| Revision as of 15:31, 23 September 2005 view sourceLexicon (talk | contribs)Administrators15,651 editsm comma changed to period in 4.76 million← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:01, 23 September 2005 view source CDThieme (talk | contribs)1,414 editsm Macedonia moved to Macedonia (region)Next edit → |

| (No difference) | |

Revision as of 20:01, 23 September 2005

For other uses, see ].

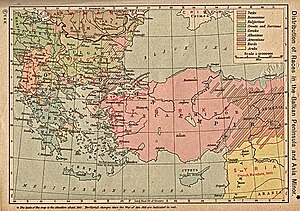

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan peninsula in south-eastern Europe with an area of about 67,000 square kilometres and a population of 4.76 million. The territory corresponds to the basins of (from west to east) the Aliákmon, Vardar/Axios and Struma/Strymon rivers (of which the Axios/Vardar drains by far the largest area) and the plains around Thessaloniki and Serres.

The region is divided between Greece, with more than half the area and population, split between the three peripheries of Central Macedonia, West Macedonia, and East Macedonia and Thrace; the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, with around 40%; and Bulgaria, with less than a tenth, in Blagoevgrad Province.

Etymology of the name of Macedonia

According to ancient Greek mythology, Macedon - ancient Greek Template:Polytonic Makedōn, poetic Template:Polytonic Makēdōn - was the name of the first phylarch (tribal chief) of the Template:Polytonic Makedónes, the part of the Template:Polytonic Makednoí tribe which initially settled western, southern and central Macedonia and founded the kingdom of Macedon. Αccording to Herodotus (Histories 8.47), the Makednoí were in turn a tribe of the Dorians. All these names are probably derived from the Doric adjective Template:Polytonic makednós (Attic Template:Polytonic mēkedanós), meaning "tall". This in turn is derived from the Doric noun Template:Polytonic mākos (Attic and modern Greek Template:Polytonic mákros and Template:Polytonic mēkos), meaning "length". Both the Macedonians (Makedónes) and their Makednoí tribal ancestors were regarded as tall people, and they are likely to have received their name on account of their height. See also List of traditional Greek place names.

Homer uses the genitive Template:Polytonic, makednēs, to describe a tall poplar tree:

- Template:Polytonic

- Template:Polytonic

- "and others weave webs, or, as they sit, twirl the yarn,

- like unto the leaves of a tall poplar tree"

- (of the female slaves of the Phaeacians, Od. 7.105f.)

It has been suggested that the name Makedónes may mean "highlanders", from a hypothetical (i.e. unattested) Macedonian bahuvrihi *Template:Polytonic *maki-kedónes "of the high earth", with the first constituent Template:Polytonic maki-, allegedly meaning "high", and an unattested second part Template:Polytonic -kedōn, being cognate to Attic Template:Polytonic khthōn, "earth". However the word Template:Polytonic has only been used to describe tall physical stature in humans, and only in two instances has it been used to mean "height" of inanimate objects: the aforementioned Homeric tall poplar tree and the imaginary wall built around the city of the Birds (in the comedy by the same name by Aristophanes). Furthermore, if the word Makikedōn actually ever existed, it should be paroxytone (Μακικέδων, as in αυτόχθων, etc), not oxytone.

Demographics

As a frontier region between several very different cultures, Macedonia has an extremely diverse demographic profile. Greeks form the majority of its population, living almost entirely in Greece. Macedonian Slavs are the second largest group in the region, forming the majority of the population in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

