| Revision as of 05:24, 7 March 2012 view sourceRjensen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers227,463 edits →Further reading: add cites← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:02, 30 March 2012 view source Ealdgyth (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators153,204 editsm (auto: 19 en dash; 2 ref)Next edit → | ||

| (244 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Other uses}} | {{Other uses}} | ||

| {{Redirect2|Medieval|Mediaeval}} | {{Redirect2|Medieval|Mediaeval}} | ||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

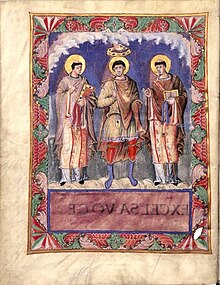

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}}] with popes ] and ]]] | |||

| ], which was a burial of an ] warrior during the ].|thumb|right|300px|upright]] | |||

| ]s, such as ] which was built by Crusaders, were a prominent feature of the medieval period.]] | |||

| The '''Middle Ages''' (adjectival form: '''medieval''', '''mediaeval''' or '''mediæval''') is a ] of ], encompassing the period from the ] to the ]. The Middle Ages follows the ] in 476 and precedes the ]. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: ], Medieval and ]. The term "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in the 15th century and reflects the view that this period was a deviation from the path of classical learning, a path that was later reconnected by ] scholarship. | |||

| The '''Middle Ages''' (adjectival form: '''medieval''', '''mediaeval''' or '''mediæval''') is a ] of ], encompassing the period from the ] to the ]. Historians traditionally mark the beginning of the Middle Ages with the ] in 476 and the end with the ] in 1453. It is followed by the ] and is the middle period of the traditional three-period division of Western history into ], Medieval and ]. | |||

| In the ] the trends of the ] (depopulation, deurbanization, and increased ] invasion) continued. ] and the ], once part of the ], became ]. Later in the period, the establishment of the ] allowed a move away from ]. There was sustained ] in ] and ]. | |||

| In the ] depopulation, deurbanization, and ] invasion, all of which had begun in ], continued and strengthened. The barbarian invaders formed their own new kingdoms in the remains of the ], while the ] survived and even expanded during the 6th century. In the 7th century ] and the ], once part of the eastern empire, became ] after conquest by ]'s successors. Although there was a large amount of change in society and political structures, the break was not as extreme as once put forth by historians, with many of the new kingdoms incorporating as many of the existing Roman institutions as they were able to. Christianity expanded in western Europe and monasteries were founded. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the ] under the ] established an empire that covered much of Western Europe, but this empire broke up in the 9th century under pressures from new invaders. | |||

| During the ] (c. 1000–1300), ]-oriented ] and ] flourished and ] were mounted to recapture the ] from ] control. The influence of the emerging ] was tempered by the ideal of an international ]. The codes of ] and ] set rules for proper behavior, while the ] ]s attempted to reconcile faith and reason. Outstanding achievement in this period includes the ], the mathematics of ] and ], the philosophy of ], the paintings of ], the poetry of ] and ], the travels of ], and the architecture of ] cathedrals such as ]. | |||

| During the ] which began after 1000, the population of Europe grew greatly as new technological and agricultural inventions allowed trade to flourish and crop yields to increase. ] - the organization of peasants into villages which owed rents and labor service to nobles - and ] - a political structure whereby ]s and lower status nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rents from lands and ]s - were two of the ways of organizing medieval society that developed during the High Middle Ages. Kingdoms became more centralized after the decentralizing effects of the breakup of the ]. The ], which were first preached in 1095, were an attempt by western Christians to regain control of the ] from the ], and succeeded long enough to found some Christian kingdoms in and around Jerusalem. ] and the founding of universities marked intellectual life, while the building of ] was one of the outstanding achievements of artistic life. | |||

| The ] were marked by difficulties and calamities. Famine, plague and war decimated the population of western Europe, with the ] alone killing approximately a third of the population between the years 1347 and 1350. Controversy and ] within the Church was echoed by warfare between states as well as civil war and peasant revolts inside kingdoms. Heresies developed and added to difficulties within the Church. | |||

| ==Etymology and periodization== | ==Etymology and periodization== | ||

| {{see also|Periodization}} | {{see also|Periodization}} | ||

| The Middle Ages is one of the three major periods in the most enduring scheme for analyzing ]: classical civilization (or ]), the Middle Ages, and the ].<ref name= |

The Middle Ages is one of the three major periods in the most enduring scheme for analyzing ]: classical civilization (or ]), the Middle Ages, and the ].<ref name=Power304>Power ''Central Middle Ages'' p. 304</ref> It is "middle" in the sense of being between the two other periods in time. ]s in the Renaissance argued that their scholarship restored direct links to the classical period, thus bypassing the Medieval period. The "Middle Ages" first appears in Latin in 1469 as ''media tempestas'' (middle times).<ref name=Albrow205>Albrow ''Gllobal Age'' p. 205</ref> In early usage, there were many variants, including ''medium aevum'' (Middle Age), first recorded in 1604,<ref name=Albrow205/> and ''media scecula'' (Middle Ages), first recorded in 1625.<ref name=Robinson>Robinson "" ''Speculum''</ref> English is the only major language that retains the plural form.<ref name=Robinson/> | ||

| ] was a Renaissance historian who helped develop the concept of the Middle Ages.]] | |||

| ===Development of concept=== | |||

| Medieval historians did not think of themselves as being in the middle of history. Instead, they wrote history from a ] and theological perspective. They divided history into periods such as the "]" or the "]", with their period being the last before the end of the world. They considered the Roman period, especially the time of the ], an historical peak, followed by a long slide toward the ].<ref name="idea">""</ref> | |||

| In the 1330s, the humanist and poet ] referred to pre-Christian times as ''antiqua'' (ancient) and to the Christian period as ''nova'' (new).<ref name="idea"/> While retaining the theme of decline from the apogee of ancient Rome, Petrarch's division was not based on theology, but on a perception of cultural and political decline, especially the idea that Medieval Latin was inferior to Classical Latin.<ref name=mommsen>{{cite journal | last = Mommsen | first = Theodore |authorlink =Theodor Mommsen | coauthors = | title = Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages' | journal = ] | volume = 17 | issue = 2 | pages = 226–242 |publisher = ] | location = Cambridge MA | year = 1942 | jstor = 2856364| doi = 10.2307/2856364}}</ref> From Petrarch's Italian perspective, this new period (which included his own time) was an age of national eclipse.<ref name=mommsen/> | |||

| ] was the first historian to use ] in his ''History of the Florentine People'' (1442).<ref name="Hankins">Leonardo Bruni, James Hankins, ''History of the Florentine people'', Volume 1, Books 1–4, (2001), p. xvii.</ref> Bruni's first two periods were based on those of Petrarch, but he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. ] used a similar framework in ''Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire'' (1439–1453). Tripartite periodization became standard after the German historian ] published ''Universal History Divided into an Ancient, Medieval, and New Period'' (1683). | |||

| ===Start and end dates=== | ===Start and end dates=== | ||

| The most commonly given start date for the Middle Ages is 476,<ref>"" |

The most commonly given start date for the Middle Ages is 476,<ref>"" Dictionary.com</ref> first used by Bruni.<ref name=Hankins>Bruni ''History of the Florentine people'' p. xvii</ref> For Europe as a whole, date of 1500 is often used for the ending of the Middle Ages as a whole.<ref>See the title of Watts ''Making of Polities Europe 1300–1500'' or Epstein ''Economic History of Later Medieval Europe 1000–1500''</ref> In contrast, English historians often use the ] (1485) to mark the end of the period.<ref>See the title of Saul ''Companion to Medieval England 1066–1485''</ref> For Spain, the death of King ] (1516), of Queen ] (1504) or otherwise the conquest of Granada (1492) is often used.<ref>Kamen ''Spain 1469–1714'' p. 29</ref> | ||

| ], England's last Medieval monarch]] | |||

| For Europe as a whole, the ] by the Turks in 1453 is commonly used as the end date of the Middle Ages. Depending on the context, other events, such as the invention of the ] printing press by ] c. 1455, the fall of ] in Spain or ]'s voyage to ] (both 1492), can be used. For Italy, 1401, the year the contract was awarded to build the north doors of the ], is often used.{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} In contrast, English historians often use the ] (1485) to mark the end of the period.<ref>Prudames, David. , 20 January 2005.</ref> For Spain, the death of King ] (1516), of Queen ] (1504) or otherwise the conquest of Granada (1492) is often used.<ref>Henry Kamen. ''Spain 1469–1714''. 2005. p. 29. ISBN 0-582-78464-6.</ref> | |||

| ===Subdivisions=== | ===Subdivisions=== | ||

| Historians in the Romance languages tend to divide the Middle Ages into two parts: an earlier " |

Historians in the Romance languages tend to divide the Middle Ages into two parts: an earlier "High" and later "Low" period. English-speaking historians, following their German counterparts, generally subdivide the Middle Ages into three intervals: "Early", "High" and "Late".<ref name=Power304/> Belgian historian ] and Dutch historian ] popularized the following subdivisions in the early 20th century: the ] (476–1000), the ] (1000–1300), and the ] (1300–1453). In the 19th century, the entire Middle Ages were often referred to as the "]".<ref name=mommsen>Mommsen "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" '']''</ref>{{efn|A reference work published in 1883 equates the Dark Ages with the Middle Ages, but beginning with ] in 1904, the term "Dark Ages" is generally restricted to the early part of the Medieval period. For example, the 1911 edition of ''Britannica'' defines the Dark Ages this way. See ] for a more complete historiography of this term.}} But with the creation of these subdivisions use of this term was restricted to the Early Middle Ages, at least among historians.<ref name=mommsen/> | ||

| ===Timeline=== | ===Timeline=== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 62: | ||

| ==The later Roman Empire== | ==The later Roman Empire== | ||

| {{main|Late Antiquity|Decline of the Roman Empire|Migration Period|Byzantine Empire}} | {{main|Late Antiquity|Decline of the Roman Empire|Migration Period|Byzantine Empire}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| The Roman empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century with the following two centuries witnessing the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories. |

The Roman empire reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century AD with the following two centuries witnessing the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories.<ref name=Cunliffe391>Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 391–393</ref> Economic issues, including inflation, and external pressures on the frontiers combined to make the 3rd century unstable politically, with a number of different emperors coming to the throne and then being replaced by new usurpers.<ref name=Collins3>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 3–5</ref> Military expenses increased steadily during the 3rd century, mainly in response to the need to defend against the ] with ], which began in the middle of the 3rd century. The need for revenue led to increased taxes and a decline in the number the ] landowning class, with increasing numbers of the members of that class being unwilling to shoulder the burdens of office holding in their native towns.<ref name=Heather111>Heather ''Fall of the Roman Empire'' p. 111</ref> | ||

| ], now located in Venice.|250px]] | |||

| Military expenses increased steadily during the 4th century, even as Rome's neighbours became restless and increasingly powerful. Tribes who previously had contact with the Romans as trading partners, rivals, or mercenaries had sought entrance to the empire and access to its wealth throughout the 4th century. | |||

| In the late 3rd and early 4th century, the Emperor ] split the empire into separately administered eastern and western halves in 286, although the empire was not considered divided, as legal and administrative promulgations in one division were considered valid in the other.<ref name=Collins9>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 9</ref>{{efn|This system, which eventually encompassed two senior co-emperors and two junior co-emperors, is known as the ].<ref name=Collins9/>}} After a period of civil war, in 330 Constantine refounded the city of ] as the newly renamed eastern capital, ].<ref name=Collins24>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 24</ref> Diocletian's reforms created a strong governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army. These reforms bought the Empire time, but did not completely solve the problems the empire was facing, which included excessive taxation, a declining birthrate, and pressures on the frontiers.<ref name=Cunliffe405>Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 405–406</ref> Civil war between different emperors became common in the middle of the 4th century, and the need for military forces to fight against rival emperors led to a weakening of frontier forces, with barbarian forces penetrating past the frontiers.<ref name=Collins31>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 31–33</ref> | |||

| ]|300px]] | |||

| Diocletian's reforms had created a strong governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army.<ref name="Treadgold">{{cite book|title= A History of the Byzantine State and Society|author=Treadgold, Warren|year= 1997|publisher=Stanford University Press|isbn=0804726302|edition=first}}</ref> These reforms bought the Empire time, but they demanded money. Roman power had been maintained by its well-trained and equipped armies. These armies, however, were a constant drain on the Empire's finances. As warfare became more dependent on ], the infantry-based Roman military started to lose its advantage against its rivals. The defeat in 378 at the ], at the hands of mounted Gothic lancers, destroyed much of the Roman army and left the ] undefended.<ref name="Treadgold"/> Without a strong army, the empire was forced to accommodate the large numbers of ] who sought refuge within its frontiers. | |||

| In 376, the ], fleeing from the ], received permission from the Roman emperor ] to settle in the Roman province of Thracia. But the settlement did not go smoothly, and when Roman officials mishandled the situation, they began to raid and plunder Thracia. Valens, attempting to put down the disorder, was killed in battle with the ] at the ] on 9 August 378.<ref name=Bauer47>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 47–49</ref> Besides the barbarian threat from the north, internal divisions within the empire, especially within the Christian Church, caused troubles.<ref name=Bauer56>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 56–59</ref> In 400, the ], invaded the western empire, and although briefly forced back from Italy, in 410 they were able to sack the city of Rome.<ref name=Bauer80>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 80–83</ref> While the Visigoths were invading, in 406 the ], ], and ] crossed into Gaul and over the next three years, they crossed across Gaul and in 409 arrived across the ] into modern-day Spain.<ref name=Collins59>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 59–60</ref> Other groups of barbarians took part in the movements of peoples in this time period. The ], ], and the ] eventually all ended up in northern Gaul while the ], ], and ] settled in Britain.<ref name=Cunliffe417/> In the 430s, the ] were added to the mix, with their king ] leading invasions into the Balkans in 442 and 447, into Gaul in 451, and into Italy in 452.<ref name=James67>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 67–68</ref> With Attila's death in 453, the Hunnic confederation he led fell apart.<ref name=Bauer117>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 117–118</ref> All of these invasions by the varied tribes totally redid the political and demographic face of what had been the western Roman empire.<ref name=Cunliffe417>Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' p. 417</ref> | |||

| By the end of the 5th century, the western empire was divided into smaller political units ruled by the tribes that had invaded in the early part of the century.<ref name=Wickham79>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 79</ref> The last emperor of the west, ], was deposed in 476, making this year the traditional date of the ending of the western empire.{{efn|An alternate date of 480 is sometimes given, as that was the date when Romulus Augustulus' predecessor ] died. Nepos had continued to assert that he was the western emperor while holding onto ].<ref name=Wickham86/>}}<ref name=Wickham86>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 86</ref> The ] (conventionally referred to as the "]" after the fall of its western counterpart) had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. Even though ] maintained a claim over the territory, and no "barbarian" king dared to elevate himself to the position of Emperor of the West, Byzantine control of most of the West could not be sustained; the ''renovatio imperii'' ("imperial restoration", entailing reconquest of the ] and Mediterranean periphery) by ] was the sole, and temporary, exception.<ref name=Collins116>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 116–134</ref> | |||

| Known in traditional historiography collectively as the "barbarian invasions", the ], or the ''Völkerwanderung'' ("wandering of the peoples"), this migration was a complicated and gradual process. Some of these "barbarian" tribes rejected the ], while others admired and aspired to emulate it. In return for land to farm and, in some regions, the right to collect ]s for the state, ] provided military support to the empire. Other incursions were small-scale military invasions of tribal groups assembled to gather plunder. The ], ], ], and ] all raided the Empire's territories and terrorised its inhabitants. Later, ] and Germanic peoples would settle the lands previously taken by these tribes. The most famous invasion culminated in the ] by the ] in 410, the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to an enemy. | |||

| By the end of the 5th century, Roman institutions were crumbling. Some early historians have given this period of ] the epithet of "]" because of the contrast to earlier times, (however, the term is avoided by current historians). The last emperor of the west, ], was deposed by the barbarian king ] in 476.<ref name="Treadgold"/> The ] (conventionally referred to as the "]" after the fall of its western counterpart) had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. Even though ] maintained a claim over the territory, and no "barbarian" king dared to elevate himself to the position of Emperor of the West, Byzantine control of most of the West could not be sustained; the ''renovatio imperii'' ("imperial restoration", entailing reconquest of the ] and Mediterranean periphery) by ] was the sole, and temporary, exception. | |||

| As Roman authority disappeared in the West, cities, literacy, trading networks and urban infrastructure declined. Where civic functions and infrastructure were maintained, it was mainly by the Christian Church. ] is an example of one ] who became a capable civic administrator. | |||

| ==Early Middle Ages== | ==Early Middle Ages== | ||

| {{main|Early Middle Ages}} | {{main|Early Middle Ages}} | ||

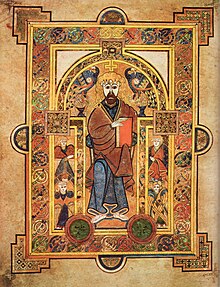

| ] is one of the most famous artworks of the Early Middle Ages.]] | |||

| === |

===New societies=== | ||

| The breakdown of Roman society was dramatic. The patchwork of petty rulers was incapable of supporting the depth of civic infrastructure required to maintain libraries, public baths, arenas, and major educational institutions. Any new building was on a far smaller scale than before. The social effects of the fracture of the Roman state were manifold. Cities and merchants lost the economic benefits of safe conditions for trade and manufacture, and intellectual development suffered from the loss of a unified cultural and educational milieu of far-ranging connections. | |||

| Although the political structure in western Europe had changed, the break was not as extensive as historians have claimed in the past. The emperors of the fifth century were often controlled by military men - such as ], ], ], or ] - and when western emperors ceased to be, many of the kings who replaced the emperor were from the same background as the military strongmen who had previously controlled the emperors. Intermarriage between the new kings and the Roman elites was common.<ref name=Wickham95>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 95–98</ref> This led to a fusion of the Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes, including the popular assemblies which led to a direct influence of more of the free male tribal members in political society.<ref name=Wickham100>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 100–101</ref> Material remains of the Romans and the invaders were often similar, with the tribal items often being obviously modeled on Roman items.<ref name=Collins100>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 100</ref> Similarly, much of the intellectual culture of the new kingdoms was directly based on Roman intellectual traditions.<ref name=Collins96>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 96–97</ref> An important difference, however, was the gradual loss of tax revenue by the new polities. Many of the new political entities no longer provided for their armies with tax revenues, but instead allocated lands or rents from lands to support the military forces. This change meant that there was less need for large tax revenues which meant that taxation systems decayed.<ref name=Wickham102>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 102–103</ref> Warfare was common between and within the kingdoms. Slavery declined as the supply declined and society became more rural.<ref name=Backman86>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 86–91</ref> | |||

| As it became unsafe to travel or carry goods over any distance, there was a collapse in trade and manufacture for export. The major industries that depended on long-distance trade, such as large-scale pottery manufacture, vanished almost overnight in places like Britain. Whereas sites like ] in ] (the extreme southwest of modern day England) had managed to obtain supplies of Mediterranean ]s well into the 6th century, this connection was now lost. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Between the 5th and 8th centuries, new peoples and powerful individuals filled the political void left by Roman centralized government. Germanic tribes established regional hegemonies within the former boundaries of the Empire, creating divided, decentralized kingdoms like those of the ] in ], the ] in ], the ] in ], the ] and ] in ] and Western ], the ] and the ] in ], and the ]s in ]. | |||

| Between the 5th and 8th centuries in western Europe, new peoples and powerful individuals filled the political void left by Roman centralized government.<ref name=Collins96/> The ] settled in ] in the late fifth century under ] and set up a kingdom marked by its cooperation between the Italians and the Ostrogoths, at least until the last years of Theodoric's reign.<ref name=James82>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 82–85</ref> The ] settled in ], and after an earlier kingdom was destroyed by the Huns in 436 they formed a new kingdom in the 440s between modern-day Geneva and Lyons. This grew to be a powerful kingdom in the late 5th and early 6th centuries.<ref name=James77>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 77–78</ref> In northern Gaul, the Franks and ], set up small kingdoms. The Frankish kingdom was centered in northeastern Gaul and the first king of whom much is known is ], who died in 481.{{efn|His grave was discovered in 1653 and is remarkable for the ] included, which included a number of weapons and a large quantity of gold.<ref name=James79>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 79–80</ref>}} Under Childeric's son Clovis, the Frankish kingdom expanded and converted to Christianity. The Britons, related to the natives of Britannia, settled in what is now Brittany, which took its name from their settlement.<ref name=James78>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 78–81</ref> Other kingdoms were established by the Visigoths in Spain, the Suevi in northwestern Spain, and the Vandals in North Africa.<ref name=James77/> In the 6th century, the ] settled in northern Italy, replacing the Ostrogothic kingdom with a grouping of duchies that occasionally selected a king to rule over all of them. By the late 6th century this arrangement had been replaced by a permanent monarchy.<ref name=Collins196>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 196–208</ref> | |||

| Roman landholders beyond the confines of ] were also vulnerable to extreme changes, and they could not simply pack up their land and move elsewhere. Some were dispossessed and fled to Byzantine regions; others quickly pledged their allegiances to their new rulers. In areas like Spain and Italy, this often meant little more than acknowledging a new overlord, while Roman forms of law and religion could be maintained. In other areas, where there was a greater weight of population movement, it might be necessary to adopt new modes of dress, language, and custom. | |||

| ===Byzantine survival=== | |||

| The ] of the 7th and 8th centuries of the ], ], ], ], ], ] eroded the area of the Roman Empire and controlled strategic areas of the Mediterranean. By the end of the 8th century, the former Western Roman Empire was decentralized and overwhelmingly rural. | |||

| ] surrounded by courtiers.|thumb|left]] | |||

| At the same time that western Europe was witnessing the formation of new kingdoms, the eastern section of the Empire remained intact and even enjoyed an economic revival that lasted into the early seventh century. There were less invasions of the eastern section of the empire, with most of those occurring in the Balkans. Peace with Persia, the traditional enemy of Rome, lasted throughout most of the 5th century. The eastern empire was marked by a much closer relationship between the political state and the Christian church, with doctrinal matters assuming an importance in eastern politics that they did not have in western Europe. Legal developments included the codification of ] known as the '']''.<ref name=Wickham81>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 81–83</ref> Under the emperor ] (reigned 527–565), a further compilation took place, known as the '']''.<ref name=Bauer200>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 200–202</ref> Justinian also oversaw the construction of the ] in Constantinople and the reconquest of North Africa from the Vandals and Italy from the Ostrogoths. But the conquest of Italy was not complete, and a deadly outbreak of plague in 542 meant that the rest of Justinian's reign was concentrated on defensive measures rather than further conquests.<ref name=Bauer206>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 206–213</ref> | |||

| A further complication for the eastern empire was the slow infiltration of the Balkans by the ], originally small invasions but by the late 540s Slavic tribes were in Thrace and Illyrium, defeating an imperial army near Adrianople in 551. In the 560s the ] began to expand from their base on the north bank of the ]. By the end of the 6th century they were the dominant power in Central Europe and were routinely able to force the eastern emperors to give them tribute. They remained a strong power until 796.<ref name=James95>James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 95–99</ref> Further complications were the involvement of the emperor ] in Persian politics when he intervened in a succession dispute. This led to a period of peace but when Maurice was overthrown in turn, the Persians invaded and during the reign of the emperor ] (reigned 610–641) managed to control large chunks of the empire, including Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor. Heraclius was eventually able to secure a peace treaty with the Persians in 628 that restored the earlier boundaries of the empire.<ref name=Collins140>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 140–143</ref> | |||

| ===Church and monasticism=== | |||

| ]. ] in England is an example of a ].]] | |||

| ===Religious ferment and Islam=== | |||

| The ], which means "universal church", was the major unifying cultural influence. It preserved selections from Latin learning, maintained the art of writing, and provided centralized administration through its network of ]s. Some regions that were populated by Catholics were conquered by ] rulers, which provoked much tension between Arian kings and the Catholic hierarchy. ] of the Franks is a well-known example of a barbarian king who chose Catholic orthodoxy over Arianism. His conversion marked a turning point for the Frankish tribes of Gaul. | |||

| {{main|Muslim conquests}} | |||

| Religious beliefs in the eastern empire and Persia were in flux during the late 6th and early 7th century. Judaism was an active missionary faith in this time period, with at least one Arab political leader converting to Judaism. Christianity also had active missions that competed with the Persian's Zoroastrianism in seeking to gain converts, especially amongst the residents of the Arabian peninsula. All of these strands came together in emergence of ] in Arabia during the lifetime of ].<ref name=Collins143>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 143–145</ref> After Muhammad's death in 632, Islamic forces went on to conquer much of the eastern Empire as well as Persia, starting with Syria in 634–635 and extending to Egypt in 640–641, Persia in between 637 and 642, North Africa in the later 7th century, and Spain in 711.<ref name=Collins149>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 149–151</ref> By the middle of the 8th century, new trading patterns were emerging in the Mediterranean, with trade between the Franks, the Arabs, and the Byzantines replacing the old Roman patterns of trade. Franks traded timber, furs, swords and slaves to the Arabs in return for silks and other fabrics, spices, and precious metals.<ref name=Cunliffe427>Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' pp. 427–428</ref> | |||

| Bishops were central to Middle Age society due to the literacy they possessed. As a result, they often played a significant role in governance. However, beyond the core areas of Western Europe, there remained many peoples with little or no contact with Christianity or with classical Roman culture. Martial societies such as the ] and the ] were still capable of causing major disruption to the newly emerging societies of Western Europe. | |||

| ===Church and monasticism=== | |||

| {{Main|History of the East–West Schism}} | |||

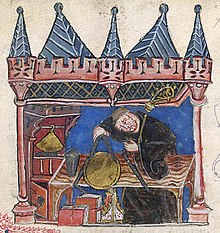

| ] dictating to a secretary.]] | |||

| Christianity was a major unifying factor between Eastern and Western Europe prior to the Arab conquests, but the conquest of North Africa sundered the connections. Increasingly, the Byzantine Church, which became the ], differed in language, practices, and liturgy from the western Church, which became the ]. The eastern church used Greek instead of the western Latin language. Theological and political differences emerged, and by the early and middle 8th century issues such as ], ], and state control of the church had widened enough that the cultural and religious differences were greater than the similarities.<ref name=Collins218>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 218–233</ref> | |||

| The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of ] within the West. Although the impulse to withdraw from society to focus upon a spiritual life is experienced by people of all cultures, the shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated in the deserts of Egypt and Syria.<ref name="Lawrence">{{cite book|title=Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages|author=Lawrence, C.H |publisher=Longman |edition=third |isbn=0582404274|year=2001}}</ref> The style of monasticism that focuses on community experience of the spiritual life, called ], was pioneered by the saint ] in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to Western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through ] such as the Life of ].<ref name="Lawrence"/> | |||

| The ecclesiastical structure of the Roman empire survived the barbarian invasions in the west mostly intact, but the papacy was little regarded, with few of the western bishops looking to the bishop of Rome for religious or political leadership. Many of the popes prior to 750 were more concerned with Byzantine affairs and eastern theological concerns. The register, or archive copies of the letters, of Pope ], (pope 590–604) survives, and of those more than 850 letters, the vast majority were concerned with affairs in Italy or Constantinople. The only part of western Europe where the papacy had influence was in Britain, where Gregory had sent the ] in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity.<ref name=WIckham170>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 170–172</ref> Other missionary efforts were led by the Irish, who between the 5th and the 7th centuries were the most active missionaries in wester Europe, with missionaries going first to England and Scotland and then later onto the continent. Irish missionaries, under such monks as ] and ], not only founded monasteries but also taught in both Latin and Greek and were active authors of both secular and religious works.<ref name=Colish62>Colish ''Medieval Foundations'' pp. 62–63</ref> | |||

| ] wrote the definitive ] for Western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an ].<ref name="Lawrence"/> The style of monasticism based upon the Benedictine Rule spread widely rapidly across Europe, replacing small clusters of cenobites. Monks and monasteries had a deep effect upon the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, bases for mission, and proselytization. In addition, they were the main and sometimes only outposts of education and literacy in a region. | |||

| The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of ] within the West. The shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated in the deserts of Egypt and Syria. The style of monasticism that focuses on community experience of the spiritual life, called ], was pioneered by the saint ] in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to Western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through ] such as the '']''.<ref name=Lawrence10>Lawrence ''Medieval Monasticism'' pp. 10–13</ref> ] wrote the ] for Western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an ].<ref name=Lawrence18>Lawrence ''Medieval Monasticism'' pp. 18–24</ref> Monks and monasteries had a deep effect upon the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, bases for mission, and proselytization.<ref name=Wickham185>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 185–187</ref> In addition, they were the main and sometimes only outposts of education and literacy in a region. Many of the surviving manuscripts of the Roman ] were copied in monasteries in the early Middle Ages.<ref name=Hamilton43>Hamilton ''Religion in the Medieval West'' pp. 43–44</ref> Monks were also the authors of new works, including history, theology, and other subjects, which were written by authors such as ], a native of northern England who wrote in the late 7th and early 8th century.<ref name=Colish64>Colish ''Medieval Foundations'' pp. 64–65</ref> | |||

| ===Carolingians=== | |||

| {{main|Frankish Empire|Carolingian Empire|Government of the Carolingian Empire}} | |||

| ] of Charlemagne depicted in the 14th-century ''Grandes Chroniques de France'']] | |||

| ===Carolingian Europe=== | |||

| A nucleus of power unfolded in a region of northern ] and developed into kingdoms called ] and ]. These kingdoms were ruled for three centuries by a dynasty of kings called the ], after their ] founder ]. The history of the Merovingian kingdoms is one of family politics that frequently erupted into civil warfare between the branches of the family. The legitimacy of the Merovingian throne was granted by a reverence for the bloodline, and, even after powerful members of the Austrasian court, the ], took de facto power during the 7th century, the Merovingians were kept as ceremonial figureheads. The Merovingians engaged in trade with northern Europe through ] ]s known to historians as the Northern Arc trade, and they are known to have minted small-denomination silver pennies called ] for circulation. Aspects of Merovingian culture could be described as "Romanized", such as the high value placed on ] as a symbol of rulership and the patronage of monasteries and ]. Some have hypothesized that the Merovingians were in contact with Byzantium. The Merovingians also buried the dead of their elite families in grave mounds and traced their lineage to a mythical sea beast called the ].<ref name="Wood">{{cite book|title=The Merovingian Kingdoms 450–751 |author=Wood, Ian |publisher=Pearson Education|year=1995|isbn=0582493722}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Frankish Empire|Carolingian Empire}} | |||

| ] with popes ] and ]]] | |||

| The Frankish kingdom in northern Gaul developed into kingdoms called ], ], and ] during the 6th and 7th centuries, under the ] who were descended from Clovis. The 7th century was a tumultuous period of ] between Austrasia and Neustria.<ref name=Bauer246>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 246–253</ref> Such warfare was exploited by ] the powerful Mayor of the Palace, who became the power behind the throne. Later members of his family line inherited the office, acting as advisors and regents. One of his descendents ] won the ] in 732, halting the advance of Muslim armies across the ].<ref name=Bauer347>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 347–349</ref> Muslim armies had earlier conquered the Visigothic kingdom of Spain, after defeating the last Visigothic king ] at the ] in 711, finishing the conquest by 719.<ref name=Bauer344>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' p. 344</ref> Across the English Channel in the British Isles, the island of Britain was divided into small states which were dominated by the kingdoms of ], ], ], and ], which were descended from the Anglo-Saxon invaders. Smaller kingdoms in present-day Wales and Scotland were still under the control of the original native British and Picts.<ref name=Wickham158>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 158–159</ref> Ireland was divided into even smaller political units, usually known as tribal kingdoms, which were under the control of kings. There were perhaps as many as 150 local kings in Ireland, of varying importance.<ref name=Wickham164>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 164–165</ref> | |||

| The 7th century was a tumultuous period of ] between Austrasia and Neustria. Such warfare was exploited by the patriarch of a family line, ], who curried favour with the Merovingians and had himself installed in the office of Mayor of the Palace at the service of the King. From this position of great influence, Pippin accrued wealth and supporters. Later members of his family line inherited the office, acting as advisors and regents. The dynasty took a new direction in 732, when ] won the ], halting the advance of Muslim armies across the ]. | |||

| The ] dynasty, as the successors to Charles Martel are known, officially took control of the kingdoms of Austrasia and Neustria in a coup of 753 led by ]. A contemporary chronicle claims that Pippin sought, and gained, authority for this coup from Pope ]. Pippin's takeover was reinforced with propaganda that portrayed the Merovingians as inept or cruel rulers and exalted the accomplishments of Charles Martel and circulated stories of the family's great piety. At the time of his death in 783, Pippin left his kingdom in the hands of his two sons, ] and ]. When Carloman died of natural causes, Charles blocked the succession of Carloman's minor son and installed himself as the king of the united Austrasia and Neustria. This Charles, known to his contemporaries as Charles the Great or ], embarked in 774 upon a program of systematic expansion that would unify a large portion of Europe, eventually controlling modern-day France, northern Italy, and Saxony. In the wars that lasted just beyond 800, he rewarded loyal allies with war booty and command over parcels of land.<ref name=Bauer371>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 371–378</ref> | |||

| ]s or ]s. Approximately 10-20% of the rural population of Carolingian Europe consisted of serfs and slaves.]] | |||

| The ] dynasty, as the successors to Charles Martel are known, officially took control of the kingdoms of Austrasia and Neustria in a coup of 753 led by ]. A contemporary chronicle claims that Pippin sought, and gained, authority for this coup from the Pope.<ref name="Riché">{{cite book|title=The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe |author=Riché, Pierre |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press|year=1993|isbn=0812213424}}</ref> Pippin's successful coup was reinforced with propaganda that portrayed the Merovingians as inept or cruel rulers and exalted the accomplishments of Charles Martel and circulated stories of the family's great piety. At the time of his death in 783, Pippin left his kingdoms in the hands of his two sons, ] and ]. When Carloman died of natural causes, Charles blocked the succession of Carloman's minor son and installed himself as the king of the united Austrasia and Neustria. This Charles, known to his contemporaries as Charles the Great or ], embarked in 774 upon a program of systematic expansion that would unify a large portion of Europe. In the wars that lasted just beyond 800, he rewarded loyal allies with war booty and command over parcels of land. Much of the nobility of the High Middle Ages was to claim its roots in the Carolingian nobility that was generated during this period of expansion.<ref name="Riché"/> | |||

| ] built 792/805 AD]] | ] built 792/805 AD]] | ||

| The coronation of Charlemagne as emperor on Christmas Day of 800 is regarded as a turning-point in medieval history, marking a return of the western Roman empire, since the new emperor ruled over much of the area previously controlled by the western emperors.<ref name=Backman109>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' p. 109</ref> It also marks a change in Charlemagne's relationship with the Byzantine empire, as the assumption of the imperial title by the Carolingians asserted their equivalency to the eastern empire.<ref name=Backman117>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 117–120</ref> However, there were a number of differences between the newly established Carolingian Empire and both the older western Roman empire and the concurrent Byzantine empire. The Frankish lands were rural in character, with few cities, and what cities existed were very small. Farming techniques were not advanced, and most of the people were peasants settled on small farms. Little trade existed and much of that was with the northern realms of the British Isles and Scandinavia, in contrast to the older Roman empire which had its trading networks centered on the Mediterranean.<ref name=Backman109/> | |||

| The Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas Day of 800 is frequently regarded as a turning-point in medieval history, because it filled a power vacancy that had existed since 476. It also marks a change in Charlemagne's leadership, which assumed a more imperial character and tackled difficult aspects of controlling an empire. He established a system of diplomats who possessed imperial authority, the ], who in theory provided access to imperial justice in the farthest corners of the empire.<ref>Although the ] makes appearances during the second half of the 8th century, it is after 800 that they were institutionalized. {{cite book|title=The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe|author=Riché, Pierre|publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press|year=1993|isbn=0812213424}}</ref> He also sought to reform the Church in his domains, pushing for uniformity in ] and material culture. | |||

| ===Carolingian Renaissance=== | ===Carolingian Renaissance=== | ||

| {{main|Carolingian Renaissance}} | {{main|Carolingian Renaissance}} | ||

| Charlemagne's court in ] was the centre of a cultural revival that is sometimes referred to as the "]". This period witnessed an increase of literacy, developments in the arts, architecture, and jurisprudence, as well as liturgical and scriptural studies. The English monk ] was invited to Aachen, and brought with him the precise ] education that was available in the monasteries of ]. The return of this Latin proficiency to the kingdom of the Franks is regarded as an important step in the development of ]. Charlemagne's ] made use of a type of script currently known as ], providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. After the decline of the Carolingian dynasty, the rise of the ] in Germany was accompanied by the ]. | |||

| Charlemagne's court in ] was the centre of a cultural revival that is sometimes referred to as the "]". This period witnessed an increase of literacy, developments in the arts, architecture, and jurisprudence, as well as liturgical and scriptural studies. The English monk ] was invited to Aachen, and brought with him the precise ] education that was available in the monasteries of ]. Charlemagne's ] made use of a new type of script known as ], providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. Charlemagne also sponsored changes in the church liturgy, imposing the Roman form of church service on his domains as well as the ] in the churches. An important activity for scholars during the Carolingian period was the copying, correcting, and dissemination of basic works on both religious and secular topics, in order to further learning. New works on religious topics as well as new textbooks were also produced.<ref name=Colish66>Colish ''Medieval Foundations'' pp. 66–70</ref> | |||

| ''See also the careers of ], ], and ].'' | |||

| ===Breakup of the Carolingian empire=== | ===Breakup of the Carolingian empire=== | ||

| {{ |

{{main|Holy Roman Empire|Viking Age}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| While Charlemagne planned to continue the Frankish tradition of dividing his kingdom between all his heirs, this came to nothing as only one son, ], was still alive in 813. That year, Charlemagne crowned Louis as his successor as king and co-emperor, and died in 814. Louis's long reign of 26 years was marked by numerous divisions of the empire among his sons and, after 829, numerous civil wars between various alliances of father and sons against other sons to determine how the empire would be divided. Eventually, the final result was that Louis recognized his eldest son ] as emperor and gave him Italy. Louis divided the rest of the empire between Lothair and ], his youngest son. Lothair received ], which comprised the empire on both banks of the Rhine and eastwards, leaving Charles ], which comprised the empire to the west of the Rhineland and the Alps. ], the middle child, who had been rebellious to the last, was allowed to keep Bavaria under the suzerainty of his elder brother. The division was not undisputed. ], the emperor's grandson, rebelled in a contest for Aquitaine, while Louis the German tried to annex all of East Francia. Louis died in 840, with the empire still in chaos.<ref name=Bauer427>Bauer ''History of the Medieval World'' pp. 427–431</ref> | |||

| While Charlemagne continued the Frankish tradition of dividing the ''regnum'' (kingdom) between all his heirs (at least those of age), the assumption of the ''imperium'' (imperial title) supplied a unifying force not available previously. Charlemagne was succeeded by his only legitimate son of adult age at his death, ]. | |||

| A three-year civil war followed his death. By the ] (843), a kingdom between the ] and ] rivers was created for Lothair to go with his lands in Italy, and his imperial title was recognized. Louis the German was in control of Bavaria and the eastern lands in modern-day Germany. Charles the Bald got the western Frankish lands, comprising most of modern-day France.<ref name=Bauer427/> Charlemagne's grandsons and great-grandsons divided their kingdoms between their descendants, eventually causing all internal cohesion to be lost.<ref name=Backman139>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' p. 139</ref> | |||

| Louis's long reign of 26 years was marked by numerous divisions of the empire among his sons and, after 829, numerous civil wars between various alliances of father and sons against other sons to determine a just division by battle. The final division was made at ] in 838. The Emperor Louis recognized his eldest son ] as emperor and confirmed him in the ] (Italy). He divided the rest of the empire between Lothair and ], his youngest son, giving Lothair the opportunity to choose his half. He chose ], which comprised the empire on both banks of the Rhine and eastwards, leaving Charles ], which comprised the empire to the west of the Rhineland and the Alps. ], the middle child, who had been rebellious to the last, was allowed to keep his subregnum of Bavaria under the suzerainty of his elder brother. The division was not undisputed. ], the emperor's grandson, rebelled in a contest for Aquitaine, while Louis the German tried to annex all of East Francia. In two final campaigns, the emperor defeated both his rebellious descendants and vindicated the division of Crémieux before dying in 840. | |||

| The breakup of the Carolingian Empire was accompanied by the invasions, migrations, and raids of external foes. The Atlantic and northern shores were harassed by the ], who also raided the British Isles and settled in both Britain and Ireland as well as the distant island of Iceland. A further settlement of Vikings was made in France in 911 under the chieftan ], who received permission from the Frankish king ] to settle in what became ].<ref name=Backman141>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 141–144</ref> The eastern parts of the Frankish kingdoms, especially Germany and Italy, were under constant Magyar assault until their great defeat at the ] in 955.<ref name=Backman144>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 144–145</ref> The breakup of the ] in the Muslim world meant that the Islamic world was fragmented into a number of smaller political states, some of whom began expanding into Italy and Sicily, as well as over the Pyrenees into the southern parts of the Frankish kingdoms.<ref name=Bauer147>Bauer ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 147–149</ref> | |||

| ] in the 10th century. Most European nations were praying for mercy: "Sagittis hungarorum libera nos Domine" - "Lord save us from the arrows of Hungarians"]] | |||

| A three-year civil war followed his death. At the end of the conflict, Louis the German was in control of East Francia and Lothair was confined to Italy. By the ] (843), a kingdom of ] was created for Lothair in ] and Burgundy, and his imperial title was recognized. East Francia would eventually morph into the ] and West Francia into the ], around both of which the history of Western Europe can largely be described as a contest for control of the middle kingdom. Charlemagne's grandsons and great-grandsons divided their kingdoms between their sons until all the various ''regna'' and the imperial title fell into the hands of ] by 884. He was deposed in 887 and died in 888, to be replaced in all his kingdoms but two (Lotharingia and East Francia) by non-Carolingian "petty kings". The Carolingian Empire was destroyed, though the imperial tradition would eventually lead to the Holy Roman Empire in 962. | |||

| Efforts by local kings to fight back the invaders led to the formation of new political entities. In Britain, King ] in the late 9th century came to a settlement with the Viking invaders, with Danish settlements in Northumbria, Mercia, and parts of East Anglia.<ref name=Collins378>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe''pp. 378–385</ref> By the middle of the 10th century, Alfred's successors had conquered Northumbria, and restored English control over most of the southern part of the island of Britain.<ref name=Collins387>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' p. 387</ref> In the early 10th century, the ] dynasty had established itself in Germany, and the Ottonians were engaged in driving back the Magyar invaders. Their efforts culminated in the coronation in 962 of ] as emperor.<ref name=Collins394>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 394–404</ref> Italy was drawn into the Ottonian sphere by the late 10th century, after a period of instability.<ref name=Wickham435>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 435–439</ref> The western Frankish kingdom was more fragmented and although a nominal king remained theoretically in charge, much of the political power had devolved down to the local lords.<ref name=Wickham439>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 439–444</ref> | |||

| The breakup of the Carolingian Empire was accompanied by the invasions, migrations, and raids of external foes as not seen since the ]. The Atlantic and northern shores were harassed by the ], who forced Charles the Bald to issue the ] against them and who ]. The eastern frontiers, especially Germany and Italy, were under constant ] assault until their great defeat at the ] in 955.<ref>.</ref> The ] also managed to establish bases at ] and ], to ] and to conquer the islands of ], ], and ], and their ] raided the Mediterranean coasts, as did the Vikings. The Christianization of the pagan Vikings provided an end to that threat. | |||

| Missionary efforts to Scandinavia during the 9th and 10th centuries helped strengthen the growth of kingdoms there. Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian kingdoms gained power and territory in the course of the 9th and 10th centuries, and some of the kings converted to Christianity, although the process was not complete by 1000. Scandinavians also expanded and colonized throughout Europe. Besides the settlements in Ireland, England, and Normandy, further settlement took place in what became Russia as well as in Iceland. Swedish traders and raiders ranged down the rivers of the Russian steppe, and even attempted to seize Constantinople in 860 and in 907.<ref name=Collins385>Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 385–389</ref> Christian Spain, initially driven into a small section of the peninsula in the north, expanded slowly south during the 9th and 10th centuries, establishing the kingdoms of ] and ] in the process.<ref name=Wickham500>Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 500–505</ref> | |||

| ===Art and architecture=== | ===Art and architecture=== | ||

| {{main|Medieval art|Medieval architecture}} | {{main|Medieval art|Medieval architecture}} | ||

| {{see|Migration Period art|Pre-Romanesque art and architecture}} | |||

| ] Ravenna, Italy 548 AD]] | |||

| ].England 662 AD]] | |||

| Few truly large stone buildings were attempted between the Constantinian basilicas of the 4th century and the 8th century, but many smaller stone buildings were built. At this time, the establishment of churches and monasteries, and a comparative political stability, caused the development of a form of stone architecture loosely based upon Roman forms and hence later named ]. Where available, Roman brick and stone buildings were recycled for their materials. From the fairly tentative beginnings known as the ], the style flourished and spread across Europe in a remarkably homogeneous form. The features are massive stone walls, openings topped by semi-circular arches, small windows, and, particularly in France, arched stone vaults and arrows. | |||

| ] is one of the most famous artworks of the Early Middle Ages.]] | |||

| In the decorative arts, Celtic and Germanic barbarian forms were absorbed into ], although the central impulse remained Roman and Byzantine. High quality jewellery and religious imagery were produced throughout Western Europe; ] and other monarchs provided patronage for religious artworks such as ] and books. Some of the principal artworks of the age were the fabulous ] produced by monks on ], using gold, silver, and precious pigments to illustrate biblical narratives. Early examples include the ] and many Carolingian and Ottonian Frankish manuscripts. | |||

| Few truly large stone buildings were attempted between the Constantinian basilicas of the 4th century and the 8th century, but many smaller stone buildings were built during the 6th and 7th centuries. By the beginning of the 8th century, the Carolingian empire revived the basilica form of architecture.<ref name=Stalley29>Stalley ''Early Medieval Architecture'' pp. 29–35</ref> One feature of the renewed basilica was the use of a ],<ref name=Stalley43>Stalley ''Early Medieval Architecture'' pp. 43–44</ref> or the "arms" of a cross-shaped building that are perpendicular to the long ].<ref name=Cosman247>Cosman ''Medieval Wordbook'' p. 247</ref> Other new features of religious architecture include the crossing tower<ref name=Stalley45>Stalley ''Early Medieval Architecture'' p. 45</ref> and a monumental entrance to the church, usually at the west end of the building.<ref name=Stalley49>Stalley ''Early Medieval Architecture'' p. 49</ref> | |||

| In the decorative arts, Celtic and Germanic barbarian forms were absorbed into ], although the central impulse remained Roman and Byzantine. High quality jewellery and religious imagery were produced throughout Western Europe; Charlemagne and other monarchs provided patronage for religious artworks such as ] and books. Some of the principal artworks of the age were the fabulous ] produced by monks on ], using gold, silver, and precious pigments to illustrate biblical narratives. Early examples include the ] and many Carolingian and Ottonian Frankish manuscripts.<ref name=Adams171>Adams ''History of Western Art'' pp. 171–175</ref> | |||

| ==High Middle Ages== | ==High Middle Ages== | ||

| {{main|High Middle Ages|Feudalism}} | {{main|High Middle Ages|Feudalism}} | ||

| ] dating from the early 14th century, showing the end of Psalm 145 and the start of Psalm 146.]] | ] dating from the early 14th century, showing the end of Psalm 145 and the start of Psalm 146.]] | ||

| ], France]] | |||

| ] during the ], 1099]] | |||

| ] was brought to Florence in 1396 to teach Greek]] | |||

| ===Society and economic life=== | |||

| The High Middle Ages were characterized by the urbanization of Europe, military expansion, and intellectual revival that historians identify between the 11th century and the end of the 13th century. This revival was aided by the conversion of the raiding ] and ] to Christianity, by the assertion of power by ] to fill the power vacuum left by the Carolingian decline, and not least by the increased contact with Islamic civilization, which had preserved and elaborated all the classic Greek literature forgotten in Europe after the collapse of The Roman Empire. This was now retranslated into Latin, along with newer works of important advances in science and technology (see ]). | |||

| The High Middle Ages saw an ]. Rough estimates of the population increase from the year 1000 until 1347 indicate that the population of Europe increased from 35 million to 80 million. The exact cause or causes of this growth remains unclear, although improved agricultural techniques, the decline of slaveholding, a more clement climate, and the lack of invading outsiders have all been put forwards as reasons for the population increase.<ref name=Jordan5>Jordan ''Europe in the High Middle Ages'' pp. 5–12</ref><ref name=Backman156>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' p. 156</ref> As much as 90 percent of the European population remained rural peasants. Many of them, however, were no longer settled in isolated farms but had gathered into small communities, usually known as manors or villages.<ref name=Backman156/> These peasants were often subject to noble overlords and owed them rents and other services, in a system known as ]. There remained, however, a few free peasants throughout this period and beyond.<ref name=Backman164>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 164–165</ref> | |||

| The High Middle Ages saw an ]. This population flowed into towns, sought conquests abroad, or cleared land for cultivation. The cities of antiquity had been clustered around the Mediterranean. By 1200, the growing urban centres were in the centre of the continent, connected by roads or rivers. By the end of this period, Paris might have had as many as 200,000 inhabitants.<ref name="Rosenwein">{{cite book|title=A Short History of the Middle Ages|author=Rosenwein, Barbara H|publisher=Broadview Press|year=2001|isbn=1551112906}}</ref> In central and ] and in ], the rise of towns that were, to some degree, self-governing, stimulated the economy and created an environment for new types of religious and trade associations. Trading cities on the shores of the Baltic entered into agreements known as the ], and ] such as ], ], and ] expanded their trade throughout the Mediterranean. This period marks a formative one in the history of the Western state as we know it, for kings in France, England, and Spain consolidated their power during this period, setting up lasting institutions to help them govern. Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their sedentarization and conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers. Hungary, especially, became the "Gate to Europe" from Asia, and ] of Christianity against the invaders from the ] until the 16th century and the onslaught by the ].<ref>{{cite web|author=|url=http://magyarmuzeum.org/index.php?projectid=4&menuid=165 |title=History of Hungary |publisher=Magyarmuzeum.org |accessdate=2010-11-14}}</ref> The ], which had long since created an ideology of independence from the ] kings, first asserted its claims to temporal authority over the entire Christian world. The entity that historians call the ] reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of ]. ] and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously ] regions in the ] and ] northeast brought the ] of numerous native peoples to the European identity. With the brief exception of the ] and ], major barbarian incursions ceased.<ref>.</ref> | |||

| Other sections of society were the nobility, the clergy, and townsmen. Nobles, which included both ] and the simple ]s, were the exploiters of the manors and the peasants, although they did not own the lands outright, rather being granted the right to the income from a manor or other lands by an overlord in the system known as ]. During the 11th and 12th centuries, these lands, or ], came to be considered hereditary and in most areas they were no longer divisible between all the heirs as had been the case in the early medieval period. Now, instead, most fiefs and lands went to the eldest son.<ref name=Barber37>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 37–41</ref> The clergy was divided into two types - the ] who lived in the world, and the ], or those who lived under a religious rule and were usually monks.<ref name=Hamilton33>Hamilton ''Religion on the Medieval West'' p. 33</ref> Most of the regular clergy were drawn from the ranks of the nobility, the same social class that served as the recruiting ground for the upper levels of the secular clergy. The local ] priests were often drawn from the peasant class.<ref name=Barber33>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 33–34</ref> Townsmen were in a somewhat unusual position, as they did not fit into the traditional three-fold division of society into nobles, clergy, and peasants. But, during the 12th and 13th centuries, the ranks of the townsmen expanded greatly as existing towns expanded and new towns were founded.<ref name=Barber48>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 48–49</ref> | |||

| ===Crusades=== | |||

| {{main|Crusades|Reconquista}} | |||

| In central and ] and in ], the rise of towns that were, to some degree, self-governing, stimulated the economy and created an environment for new types trade associations. Trading cities on the shores of the Baltic entered into agreements known as the ], and ] such as ], ], and ] expanded their trade throughout the Mediterranean.<ref name=Barber60>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 60–67</ref> Besides new trading opportunities, the agricultural and technological improvements enabled the increase in crop yields, which in turn allowed the trade networks to expand.<ref name=Backman160>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' p. 160</ref> Rising trade required new methods of dealing with money, and gold coinage was once more minted in Europe during the High Middle Ages, at first in Italy and later in France and other countries. New forms of commercial contracts emerged, allowing risk to be shared amongst merchants. Accounting, including ], advanced and ] were invented to allow the easy transmission of money through the trading networks.<ref name=Barber74>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 74–76</ref> | |||

| The Crusades were holy wars or armed pilgrimages intended to liberate ] from Muslim control. Jerusalem was part of the Muslim possessions won during a rapid military expansion in the 7th century through the Near East, Northern Africa, and Anatolia (in modern Turkey). The first Crusade was preached by Pope ] at the ] in 1095 in response to a request from the ] emperor ] for aid against further advancement. Urban promised ] to any Christian who took the Crusader vow and set off for Jerusalem. The resulting fervour that swept through Europe mobilized tens of thousands of people from all levels of society, and resulted in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, as well as other regions. The movement found its primary support in the Franks; it is by no coincidence that the Arabs referred to Crusaders generically as "''Franj''".<ref>{{cite book|title=Crusades Through Arab Eyes |author=Maalouf, Amin |publisher=Schocken|year=1989|isbn=0805208984}}</ref> Although they were minorities within this region, the Crusaders tried to consolidate their conquests as a number of ] – the ], as well as the ], the ], and the ] (collectively ]). During the 12th century and 13th century, there were a series of conflicts between these states and surrounding Islamic ones. Crusades were essentially resupply missions for these embattled kingdoms. Military orders such as the ] and the ] were formed to play an integral role in this support. | |||

| ===Political states=== | |||

| By the end of the Middle Ages, the Christian Crusaders had captured all the Islamic territories in modern Spain, Portugal, and Southern Italy. Meanwhile, Islamic counter-attacks had retaken all the Crusader possessions on the Asian mainland, leaving a de facto boundary between Islam and ] that continued until modern times. | |||

| The High Middle Ages marks a formative one in the history of the Western state as we know it, for kings in France, England, and Spain consolidated their power during this period, setting up lasting institutions to help them govern.<ref name=Backman283>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 283–284</ref> Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers.<ref name=Barber365>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 365–380</ref> The ], which had long since created an ideology of independence from the ] kings, first asserted its claims to temporal authority over the entire Christian world. The entity that historians call the ] reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of ].<ref name=Backman262>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 262–279</ref> ] and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously ] regions in the Baltic region and ] northeast brought the ] of numerous native peoples to the European identity.<ref name=Barber371>Barber ''Two Cities'' pp. 371–372</ref> | |||

| Substantial areas of northern Europe also remained outside Christian influence until the 11th century or later; these areas also became ] during the expansionist High Middle Ages. Throughout this period, the ] was in decline, having peaked in influence during the High Middle Ages. Beginning with the ] in 1071, the empire underwent a cycle of decline and renewal, including the sacking of Constantinople by the ] in 1204. After that, ] assembled the biggest army in the history of the ], and moved his troops as a leading figure in the ], reaching ] and later ], coming back home in 1218.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://atheism.about.com/library/FAQs/christian/blchron_xian_crusades09.htm |title=Andrew II of Hungary and the fifth Crusade |publisher=Atheism.about.com |date= |accessdate=2010-11-14}}</ref> | |||

| During the early part of the High Middle Ages, Germany was under the rule of the ], who struggled to control the powerful dukes who ruled over territorial duchies that traced back to the Migration period. In 1024, the ruling dynasty changed to the ], who famously clashed with the papacy under Emperor ] over church appointments.<ref name=Backman181>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 181–186</ref> His successors continued to struggle against the papacy as well as the German nobility. After the death of Emperor ] without heirs, a period of instability arose until ] took the imperial throne in the late 12th century.<ref name=Jordan143>Jordan ''Europe in the High Middle Ages'' pp. 143–147</ref> Although Barbarossa managed to rule effectively, the basic problems remained, and his successors continued to struggle with them into the 13th century.<ref name=Jordan250>Jordan ''Europe in the High Middle Ages'' pp. 250–252</ref> | |||

| Despite another short upswing following the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the empire continued to deteriorate. | |||

| ] shown on the ]|thumb|right]] | |||

| ===Science and technology=== | |||

| {{main|Medieval science|Medieval technology}} | |||

| France, under the ], began to slowly expand it's power over the nobility, managing to expand out of the ] and to exert control over more of France as the 11th and 12th centuries.<ref name=Backman187>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 187–189</ref> They faced a powerful rival, however, in the ], who in 1066 under ], conquered England and created a cross-channel empire that would last, in various forms, throughout the rest of the Middle Ages.<ref name=Jordan59>Jordan ''Europe in the High Middle Ages'' pp. 59–61</ref><ref name=Backman189>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 189–196</ref> Under the Angevin dynasty of King ] and his sons, the kings of England ruled over not just England, but large sections of France as well,<ref name=Backman263>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' p. 263</ref> but King ] lost Normandy and the rest of the northern French possessions. Dissension amongst the English nobility over this loss and John's financial exactions to pay for his unsuccessful attempts to regain Normandy led to the nobility forcing John to concede '']'', a charter that confirmed the rights and privileges of free men in England. Under John's son, further concessions were made to the nobility, and royal power was diminished.<ref name=Backman286>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 286–289</ref> The French monarchy, however, continued to make gains against the nobility during the late 12th and 13th centuries, bringing more territories within the kingdom under their personal rule and centralizing the royal administration.<ref name=Backman289>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 289–293</ref> | |||

| ], the ], and many other universities were founded at this time.]] | |||

| ===Crusades=== | |||

| The early Middle Ages coincided with the ]. At that time, ], ], and ] were more advanced than in Western Europe. Islamic scholars both preserved and built upon earlier ] and ] traditions and added their own inventions and innovations in Islamic ] (modern Spain and Portugal). Some of this knowledge was collected after the Christian reconquest of Muslim Spain (see ]), and European scholars used it to build upon their existing knowledge and to fill in the gaps. Furthermore, much classical knowledge was not actually lost in Western Europe, but was instead scattered in monasteries all over Europe, and in the high Middle Ages it was collected and became a base for further enlightenment. | |||

| {{main|Crusades|Reconquista}} | |||

| ] during the ], 1099]] | |||

| The Crusades were wars intended to liberate ] from Muslim control. The first Crusade was preached by Pope ] at the ] in 1095 in response to a request from the ] emperor ] for aid against further advancement. Urban promised ] to anyone who took part. Tens of thousands of people from all levels of society mobilized across Europe, and captured Jerusalem in 1099 during the ]. The Crusaders consolidated their conquests as a number of ] During the 12th century and 13th century, there were a series of conflicts between these states and surrounding Islamic ones. Further crusades were called to aid these states,<ref name=MACrusades>Riley-Smith "Crusades" ''Middle Ages'' pp. 106–107</ref> or to try to regain Jerusalem, which was captured by ] in 1187.<ref name=Payne204>Payne ''Dream and the Tomb'' pp. 204–205</ref> Military religious orders such as the ] and the ] were formed and went on to play an integral role in the Crusader states.<ref name=Lock353>Lock ''Routledge Companion to the Crusades'' pp. 353–356</ref> In 1203, the ] was diverted from the Holy Land to Constantinople, and captured that city in 1204, setting up a ]<ref name=Lock156>Lock ''Routledge Companion to the Crusades'' pp. 156–161</ref> and greatly weakening the Byzantine Empire, which finally recaptured Constantinople in 1261, but the Byzantines never regained their former strength.<ref name=Backman299>Backman ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'' pp. 299–300</ref> By 1291, the Crusader states had all been either captured or forced off the mainland, with a titular kingdom of Jerusalem surviving on the island of Cyprus for a number of years after 1291.<ref name=Lock122>Lock ''Routledge Companion to the Crusades'' p. 122</ref> | |||

| At the same time, ] were invited to Italy to teach Greek, and brought with them much classical knowledge. This migration of ] scholars and other emigrates from ] and ] during the decline of the ] (1203–1453) were to make a big contribution in the High Middle Ages in Western Europe. | |||

| ] was built during the Crusades]] | |||

| These emigrates were grammarians, humanists, poets, writers, printers, lecturers, musicians, astronomers, architects, academics, artists, scribes, philosophers, scientists, politicians and theologians.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://how-to-learn-any-language.com/e/polyglots/greeks-in-italy.html |title=Greeks in Italy |publisher=How-to-learn-any-language.com |date=2007-06-19 |accessdate=2011-12-08}}</ref> They brought to Western Europe the far greater preserved and accumulated knowledge of their own (Greek) civilization. | |||

| ] (c. 1214–1294) is sometimes credited as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method inspired by the works of ].]] | |||

| One of these Greeks was ] (1355–1415), a pioneer in the introduction of Greek literature to ] during the ]. In 1396, ], the chancellor of the University of Florence, invited Chrysolora to come and teach Greek ] and literature. Chrysoloras also translated the works of ] and ]'s '']'' into Latin. | |||

| Popes called for crusaders to take place other than the Holy Land, with crusades being proclaimed in Spain, southern France, and along the Baltic.<ref name=MACrusades/> The Spanish crusades became fused with the ], or reconquest, of Spain from the Moslems. Although the Templars and Hospitallers took part in the Spanish crusades, Spanish military religious orders were also founded in imitation of the Templars and Hospitallers, with most of them becoming part of the two main orders of ] and ] by the beginning of the 12th century.<ref name=Lock205>Lock ''Routledge Companion to the Crusades'' pp. 205–213</ref> Northern Europe also remained outside Christian influence until the 11th century or later; these areas also became crusading venues as part of the ] of the 12th through the 14th centuries. This too spawned a military order, the ]. Another order, the ], although originally founded in the Crusader states, focused much of its activity in the Baltic after 1225, and in 1309 it moved its headquarters to Marienburg in Prussia.<ref name=Lock213>Lock ''Routledge Companion to the Crusades'' pp. 213–224</ref> | |||

| Also during the ] of ] 1204–1261, classical knowledge was brought back to the West by the ]. | |||

| ===Intellectual life=== | |||