| Revision as of 15:09, 12 April 2010 editLecen (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users18,620 edits →Juan Manuel de Rosas dictatorship: Fine. Adding Argentine sources.← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:12, 12 April 2010 edit undoCambalachero (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers53,993 edits →Juan Manuel de Rosas dictatorship: This is an example of the reasons why does this article needs to check other sourcesNext edit → | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| ] ] was elected governor of ] after the brief period of anarchy following the end of the ] in 1828. In theory, Rosas only held as much power as governors of the other Argentine provinces. But in reality, he ruled over the entire ], as the country was then known. Although allied with the ], a faction which demanded greater provincial autonomy, in practice Rosas exercised control over the other provinces through a combination of negotiation, bribery and military pressure.<ref name=v447>Vainfas, p.447</ref> He was able to draw on the wealth of Buenos Aires, generated in part because all of Argentina's international trade had to pass through its port. With the exception of a short period between 1832 and 1835, he governed the country for more than 20 years as dictator<ref name=v447/> until defeated in 1852 at ].<ref name="h113"/> Rosas' government became more corrupt and despotic as time went on, and some 14,000 of the political opposition (the ]) fled to Uruguay to escape his repression.<ref>Vianna, p.528</ref> | ] ] was elected governor of ] after the brief period of anarchy following the end of the ] in 1828. In theory, Rosas only held as much power as governors of the other Argentine provinces. But in reality, he ruled over the entire ], as the country was then known. Although allied with the ], a faction which demanded greater provincial autonomy, in practice Rosas exercised control over the other provinces through a combination of negotiation, bribery and military pressure.<ref name=v447>Vainfas, p.447</ref> He was able to draw on the wealth of Buenos Aires, generated in part because all of Argentina's international trade had to pass through its port. With the exception of a short period between 1832 and 1835, he governed the country for more than 20 years as dictator<ref name=v447/> until defeated in 1852 at ].<ref name="h113"/> Rosas' government became more corrupt and despotic as time went on, and some 14,000 of the political opposition (the ]) fled to Uruguay to escape his repression.<ref>Vianna, p.528</ref> | ||

| The Argentine ruler established an eccentric dictatorship. All men were obliged to have a mustashe, even if painted or simply a fake one.<ref> "... llevaban algunos bigotes naturales Y otros los lucían postizos, obedeciendo á las indicaciones oficiales" ''in'' Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.95</ref> Heads of murdered political dissidents were put in public display in streets.<ref> "Las cabezas asi desprendidas del cuerpo Y conservando aùn sus crispaciones, no causaban horror a los ejectuantes. Habiase establecido una especie de tolerancia senstitiva que les permitia manejarlas como qualquer objeto de uso comum. Se jugaba con ellas a las bochas. Esto es notorio. Y de largas distancias enviaban las de los anivajes unitarios, como estimables regalos para el gusto del Restaurador. Por este procedimento le fué remitida por el comandante accidental del lejano Fuerte Argentino la del salvaje unitario Domingo Rodriguez, bien acondicionada en vinagre Y asseriu para que los ultimo estertores de la muerte llegaran hasta el tan frescos como fuere posible. Dentro de un pequeño cajon, segun reza la nota del coronel Y comandante en jefe de la División del Azul don Juan Aguilera vino a sus manos...". "La del coronel don Pedro Castelli es de igual modo remitida por don Prudencio Rosas al seño juez de paz Y comandante militar de Dolores don Mariano Ramirez acompañada de una nota historica en la cual: "con la mas grata satisfacción" envia el famoso regalo afin de ser colocada em medio de la plaza...." ''in'' Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, pp.99-117</ref> Every Argentine citizen, men and women, had to wear red clothes (the federalist symbol) and anyone spotted with green or blue (unitarians's symbols) was to be executed.<ref>Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.69</ref> No one was allowed to walk in the streets after 10 p.m.<ref>Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.I, p.250</ref> Rosas's daughter, Manuelita Rosas, kept for herself the ears of her father's enemies mixed with salt in a silver salver.<ref>Capdevila, Arturo. ''Las Visesperas de Caseros''. Buenos Aires: Cabault & Cia, 1928, pp.50-51</ref> |

The Argentine ruler established an eccentric dictatorship. All men were obliged to have a mustashe, even if painted or simply a fake one.<ref> "... llevaban algunos bigotes naturales Y otros los lucían postizos, obedeciendo á las indicaciones oficiales" ''in'' Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.95</ref> Heads of murdered political dissidents were put in public display in streets.<ref> "Las cabezas asi desprendidas del cuerpo Y conservando aùn sus crispaciones, no causaban horror a los ejectuantes. Habiase establecido una especie de tolerancia senstitiva que les permitia manejarlas como qualquer objeto de uso comum. Se jugaba con ellas a las bochas. Esto es notorio. Y de largas distancias enviaban las de los anivajes unitarios, como estimables regalos para el gusto del Restaurador. Por este procedimento le fué remitida por el comandante accidental del lejano Fuerte Argentino la del salvaje unitario Domingo Rodriguez, bien acondicionada en vinagre Y asseriu para que los ultimo estertores de la muerte llegaran hasta el tan frescos como fuere posible. Dentro de un pequeño cajon, segun reza la nota del coronel Y comandante en jefe de la División del Azul don Juan Aguilera vino a sus manos...". "La del coronel don Pedro Castelli es de igual modo remitida por don Prudencio Rosas al seño juez de paz Y comandante militar de Dolores don Mariano Ramirez acompañada de una nota historica en la cual: "con la mas grata satisfacción" envia el famoso regalo afin de ser colocada em medio de la plaza...." ''in'' Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, pp.99-117</ref> Every Argentine citizen, men and women, had to wear red clothes (the federalist symbol) and anyone spotted with green or blue (unitarians's symbols) was to be executed.<ref>Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.69</ref> No one was allowed to walk in the streets after 10 p.m.<ref>Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.I, p.250</ref> Rosas's daughter, Manuelita Rosas, kept for herself the ears of her father's enemies mixed with salt in a silver salver.<ref>Capdevila, Arturo. ''Las Visesperas de Caseros''. Buenos Aires: Cabault & Cia, 1928, pp.50-51</ref> | ||

| Detractors of Rosas accused him of having afroamerican slaves,<ref>This scene was seen by ] who told to ] and is also confirmed by ] ''in'' Meija, Ramos. ''Rosas y su Tiempo''. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, pp.289-299</ref> and later historians like ] took such a thing as fact. However, effords to try to confirm this failed.<ref name="Esclavos">{{cite book | |||

| |title= Juan Manuel de Rosas, el maldito de la historia oficial | |||

| |last= O'Donnell | |||

| |first= Pacho | |||

| |authorlink= Pacho O'Donnell | |||

| |year= 2009 | |||

| |publisher= Grupo Editorial Norma | |||

| |location= Buenos Aires | |||

| |isbn= 978-987-545-555-9 | |||

| |pages= 126-127}}</ref> On the contrary, afroamericans were allowed to take public jobs during Rosas government, to gather themselves in societies relating to their african ancestory,<ref>"''Los negros encontraron en el caudillo de la pampa una decidida protección: les hizo conseciones y proporcionó fondos para que se estableciesen asociaciones con la denominación de las respectivas tribus africanas a que debían su origen.'' Memories of ]</ref> and were granted freedom if joining the armies. Even so, most of the afroamerican soldiers in the armies were actually slaves that had escaped from Brazil, a country with a high level of slavery, who were recognized as free men when entering the Confederation and received military protection from their old masters when becoming soldiers. This was one of the reasons of the political stir between Argentina and Brazil.<ref name="Esclavos"/> | |||

| Rosas desired to recreate the former ], an old Argentine dream, placing Argentina at the center of a powerful, republican state.<ref name="Estado-maior do Exército, p.546">Estado-maior do Exército, p.546</ref><ref>Doratioto (2002), p.25</ref><ref name="Maia, p.255">Maia, p.255</ref><ref name="Lima, p.158">Lima, p.158</ref><ref>Pedrosa, p.50</ref> To achieve this, it would be necessary to annex the three neighbouring nations of ], ] and ], as well as a ] of ].<ref name=l160>Lyra (v.1), p.160</ref> Rosas first had to gather allies across the region who shared his vision. In some instances, this entailed becoming involved in the internal politics of neighboring countries to back those sympathetic to union with Argentina, and occasionally even financing rebellions and wars.<ref name=l160/> | Rosas desired to recreate the former ], an old Argentine dream, placing Argentina at the center of a powerful, republican state.<ref name="Estado-maior do Exército, p.546">Estado-maior do Exército, p.546</ref><ref>Doratioto (2002), p.25</ref><ref name="Maia, p.255">Maia, p.255</ref><ref name="Lima, p.158">Lima, p.158</ref><ref>Pedrosa, p.50</ref> To achieve this, it would be necessary to annex the three neighbouring nations of ], ] and ], as well as a ] of ].<ref name=l160>Lyra (v.1), p.160</ref> Rosas first had to gather allies across the region who shared his vision. In some instances, this entailed becoming involved in the internal politics of neighboring countries to back those sympathetic to union with Argentina, and occasionally even financing rebellions and wars.<ref name=l160/> | ||

Revision as of 19:12, 12 April 2010

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

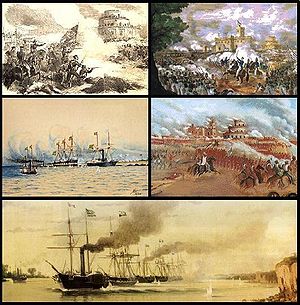

| Platine War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Brazilian 1st Division in the Caseros; Uruguayan infantry aiding Entre Rios cavalry in Caseros; Beginning of the Passage of the Tonelero; Charge of Urquiza's cavalry in Caseros; Passage of the Tonelero. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

20,000 Brazilians 15,000+ Argentines and Uruguayans | 34,500+ Argentines and Uruguayans | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400+ dead | 1,200+ dead | ||||||

The Platine War, also known as the War against Oribe and Rosas (August 18, 1851 – February 3, 1852) was fought between the Argentine Confederation and an alliance of the Empire of Brazil, Uruguay and the Argentine provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes. The war was part of a long-running contest between Argentina and Brazil for influence over Uruguay and Paraguay and hegemony over the regions bordering the Río de la Plata. The conflict took place in Uruguay, on the Río de la Plata and in the northeast of Argentina.

The civil war in Uruguay following its independence from Brazil combined with Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas's ambitions to generated instability in the Platine region. Argentina considered Uruguay and Paraguay to lie within its sphere of influence, and there was a desire to see its borders incorporate the area occupied by the old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. These objectives ran contrary to Brazilian interests and sovereignty, since the old viceroyalty encompassed lands which had since been assimilated into Brazil's province of Rio Grande do Sul. Conflict between Brazilian and Argentine interests and influence in the region had already led to the Argentina-Brazil War, and would spark two future wars.

The Brazilian government, along with Uruguay and the Argentine rebel provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes, formed an offensive alliance against the Argentine Confederation. Rosas declared war on Brazil, followed by the advance of allied forces into Uruguayan territory. The allied army was then split, with the main arm advancing through Argentine territory to engage Rosas's defenses and the other launching a seaborne assault directed at the Argentine capital.

The Platine War ended in 1852 with the allied victory at the Battle of Caseros. This established Brazilian hegemony over much of South America, and further ushered in a period of economic and political stability in the Empire of Brazil itself. However, the other nations in the Platine region continued to experience turmoil, with internal disputes among political factions in Uruguay and a long civil war in a divided Argentina.

Background

Juan Manuel de Rosas dictatorship

Main article: Juan Manuel de Rosas

Don Juan Manuel de Rosas was elected governor of Buenos Aires after the brief period of anarchy following the end of the Argentina-Brazil War in 1828. In theory, Rosas only held as much power as governors of the other Argentine provinces. But in reality, he ruled over the entire Argentine Confederation, as the country was then known. Although allied with the Federalists, a faction which demanded greater provincial autonomy, in practice Rosas exercised control over the other provinces through a combination of negotiation, bribery and military pressure. He was able to draw on the wealth of Buenos Aires, generated in part because all of Argentina's international trade had to pass through its port. With the exception of a short period between 1832 and 1835, he governed the country for more than 20 years as dictator until defeated in 1852 at Caseros. Rosas' government became more corrupt and despotic as time went on, and some 14,000 of the political opposition (the Unitarians) fled to Uruguay to escape his repression.

The Argentine ruler established an eccentric dictatorship. All men were obliged to have a mustashe, even if painted or simply a fake one. Heads of murdered political dissidents were put in public display in streets. Every Argentine citizen, men and women, had to wear red clothes (the federalist symbol) and anyone spotted with green or blue (unitarians's symbols) was to be executed. No one was allowed to walk in the streets after 10 p.m. Rosas's daughter, Manuelita Rosas, kept for herself the ears of her father's enemies mixed with salt in a silver salver.

Detractors of Rosas accused him of having afroamerican slaves, and later historians like John Lynch took such a thing as fact. However, effords to try to confirm this failed. On the contrary, afroamericans were allowed to take public jobs during Rosas government, to gather themselves in societies relating to their african ancestory, and were granted freedom if joining the armies. Even so, most of the afroamerican soldiers in the armies were actually slaves that had escaped from Brazil, a country with a high level of slavery, who were recognized as free men when entering the Confederation and received military protection from their old masters when becoming soldiers. This was one of the reasons of the political stir between Argentina and Brazil.

Rosas desired to recreate the former Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, an old Argentine dream, placing Argentina at the center of a powerful, republican state. To achieve this, it would be necessary to annex the three neighbouring nations of Bolivia, Uruguay and Paraguay, as well as a portion of the southern region of Brazil. Rosas first had to gather allies across the region who shared his vision. In some instances, this entailed becoming involved in the internal politics of neighboring countries to back those sympathetic to union with Argentina, and occasionally even financing rebellions and wars.

Paraguay had considered itself a sovereign nation since 1811, but it was not recognized as such by any other nation. Argentina viewed it as a rebellious province. The Paraguayan dictator José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia decided that the best way to maintain his own rule and the independence of Paraguay from Argentina was to isolate the country from contacts with the outside world. It was for this reason that, up until 1840, the country had avoided establishing diplomatic relations with other nations. With the death of Francia, this policy began to shift, and his successor Don Carlos Antonio López signed two treaties in July 1841. These were the 'Friendship, Commerce and Navigation' and 'Limits' agreements made with the Argentine province of Corrientes, which itself had broken away from Argentina under Rosas. Meanwhile, Rosas began to place pressure on Paraguay. Rosas continued to refuse recognition of Paraguayan independence and placed a blockade on international traffic to and from Paraguay on the Paraná river.

La Guerra Grande

Main article: Uruguayan Civil WarUruguay's internal troubles, including the long civil war, "La Guerra Grande", were heavily influential factors leading up to the Platine War. The old Brazilian province of Cisplatina had become the Oriental Republic of Uruguay after the Argentina-Brazil War of the 1820s. Uruguay's first constitution was adopted in 1830, and Don Fructuoso Rivera was elected its first president. The voting results, however, were disputed by Rivera's opponent, Don Juan Antonio Lavalleja. Lavalleja had gained fame during 1825 for declaring, with the support of the "Thirty-Three Orientals", Cisplatine's independence from Brazil. In due course Lavalleja attempted to resolve the disputed election by force, marking the beginning of a long civil war. Rivera and Lavalleja became associated with two rival political parties: the Blancos which supported Lavalleja, and the Colorados which were partisans of Rivera.

Buenos Aires fort, c. 1852. Today the Argentine presidential palace (Casa Rosada) occupies the site.

Buenos Aires fort, c. 1852. Today the Argentine presidential palace (Casa Rosada) occupies the site. View of the Río de la Plata (River Plate) from Buenos Aires, 1852. The Argentine capital was the center of Rosas' power.

View of the Río de la Plata (River Plate) from Buenos Aires, 1852. The Argentine capital was the center of Rosas' power.

Lavalleja soon discovered that Rosas in neighbouring Buenos Aires was interested in aiding him financially and militarily. In 1832, Lavalleja began to receive aid from Bento Gonçalves, a soldier and farmer from the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul. Gonçalves had been encouraged by Rosas to rebel against the Brazilian government, with the ultimate aim of enabling Argentina to annex the province of Rio Grande do Sul. Together, Lavalleja and Gonçalves initiated a military campaign in Uruguay which was characterised by extensive violence and theft.

Rivera completed his term of office as President in October 1834. Manuel Oribe, like Lavalleja a member of the Blanco party, was elected in March 1835 and called for an end to the anarchy of the previous years. But election of the new president caused a shift in regional alliances. Outgoing president Rivera rebelled against Oribe but was militarily defeated and retreated into Rio Grande do Sul. There he joined forces with Gonçalves and his men, until then allies of Rosas. Lavajella, however, remained loyal to Oribe. Rivera and Gonçalves then invaded Uruguay and overran most of the country outside the environs of the capital, Montevideo. Defeated, Oribe renounced his position as president and decamped to Argentina. Rivera was then reelected president in 1838.

Rosas was determined to restore Argentine suzerainty over Uruguay and take revenge on Gonçalves, and launched a sequence of interventions. In 1839 an army led by Pascual Echagüe, Lavalleja, Oribe and Justo José de Urquiza, (Governor of Entre Rios) was quickly defeated by Rivera. At this point, Lavalleja left the conflict for good and did not further participate in the civil war. Rosas sent another army of Argentines and Uruguayans in 1845, led by Oribe and Urquiza, and this time defeated Rivera's forces, slaughtering the survivors. Rivera was one of the few who managed to escape, and went into exile in Rio de Janeiro. The remains of the Colorado Uruguayan government in Montevideo chose Joaquín Suárez as the president's successor, as Oribe's forces began subjecting the capital to a siege. The violence in Uruguay escalated, with Oribe's men killing more than 17,000 Uruguayans and 15,000 Argentinians during the conflict.

The hostilities began to spread beyond Uruguay's borders. In 1847, Francisco Solano López sponsored a revolt led by Joaquín Madariaga and José María Paz against the Rosas regime in Argentina. This revolt was ultimately suppressed by de Urquiza. Meanwhile Oribe, having gained control of nearly all of Uruguay, enabled Rosas to launch an invasion of southern Brazil, his forces stealing cattle, pillaging ranches, and liquidating political enemies as they went. More than 188 Brazilian farms were attacked, with 814,000 cattle and 16,950 horses stolen. Francisco Pedro de Abreu, Baron of Jacuí independently decided to retaliate, making raids into Uruguay which became known as "Califórnias", in reference to the violence in western North America during California's revolt against Mexico, its brief independence and subsequent anexation by the U.S. As conflict further escalated with the support of Rosas for the Blancos, anarchy over wide areas in the region, and a growing threat to trade, the era's two greatest powers, France and Great Britain, were induced to declare war on Argentina. Buenos Aires suffered repeated attacks from Anglo-French fleets and endured several blockades. The Argentine government was able to mount effective resistance, however, leading to a peace accord in 1849.

The war begins

The Empire of Brazil reacts

By the middle of the 19th century, the Empire of Brazil was the richest and most powerful nation in Latin America. It thrived under democratic institutions and a constitutional monarchy, and prided itself on the absence of the caudillos, dictators and coups d'état which were common across the rest of the continent. During the minority of emperor Dom Pedro II, however, there had been internal rebellions driven by local disputes for power within a few provinces. One of these, the War of Tatters, had been led by Gonçalves, as noted above. And although it began as just another local squabble within Rio Grande do Sul, it escalated into a fully fledged separatist revolt, aided by financial support from Rosas. Because there was no foreign intervention, Brazil was confident that its security was not threatened and that it would be able to handle the situation. Most of Rio Grande do Sul, including the largest and richest cities, remained loyal to the Emperor, who chose to pardon the rebels instead of prosecuting them. This helped lead to order and stability being restored. Once defeated, even Gonçalves, who had remained a firm monarchist even while leading the uprising against the crown, swore loyalty to the Emperor during Pedro II's inspection tour of the south in 1845.

For the Brazilian Empire, expansionist plans on the part of powerful, republican Argentina represented an existential menace to the monarchy. It also signified a threat to Brazilian hegemony across its southern borders. A successful Argentine bid to incorporate Paraguay and Uruguay into a reconstituted Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, and control of the Platine river network consequently passing into entirely hostile hands, would have threatened to cut communication between the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso and Rio de Janeiro. With river transportation denied, the alternative land routes would require months of travel instead of days. Nor was Brazil keen to share a direct border with Argentina, fearing an increased vulnerability to an invasion by Rosas.

The members of the Brazilian Cabinet could not reach agreement as to how to address the danger posed by Rosas. Some ministers advocated pursuing a peaceful outcome at any cost, and others believed the only answer was a military solution. Pedro de Araújo Lima, then President of the Council of Ministers, firmly advocated a policy of peace. He feared that Brazil was unprepared for war and that a defeat would imperil the monarchy and lead to a situation similar to that of the 1820s when the loss of Cisplatine contributed to the abdication of Dom Pedro I, the emperor's father. In 1849, however, Araújo Lima concluded that his position had become untenable and resigned from office, clearing the way for the Emperor to call José da Costa Carvalho (later the Marquis of Monte Alegre) to head the cabinet. Paulino José Soares de Sousa, a member of the pro-war faction and later Viscount of Uruguay, was chosen as the new minister of Foreign Affairs. Soares made clear his intent to deal with Argentina without foreign assistance, announcing that the "Imperial Government does not desire or judge convenient an alliance with France or any other European nation related to the matters in the Platine region. It understands that they must be resolved by the nations which are closely connected with... It will not admit European influence over America." The Empire of Brazil was determined to extend its zone of influence over South America.

The new Council of Ministers settled upon a risky alternative to resolve the complicated situation in the Platine region. Instead of undertaking a period of conscription to build up the Brazilian Army, which would have been costly, the Council decided to rely on the standing army. It sent a contingent south to secure the region. Brazil held an advantage in possessing a powerful and modern navy, along with an experienced professional army hardened by years of internal and external warfare. Up until this point, no other nation in South America possessed true navies or regular armies. Rosas' and Oribe's forces were largely made up of irregular troops on loan from those caudillos who supported them. Even a decade later, Argentina could only field an army of 6,000 men. Brazil also decided to adopt Rosas' own tactics by financing his opponents to weaken him both internally and externally.

The Alliance against Rosas

The Brazilian government set about creating a regional alliance against Rosas, sending a delegation to the region led by Honório Hermeto Carneiro Leão (later the Marquis of Paraná), who held plenipotentiary authority. He was assisted by José Maria da Silva Paranhos (later the Viscount of Rio Branco). Brazil signed a treaty with Bolívia in which Bolivia agreed to strengthen its border defenses to deter any attack by Rosas, though it declined to contribute troops to a war with Argentina. Isolationist Paraguay was more difficult to win over. Brazil made the initial overtures, becoming the first country to formally recognise Paraguayan independence in 1844. This soon led to the establishment of excellent diplomatic relations. The Brazilian ambassador in Paraguay, Pimenta Bueno, became a private councilor to Carlos López. A defensive alliance was signed on 25 December 1850 between Brazil and Paraguay, in which López agreed to supply the Empire with horses for its army. But Paraguay also refused to contribute troops to fight Rosas, believing that Justo José Urquiza, Rosas' rival in the neighbouring province of Entre Rios, secretly wished to annex Paraguay.

Brazil's involvement in the Uruguayan civil war also began to deepen. Luis Alves de Lima e Silva, the Count of Caxias, assumed the presidency (governorship) of Rio Grande do Sul and command of the four Brazilian Army divisions headquartered in the province. Beginning in 1849, the imperial government directly assisted the besieged Colorado Uruguayan government in Montevideo, and on 6 September 1850 the Uruguayan representative Andres Lamas signed an agreement with Irineu Evangelista de Sousa to transfer money to the Montevideo government through his bank. The Empire of Brazil openly declared on 16 March 1851 its support of Colorado Uruguay against Oribe, something it had been covertly doing for more than two years. This did not please the Argentine government, and they began mobilizing for war.

Brazil had also been searching for support against Rosas inside Argentina, with some success. On 1 May 1851, the Argentine province of Entre Rios, governed by Urquiza, declared to Rosas that "it is the will of its people to reassume the entire exercise of its own sovereignty and power which had been delegated to the governor of Buenos Aires." It was followed by the province of Corrientes, governed by Benjamín Virasoro, which sent the same message. Brazil encouraged and financially supported both uprisings. One of the reasons for Urquiza's betrayal of Rosas was a long-running rivalry. Rosas had tried to remove him from power several times since 1845, suspecting that the caudillo was nurturing designs for his overthrow. This was the trigger for military intervention, and Brazil sent a naval force to the Platine region, basing it near the port of Montevideo. The British Rear admiral John Pascoe Grenfell, a veteran of the Brazilian War of Independence and of the Argentina–Brazil War was appointed to lead the fleet, which reached Montevideo on 4 May 1851. His command included one frigate, seven corvettes, three brigs and six steamships. The Brazilian Armada had a total of 59 vessels of various types in 1851, including: 36 armed sailing ships, 10 armed steamships, 7 unarmed sailing ships and 6 sailing transports.

Uruguay, Brazil and the Argentine provinces of Entre Rios and Corrientes joined in an offensive alliance against Rosas on 29 May 1851. The text of the treaty declared that the objective was to protect Uruguayan independence, pacify its territory, and expell Oribe's forces. Urquiza would command the Argentine forces and Eugenio Garzón would lead the Colorado Uruguayans, with both receiving financial and military aid from the Empire of Brazil. This was followed on 2 August 1851 by landings of the first Brazilian detachments in Uruguay, consisting of approximately 300 soldiers of the 6th Battalion of Skirmishers sent to protect Fuerte del Cerro (Cerro Fort). In response, Rosas declared war against Brazil on 18 August 1851.

Allied invasion of Uruguay

The defeat of Oribe

Movement of the Allied forces into Uruguayan (left) and Argentine (right) territory.

Movement of the Allied forces into Uruguayan (left) and Argentine (right) territory.

The Count of Caxias led a Brazilian army of 16,200 professional soldiers across the border between Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay on September 4, 1851. His force consisted of four divisions, with 6,500 infantrymen, 8,900 cavalrymen, 800 artillerymen and 26 cannons, a little under half the total Brazilian army (37,000 men); while other 4,000 of his men remained in Brazil to protect its border.

The Brazilian Army entered Uruguay in three groups: the main force, consisting of the 1st and 2nd divisions - around 12,000 men, under Caxias's personal command - left from Santana do Livramento. The second force, under the command of Colonel David Canabarro departed from Quaraim, comprising the 4th division, protecting Caxias' right flank. The third force, the 3rd Division under Brigadier General José Fernandes, left from Jaguarão, protecting Caxias' left. Canabarro's 4th Division joined Caxias's troops a little after arriving at the Uruguayan town of Frutuoso, the combined force then joining up with Fernandes just before reaching Montevideo.

Meanwhile, the troops of Urquiza and Eugenio Garzón had surrounded the army of Oribe near Montevideo. Their forces numbered roughly 15,000 men, almost double Oribe's 8,500. Realising that the Brazilians were approaching and knowing that there was no hope of victory, Oribe orderered his troops to surrender without a fight on 19 October, and retreated into seclusion on his farm in Paso del Molino. The Brazilian fleet, with their ships scattered throughout the River Plate and tributaries, prevented the defeated army of Oribe from escaping into Argentina. Urquiza suggested to Grenfell that they should simply kill the resulting prisoners of war, but Grenfell refused to harm any of them. Instead, Oribe's Argentine soldiers were incorporated into the army of Urquiza, and the Uruguayans into Garzon's.

The Brazilian army safely took the remaining Blanco Uruguayan territory, fighting off Oribe's troops, who attacked their flanks in several skirmishes. On November 21 the representatives of Brazil, Uruguay, Entre Rios and Corrientes then formed another alliance in Montevideo with the objective of "freeing the Argentine people of the oppression that suffers under the tyrant rule of the Governor Rosas”.

Allied invasion of Argentina

The allied army advance

Shortly after the surrender of Oribe, the allied forces split into two groups, the plan being for one force to manoeuver upriver to sweep down on Buenos Aires from Santa Fe, while the other would make a landing at the port of Buenos Aires itself. The first of these groups, was composed of Uruguayan and Argentine troops, along with the 1st Division of the Brazilian Army under Brigadier General Manuel Marques de Sousa (later the Count of Porto Alegre). It was initially based in the town of Colonia del Sacramento in the south of Uruguay across the Río de la Plata estuary from the city of Buenos Aires.

On 17 December 1851, a squadron of Brazilian ships, consisting of four steamships, three corvettes and one brig under the command of Grenfell, forced a passage of the Paraná River in the battle which became known as the Passage of the Tonelero. The Argentines had formed a powerful defensive line at Tonelero, near the cliffs of Acevedo, protected by 16 pieces of artillery and 2,000 riflemen under the command of general Lucio Norberto Mansilla. The Argentine troops exchanged fire with the Brazilian warships but were unable to prevent from them from progressing upriver. The following day, the Brazilian ships returned and broke their way through Tonelero's defenses, carrying the remaining troops of Marques de Sousa's Brazilian division upstream towards Gualeguaichu. This second influx of ships caused Mansilla and his soldiers to withdraw in chaos, abandoning their artillery, believing that the allies were intending to land and attack their positions from the rear.

The allied army continued to make its way to the assembly point at Gualeguaichu. Urquiza and his cavalry traveled overland from Montevideo, while the infantry and artillery were carried by Brazilian warships up the Uruguay River. After meeting up, they marched west until they reached the city of Diamante on the east side of the Paraná River in the middle of December 1851. Eugenio Garzón and his the Uruguayan troops were taken from Montevideo up to Potrero Perez by Brazilian warships and continued on foot until arriving at Diamante on 30 December 1851, when all the allied forces were finally reunited. From Diamante contingents were ferried to the other side of the Paraná River, landing at Santa Fé. The Confederate Argentine troops in the region ran away without offering any resistance. The Allied Army, or the “Grand Army of South America” as it was officially called by Urquiza, marched on towards Buenos Aires.

Meanwhile, the second force, comprising the majority of the Brazilian troops (about 12,000 men) under the command of Caxias, had remained in Colonia del Sacramento. The Brazilian commander took the steamship Dom Afonso (named in honor of the late Prince Afonso) and entered the port at Buenos Aires to select the best place to disembark his troops. He expected to have to defeat the Argentine flotilla anchored there, but the force did nothing to stop him and he safely returned to Sacramento to plan his assault. The attack was prematurely aborted, however, when news arrived of the allied victory at Caseros.

Rosas defeat

The Allied army had been advancing on the Argentinian capital of Buenos Aires by land, while the Brazilian Army commanded by Caxias planned a supporting attack by sea. On 29 January at the Battle of Alvarez Field the Allied vanguard defeated a force of 4,000 Argentines led by two colonels which General Ángel Pacheco had sent to slow down the advance. Pacheco retreated. Two days later, troops under his personal command were defeated at the Battle of Marques Bridge by two allied divisions, losing 4,000 men. On 1 February 1852, the Allied troops encamped approximately nine kilometers from Buenos Aires. The next day a brief skirmish between the vanguards of both armies ended with a retreat by the Argentines.

On 3 February the Allied army encountered the main Argentine force commanded by Rosas himself. On paper, the two sides were well-matched. The Allies included 20,000 Argentines, 2,000 Uruguayans, 4,000 Brazilian elite troops(or 16,000 cavalrymen, 9,000 infantrymen and 1,000 artillerymen), totalling 26,000 men and 45 cannon. On the Argentine side, Rosas had 15,000 cavalrymen, 10,000 infantrymen and 1,000 artillerymen, totalling of 26,000 men and 60 cannon. Rosas had been able to select the best positions for his army, choosing the high ground on the slopes of a hill at Caseros which lay on the other side of a small river called the Arrojo Morón. His headquarters were based in a mansion at the top of Caseros.

The Allied commanders were de Sousa, Manuel Luis Osório (later the Marquis of Erval), Jose Maria Pirán, Jose Miguel Galán (who replaced Garzón after his unexpected death in December 1851), Urquiza, and the future Argentine presidents Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Sarmiento. These men formed a War Council, and gave orders to commence the attack. Almost immediately the forward units of the two armies began to engage in battle.

The Battle of Caseros, as the clash between the Allied and Argentine armies became known, resulted in a great victory for the opponents of Rosas. Although they started with the inferior position on the battlefield, the Allied soldiers managed to annihilate Rosas's troops in a fight that lasted for most of the day. A few minutes before the Allied forces reached Rosas' headquarters, the Argentine dictator escaped the battlefield. Disguised as a sailor, he sought out Robert Gore, British ambassador in Buenos Aires, and requested asylum. The ambassador agreed to have de Rosas and his daughter Manuelita taken to the United Kingdom, where he would spend the last twenty years of his life. The official report stated that 400 men on the Allied side had died, while the Argentine army lost 1,200. Given the duration and scale of the battle, however, this may be an underestimate.

To mark their victory, the Allied troops marched in triumph through the streets of Buenos Aires. The parades included the Brazilian Army, which insisted that their triumphal procession take place on 20 February, to mark payback for the defeat it had suffered at the hands of the Argentines in the Battle of Ituzaingó, twenty five years before on that date during the Argentina–Brazil War. The population of Buenos Aires was said to be ashamed, quiet and hostile as the Brazilians passed.

Aftermath

In Brazil

The triumph in Caseros was a pivotal military victory for Brazil. The independence of Paraguay and Uruguay was secured, and the planned Argentine invasion of Rio Grande do Sul was blocked. In a period of three years, the Empire of Brazil had destroyed any possibility of reconstituting a state encompassing the territories of old Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, a goal cherished by many in Argentina since independence. What Great Britain and France, the great powers of that time, had not achieved through interventions by their powerful navies, Brazil's army and fleet had accomplished. This represented a watershed for the history of the region, as it not only ushered in Imperial hegemony over the Platine region, but also in the rest of South America. The victory over Paraguay eighteen years later would be only a confirmation of Brazilian dominance.

Hispanic American nations from Mexico to Argentina suffered from coups d'etat, revolts, dictatorships, political upheavals, economic instability, civil wars and secessions. Brazil, on the other hand, came out of the conflict with the monarchy stronger than ever and a cessation of internal revolts. The problematic province of Rio Grande do Sul had actively participated in the war effort. As a consequence, there was increased identification with Brazil among its populace, quelling of separatist feeling, and an easier and effective integration with the rest of the nation. Internal stability also allowed Brazil to begin assuming a respected place on the international scene, coinciding with the parallel emergence of the United States which was only now establishing its borders. The European powers perceived in the Empire of Brazil a rare exception in a continent afflicted by civil wars and dictatorships. Brazil entered into a period of great economic, scientific and cultural prosperity unmatched by any of its neighbors, lasting from 1850 until the end of the monarchy.

In Argentina

Soon after Caseros, the Agreement of San Nicolas was signed. It completely modified the unitary pact of the Argentine Confederation, further decentralizing the country and giving greater autonomy to the provinces. This agreement was not accepted by the province of Buenos Aires, since it reduced its influence and power over the other provinces. It thereupon seceded from the confederation, with the result being that from 1854 to 1861, Argentina was divided into two rival, independent states which fought to reestablish dominance. On one side were the Federalists of the Argentine Confederation, led by Justo José de Urquiza. On the other were the Unitarians of Buenos Aires under Bartolomé Mitre. The civil war between them was brought to an end with the victory of the Unitarians over the Federalists at the Battle of Pavón in 1861. The result was that Buenos Aires and the provinces of the Argentine Confederation were reunited, and in 1862 the Republic of Argentina was formed with Mitre as its first president.

In Paraguay and Uruguay

With the opening of the Platine rivers, Paraguay now found it possible to contract with European technicians and Brazilian specialists to aid in its development. Unhindered access to the outside world also enabled it to import more advanced military technology. During the greater part of the 1850s, the dictator Carlos López harassed Brazilian vessels attempting to freely navigate the Paraguay River. López condoned this because he feared that the province of Mato Grosso might become a base from which an invasion from Brazil could be launched. This dispute was also leverage with the Imperial government for acceptance of his territorial demands in the region. The nation also experienced difficulties in delimiting its borders with Argentina. Argentina wanted the Gran Chaco placed completely under its flag: a demand which Paraguay could not accept, as this would entail surrendering more than half of its national territory.

The end of the Platine War did not bring a halt to conflict in the region. Peace remained out of reach in Uruguay, which remained unstable and in a state of constant crisis due to continuing internecine strife between the Blancos and Colorados. Border disputes, power struggles among diverse regional factions, and attempts to establish regional and internal influence would eventually spark the Uruguayan War as well as the later War of the Triple Alliance.

See also

- Order of Battle at the Platine War

- Brazilian intervention in Uruguay (1853)

- Uruguayan War

- War of the Triple Alliance

Bibliography

References

- Barroso, Gustavo. Guerra do Rosas: 1851-1852. Fortaleza: SECULT, 2000. Template:Pt icon

- Bueno, Eduardo. Brasil: Uma História. São Paulo: Ática, 2003. ISBN 85-08-08213-4 Template:Pt icon

- Calmon, Pedro. História de D. Pedro II. 5 v. Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio, 1975. Template:Pt icon

- Calmon, Pedro. História da Civilização Brasileira. Brasília: Senado Federal, 2002. Template:Pt icon

- Carvalho, Affonso. Caxias. Brasília: Biblioteca do Exército, 1976. Template:Pt icon

- Costa, Virgílio Pereira da Silva. Duque de Caxias. São Paulo: Editora Três, 2003. Template:Pt icon

- Dolhnikoff, Miriam. Pacto imperial: origens do federalismo no Brasil do século XIX. São Paulo: Globo, 2005. ISBN 8525040398 Template:Pt icon

- Doratioto, Francisco. Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. ISBN 8535902244 Template:Pt icon

- Doratioto, Francisco. Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional. Year 4. Issue 41. Rio de Janeiro: SABIN, 2009. Template:Pt icon

- Estado-maior do Exército. História do Exército Brasileiro: Perfil militar de um povo. v.2. Brasília: Instituto Nacional do Livro, 1972. Template:Pt icon

- Furtado, Joaci Pereira. A Guerra do Paraguai (1864-1870). São Paulo: Saraiva, 2000. ISBN 85-02-03102-3 Template:Pt icon

- Golin, Tau. A Fronteira. v.2. Porto Alegre: L&PM Editores, 2004. ISBN 8525414387 Template:Pt icon

- Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de. História Geral da Civilização Brasileira (II, v. 3). DIFEL/Difusão Editorial S.A., 1976. Template:Pt icon

- Lima, Manuel de Oliveira. O Império brasileiro. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1989. ISBN 85-319-0517-6 Template:Pt icon

- Lyra, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II (1825 – 1891): Ascenção (1825 – 1870). v.1. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1977. Template:Pt icon

- Lyra, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II (1825 – 1891): Fastígio (1870 – 1880). v.2. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 1977. Template:Pt icon

- Magalhães, João Batista. Osório : síntese de seu perfil histórico. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 1978. Template:Pt icon

- Maia, João do Prado. A Marinha de Guerra do Brasil na Colônia e no Império. 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Editora Cátedra, 1975. Template:Pt icon

- Pedrosa, J. F. Maya. A Catástrofe dos Erros. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército, 2004. ISBN 85-7011-352-8 Template:Pt icon

- Piccolo, Helga.Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional. Year 3. Issue 37. Rio de Janeiro: SABIN, 2008. ISSN: 1808-4001 Template:Pt icon

- Títara, Ladislau dos Santos. Memórias do grande exército alliado libertador do Sul da América. Rio Grande do Sul: Tipografia de B. Berlink, 1852 (Online) Template:Pt icon

- Vainfas, Ronaldo. Dicionário do Brasil Imperial. Objetiva, 2002. ISBN 85-7302-441-0 Template:Pt icon

- Vianna, Hélio. História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república, 15. ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1994. Template:Pt icon

Footnotes

- ^ Vainfas, p.447

- ^ Holanda, p.113

- Vianna, p.528

- "... llevaban algunos bigotes naturales Y otros los lucían postizos, obedeciendo á las indicaciones oficiales" in Meija, Ramos. Rosas y su Tiempo. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.95

- "Las cabezas asi desprendidas del cuerpo Y conservando aùn sus crispaciones, no causaban horror a los ejectuantes. Habiase establecido una especie de tolerancia senstitiva que les permitia manejarlas como qualquer objeto de uso comum. Se jugaba con ellas a las bochas. Esto es notorio. Y de largas distancias enviaban las de los anivajes unitarios, como estimables regalos para el gusto del Restaurador. Por este procedimento le fué remitida por el comandante accidental del lejano Fuerte Argentino la del salvaje unitario Domingo Rodriguez, bien acondicionada en vinagre Y asseriu para que los ultimo estertores de la muerte llegaran hasta el tan frescos como fuere posible. Dentro de un pequeño cajon, segun reza la nota del coronel Y comandante en jefe de la División del Azul don Juan Aguilera vino a sus manos...". "La del coronel don Pedro Castelli es de igual modo remitida por don Prudencio Rosas al seño juez de paz Y comandante militar de Dolores don Mariano Ramirez acompañada de una nota historica en la cual: "con la mas grata satisfacción" envia el famoso regalo afin de ser colocada em medio de la plaza...." in Meija, Ramos. Rosas y su Tiempo. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, pp.99-117

- Meija, Ramos. Rosas y su Tiempo. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, p.69

- Meija, Ramos. Rosas y su Tiempo. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.I, p.250

- Capdevila, Arturo. Las Visesperas de Caseros. Buenos Aires: Cabault & Cia, 1928, pp.50-51

- This scene was seen by Tomás Guido who told to Vicente Fidel López and is also confirmed by Bernardo de Irigoyen in Meija, Ramos. Rosas y su Tiempo. Buenos Aires: Atanasio Martinez, 1927, vol.II, pp.289-299

- ^ O'Donnell, Pacho (2009). Juan Manuel de Rosas, el maldito de la historia oficial. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Norma. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-987-545-555-9.

- "Los negros encontraron en el caudillo de la pampa una decidida protección: les hizo conseciones y proporcionó fondos para que se estableciesen asociaciones con la denominación de las respectivas tribus africanas a que debían su origen. Memories of Tomás de Iriarte

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército, p.546

- Doratioto (2002), p.25

- ^ Maia, p.255

- ^ Lima, p.158

- Pedrosa, p.50

- ^ Lyra (v.1), p.160

- Doratioto (2002), p.24

- ^ Doratioto (2002), p.26

- Holanda, p.113, 114

- ^ Holanda, p.116

- Vainfas, p.448

- ^ Holanda, p.114

- ^ Furtado, p.7

- Holanda, p.117

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército, p.546

- Holanda, p.119

- ^ Holanda, p.120

- Holanda, p.121

- Vainfas, p.303

- ^ Vianna, p.526

- Costa, p.145

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército, p.547

- Costa, p.146

- ^ Vianna, p.527

- Pedrosa, p.110

- Calmon (1975), p.371

- ^ Bueno, p.207

- Pedrosa, p.232

- Pedrosa, p.35

- Pedrosa, p.35 "quando o Brasil firmou-se como um país de governo sólido e situação interna estabilizada, a partir da vitória sobre a Farroupilha, em 1845, e contra a revolta pernambucana, consolidando, definitivamente, sua superioridade no continente. Compete admitir que, nesta mesma época, as novas repúblicas debatiam-se em lutas internas intermináveis iniciadas em 1810 e sofriam de visível complexo de insegurança em relação ao Brasil"

- Dolhnikoff, p.206

- Piccolo, p.43, 44

- Bueno, p.190

- Lyra (v.1), p.142

- ^ Doratioto (2002), p.28

- ^ Furtado, p.6

- ^ Furtado, p.8

- The former regent and future Marquis of Olinda.

- Lyra (v.1), p.158-162

- Calmon (1975), p.391

- Costa, p.148

- Barroso, p.119

- Furtado, p.21

- Calmon (1975), p.390

- Holanda, p.114, 115

- ^ Lima, p.159

- ^ Lyra (v.1), p.163

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército, p.547

- Golin, p.41

- ^ Furtado, p.10

- Later Viscount of Mauá.

- Calmon (1975), p.387

- Golin, p.35

- ^ Maia, p.256

- ^ Lyra (v.1), p.164

- Estado-maior do Exército, p.548

- Carvalho, p.181

- Maia, p.256, 257

- Furtado, p.9

- ^ Golin, p.22

- Pedrosa, p.229

- Carvalho, p.185,186

- ^ Costa, p.150

- Barroso, p.101

- Golin, p.23

- Golin, p.38

- ^ Maia, p.257

- Estado-maior do Exército, p.551

- Barroso, p.112

- ^ Maia, p.258

- ^ Estado-maior do Exército, p.553

- Costa, p.155, 156

- ^ Costa, p.158

- Títara, p.161

- Títara, p.161

- Estado-maior do Exército, p.554

- Magalhães, p.64

- Títara, p.162

- Calmon (1975), p.407

- Calmon (2002), p.196

- ^ Golin, p.42

- ^ Costa, p.156

- ^ Golin, p.43

- ^ Golin, p.42

- Doratioto (2009), p.80

- Golin, p.42, 43

- Calmon (2002), p.195

- Pedrosa, p.35

- Lyra (v.2), p.9 "The end of the Paraguayan War marked the apogee of the Imperial regime in Brazil. It is the 'Golden Age' of the monarchy." and "...Brazil had a reputation in the international community that, with the sole exception of the United States of America, no other country in the Americas held."

- Lyra (v.1), p.200

- Bueno, p.196

- Lyra (v.1), p.199

- Doratioto (2002), p.29

- Furtado, p.17

- Pedrosa, p.168

- ^ Furtado, p.14

- Doratioto (2002), p.95, 96

- Furtado, p.13

| Empire of Brazil | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General topics |  | ||||

| Monarchy | |||||

| Politics |

| ||||

| Military |

| ||||

| Slavery |

| ||||