They consider themselves to be a distinct ethnic group, a claim controversial as many Bulgarians and Greeks believe that they are merely a subset of another people, usually the Bulgarians. They call themselves and are sometimes called by others "ethnic Macedonians" (e.g. in the former Yugoslav countries) but this term is vehemently opposed by Greeks when used to describe the Slav majority of Republic of Macedonia or a Slavic minority in northern Greece. Greece argues that this usage is inaccurate as Macedonia is in fact inhabited by a number of different peoples, none of whom has a historically exclusive claim to the term with the exception of the native Macedonians who have inhabited the region since the days of ancient Macedonia. (The question of whether the ancient Macedonians were in fact Greek is controversial, as many ancient Greeks - especially political enemies of Macedonian Kings, such as Demosthenes- regarded the Macedonians as non-Greek barbarians. On the other hand Macedonian kings regarded themselves as Greek. All inscriptions in ancient tombs and relics are in Greek related Ancient Macedonian language or in plain ancient Greek language. By 5th century BC Macedonians participated in the Olympic games adding another factor as to how they were regarded, since only Greeks were permitted to participate in the Panhellenic Games at Olympia; see the article on Macedon for more information.) The term is often used by Slavs of the region to mean the Christian Slav inhabitants of both the Republic of Macedonia and of northern Greece. Muslim Bulgarians are called Pomaks.

There is a small 3,000-strong Macedonian Slav minority in the Bulgarian region of Blagoevgrad, which is otherwise known as Pirin Macedonia. The question about the number of the Macedonian Slavs in Greek Macedonia, however, is and has been the subject of much speculation as Greece's censuses have not included the criteria of nationality and mother tongue since the 1950s. However, the Human Rights Watch released a report in 1994 estimating Macedonian Slavs around 10,000 in the region. The Greek government argues that ethnic Slavs (or of Slavic origin) inhabitants of the wider geographical region are not forming an ethnic identity, which can be solely be referred to as "Macedonian".

The other two major ethnic groups in the region are the Bulgarians, who represent the bulk of the population of Pirin Macedonia, and the Albanians, who are the majority inhabitants of the western and southwestern parts of the Republic of Macedonia and make up 25% of the population. (From CIA World Factbook)

Smaller numbers of Turks, Bosniaks, Roma, Serbs, and Vlachs may also be found in Macedonia.

Most of the inhabitants of the regions are Christians of the Eastern Orthodox rite (principally the Bulgarian Orthodox, the Greek Orthodox and the Serbian Orthodox Churches, as well as the unrecognized Macedonian Orthodox Church). There is, however, a substantial Muslim minority - principally among the Albanians, Pomaks (Muslim Bulgarians), Bosniaks, and Turks.

History

- For a more complete treatment of early Macedonia, see Macedon.

Boundaries and definitions

The name of Macedonia has not been always used with regard to the region as defined above. In its beginnings, the ancient state of Macedon encompassed only a part of this region, approximately equal to the present-day Greek Macedonia. The Roman province of Macedonia covered a much larger area than Macedon, including almost all of present-day geographical region of Macedonia, along with large parts of central Albania and Greece.

In the Byzantine empire, there was a number of different themas (provinces) dividing the geographical region of Macedonia. A thema under the name of Macedonia was, however, carved out of the original Thema of Thrace well to the east of the Struma River during the Middle Ages. This thema variously included parts of Eastern Rumelia and western Thrace within its shifting boundaries and gave its name to the Macedonian dynasty, whose founder, Emperor Basil I, was probably of Armenian descent and born near Adrianople. Hence, Byzantine documents of this era mentioning Macedonia and Macedonians actually refer to the thema by that name. The region of Macedonia (ruled by the First Bulgarian Empire throughout the 9th and the 10th century) was, on the other hand, incorporated into the Byzantine Empire in 1018 as the thema of Bulgaria.

With the conquest of the region by the Ottomans in the late 14th century and its incorporation into the Ottoman Rumili Province, the name of Macedonia disappeared as a administrative designation for several centuries and was rarely displayed on maps. The name was again revived to mean a distinct geographical region with roughly the same borders as today by European cartographers in the 19th century.

Ancient Macedonia (500 BC to 146 BC)

Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since Neolithic times. Its recorded history began with the emergence of the ancient kingdom of Macedon in what is now the Greek part of Macedonia and the neighbouring Bitola district in the south of today's Republic of Macedonia. By 500 BC, the early Macedonian kingdom had become subject to the Persian Empire but played no significant part in the wars between the Persians and the Greeks.

King Alexander I of Macedon (died 450 BC) was the first Macedonian king to play a significant role in Greek politics, promoting the adoption of the Attic dialect and culture. The Hellenic character of Macedon grew over the next century until, under the rule of Philip II of Macedon, Macedon extended its power in the 4th century BC over the rest of northern Greece. Philip's son Alexander the Great created an even bigger empire, not only conquering the rest of Greece but also seizing control of the Persian Empire, Egypt and lands as far east as the fringes of India.

Much of the impetus towards the creation of this common identity was provided by Alexander the Great. Alexander's conquests produced a lasting extension of Greek culture and thought across the ancient Near East, but his empire broke up on his death. His generals divided the empire between them, founding their own states and dynasties - notably Antigonus I, Antipater, Lysimachus, Perdiccas, Ptolemy I, and Seleucus I. Macedon itself was taken by Cassander, who ruled it until his death in 297 BC. Antigonus II took control in 277 BC following a period of civil strife. During his long reign, which lasted until 239 BC, he successfully restored Macedonian prosperity despite losing many of the subjugated Greek city-states. His successor Antigonus III (reigned 229 BC-221 BC) re-established Macedonian power across the region.

Macedon sovereignty was brought to an end at the hands of the rising power of Rome in the 2nd century BC. Philip V of Macedon took his kingdom to war against the Romans in two wars during his reign (221 BC-179 BC). The First Macedonian War (215 BC-205 BC) was fairly successful for the Macedonians but Philip was decisively defeated in the Second Macedonian War in (200 BC-197 BC). Although he survived war with Rome, his successor Perseus of Macedon (reigned 179 BC-168 BC) did not; having taken Macedon into the Third Macedonian War in (171 BC-168 BC), he lost his kingdom and his life when he was defeated. Macedonia was initially divided into four republics subject to Rome before finally being annexed in 146 BC as the first Roman province.

Medieval Macedonia

With the division of the Roman Empire into west and east in 395 AD, Macedonia came under the rule of Rome's Byzantine successors. Whereas the Byzantine state's prevailing Greek culture flourished in Thessaloniki and the Aegean Sea littoral, the rest of Macedonia was settled from around 600 AD by Slavs, with Slavic tribes reaching as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese. The bulk of the Slavs settled in the north of the region but substantial Slavic populations also settled in what is now the northern part of Greek Macedonia. The population of the entire region was, however, severely depleted by destructive invasions of Visigoths, Huns, and Vandals.

In the 5th and the 6th centuries, a number of Slavic tribes settled in Macedonia, Central Hellas, Thessaly and Peloponnesos. They were referred to by Byzantine historians as "Sklavines". The Sklavines represented a solid mass in most of inland Macedonia but in the Aegean sea littoral, Thessaly and Peloponnesos they lived alongside the indigenous Greek population. Although the Sklavines participated in several assaults against the Byzantine Empire - alone or aided by Bulgars or Avars, they generally recognised the authority of the Byzantine emperor until 837 AD, when most of inland Macedonia was incorporated into Bulgaria by Bulgarian Khan Presian. There are no Byzantine records of "Sklavines" after 836/837 as the Slavs of inland Macedonia became gradually Bulgarized, while those living in the Aegean sea littoral, the Chalcidice peninsula and inland Greece were assimilated by the indigenous Greek population.

At the end of the 10th century Macedonia turned into the political and cultural centre of Bulgaria as Byzantine emperor Basil II conquered the eastern part of the country, including the capital of Preslav, in 972. A new capital was established at Ohrid, which also became the seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. After several decades of almost incessant war, Bulgaria fell under Byzantine rule in 1018. The whole of Macedonia was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire as the province of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced in rank to an archbishopric.

In the 13th and 14th century Byzantine control was punctuated by periods of Bulgarian and Serbian rule in the north. Conquered by the Ottoman army in the first half of the 15th century, Macedonia remained a part of the Ottoman Empire for nearly 500 years, during which it gained a substantial Turkish minority. (Thessaloniki later becomes the home of a large Jewish population following Spain's expulsions of Jews after 1492.)

Macedonia's Division

After the revival of Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian statehood in the 19th century, Macedonia became a focus of the national ambitions of all three governments, leading to the creation in the 1890s and 1900s of rival armed groups who divided their efforts between fighting the Turks and one another. The most important of these was the Bulgarian-sponsored Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), under Goce Delchev who in 1903 rebelled in the so-called Ilinden uprising, and the Greek efforts from 1904 till 1908 (Greek Struggle for Macedonia). Diplomatic intervention by the European powers led to plans for an autonomous Macedonia under Ottoman rule.

The rise of the Albanian and the Turkish nationalism after 1908, however, prompted Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria to bury their differences with regard to Macedonia and to form a joint coalition against the Ottoman Empire in 1912. Disregarding public opinion in Bulgaria, which was in support of the establishment of an autonomous Macedonian province under a Christian governor, the Bulgarian government entered a pre-war treaty with Serbia which divided the region into two parts. The part of Macedonia west and north of the line of partition was contested by both Serbia and Bulgaria and was subject to the arbitration of the Russian Tsar after the war. Serbia formally renounced any claims to the part of Macedonia south and east of the line, which was declared to be within the Bulgarian sphere of interest. The pre-treaty between Greece and Bulgaria, however, did not include any agreement on the division of the conquered territories - evidently both countries hoped to occupy as much territory as possible having their sights primarily set on Thessaloniki.

In the First Balkan War, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro occupied almost all Ottoman-held territories in Europe. Bulgaria bore the brunt of the war fighting on the Thracian front against the main Ottoman forces. Both her war expenditures and casualties in the First Balkan War were higher than those of Serbia, Greece and Montenegro combined. Macedonia itself was occupied by Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian forces. The Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of London in May 1913 assigned the whole of Macedonia to the Balkan League, without, specifing the division of the region, in order to promote problems between the allies. Dissatisfied with the creation of an autonomous Albanian state, which denied her access to the Adriatic, Serbia asked for the suspension of the pre-war division treaty and demanded from Bulgaria greater territorial concessions in Macedonia. Later in May the same year, Greece and Serbia signed a secret treaty in Thessaloniki stipulating the division of Macedonia according to the existing lines of control. Both Serbia and Greece, as well as Bulgaria, started to prepare for a final war of partition.

In June 1913, Bulgarian Tsar Ferdinand, without consulting the government, and without any declaration of war, ordered Bulgarian troops to attack the Greek and Serbian troops in Macedonia, initiating the Second Balkan War. The Bulgarian army was in full retreat in all fronts. The Serbian army chose to stop its operations when achieved all its territorial goals and only then the Bulgarian army took a breath. During the last 2 days the Bulgarians managed to achieve a defensive victory against the advancing Greek army in the Kresna Gorge. However at the same time the Romanian army crossed the undefended northern border and easily advanced towards Sofia. Romania interefered in the war, in order to satisfy it's territorial claims against Bulgaria. The Ottoman Empire also interfered, easily reasumming control of Eastern Thrace with Edirne. The Second Balkan War, also known as Inter-Ally War, left Bulgaria only with the Struma valley and a small part of Thrace with minor ports at the aegean sea. Vardar Macedonia was incorporated into Serbia and thereafter referred to as South Serbia. Southern (Aegean) Macedonia was incorporated into a Greece. The region suffered heavily during the Second Balkan War. During its advance at the end of June, the Greek army set fire to the Bulgarian quarter of the town of Kukush (Kilkis) and over 160 Bulgarian villages around Kukush and Serres driving some 50,000 refugees into Bulgaria proper. The Bulgarian army retaliated by burning the Greek quarter of Serres and by arming Muslims from the region of Drama which led to a massacre of Greek civilians.

In September of 1915, the Greek government allowed the landing of the troops of the Allies in Thessaloniki.In 1916 the pro-German King of Greece agreed with the Germans to allow military forces of the Central Powers enter Greek Macedonia in order to attack the forces of the Allies in Thessaloniki. As a result of that Bulgarian troops occupied the eastern part of Greek Macedonia with the port of Kavala. The region was, however, restored to Greece following the victory of the Allies in 1918. After the destruction of the Greek Army in Asia Minor in 1922 Greece and Turkey exchanged most of Macedonia's Turkish minority and the Greek inhabitants of Thrace and Anatolia, as a result of which Aegean Macedonia experienced a large addition to its population and became overwhelmingly Greek in ethnic composition. Serbian-ruled Macedonia was incorporated with the rest of Serbia into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) in 1918. Yugoslav Macedonia was subsequently subjected to an intense process of "Serbianization" during the 1920s and 1930s.

During World War II the boundaries of the region shifted yet again. When the German forces occupied the area, most of Yugoslav Macedonia and part of Greek Macedonia were transferred for administration to Bulgaria. During the Bulgarian admininstration of Eastern Greek Macedonia, some 100,000 Bulgarian refugees from the region were resettled there and perhaps as many Greeks were deported or fled to Greece. Western Greek Macedonia was occupied by Italy, with the western parts of Yugoslav Macedonia being annexed to Italian-occupied Albania. The remainder of Greek Macedonia (including all of the coast) was occupied by Nazi Germany. One of the worst episodes of the Holocaust happened here when 60,000 Jews from Thessaloniki were deported to extermination camps in occupied Poland. Only a few thousand survived.

Macedonia was liberated in 1944, when the Red Army's advance in the Balkan Peninsula forced the German forces to retreat. The pre-war borders were restored under U.S. and British pressure because the Bulgarian government was insisting to keep its military units on Greek soil. The Bulgarian Macedonia returned fairly rapidly to normality, but the Bulgarian patriots in Yugoslav Macedonia underwent a process of ethnic cleansing by the Belgrade authorities, and Greek Macedonia was ravaged by the Greek Civil War, which broke out in December 1944 and did not end until October 1949.

After this civil war, a large number of former ELAS fighters who took refuge in communist Bulgaria and Yugoslavia and described themselves as "ethnic Bulgarian/Macedonian" were prohibited from reestablishing to their former estates by the Greek authorities. Most of them were accused in Greece for crimes committed during the period of the German occupation.

Macedonia after World War II

The Yugoslav communist leader Josip Broz Tito separated Yugoslav Macedonia from Serbia after the war. It became a republic of the new federal Yugoslavia (as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia) in 1946, with its capital at Skopje. Tito also promoted the concept of a separate Macedonian nation, as a means of severing the ties of the Slav population of Yugoslav Macedonia with Bulgaria. Although the Macedonian language is very close to Bulgarian, the differences were deliberately emphasized and the region's historical figures were promoted as being uniquely Macedonian (rather than Serbian or Bulgarian). A separate Macedonian Orthodox Church was established, splitting off from the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Communist Party sought to deter pro-Bulgarian sentiment, which was punished severely; convictions were still being handed down as late as 1991.

Tito had a number of reasons for doing this. First, he wanted to reduce Serbia's dominance in Yugoslavia; establishing a territory formerly considered Serbian as an equal to Serbia within Yugoslavia achieved this effect. Secondly, he wanted to sever the ties of the Macedonian Slav population with Bulgaria as recognition of that population as Bulgarian would have undermined the unity of the Yugoslav federation. Third of all, Tito sought to justify future Yugoslav claims towards the rest of Macedonia (Pirin and Aegean), in the name of the "liberation" of the region. The potential "Macedonian" state would remain as a constituent republic within Yugoslavia, and so Yugoslavia would manage to get access to the Aegean Sea.

Tito's designs on Macedonia were asserted as early as August, 1944, when in a proclamation he claimed that his goal was to reunify "all parts of Macedonia, divided in 1915 and 1918 by Balkan imperialists". To this end, he opened negotiations with Bulgaria for a new federal state, which would also probably have included Albania, and supported the Greek Communists in the Greek Civil War. The idea of reunification of all of Macedonia under Communist rule was abandoned as late as 1949 when the Greek Communists lost and Tito fell out with the Soviet Union and pro-Soviet Bulgaria.

Across the border in Greece, Macedonian Slavs were seen as a potentially disloyal "fifth column" within the Greek state. The existence of a Slav minority was officially denied, with Macedonian Slavs referred to in official censuses as being merely "Slavophone" Greeks. Slavonic names were forbidden, and a strip along the border (where most of the Macedonian Slavs of Greece still live) was subjected to security restrictions. Greeks were resettled in the region to dilute the Slav population, many of whom emigrated (especially to Australia) in the face of official pressure. Although there was some liberalization between 1959 and 1967, the Greek military dictatorship re-imposed harsh restrictions. The situation gradually eased after Greece's return to democracy, although even as recently as the 1990s Greece has been criticised by international human rights activists for "harassing" Macedonian Slav political activists. Elsewhere in Greek Macedonia, economic development after the war was brisk and the area rapidly became the most prosperous part of the region. The coast was heavily developed for tourism, particularly on the Khalkidhiki peninsula.

Bulgaria initially accepted the existence of a distinctive Macedonian identity, but it was under Soviet and Yugoslav pressure. It had been agreed that Pirin Macedonia would join Yugoslavian Macedonia and for this reason the population was forced to declare itself "Macedonian" in the 1946 census. This caused resentment and many people were imprisoned or interned in rural areas outside Macedonia. After Tito's split from the Soviet bloc this position was abandoned and the existence of a Macedonian nation or language was denied.

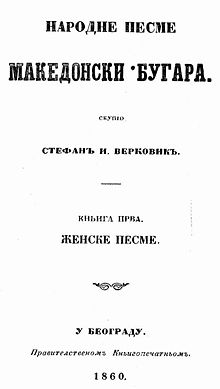

Attempts of Macedonian Slav historians after the 1940s to claim a number of prominent figures of the 19th century Bulgarian cultural revival and armed resistance movement as Macedonian Slavs has caused ever since a bitter resentment in Sofia. Bulgaria has repeatedly accused the Republic of Macedonia of appropriating Bulgarian national heroes and symbols and of editing works of literature and historical documents so as to prove the existence of a Macedonian Slav consciousness before the 1940s. The publication in the Republic of Macedonia of the folk song collections 'Bulgarian Folk Songs' by the Miladinov Brothers and 'Songs of the Macedonian Bulgarians' by Serbian archaelogist Verkovic under the "politically correct" titles 'Collection' and 'Macedonian Folk Songs' are some of the examples quoted by the Bulgarians. The issue has soured the relations of Bulgaria with former Yugoslavia and later with the Republic of Macedonia for decades.

Independence of the Republic of Macedonia

Kiro Gligorov, the president of Yugoslav Macedonia, sought to keep his republic outside the fray of the Yugoslav wars in the early 1990s. Yugoslav Macedonia's very existence had depended on the active support of the Yugoslav state and Communist Party. As both began to collapse, the Macedonian Slav authorities allowed and encouraged a stronger assertion of Macedonian Slav national identity than before. This included toleration of demands from Macedonian Slav nationalists for the reunification of Macedonia.

In 1991, Yugoslav Macedonia held a referendum on independence which produced an overwhelming majority in favour, although it was boycotted by the ethnic Albanians. The republic seceded peacefully from the Yugoslav federation, declaring its independence as the Republic of Macedonia. The move received, however, the support only of Bulgaria. The Bulgarians were hoping that the independence of the Republic of Macedonia would reduce Serbian influence in the country and would eventually lead to the "re-Bulgarisation" of its population. Bulgaria was consequently the first country to officially recognise Republic of Macedonia independence - as early as February 1992. However, the Bulgarians refused and have refused so far to recognise the existence of a separate Macedonian language and a separate Macedonian Slav nation.

All other neighbours and even some of the national minorities within the Republic gave, however, a rather cold welcome to its independence. The Macedonian Albanians were unhappy about an erosion of their national rights in the face of a more assertive Macedonian Slav nationalism. Some nationalist Serbs called for the republic's reincorporation into Serbia, although in practice this was never a likely prospect, given Serbia's preoccupation with Bosnia and Croatia. The strongest reaction by far, however, was in Greece.

Controversy: Republic of Macedonia and Greece

Although there is no controversy that some of the area occupied by the modern Republic of Macedonia was indeed part of the ancient Macedonian kingdom, the antecedents of the Slavic people that populate it did not arrive in the Balkans until 1000 years after that period. Because of that, and as had happened in Bulgaria, the appropriation of ancient Greek symbols by Slavic people in Macedonia was the cause of nationalist anger for many years. This anger was reinforced by the legacy of the Civil War and the view in many quarters that Greece's Macedonian Slavs were a "disloyal" minority. The Republic of Macedonia's status became a heated political issue in Greece, where huge demonstrations took place in Athens and Thessaloniki in 1992 against the new state, under the slogan "Macedonia is Greek." The Greek government objected formally to any use of the name Macedonia (including any derivative names), and also to the use of symbols such as the Star of Vergina.

The controversy was not just nationalist, but had much to do with internal Greek politics as well. The two leading Greek political parties, the ruling conservative New Democracy under Constantine Mitsotakis and the socialist PASOK under Andreas Papandreou, sought to outbid each other in whipping up nationalist sentiment against the Republic of Macedonia. To complicate matters further, New Democracy itself was divided; Mitsotakis favoured a compromise solution on the Macedonian question, while his foreign minister Adonis Samaras took a hard-line approach. The two eventually fell out and Samaras was sacked, with Mitsotakis reserving the foreign ministry for himself. He failed to reach an agreement on the Macedonian issue despite United Nations mediation and fell from power in October 1993, largely as a result of his handling of the issue.

When Papandreou took power following the October 1993 elections, he restated his party's hard line position on the issue. The United Nations recommended recognition of the Republic of Macedonia under the temporary name of the "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (or FYROM for short), which would be used externally while the country continued to use "Republic of Macedonia" as its constitutional name. The United States and European Union agreed to this proposal and duly recognised it, prompting huge demonstrations in Greek cities against what was termed a "betrayal" by Greece's allies. Papandreou supported and encouraged the demonstrations, boosting his own popularity by taking an increasingly hard line against the Republic of Macedonia. In February 1994, he imposed a total embargo on the country, with the exception of food and medicines. The effect on the FYROM economy was devastating. The blockade also had a political cost for Greece, as there was little understanding or sympathy for the country's position - and exasperation over what was seen as Greek obstructionism - from some of its European Union partners. Greece was criticised in some quarters for contributing to the rising tension in the Balkans, even if the wars in the former Yugoslavia were widely seen as having been triggered by the premature recognition of its successor republics, a move to which Greece had objected from the beginning. It later emerged that Greece had only agreed to the dissolution of Yugoslavia in return for EU solidarity on the Macedonian issue. In 1994, the European Commission took Greece to the European Court of Justice in an effort to overturn the embargo, but the court provisionally ruled in Greece's favour and the embargo was lifted by Athens the following year before a final verdict was reached.

Political pressure from inside and outside Greece did eventually lead to a temporary settlement of the issue. An "interim agreement" was signed by the two countries in September 1995, brokered by UN special envoy Cyrus Vance. International pressure on the government in Skopje led it to agree to remove any implied territorial claims to the greater Macedonia region from its constitution and to drop the Star of Vergina from its flag. In return, Greece lifted the blockade.

Discussions continue over the Greek objection regarding the country's name, but without any resolution so far. Outside Greece and international diplomatic settings, the country is usually simply called "Macedonia". About 40 countries, notably the United States, People's Republic of China and Russian Federation, have recognised it by its constitutional name, while the remaining majority of countries, the United Nations and other international organisations recognize it as the "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", often abbreviated as "FYROM".

Controversy: Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria

Bulgarian governments throughout the period continued their policy of non-recognition of Macedonian Slavs as a distinct ethnic group. There were repeated complaints of official harassment of Macedonian Slav activists in the 1990's. Attempts of Slav Macedonian separatist organisation UMO Ilinden to commemorate the grave of revolutionary Yane Sandanski throughout the 1990's were usually hampered by the Bulgarian police. Several incidents of mobbing of UMO Ilinden members by Bulgarian IMRO activists were also reported. After the Bulgarian Electoral Committee endorsed in 2001 the registration of a wing of UMO Ilinden, which had dropped separatist demands from its Charter, the mother organisation became largely inactive. No major incidents or harassment has been reported since then.

Similar cases of harassment of pro-Bulgarian organisations and activists have been reported in the Republic of Macedonia. In 2000 several teenagers threw smoke bombs at the conference of pro-Bulgarian organisation 'Radko' in Skopje causing panic and confusion among the delegates. The perpetrators were afterwards acclaimed by the Macedonian press as national heroes. 'Radko' was later banned by the Macedonian Constitutional Court as separatist. The organisation has continued its activity, though mostly in the cultural field.

In 2001 'Radko' issued in Skopje the original version of the folk song collection 'Bulgarian Folk Songs' by the Miladinov Brothers (issued under an edited name in the Republic of Macedonia and viewed as a collection of Slav Macedonian lyrics). The book triggered a wave of other publications, among which the memoirs of the Greek bishop of Kastoria, in which he talked about the Greek-Bulgarian church struggle at the beginning of the 20th century, as well the Report of the Carnegie Commission on the causes and conduct of the Balkan Wars from 1913. Neither of these addressed the Slavic population of Macedonia as Macedonian Slav but as Bulgarian. Being the first publications to question the official Macedonian position of the existence of a distinct Macedonian Slav identity going back to the time of Alexander the Great, the books triggered a reaction of shock and disbelief in Macedonian Slav public opinion. The scandal after the publication of 'Bulgarian Folk Songs' resulted in the sacking of the Macedonian Minister of Culture, Dimitar Dimitrov.

As from 2000, Bulgaria started to grant Bulgarian citizenship to members of the Bulgarian minorities in a number of countries, including the Republic of Macedonia. The vast majority of the applications have been from Macedonian citizens. As at May, 2004, some 14,000 Macedonian Slavs had applied for a Bulgarian citizenship on the grounds of Bulgarian origin and 4,000 of them had already received their Bulgarian passports. The main reason behind this was the posibility to travel in European Union and other countries without need of a visa, which is still not possible having only the Macedonian passport. In June, 2004, the Macedonian state television announced with alarm that at least one member of every fourth household in the eastern part of the Republic of Macedonia had already received a Bulgarian passport or had at least applied for one. The last quoted number so far was of 63,000 Macedonian Slavs (the number has not been confirmed officially) by the Macedonian daily Vecher on April 5, 2005.

See also

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Macedonia (Greece)

- Pirin Macedonia

- Republic of Macedonia

- History of Europe

- History of the Balkans

- History of Greece

- History of Bulgaria

- History of the Republic of Macedonia

- History of Serbia

External links

- History of Macedon

- Herodotus on the origins of the Makednoí

- Macedonia, The Historical Profile - Greek perspective

- http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr - Greek perspective

- http://makedonija.150m.com/./ - Original Documents and Maps regarding Macedonia, Pro-Bulgarian

- http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/ - Macedonian Slav perspective

- http://www.mymacedonia.net/ - Macedonian Slav perspective

- http://www.macedonia-info.org/history/ - Macedonian Slav perspective

Template:Roman provinces 120 AD

Categories: