105 }}</ref> | |||

| =====Stroke===== | |||

| A study found that lifelong abstainers were 2.36 times more likely to suffer a ] than those who regularly drank a moderate amount of alcohol beverages. Heavy drinkers were 2.88 times more likely to suffer a stroke than moderate drinkers.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rodgers |first1=H |last2=Aitken |first2=PD |last3=French |first3=JM |last4=Curless |first4=RH |last5=Bates |first5=D |last6=James |first6=OF |title=Alcohol and stroke. A case-control study of drinking habits past and present. |url=http://stroke.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=8378949 |journal=Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation |volume=24 |issue=10 |pages=1473–7 |year=1993 |pmid=8378949}}</ref> | |||

Revision as of 01:01, 18 February 2013

Alcohol and health

See also: Template:Alcohol and healthShort-term effects of alcohol consumption include intoxication and dehydration. Long-term effects of alcohol include changes in the metabolism of the liver and brain and alcoholism (addiction to alcohol).

Alcohol intoxication affects the brain, causing slurred speech, clumsiness, and delayed reflexes. Alcohol stimulates insulin production, which speeds up glucose metabolism and can result in low blood sugar, causing irritability and (for diabetics) possible death. Severe alcohol poisoning can be fatal.

A blood alcohol content of 0.45% in test animals results in a median lethal dose of LD50. This means that 0.45% is the concentration of blood alcohol that is fatal in 50% of the test subjects. That is about six times the level of ordinary intoxication (0.08%), but vomiting or unconsciousness may occur much sooner in people who have a low tolerance for alcohol. The high tolerance of chronic heavy drinkers may allow some of them to remain conscious at levels above 0.40%, although serious health dangers are incurred at this level.

Alcohol also limits the production of vasopressin (ADH) from the hypothalamus and the secretion of this hormone from the posterior pituitary gland. This is what causes severe dehydration when large amounts of alcohol are drunk. It also causes a high concentration of water in the urine and vomit and the intense thirst that goes along with a hangover.

Stress, hangovers and oral contraceptive pill may increase the desire for alcohol because these things will lower the level of testosterone and alcohol will acutely elevate it. Tobacco has the same effect of increasing the craving for alcohol.

Abuse prevention

See also: Substance abuse preventionAlcohol abuse prevention programs

See also: Prevention Science0-1-2-3

The Army at Fort Drum has taken the “0-0-1-3” and exchanged it for the new “0-1-2-3” described in the Prime-For-Life Program, which highlights the ill effects of alcohol abuse as more than just an individual’s “driving while intoxicated.” The Prime-For-Life program identifies alcohol abuse to be a health and impairment problem, leading to adverse legal as well as health outcomes associated with misuse.

The 0-1-2-3 now represents low-risk guidelines:

- 0 – Zero drinks for those driving a vehicle.

- 1 – One drink per hour

- 2 – No more than two drinks per day

- 3 – Not to exceed three drinks on any one day

Recommended maximum intake

Main article: Recommended maximum intake of alcoholic beveragesBinge drinking is becoming a major problem in the UK. Advice on weekly consumption is avoided in United Kingdom.

Since 1995 the UK government has advised that regular consumption of 3–4 units a day for men, or 2–3 units a day for women, would not pose significant health risks, but that consistently drinking four or more units a day (men), or three or more units a day (women), is not advisable.

Previously (from 1992 until 1995), the advice was that men should drink no more than 21 units per week, and women no more than 14. (The difference between the sexes was due to the typically lower weight and water-to-body-mass ratio of women.) This was changed because a government study showed that many people were in effect "saving up" their units and using them at the end of the week, a phenomenon referred to as binge drinking. The Times reported in October 2007 that these limits had been "plucked out of the air" and had no scientific basis.

Sobriety

See also: Sobriety

Sobriety is the condition of not having any measurable levels, or effects from mood-altering drugs. According to WHO "Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms..." sobriety is continued abstinence from psychoactive drug use. Sobriety is also considered to be the natural state of a human being given at a birth. In a treatment setting, sobriety is the achieved goal of independence from consuming or craving mind-altering substances. As such, sustained abstinence is a prerequisite for sobriety. Early in abstinence, residual effects of mind-altering substances can preclude sobriety. These effects are labeled "PAWS", or "post acute withdrawal syndrome". Someone who abstains, but has a latent desire to resume use, is not considered truly sober. An abstainer may be subconsciously motivated to resume drug use, but for a variety of reasons, abstains (e.g. such as a medical or legal concern precluding use). Sobriety has more specific meanings within specific contexts, such as the culture of Alcoholics Anonymous, other 12 step programs, law enforcement, and some schools of psychology. In some cases, sobriety implies achieving "life balance."

Mortality rate

Main article: Long-term effects of alcohol § Alcohol-related deathsA report of the United States Centers for Disease Control estimated that medium and high consumption of alcohol led to 75,754 deaths in the U.S. in 2001. Low consumption of alcohol had some beneficial effects, so a net 59,180 deaths were attributed to alcohol.

In the United Kingdom, heavy drinking is blamed for about 33,000 deaths a year.

A study in Sweden found that 29% to 44% of "unnatural" deaths (those not caused by illness) were related to alcohol. The causes of death included murder, suicide, falls, traffic accidents, asphyxia, and intoxication.

A global study found that 3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are caused by alcohol drinking, resulting in 3.5% of all global cancer deaths. A study in the United Kingdom found that alcohol causes about 6% of cancer deaths in the UK (9,000 deaths per year).

ISCD

A 2010 study by the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, led by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, asked drug-harm experts to rank a selection of illegal and legal drugs on various measures of harm both to the user and to others in society. These measures include damage to health, drug dependency, economic costs and crime. The researchers claim that the rankings are stable because they are based on so many different measures and would require significant discoveries about these drugs to affect the rankings.

Despite being legal more often than the other drugs, alcohol was considered to be by far the most harmful; not only was it regarded as the most damaging to societies, it was also seen as the fourth most dangerous for the user. Most of the drugs were rated significantly less harmful than alcohol, with most of the harm befalling the user.

The authors explain that one of the limitation of this study is that drug harms are functions of their availability and legal status in the UK, and so other cultures' control systems could yield different rankings.

Alcohol expectations

Alcohol expectations are beliefs and attitudes that people have about the effects they will experience when drinking alcoholic beverages. They are largely beliefs about alcohol's effects on a person’s behaviors, abilities, and emotions. Some people believe that if alcohol expectations can be changed, then alcohol abuse might be reduced.

The phenomenon of alcohol expectations recognizes that intoxication has real physiological consequences that alter a drinker's perception of space and time, reduce psychomotor skills, and disrupt equilibrium. The manner and degree to which alcohol expectations interact with the physiological short-term effects of alcohol, resulting in specific behaviors, is unclear.

A single study found, if a society believes that intoxication leads to sexual behavior, rowdy behavior, or aggression, then people tend to act that way when intoxicated. But if a society believes that intoxication leads to relaxation and tranquil behavior, then it usually leads to those outcomes. Alcohol expectations vary within a society, so these outcomes are not certain.

People tend to conform to social expectations, and some societies expect that drinking alcohol will cause disinhibition. However, in societies in which the people do not expect that alcohol will disinhibit, intoxication seldom leads to disinhibition and bad behavior.

Alcohol expectations can operate in the absence of actual consumption of alcohol. Research in the United States over a period of decades has shown that men tend to become more sexually aroused when they think they have been drinking alcohol, — even when they have not been drinking it. Women report feeling more sexually aroused when they falsely believe the beverages they have been drinking contained alcohol (although one measure of their physiological arousal shows that they became less aroused).

Men tend to become more aggressive in laboratory studies in which they are drinking only tonic water but believe that it contains alcohol. They also become less aggressive when they believe they are drinking only tonic water, but are actually drinking tonic water that contains alcohol.

Genetic differences

Alcohol flush reaction

See also: Alcohol flush reactionAlcohol flush reaction is best known as a condition that is experienced by people of Asian descent. According to the analysis by HapMap project, the rs671 allele of the ALDH2 gene responsible for the flush reaction is rare among Europeans and Africans, and it is very rare among Mexican-Americans. 30% to 50% of people of Chinese and Japanese ancestry have at least one ALDH*2 allele. The rs671 form of ALDH2, which accounts for most incidents of alcohol flush reaction worldwide, is native to East Asia and most common in southeastern China. It most likely originated among Han Chinese in central China, and it appears to have been positively selected in the past. Another analysis correlates the rise and spread of rice cultivation in Southern China with the spread of the allele. The reasons for this positive selection aren't known, but it's been hypothesized that elevated concentrations of acetaldehyde may have conferred protection against certain parasitic infections, such as Entamoeba histolytica.

American Indian alcoholism

See also: American Indian alcoholismWhile little detailed genetic research has been done, it has been shown that alcoholism tends to run in families with possible involvement of differences in alcohol metabolism and the genotype of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes.

Gender differences

Sensitivity

Several biological factors make women more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol than men.

- Body fat. Women tend to weigh less than men, and—pound for pound—a woman’s body contains less water and more fatty tissue than a man’s. Because fat retains alcohol while water dilutes it, alcohol remains at higher concentrations for longer periods of time in a woman’s body, exposing her brain and other organs to more alcohol.

- Enzymes. Women have lower levels of two enzymes—alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase—that metabolize (break down) alcohol in the stomach and liver. As a result, women absorb more alcohol into their bloodstreams than men.

- Hormones. Changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle may also affect how a woman metabolizes alcohol.

Metabolism

Females demonstrated a higher average rate of elimination (mean, 0.017; range, 0.014-0.021 g/210 L) than males (mean, 0.015; range, 0.013-0.017 g/210 L). Female subjects on average had a higher percentage of body fat (mean, 26.0; range, 16.7-36.8%) than males (mean, 18.0; range, 10.2-25.3%).

Depression

The link between alcohol consumption, depression, and gender was examined by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada). The study found that women taking antidepressants consumed more alcohol than women who did not experience depression as well as men taking antidepressants. The researchers, Dr. Kathryn Graham and a PhD Student Agnes Massak analyzed the responses to a survey by 14,063 Canadian residents aged 18–76 years. The survey included measures of quantity, frequency of drinking, depression and antidepressants use, over the period of a year. The researchers used data from the GENACIS Canada survey, part of an international collaboration to investigate the influence of cultural variation on gender differences in alcohol use and related problems. The purpose of the study was to examine whether, like in other studies already conducted on male depression and alcohol consumption, depressed women also consumed less alcohol when taking anti-depressants. According to the study, both men and women experiencing depression (but not on anti-depressants) drank more than non-depressed counterparts. Men taking antidepressants consumed significantly less alcohol than depressed men who did not use antidepressants. Non-depressed men consumed 436 drinks per year, compared to 579 drinks for depressed men not using antidepressants, and 414 drinks for depressed men who used antidepressants. Alcohol consumption remained higher whether the depressed women were taking anti-depressants or not. 179 drinks per year for non-depressed women, 235 drinks for depressed women not using antidepressants, and 264 drinks for depressed women who used antidepressants. The lead researcher argued that the study "suggests that the use of antidepressants is associated with lower alcohol consumption among men suffering from depression. But this does not appear to be true for women."

Short-term effects of alcohol

See also: Alcohol and sex, Blood alcohol content, Alcohol intoxication, and Short-term effects of alcoholBlood ethanol concentration (BEC)

See also: Blood alcohol content

Vehicle operation

The number of serious errors committed by pilots dramatically increases at or above concentrations of 0.04% blood alcohol. This is not to say that problems don't occur below this value. Some studies have shown decrements in pilot performance with blood alcohol concentrations as low as the 0.025%. Also, a BEC of ≥0.080 or more is legally intoxicated for driving in MOST states. And, ≤0.050 is considered NOT impaired in most.

Estimated blood ethanol concentration (EBAC)

In order to calculate estimated peak blood alcohol concentration (EBAC) a variation, including drinking period in hours, of the Widmark formula was used. The formula is: