| Revision as of 09:25, 22 August 2008 editGwinva (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers9,981 editsm reduce overlinking← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:28, 22 August 2008 edit undoGwinva (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers9,981 editsm →Types of horses used in warfare: though it pains me to do it, changed armour to armor; US spelling used elsewhereNext edit → | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| ==Types of horses used in warfare== | ==Types of horses used in warfare== | ||

| War horses varied in size and build depending on the work performed, the weight a horse needed to carry or pull, and distances traveled. A fundamental principle of ] is "form to function." Therefore, the type of horse used for various forms of warfare depended on the task at hand.<ref>Bennett, ''Conquerors'' p. 31</ref> Weight carried affects speed and endurance, creating a trade-off: |

War horses varied in size and build depending on the work performed, the weight a horse needed to carry or pull, and distances traveled. A fundamental principle of ] is "form to function." Therefore, the type of horse used for various forms of warfare depended on the task at hand.<ref>Bennett, ''Conquerors'' p. 31</ref> Weight carried affects speed and endurance, creating a trade-off: armor added protection,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medieval-castle-siege-weapons.com/history-of-medieval-armor.html |title=History of Medieval Armor - Protection Was Everything| author=Benjamin, Garfield|accessdate=2008-08-07|publisher=medieval-castle-siege-weapons.com}}</ref> but added weight reduces maximum speed, as is seen today when ] modern ].<ref name=Ainslie227>Ainslie ''Complete Guide'' pp. 227-228</ref> Therefore, various cultures had different military needs to consider when balancing the inverse relationship of weight and speed. In some situations, one primary type of horse was favored over all others.<ref>Edwards, ''The Arabian,'' p. 19</ref> In other places, multiple types were needed; warriors would travel to battle riding a lighter horse of greater speed and endurance, and then switch to a heavier horse, with greater weight-carrying capacity, when wearing heavy armor in actual combat.<ref name=NicolleCK14>Nicolle ''Crusader Knight'' p. 14</ref> | ||

| The average horse can carry up to approximately 30% of its body weight, depending on bone size.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://aerc.org/AERC_Rider_Handbook110303.asp|title=Chapter 3, Section IV: Size|author=American Endurance Ride Conference|accessdate=2008-08-07|date= Nov. 2003|work=Endurance Rider's Handbook|publisher=AERC}}</ref> While all horses can pull more than they can carry, the weight horses can pull varies widely, depending on the build of the horse, the type of vehicle, road conditions, and other factors.<ref>Baker, ''A Treatise on Roads and Pavements'', pp. 22-23</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://horsepullresults.com/LacledeCountyFairgroundsarticle.asp|title=Mighty horses pull more than their weight at fair|author=Luthy, Dusty|accessdate=2008-08-08|work=The Lebanon Daily Record|publisher=Horsepull Results}}</ref> The method by which a horse was hitched to a vehicle also influenced how much it could pull: |

The average horse can carry up to approximately 30% of its body weight, depending on bone size.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://aerc.org/AERC_Rider_Handbook110303.asp|title=Chapter 3, Section IV: Size|author=American Endurance Ride Conference|accessdate=2008-08-07|date= Nov. 2003|work=Endurance Rider's Handbook|publisher=AERC}}</ref> While all horses can pull more than they can carry, the weight horses can pull varies widely, depending on the build of the horse, the type of vehicle, road conditions, and other factors.<ref>Baker, ''A Treatise on Roads and Pavements'', pp. 22-23</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://horsepullresults.com/LacledeCountyFairgroundsarticle.asp|title=Mighty horses pull more than their weight at fair|author=Luthy, Dusty|accessdate=2008-08-08|work=The Lebanon Daily Record|publisher=Horsepull Results}}</ref> The method by which a horse was hitched to a vehicle also influenced how much it could pull: horses could pull greater weight with a ] than they could with an ox ] or a breast collar.<ref name=Chamberlin106>Chamberlin ''Horse'' pp. 106-110</ref> Horses ] to a wheeled vehicle on a paved road can pull as much as eight times their weight,<ref name=dynamometer>{{cite web|url=http://www.easterndrafthorse.com/History/historydyn.htm|title= History of the draft horse dynamometer machine|author=Eastern Draft Horse Association|work=History|publisher=Eastern Draft horse Association|accessdate=2008-07-17}}''Note: Traction force of horses pulling a load, as measured by a ], can be between 50 and 300 ], depending on speed and distance.''</ref> but far less if pulling wheel-less loads over unpaved terrain.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.easterndrafthorse.com/Rules/EDHARules.htm|title=Eastern Draft Horse Association Rules|author=Eastern Draft Horse Association|work=History|publisher=Eastern Draft horse Association|accessdate=2008-07-17}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.horsepull.com/Record%20Loads.htm|title=Reords|author=Horsepull.com|work=|publisher=Horsepull.com|accessdate=2008-08-07}}</ref> Thus, horses used for pulling vehicles varied in size, and, like riding animals, had to make a trade-off between speed and weight. Light horses could pull a small war chariot at speed.<ref>Edwards, ''The Arabian'', pp. 9-11</ref> On the other hand, supply wagons and other support vehicles needed either heavier horses or a larger number of horses to perform the transportation duties required support military operations.<ref name=Chamberlin146>Chamberlin ''Horse'' p. 146</ref> | ||

| ===Light-weight === | ===Light-weight === | ||

Revision as of 09:28, 22 August 2008

"War horse" redirects here. For other uses, see War horse (disambiguation).

Horses were first used in warfare over 5,000 years ago. The earliest evidence of the use of horses ridden in warfare dates from Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine pulling wagons, and by 1600 BC, harness and chariot designs had improved to the point that chariot warfare was common throughout the Ancient Near East. The earliest written training manual for war horses was a guide for training chariot horses written about 1350 BC. As formal cavalry tactics replaced the chariot, so did the need for new training methods, and by 360 BC, the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon had written an extensive treatise on horsemanship. The effectiveness of horses in battle was also revolutionized by improvements in technology, including the invention of the saddle, the stirrup, and later, the horse collar.

Many different types and sizes of horses were used in war, depending on the form of warfare. The type used varied with whether the horse was being ridden or driven, and whether they were being used for reconnaissance, cavalry charges, raiding or communication. Throughout history, mules and donkeys as well as horses played a crucial role in providing supplies to armies in the field.

Horses were well suited to the warfare tactics of the nomadic cultures from the steppes of Central Asia. Cavalry made up a large part of the armies of the Huns that invaded Europe and the Mongols that conquered much of Eurasia. The cultures of India and Japan made extensive use of cavalry, while the Chinese relied heavily upon chariots until adopting cavalry tactics to a limited degree, beginning in the 4th century BC. Muslim warriors relied upon light cavalry in their campaigns throughout North Africa, Asia and Europe beginning in the 7th and 8th centuries AD.

Europeans bred several types of war horses in the Middle Ages, used extensively for all types of warfare, and the best-known heavy cavalry warrior of the period was the armoured Knight. With the decline of the knight and rise of gunpowder in warfare, light cavalry again rose to prominence, and was used in both European warfare and in the conquest of the Americas. In the Americas, the use of horses and development of mounted warfare tactics were learned by the indigenous people, particularly by the highly skilled horse-mounted warriors of the Native American nations in the American West during the 19th century.

Light cavalry was seen on the battlefield well into the 20th century. Horse cavalry began to be phased out after World War I in favor of tank warfare, though a few horse cavalry units were still in use during World War II. By the end of World War II, horses were seldom seen in battle, but were still used extensively for the transport of troops and supplies. Today, formal horse cavalry units have almost disappeared, although horses are still seen in use by organized armed fighters in third world countries. Many nations still maintain small units of mounted men for use in patrol and reconnaissance, and cavalry units are also used for ceremonial, exhibition and education purposes in many areas. Horses are also used today for historical reenactment of battles, law enforcement, public safety work, and in equestrian competitions that have developed from the skills and training tactics once required by the military.

Types of horses used in warfare

War horses varied in size and build depending on the work performed, the weight a horse needed to carry or pull, and distances traveled. A fundamental principle of horse conformation is "form to function." Therefore, the type of horse used for various forms of warfare depended on the task at hand. Weight carried affects speed and endurance, creating a trade-off: armor added protection, but added weight reduces maximum speed, as is seen today when handicapping modern race horses. Therefore, various cultures had different military needs to consider when balancing the inverse relationship of weight and speed. In some situations, one primary type of horse was favored over all others. In other places, multiple types were needed; warriors would travel to battle riding a lighter horse of greater speed and endurance, and then switch to a heavier horse, with greater weight-carrying capacity, when wearing heavy armor in actual combat.

The average horse can carry up to approximately 30% of its body weight, depending on bone size. While all horses can pull more than they can carry, the weight horses can pull varies widely, depending on the build of the horse, the type of vehicle, road conditions, and other factors. The method by which a horse was hitched to a vehicle also influenced how much it could pull: horses could pull greater weight with a horse collar than they could with an ox yoke or a breast collar. Horses harnessed to a wheeled vehicle on a paved road can pull as much as eight times their weight, but far less if pulling wheel-less loads over unpaved terrain. Thus, horses used for pulling vehicles varied in size, and, like riding animals, had to make a trade-off between speed and weight. Light horses could pull a small war chariot at speed. On the other hand, supply wagons and other support vehicles needed either heavier horses or a larger number of horses to perform the transportation duties required support military operations.

Light-weight

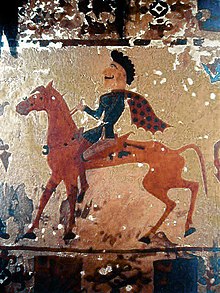

Light, "oriental" horses such as the ancestors of the modern Arabian, Barb, and Akhal-Teke were used for warfare that required speed, endurance and agility. Such horses ranged from about 12 hands to just under 15 hands (48 to 60 inches (1.2 to 1.5 m)), weighing approximately 800 to 1,000 pounds (360 to 450 kg). To move quickly, riders had to use lightweight tack and carry relatively light weapons such as bows, light spears, javelins, or, later, rifles. This was the original horse used for the earliest chariot warfare, raiding, and light cavalry.

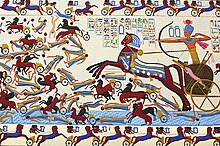

Light horses were used by many cultures, including the Scythians, the Ancient Egyptians, the Mongols, the Arabs, and the American Indians. Throughout the Ancient Near East, small, light animals were used to pull chariots designed to carry no more than two passengers, a driver and a warrior. In the European Middle Ages, one light type of horse became known as a palfrey, another was the rouncey.

Medium-weight

Medium-weight horses developed as early as the Iron Age with the needs of various civilizations to pull heavier loads, such as chariots capable of holding more than two people, and, as light cavalry evolved into heavy cavalry, to carry heavily-armoured riders. Larger horses were also needed to pull supply wagons, and to maneuver various types of weapons, such as horse artillery, into place. Medium-weight horses had the greatest range in size, from about 14.2 hands but stocky, to as much as 16 hands (58 to 64 inches (1.5 to 1.6 m)), weighing approximately 1,000 to 1,200 pounds (450 to 540 kg). They generally were quite agile in combat, though they did not have the raw speed or endurance of a lighter horse. By the Middle Ages, heavier horses in this class were sometimes called destriers. They may have resembled modern Baroque or heavy warmblood breeds. Later, horses similar to the modern warmblood often carried European cavalry.

Heavy-weight

Large, heavy horses, weighing from 1,500 to 2,000 pounds (680 to 910 kg), the ancestors of today's draft horses, were used, particularly in Europe, from the Middle Ages onward. They pulled heavy loads, having the muscle power to pull weapons or supply wagons and to remain calm under fire. Some historians believe they may also have carried the heaviest-armoured knights of the European Late Middle Ages though others dispute this claim, indicating that the destrier, or knight's battle horse, was a medium-weight animal. Breeds at the smaller end of the heavyweight category may have included the ancestors of the Percheron, which are agile for their size and would have been physically able to maneuver in battle. However, there is also considerable dispute if the destier class of horse actually included draft types.

Other equids

Horses were not the only equids used to support human warfare. Donkeys were often used as pack animals to carry gear for non-mounted units. Mules were also commonly used, especially as pack animals and to pull wagons, but also occasionally as riding animals. Because mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses, they were particularly useful for strenuous, difficult support tasks, particularly hauling food and supplies over difficult terrain. The size of a mule and work to which it was put depended largely on the breeding of the mare that produced the mule. Mules, like horses, could be lightweight, medium weight, or even, when produced from draft horse mares, of moderate heavy weight.

Training and deployment

- See also Horse training

The oldest manual on training horses for chariot warfare was written circa 1350 BC by the Hittite horsemaster, Kikkuli. An ancient manual on the subject of training riding horses, particularly for the Ancient Greek cavalry is Hippike (On Horsemanship) written about 360 BC by the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon. One of the earliest texts from Asia was that of Kautilya, written about 323 BC.

Whether horses were trained for pulling chariots, to be ridden as light cavalry, heavy cavalry, or as the destrier for the heavily-armoured knight, much training was required to overcome the horse's natural instinct to flee from noise, the smell of blood, the confusion of combat, and learn to accept any sudden or unusual movements of their riders when utilizing a weapon or avoiding one. Developing balance and agility was crucial. The origins of the discipline of Dressage came from the need to train horses to be both obedient and maneuverable. The Haute ecole or "High School" movements of classical dressage taught to the Lipizzan horses at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna have their roots in maneuvers needed on the battlefield. However, modern airs above the ground were unlikely to have been used in actual combat, as most would have exposed the unprotected underbelly of the horse to the weapons of foot soldiers.

In most cultures, a war horse used as a riding animal was trained to be controlled with limited use of reins, responding primarily to the rider's legs and weight; to become accustomed to any necessary tack and protective armour placed upon it, as well as learn to balance under a rider who would also be laden with weapons and armour. Horses used for chariot warfare were not only trained for combat conditions, but because many chariots were pulled by a team of two to four horses, they also had to learn to work together with other animals in close quarters under chaotic conditions. A horse used in close combat may have been taught, or at least permitted, to kick, strike and even bite, thus becoming weapons in the extended arsenal of the warriors they carried.

Technological innovations

Horses were probably ridden in prehistory before they were driven. However, evidence is scant, mostly consisting of simple images of human figures on horse-like animals drawn on rock or clay. The earliest tools used to control horses were, Bridles of various sorts, which were invented nearly as soon as the horse was domesticated. Evidence of bit wear appeared on the teeth of horses at the archaeology sites of Botai and Kozhai 1 in northern Kazakhstan, as early as 3500-3000 BC.

Harness and vehicles

Main articles: Chariot, Horse collar, and Horse harness

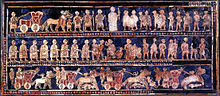

The invention of the wheel was a major technological innovation that gave rise to chariot warfare. Initially, as illustrated by the Standard of Ur, in ancient Sumer, c. 2500 BC, equines, either horses or onagers, were hitched to wheeled carts with a yoke around their necks, in a manner similar to that of oxen. However, such a design is incompatible with horse anatomy, limiting both the strength and mobility of the horse. By the time of the Hyksos invasions of Egypt, c. 1600 BC, horses were pulling chariots with an improved harness design that made use of a breast collar and breeching, which allowed a horse to move faster and pull more weight.

Even after the chariot had become obsolete as a tool of war, there still was a need for technological innovations in pulling technologies as larger horses were needed to pull heavier loads of both supplies and weapons. The invention of the horse collar in China during the 5th century AD (Southern and Northern Dynasties) allowed horses to pull greater weight than they could when hitched to a vehicle by means of the ox yokes or breast collars used in earlier times. The horse collar arrived in Europe during the 9th century, and became widespread throughout Europe by the 12th century.

Riding equipment

Main articles: Saddle and StirrupTwo major innovations that revolutionized the effectiveness of mounted warriors in battle were the saddle and the stirrup.

Riders quickly learned to pad their horse's backs to protect themselves from the horse's spine and withers. Warriors fought on horseback for centuries with little more than a blanket or pad on the horse's back and a rudimentary bridle. To help distribute the rider's weight and protect the horse's back, some cultures created stuffed padding that resembles the panels of today's English saddle. Both the Scythians and Assyrians used pads with added felt attached with a surcingle or girth around the horse's barrel for increased security and comfort. Xenophon mentioned the use of a padded cloth on cavalry mounts as early as the fourth century BC.

The saddle with a solid framework, or "tree," provided a bearing surface to protect the horse from the weight of the rider, but was not widespread until the 2nd century AD. However, it made a critical difference, as horses could carry more weight when distributed across a solid saddle tree. A solid tree, the predecessor of today's Western saddle, also allowed a more built up seat to give the rider greater security in the saddle. The Romans are credited with the invention of the solid-treed saddle.

Arguably one of the most important inventions that made cavalry particularly effective was the stirrup. While a toe loop that held the big toe was used in India possibly as early as 500 B.C., and later a single stirrup was used as a mounting aid, the first set of paired stirrups appeared in China about 322 AD during the Jin Dynasty. By the 7th century, thanks primarily to invaders from Central Asia, stirrups spread across Asia to Europe. The stirrup, which allowed a rider greater leverage with weapons, as well as both increased stability and mobility while mounted, gave nomadic groups such as the Mongols a decisive military advantage. The knowledge of stirrups was known in Europe in the 8th century, but pictoral and literary references to their use date only from the 9th century. Widespread use appears to owe much to the Vikings, who spread the usage of the stirrup in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Tactics

The first archaeological evidence of horses used in warfare was between 4000 and 3000 BC in the steppes of Eurasia, in what today is Ukraine, Hungary and Romania. In those locations, not long after domestication of the horse, people began to live together in large fortified towns for protection from horseback-riding raiders. Prior to adoption of mounted warfare or a mounted lifestyle in general, horse nomads posed an extreme threat to the more sedentary cultures they encountered. Mounted raiders could attack and escape faster than villagers could follow. The use of horses in warfare was also documented in the earliest recorded history. One of the first depictions of equids is the "war panel" of the Standard of Ur, in Sumer, dated c. 2500 B.C., showing horses (or possibly onagers or mules) pulling a four-wheeled wagon.

Chariot warfare

See also: ChariotThe earliest documented examples of horses playing a role in combat were in chariot warfare. Among the first evidence of chariot use are the burials of the Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture in modern Russia and Kazakhstan, dated to approximately 2000 BC. The oldest evidence of what was probably chariot warfare in the Ancient Near East is the Old Hittite Anitta text, of the 18th century BC, which mentioned 40 teams of horses at the siege of Salatiwara. The Hittites became well known throughout the ancient world for their prowess with the chariot. Widespread use of the chariot in warfare across most of Eurasia coincides approximately with the development of the composite bow, known from c. 1600 BC. Further improvements in wheels and axles, as well as innovations in weaponry, soon resulted in chariots being driven in battle by Bronze Age societies from China to Egypt.

The Hyksos invaders brought the chariot to Ancient Egypt in the 16th century BC and the Egyptians adopted its use from that time forward. The oldest preserved text related to the handling of war horses in the ancient world is the Hittite manual of Kikkuli, which dates to about 1350 BC, and describes the conditioning of chariot horses.

Chariots were known in the Minoan civilization, inventoried on storage lists from Knossos in Crete, dating to around 1450 BC. Chariots were also used in China as far back as the Shang dynasty (ca. 1600-1050 BC), where they appear in burials. The high point of chariot use in China was in the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC), although they continued in use up until the 2nd century BC.

Descriptions of the tactical role of chariots in Ancient Greece and Rome are rare. The Iliad, possibly referring to Mycenean practices used circa 1250 BC, describes the use of chariots for transporting warriors to and from battle, rather than for actual fighting. Later, Julius Caesar, invading Britain in 55 and 54 BC, noted British charioteers throwing javelins, then leaving their chariots to fight on foot.

Cavalry

Main article: CavalrySome of the earliest examples of horses being ridden in warfare were archers or spear-throwers mounted on horseback, dating to the reigns of the Assyrian rulers Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III. However, these the riders sat far back on their horses, an awkward position for moving quickly, and the horses were usually held by a handler on the ground, keeping the archer free to use the bow. Thus these archers were more a type of mounted infantry than true cavalry. The Assyrians developed cavalry in response to invasions by nomadic people from the north, such as the Cimmerians, who entered Asia Minor in the 8th century, B.C. and took over parts of Urartu during the reign of Sargon II, approximately 721 B.C. Mounted warriors such as the Scythians also had an influence on the region in the 7th century BC. By the reign of Ashurbanipal in 669 B.C., the Assyrians had learned to sit forward on their horses in the classic position of riding still seen today and could be said to be true light cavalry. The ancient Greeks used both light horse scouts and heavy cavalry, although not extensively, possibly due to the cost of keeping horses.

Heavy cavalry was believed to have been developed by the Ancient Persians, although others argue for the Sarmatians. By the time of Darius (558-486 B.C.), Persian military tactics evolved to require horses and riders that were completely armoured, and a heavier, more muscled horse developed to carry the additional weight. Later, the ancient Greeks developed a heavy armoured cavalry, the most famous units being the companion cavalry of Alexander the Great. The Chinese of the 4th century BC during the Warring States (403 BC-221 BC) began to use cavalry against rival states, and in response to nomadic raiders from the north and west, the Chinese of the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD) developed effective mounted units. Cavalry was not used extensively during the Roman Republic period, but by the time of the Roman Empire, the Romans developed and made use of heavy cavalry,though backbone of the Roman army was the infantry.

The term cataphract describes some of the tactics, armour and weaponry of mounted units used from the time of the Persians up until the Middle Ages.

Asia

See also: History of the horse in South Asia and Mongol military tactics and organizationCentral Asia

Relations between the steppe nomads and the settled people in and around Central Asia were often marked by conflict. The nomadic lifestyle was well suited to warfare, and the steppe cavalry became some of the most militarily potent peoples in the world, only limited by their frequent lack of internal unity. Periodically, great leaders or changing conditions would organize several tribes into to one force, creating an almost unstoppable power. These unified groups included the Huns, who invaded Europe. At the time, no other major force could have conducted two campaigns with the same large army in both eastern France and northern Italy, over 500 miles apart, and much further on their actual route, within two successive campaign seasons, as the Huns under Attila did. Other unified nomadic forces included the Wu Hu attacks on China, and most notably, the Mongol conquest of much of Eurasia.

India

The literature of ancient India describes numerous Central Asian horse nomads. Some of the earliest references to use of horses in central Asian warfare are Puranic texts, which refer to an invasion of India by the joint cavalry forces of the Sakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas and Paradas, called the "five hordes" (pañca.ganah) or "Kśatriya" hordes (Kśatriya ganah). About 1600 BC, they captured the throne of Ayudhya by dethroning its Vedic king, Bahu. Later texts, such as the Mahabharata, written c. 950 BC, appear to recognize efforts taken to breed war horses and develop trained mounted warriors, stating that the horses of the Sindhu and Kamboja regions were of the finest quality, and that the Kambojas, Gandharas and Yavanas were considered expert in fighting from horse.

In technological innovation, an early form of the stirrup, a toe loop that held the big toe, is credited to the cultures of India, and may have been in use as early as 500 BC. Not long after, the cultures of Mesopotamia and Ancient Greece clashed with those of central Asia and India. Herodotus (484 BC-425 BC) wrote that the Gandarian mercenaries of Achaemenids from the twentieth strapy were recruited in the army of emperor Xerxes I (486-465 BC), which he led against the Greeks. A century later, the Men of the Mountain Land from north of Kabol-River (possibly the Kamboja cavalry, from south of the Hindu kush near medieval Kohistan), served in the army of Darius III when he fought against Alexander the Great at Arbela in October, 331 BC. In battle against Alexander at Massaga in 326 BC, the Assakenoi forces included 20,000 cavalry. Later, the cavalry forces of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Kiratas, Parasikas and Bahlikas helped Chandragupta Maurya (c. 320 BC-c. 298 BC) defeat the ruler of Magadha and placed Chandragupta on the throne, thus laying the foundations of Mauryan Dynasty in Northern India.

Later, Mughal armies used gunpowder weapons, but were slow to replace the composite bow of the traditional cavalryman. Under the impact of European military successes in India, some Indian rulers adopted the newer European system of massed cavalry charges, although others did not. By the eighteenth century, Indian armies continued to field cavalry, but mainly of the heavy variety.

China and Japan

The Chinese used chariots for horse-based warfare until light cavalry forces became common during the Warring States era (402 BC-221BC). A major proponent of the change to riding horses instead of chariots was Wu Ling, who lived circa 320 BC. However, the conservative forces in China always fought against change, and cavalry never became as dominant as in Europe. Cavalry in China also did not benefit from the additional cachet attached to being the military branch dominated by the nobility.

The Japanese switched from an emphasis on mounted bowmen to mounted spearmen during the Sengoku Period (1467-1615 AD). The samurai, or noble and warrior class, of Japan continued to be cavalry, as they had been for centuries.

Islamic world

Muslim warriors conquered North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula during the 7th and 8th centuries A.D. Following the Hegira or Hijra of Muhammad in 622 AD, Islam spread across the known world of the time. By 630 AD, Muslim influence expanded across the Middle East and into North Africa. By 711 AD, the light cavalry of Muslim warriors had reached Spain, and controlled most of the Iberian peninsula by 720. Their mounts were of various oriental types, including the Barb from North Africa. A few Arabian horses may have come with Syrian horsemen who settled in the Guadalquivir valley. Another strain of horse that came with Islamic invaders was the Turkoman.

Muslim invaders traveled north from Spain into France, where they were stopped by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732 AD. Although this battle is often cited as the reason that the Franks turned to heavy cavalry, because of a need to fight the light cavalry of the Muslims, the Franks were also facing mounted enemies in the Lombards and Frisians. The need to carry more armour led to the Franks breeding for heavier, bigger horses. Over time, this type of breeding gave rise to the powerful but agile medieval war horse known as the destrier.

Europe and the Americas

European knights

Main article: Horses in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages in Europe, there were three primary types of horses used in warfare: The destrier, the courser, and the rouncey. The rouncey was the everyday horse of a squire or for the mounted man-at-arms, suitable for both general riding and war. The courser was a fast horse, well-suited to carrying messages between armies, while the more-famous, highly-trained destrier was reserved for the richest knights and nobility. In later periods the growth in importance of tournaments led to the breeding of specialized destriers that were only used in tournaments. A generic word often used to describe medieval war horses is charger, which appears interchangeable with the other terms.

The destrier of the early Middle Ages was a moderately larger horse than the courser or rouncey, in part to accommodate heavier armoured knights. For example, the horse ridden by King William I of England in the Battle of Hastings in 1066 was said to be an Iberian-type animal brought from Spain by William Giffard. It was probably about a bit taller than the average size of horses ridden by William's knights, which were probably about 14.2 hands (58 inches (1.5 m)) tall to about 15 hands (60 inches (1.5 m)) tall. As the amount of armour and equipment increased in the later Middle Ages, the size of the horses increased as well; some late medieval horse skeletons were of horses 15 hands and taller.

Despite the popular image of a European knight on horseback charging into battle, pitched battles were avoided, if at all possible, with most offensive warfare in the early Middle Ages taking the form of sieges, or swift mounted raids called chevauchées, with the warriors lightly armed on swift horses.

As time passed, the mounted knight was seen less on the battlefield and more often as a competitor in tournaments: war-game events with stylized pageantry. Larger horses, some possibly as tall as 17 hands (68 inches (1.7 m)) and 1,500 pounds (680 kg), with the strength to carry both a knight and stylized plate armour were developed. In addition to height and weight, this type of horse was selected for agility and trainability. It is a matter of scholarly debate how important the tournament was to training for actual warfare in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries. Some historians suggest that the tournament had become a theatrical event by the fiftheenth and sixteenth centuries. Others argue that jousting continued to help cavalry train for battle until the Thirty-Years War. The expense of keeping, training and outfitting these specialized horses prevented the majority of the population from owning them.

Stallions, or uncastrated male horses, were often used as war horses in Europe due to their natural aggression. A thirteenth century work describes destriers "biting and kicking" on the battlefield. However, the use of mares, or female horses, by European warriors cannot be discounted from literary references, and mares were the preferred war horse of the Moors, the Islamic invaders who attacked various European nations from 700 AD through the 15th century.

Experts dispute the precise reason for the demise of the armoured knight. Some claim the invention of gunpowder and the musket rendered the knight obsolete, while others date it earlier, to the use of the English longbow, which was introduced into England from Wales in 1250 and used with decisive force in conflicts such as the Battle of Crécy in 1346. Some give the decline of cavalry as effect of both technologies. However, other authorities suggest that such new technologies contributed to the development of knights, rather than to their decline. For example, plate armour was first developed to resist the crossbow bolts of the early medieval period, and the rise of the English longbow during the Hundred Years' War further increased the use and sophistication of plate armour, culminating in the full harness worn by the early 15th century. Furthermore, from the 14th century on, most plate was made from hardened steel, which could resist early musket ammunition. Yet, this stronger design did not render the plate increasingly impracticable; a full harness of musket-proof plate from the 17th century weighed 70 pounds (32 kg), significantly less than 16th century tournament armour.

It is most likely that the decline of the knight was brought about by changing structures of armies and various economic factors and not simply an obsolescence caused by new technology. By the sixteenth century, the concept of a combined-arms professional army first developed by the Swiss had spread throughout Europe, and was accompanied by improved infantry tactics. These professional armies placed an emphasis on training and paid contracts, rather than the ransom and pillaging which reimbursed knights in the past. This situation, when coupled with the rising costs involved in outfitting and maintaining knights’ armour and horses, probably led many members of the traditional knightly classes to abandon their profession.

It is also hard to trace what happened to the bloodlines of destriers, as the type seems to disappear from record during the seventeenth century, at least in England. The great horse was both smaller and more agile than the modern draft horse, with breeds such as the Andalusian, and Friesian claiming to be the direct descendants of destriers. However, draft horse breeds such as the Belgian and Shire horse also claim descent from the horses developed to carry full armour.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period

With the development of muskets and other light firearms in Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, light cavalry again became useful for both battles and field communication, using fast, agile horses to move quickly across battlefields. Thus, the heavy armoured horse of the medieval knight no longer had use in combat. Although the former knightly class attempted to preserve their mounted battlefield role by developing ever more complex maneuvers and incorporating the use of firearms while on horseback, firearms-armed infantry, especially where combined with pikemen, were able to counter cavalry with relative ease throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Thus, European cavalry moved from a central, "shock combat" role to a flanking role, used mainly to harry and to disrupt artillery from being deployed freely.

The Americas

Horses were particularly useful in the 16th century as a weapon of war for the Conquistadors: when these Spanish warriors came to the Americas and conquered the Aztec and Inca empires, horses and gunpowder provided a crucial edge. Because the horse had been extinct in the Western Hemisphere for approximately 10,000 years, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas had no warfare technologies that could overcome the considerable advantage provided by European horses and weapons. However, the American Indian people quickly learned to use horses, and the tribes of the Great Plains, such as the Comanche and the Cheyenne, became renowned horseback fighters, again demonstrating the efficiency of light cavalry, eventually becoming a considerable problem for the United States Army.

20th century

Light cavalry was still seen on the battlefield at the beginning of the 20th century. Though formal mounted cavalry began to be phased out as fighting forces during or immediately after World War I, cavalry units that included horses still had military uses well into World War II.

World War I

Prior to World War I, cavalry was used as a way of flanking the sides of the opposing army and exploiting breaches in the enemy's line. In the initial stages, of the war, cavalry skirmishes were common, and horse-mounted troops were widely used for reconnaissance. However, cavalry on the Western Front were used mainly as a flanking force during the "Race to the Sea" in 1914, but were of little use once trench warfare was established. Cavalry played a greater role on the more fluid fronts of Eastern Europe's World War I battlefields, where trench warfare was less common than at the Western Front. Yet even in the east, trench lines eventually appeared along many fronts, reducing the ability of cavalry to play a decisive role or freely use their mobility.

On both fronts, the horse was used primarily as a pack animal. Due to the fact that railway lines could not withstand artillery bombardments shelling the areas directly to the rear of entrenched battle lines, horses carried ammunition and supplies between the railheads and the rear trenches, though the horses generally were not used in the actual trench zone. This role of horses was critical, and thus horse fodder was the single largest commodity Britain shipped to its Army in France during the war, even above ammunition and shells.

World War II

One of the most famous examples of actual horse-mounted units in World War II was found in the the underequipped Polish army, which used its horse cavalry in World War II to defend Poland against the armies of Nazi Germany during the 1939 invasion. While there is a popular belief that the Polish cavalry engaged in futile charges against tank units, this is a misconception. Two examples illustrate how the myth developed. First, because motorized vehicles were in short supply, the Poles used horses to pull anti-tank weapons into position. Second, there were a few incidents when Polish cavalry was trapped by German tanks, and attempted to fight free. However, this did not mean that the Polish army chose to attack tanks with horse cavalry. Later, on the Eastern Front, the Red Army did deploy cavalry units effectively against the Germans.

Other nations used horses extensively during World War II, though not in direct combat. The German and the Soviet armies used horses until the end of the war for the transportation of troops and supplies. The German Army, strapped for motorized transport because its factories were needed to produce tanks and aircraft, used around 2.75 million horses - more than it had used in World War I. The Soviets used 3.5 million horses. In both cases, most horses died in the course of military service.

The British Army used horses in warfare during the beginning of the war, with the final British cavalry charge occurring on March 21, 1942. Horses and mules were an essential form of transport, especially in rough terrain such as was found in Italy and the Middle East. While the United States Army utilized a few cavalry and supply units during the war, there were concerns that in rough terrain, horses were not used often enough. In the campaigns in North Africa, generals such as George S. Patton lamented their lack, saying, "had we possessed an American cavalry division with pack artillery in Tunisia and in Sicily, not a German would have escaped."

In the military today

Today, formal combat units of mounted cavalry are mostly a thing of the past, with horseback units within the modern military used for reconnaissance, ceremonial, or crowd control purposes. With the rise of the mechanized technology, horses in formal national militias were displaced by modern tank warfare, which is sometimes still referred to as "cavalry." Organized armed fighters on horseback are occasionally seen, particularly in the third world, though they usually are not officially recognized as part of any national army. The best-known current examples are the Janjaweed, militia groups seen in the Darfur region of Sudan, who became notorious for their attacks upon unarmed civilian populations in the Darfur conflict.

Reconnaissance and patrol

Although horses have little combat use today by modern armies, the military of many nations still maintain small numbers of mounted units for certain types of patrol and reconnaissance duties in extremely rugged terrain, including the current conflict in Afghanistan. The only remaining operationally-ready, fully horse-mounted regular regiment in the world is India's 61st Cavalry.

Ceremonial and educational uses

Many countries throughout the world maintain traditionally-trained and historically uniformed cavalry units for ceremonial, exhibition, demonstration or educational purposes. One example is the Horse Cavalry Detachment of the U.S. Army's 1st Cavalry Division. This unit, made up of active duty soldiers, still functions as an active unit, trained to approximate the weapons, tools, equipment and techniques used by the United States Cavalry in the 1880s. The horse detachment is headquartered at Fort Hood, Texas and is charged with public relations, change of command ceremonies and public appearances. A similar detachment is the Governor General's Horse Guards, Canada's Household Cavalry regiment and the last remaining mounted cavalry unit in the Canadian Forces. Nepal's King's Household Cavalry is a ceremonial unit with over 100 horses and is the remainder of the Nepalese cavalry that existed since the 19th century.

Related modern uses

Today, many of the historical military uses of the horse have evolved into peacetime applications, including exhibitions, historic reenactment, work of peace officers, everyday riding and competitive events.

Historical reenactment

Main article: Historical reenactmentHorses are used in many historical warfare reenactments, including everything from the Battle of Hastings to the recreation of 20th century battles. Reenactors try to recreate the conditions of the battle or tournament in as much detail as possible, with equipment that is as authentic as possible, although this is sometimes difficult due to changes in technology and the fact that much of the equipment of past eras is no longer manufactured.

Law enforcement and public safety

Main articles: Mounted police and Mounted search and rescue

Mounted police have been used since the 18th century, with the first recorded instance being in 1758 with the creation of the London Bow Street Horse Patrol. Since then, mounted police units have been used worldwide to control traffic and crowds, patrol public parks, keep order in processionals and during ceremonies and perform general street patrol duties. Today, many cities, including London, Barcelona and New York City still have mounted police units. In rural areas, horses are used by mounted police forces for patrols over rugged terrain, crowd control at religious shrines and border patrol.

In rural areas, law enforcement that operates outside of incorporated cities may also have mounted units. These include specially deputized, paid or volunteer mounted search and rescue units sent into roadless areas on horseback to locate missing people. Law enforcement in national parks, national forests, wilderness areas, and other types of wildlife refuge may use horses in areas where mechanized transport is difficult or prohibited. Horses can be an essential part of an overall team effort as they can move faster on the ground than a human on foot, can transport heavy equipment, and provide a more rested rescue worker when a subject is found. The U.S. Border patrol notes that they can stable 10 horses for the same cost as maintaining one off-road 4x4 truck.

Equestrian competition

Main articles: Equestrian at the Summer Olympics, Dressage, Show jumping, and EventingWhen the first equestrian events were held at the Olympics in 1912, competition was restricted solely to serving officers on military horses. The games remained dominated by military riders through the 1948 Games. In 1952, as cavalry divisions were replaced by mechanization, military riders were in the minority and civilian riders were allowed to compete. The three modern-day Olympic equestrian events of eventing, show jumping, and dressage all have their roots in cavalry skills and classical horsemanship.

Dressage traces its origins to the works of Xenophon and his works on cavalry training methods, most notably On Horsemanship, but became recognized in its modern form during the Renaissance when training methods of classical dressage developed in response to a need for more intelligent management of horses in battle where firearms were used. The Spanish Riding School of Vienna, Austria was created to train horses with the classical philosophy of Xenophon and continues this tradition today.

Eventing developed out of cavalry officers' needs for versatile, well-schooled horses. The discipline included a dressage phase, to test the ability of the cavalry mount on the parade ground, the endurance phase, to test the mount's fitness and ability to carry messages across the countryside, traveling quickly over rough terrain, and the stadium jumping phase, as a test to ensure that the mount was still fit enough to continue after the rigors of the endurance competition. It evolved into the modern three-phase competition seen today.

Show jumping developed from fox hunting in England during the mid-19th century, and at the beginning used natural objects in the countryside such as walls, ditches and fences. British cavalry officers were the first to take up the sport, as they considered jumping to be good training for their horses, and other European cavalries soon following the British lead. Leaders in the development of modern riding technique over fences, such as Fredrico Caprilli, came from military ranks.

Sword, lance and revolver competitions are also held, especially in Britain, to test the combat skills of mounted horsemen. Tent pegging, which tests the use of lance at speed, is usually part of these competitions. Points are awarded for skill, efficiency and style in many competitions, although in some cases the winner is simply the individual who hits the greatest number of targets.

See also

Notes

- Bennett, Conquerors p. 31

- Benjamin, Garfield. "History of Medieval Armor - Protection Was Everything". medieval-castle-siege-weapons.com. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- Ainslie Complete Guide pp. 227-228

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 19

- Nicolle Crusader Knight p. 14

- American Endurance Ride Conference (Nov. 2003). "Chapter 3, Section IV: Size". Endurance Rider's Handbook. AERC. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Baker, A Treatise on Roads and Pavements, pp. 22-23

- Luthy, Dusty. "Mighty horses pull more than their weight at fair". The Lebanon Daily Record. Horsepull Results. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- Chamberlin Horse pp. 106-110

- Eastern Draft Horse Association. "History of the draft horse dynamometer machine". History. Eastern Draft horse Association. Retrieved 2008-07-17.Note: Traction force of horses pulling a load, as measured by a dynamometer, can be between 50 and 300 kgf, depending on speed and distance.

- Eastern Draft Horse Association. "Eastern Draft Horse Association Rules". History. Eastern Draft horse Association. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Horsepull.com. "Reords". Horsepull.com. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 9-11

- Chamberlin Horse p. 146

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 10-11

- Bennett, Conquerors, p. 71

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 9, 13-14, 22

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 13-14

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 16

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 2, 9

- ^ Bennett, Conquerers, p. 29

- Oakeshott, A Knight and His Horse, pp. 11-15

- ^ Edwards, The Arabian, p. 11, 13

- Hyland, The Medieval Warhorse, pp. 85-86

- Gravett, English Medieval Knight 1300-1400, p. 59

- Bennett, Conquerors, pp. 54, 137

- The Royal Armouries used a 15.2 hand Lithuanian Heavy Draught mare as a model for statues displaying various fifteenth-sixteenth century horse armours, as her body shape was an excellent fit. see Hyland, The Warhorse, p. 10

- ^ United States Dressage Federation. "History of Dressage". USDF Website. United States Dressage Federation. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Clark "Introduction" Medieval Horse pp. 22-27

- Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages, p. 30

- Gies, et.al., Daily Life in Medieval Times, p. 88

- For example see: Clark, "Introduction" The Medieval Horse and its Equipment, p. 23; Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages, p. 30

- Fort, Eating Up Italy, p. 171

- ^ Hubbell, "21st century Horse Soldiers", Western Horseman, pp. 45-50

- Equine Research Equine Genetics p. 190

- Ensminger Horses and Horsemanship pp. 85-87

- ^ Chamberlin Horse pp. 48-49

- ^ Hope, The Horseman's Manual, ch. 1 and 2.

- ^ Hyland Medieval Warhorse pp. 115-117

- Chamberlin Horse pp. 197-198

- Equestrian Federation of Australia. "Dressage Explained". EFA Website. Equestrian Federation of Australia. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- Hyland Equus pp. 214-218

- ^ Gravett Tudor Knight pp. 29-30

- Amschler, "The Oldest Pedigree Chart", The Journal of Heredity, pp. 233-238

- ^ Trench, A History of Horsemanship, p. 16

- ^ Anthony, David W. and Dorcas R. Brown. "The Earliest Horseback Riding and its Relation to Chariotry and Warfare". Harnessing Horsepower. Institute for Ancient Equestrian Studies. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Pritchard, The Ancient Near East, Illustration 97

- Chamberlin Horse pp. 102-108

- Needham, Science and Civilization in China, p. 322

- Chamberlin Horse pp. 109-110

- Needham, Science and Civilization in China, p. 317

- Bennett and others Fighting Techniques p. 70 & p. 84

- Bennett, Conquerers, p. 43

- ^ Ellis Cavalry p. 14

- ^ Newby, Jonica, Jared Diamond and David Anthony (1999-11-13). "The Horse in History". The Science Show. Radio National. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chamberlin Horse pp. 110-114

- China Daily. "The invention and influences of stirrup". The Development of Chinese Military Affairs. Chinese Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 51-53

- Bennet Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare p. 300

- Nicolle Medieval Warfare Soucebook: Warfare in Western Christendom pp. 88-89

- ^ Keegan, A History of Warfare, p. 188

- Bennett, Conquerers, p. 23

- Crouwel, et.al., "The Origin of the True Chariot", Antiquity, pp. 934-939

- Drower "Syria" Cambridge Ancient History pp. 493-495

- Hitti, Lebanon in History , pp. 77-78.

- Drower "Syria" Cambridge Ancient History pp. 452, 458

- Kupper "Egypt" Cambridge Ancient History p. 52

- Drower "Syria" Cambridge Ancient History p. 493

- ^ Adkins Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece pp. 94-95

- Willetts "Minoans" Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations p. 209

- Bennett Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare p. 67

- Johnston, Ian (translator). "Homer's The Iliad". Johnstonia. Vancouver Island University. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Caius Julius Caesar. ""De Bello Gallico" and Other Commentaries, Chapter 33". Project Gutenberg EBook. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Warry Warfare in the Classical World pp. 220-221

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 13

- Perevalov "Sarmatian Lance" Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia pp. 7-21

- Chamberlin Horse pp. 154-158

- Ebrey, Pre-Modern East Asia, pp. 29-30.

- Goodrich Short History p. 32

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 30-35

- Adkins Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome pp. 51-55

- Whitby Rome at War pp. 19-21

- Bennett, et al. Fighting Techniques pp. 76-81

- Nicolle Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbors p. 185

- Ellis Cavalry p. 120

- Nicolle Attila pp. 6-10

- All Empires. "Introduction: The Restless Horsemen". Steppe Nomads and Central Asia. All Empires. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Nicolle Attila pp. 20-23

- Goodrich Short History p. 83

- Nicolle Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbors pp. 91-94

- Partiger, Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, pp. 147-148, 182-183

- Sarma, Vishnudharmotri Purana, Chapter 118:Military Wisdom in the Puranas, p. 64; See also: Sinha, Post-Gupta Polity (A.D. 500-750), p. 136

- Hopkins, "The Social and Military Position of the Ruling Caste in Ancient India",Journal of the American Oriental Society , p. 257; Bongard-Levin, Ancient Indian Civilization, p. 120

- Herodotus, IV.65-66.

- Olmstead, History of Persian Empire, p 232; Raychaudhuri, Political History of Ancient India, p 216.

- Sastri, Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, p. 49

- Mudra-Rakshasa II.

- Gordon "Limited Adoption" Indian Economic and Social History Review pp. 230-232

- Gordon "Limited Adoption" Indian Economic and Social History Review p. 241

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 19-20

- Turnbull War in Japan pp. 15-20

- Bennett, Conquerers,' pp. 97-98

- ^ Hyland Medieval Warhorse pp. 55-57

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 47-50

- Oakeshott, A Knight and his Horse p. 12

- Contamine War in the Middle Ages pp. 67-73

- Labarge Mistress, Maids, and Men pp. 158-160

- International Museum of the Horse. "Horses Were Specifically Bred for Warfare and Chivalry". Legacy of the Horse: Medieval Horse: 476 - c. 1450. International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Nicolle Medieval Warfare Sourcebook: Warfare in Western Christendom pp. 124-125, 169

- Hyland Medieval Warhorse p. 88

- Prestwich Armies and Warfare p. 347

- ^ France Western Warfare pp. 23-25

- Hyland Medieval Warhorse pp. 85-86

- Bennet, et.al., Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World, p. 121

- Chevauchées were the preferred form of warfare for the English during the Hundred Years' War (see, amongst many, Barber, The Reign of Chivalry, pp. 34-38) and the Scots in the Wars of Independence (see Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages)

- Barber, The Reign of Chivalry, p. 42

- International Museum of the Horse. "Shire Draft Horse". Horse Breeds of the World. International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Watanabe-O'Kelly "Tournaments" European History Quarterly pp. 451-463

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 43, 49-50

- ^ Bumke, Courtly Culture, pp. 175-178

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 22

- Hale War and Society pp. 54-56

- Springfield Armory Museum. "Musket". Springfield Armory Museum - Collection Record. Springfield Armory Museum. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 65-67

- Bennett and others Medieval Fighting Techniques pp. 123-124

- ^ Williams, Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour, chapter "The Metallurgy of Medieval Arms and Armour", pp. 51-54

- ^ Carey, Warfare in the Medieval World, pp. 149-50, 200-02

- Oakeshott, A Knight and his Horse, p. 104

- Robards, The Medieval Knight at War, p 152

- Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages p. 30

- Clark "Introduction" Medieval Horse pp. 23-27

- International Museum of the Horse. "Andalusian". Horse Breeds of the World. International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- International Museum of the Horse. "Friesian Horse". Horse Breeds of the World. International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Oklahoma State University. "Shire". Breeds of Livestock - Horses. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Oklahoma State University. "Belgian". Breeds of Livestock - Horses. Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 98-103

- Keegan, A History of Warfare, p. 341

- Keegan, A History of Warfare, p. 344

- Bennett, Conquerers, p. 195, 237

- Bennett, Conquerers, p. 207

- Ellis Cavalry pp. 156-163

- ^ Waller, Anna L. (1958). "Horses and Mules and National Defense". Office of the Quartermaster General. Army Quartermaster Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Willmott, First World War, p. 46

- Willmott, First World War, p. 60

- ^ Willmott, First World War, p. 99

- ^ Keegan, A History of Warfare, p. 308

- Time Staff, "The New Pictures", Time

- Davies God's Playground Volume II pp. 324-325

- Davies God's Playground Volume II p. 325

- Tucker, Encyclopedia of World War II, p. 309

- Army Medical Services Museum. "History of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps". RAVC History. Army Medical Services Museum. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Bielakowski, "General Hawkins's War", The Journal of Military History, p. 137

- Lacey, "In Sudan, Militiamen on Horses Uproot a Million", New York Times

- Pelton, "Afghan War Eyewitness on Warlords, Future, More", National Geographic News

- Deccan Herald. "61st India's 61st Cavalry rides into 56th year". National News. The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- First Cavalry Division. "Horse Cavalry Detachment". FCD Website. First Cavalry Division. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Canadian Department of National Defense. "Governor General's Horse Guards". Canadian National Defense Website. Canadian Department of National Defense. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- Canadian Department of National Defense (1999-01-04). "The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces" (PDF). The Saskatchewan Dragoons Website. Canadian Department of National Defense. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- Haviland, "Nepalese cavalry to be relocated", BBC News

- "1066 Battle Re-enactment: The Big Match - King Harold V William of Normandy at the Battle of Hastings". 1066country.com. Hastings Borough Council. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- Australian Light Horse Associaition. "Australian Light Horse Association Homepage". ALHA Website. Australian Light Horse Association. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Handler, "Dyssimulation", Cultural Anthropology, pp. 243-244

- Edwards, The Encyclopedia of the Horse, p. 308

- For example: Northwest Horseback Search and Rescue. "Northwest Horseback Search and Rescue". NHSR Website. Northwest Horseback Search and Rescue. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Northwest Horseback Search and Rescue. "Why Search on Horseback?". NHSR Website. Northwest Horseback Search and Rescue. Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- Kane, "The horse patrol-running neck and neck with technology", Custom and Border Protection Today

- Edwards, The Complete Horse Book, p. 292

- Edwards, The Complete Horse Book, p. 296

- Reuters (Aug. 7, 2008). "Factbox for Equestrianism". Reuters Website. Reuters. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Bryant, Olympic Equestrian, pp. 14-15

- Brownlow, Mark. "History of the Spanish Riding School". Visiting Vienna. Mark Brownlow. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- Spanish Riding School. "The Renaissance of Classical Equitation". Der Spanischen Hofreitschule Wien (in English). Spanish Riding School. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- Price, The American Quarter Horse, p. 238

- CBC Sports. "Gold, silver, bronze? Not in 1932". Olympic Games. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- International Museum of the Horse. "The Horse in 19th century American Sport". The Legacy of the Horse. International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- Edwards, The Complete Horse Book, pp. 326-327

References

- Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (1998). Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512491-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Adkins, Roy; Adkins, Lesley (1998). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512332-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ainslie, Tom (1988). Ainslie's Complete Guide to Thoroughbred Racing (Third Edition ed.). New York: Fireside. ISBN 0-671-65655-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Amschler, Wolfgang (June 1935). "The Oldest Pedigree Chart". The Journal of Heredity. Volume 26, Number 6.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Baker, Ira Osborn (1918). A Treatise on Roads and Pavements. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Barber, Richard (2005). The Reign of Chivalry (2nd Edition ed.). Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1843831821.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Bennett, Deb (1998). Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship (1st Edition ed.). Solvang, CA: Amigo Publications Inc. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Bennett, Matthew (2001). Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2610-X.

- Bennett, Matthew; Bradbury, Jim; DeVries, Kelly; Dickie, Iain; Phyllis Jestice (2005). Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World : Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0-312-34820-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bielakowski, Andrew M. (Jan. 2007). "General Hawkins's war: The Future of the Horse in the U.S. Cavalry". The Journal of Military History. Volume 71, Number 1.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Bongard-Levin, G.M. (1985). Ancient Indian Civilization. Humanities Press Intl Inc.

- Bryant, Jennifer O. (2000). Olympic Equestrian: The Sports and the Stories from Stockholm to Sydney (1st Edition ed.). Canada: The Blood-Horse, Inc. ISBN 1-58150-044-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Bumke, Joachim, translated by Thomas Dunlap (2000). Courtly Culture: Literature and Society in the High Middle Ages. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 1585670510.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Carey, Brian Todd, Allfree, Joshua B and Cairns, John (2006). Warfare in the Medieval World. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1844153398.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chamberlin, J. Edward (2006). Horse: How the Horse Has Shaped Civilizations. Bluebridge. ISBN 0-9742405-9-1.

- Clark, John (2004). "Introduction: Horses and Horsemen in Medieval London". The Medieval Horse and its Equipment: c.1150-c.1450 (Rev. 2nd Edition ed.). Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-844383-097-3.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Contamine, Philippe (1984). War in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13142-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Crouwel, J.H. and M.A. Littauer (Dec. 1996). "The Origin of the True Chariot". Antiquity. Volume 70, Number 270.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground: A History of Poland: Volume II 1795 to the Present (Revised Edition ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925340-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Davis, R.H.C. (1989). The Medieval Warhorse. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500251029.

- Devereux, Frederick L (1979). The Cavalry Manual of Horse Management (Reprint of 1941 edition ed.). Cranbury, NJ: A. S. Barnes. ISBN 0-498-02371-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Drower, Margaret S. (1973). "Syria c. 1550-1400 BC". The Cambridge Ancient History: The Middle East and the Aegean Region c. 1800-1380 BC Volume II Part I (Third Edition ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. pp. 417-525. ISBN 0-521-29823-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help) - Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, and James B. Palais (2005). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0618133860.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Edwards, Elwyn Hartley and Candida Geddes (editors) (1987). The Complete Horse Book. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square, Inc. ISBN 0943955009.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Edwards, Elwyn Hartley (1994). The Encyclopedia of the Horse (1st American Edition ed.). New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 1564586146.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Edwards, Gladys Brown (1973). The Arabian: War Horse to Show Horse (Revised Collectors Edition ed.). Arabian Horse Association of Southern California, Rich Publishing.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Ellis, John (2004). Cavalry: The History of Mounted Warfare. Pen & Sword Military Classics. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-096-8.

- Ensminger, M. E. (1990). Horses and Horsemanship: Animal Agriculture Series (Sixth Edition ed.). Danville, IL: Interstate Publishers. ISBN 0-8134-2883-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Equine Research, Inc. (1978). Equine Genetics & Selection Procedures. Grand Prairie, TX: Equine Research.

- Fort, Matthew (2005). Eating Up Italy: Voyages on a Vespa. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0007190980.

- France, John (1999). Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000-1300. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8607-6.

- Gies, Frances and Gies, Joseph (2005). Daily Life in Medieval Times (2nd Edition ed.). Hoo, UK: Grange Books. ISBN 1840138114.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Goodrich, L. Carrington (1959). A Short History of the Chinese People (Third ed.). New York: Harper Torchbooks. OCLC 3388796.

- Gordon, Stewart (1998). "The Limited Adoption of European-style Military Forces by Eighteenth Century Rulers in India". Indian Economic Social History Review. 35 (35): 229–245. doi:10.1177/001946469803500301.

- Gravett, Christopher (2002). English Medieval Knight 1300-1400. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-145-1.

- Gravett, Christopher (2006). Tudor Knight. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-970-3.

- Hale, J. R. (1986). War and society in Renaissance Europe, 1450-1620. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3196-2.

- Handler, Richard and William Saxton (August 1988). "Dyssimulation: Reflexivity, Narrative and the Quest for Authenticity in "Living History"". Cultural Anthropology. Volume 3, Number 3.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Haviland, Charles (June 8, 2008). "Nepalese cavalry to be relocated". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-08-07.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Hitti, Phillip K. (1957). Lebanon in History. London: MacMillan and Co. OCLC 185202493.

- Hope, Lt. Col. C.E.G (1972). The Horseman's Manual. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0684136228.

- Hopkins, Edward W. (1889). "The Social and Military Position of the Ruling Caste in Ancient India, as Represented by the Sanskrit Epic". Journal of American Oriental Society. Volume 13.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hubbell, Gary (Dec. 2006). "21st century Horse Soldiers". Western Horseman.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Hyland, Ann (1990). Equus: The Horse in the Roman world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04770-3.

- Hyland, Ann (1994). The Medieval Warhorse: From Byzantium to the Crusades. London: Grange Books. ISBN 1-85627-990-1.

- Hyland, Ann (1998). The Warhorse 1250-1600. UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-0746-0.

- Kane, Linda (Oct/Nov 2003). "The horse patrol-running neck and neck with technology". Custom and Border Protection Today. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Keegan, John (1994). A History of Warfare (1st Edition ed.). Vintage Books. ISBN 0679730826.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Kupper, J. R. (1973). "Egypt: From the Death of Ammenemes III to Seqenenre II". The Cambridge Ancient History: The Middle East and the Aegean Region c. 1800-1380 BC Volume II Part I (Third Edition ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. pp. 42-76. ISBN 0-521-29823-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help) - LaBarge, Margaret Wade (2004). Mistress, Maids and Men: Baronial Life in the Thirteenth Century. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-499-4.

- Lacey, Marc (May 4, 2004). "In Sudan, Militiamen on Horses Uproot a Million". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Nicolle, David (1990). Attila and the Nomad Hordes: Warfare on the Eurasian steppes 4th-12th centuries. London: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-996-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Nicolle, David (2002). Companion to Medieval Arms and Armour. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 0851158722.

- Nicolle, David (1996). Crusader Knight. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-934-4.

- Nicolle, David (1998). Medieval Warfare Source Book: Christian Europe and its Neighbors. Leicester: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-861-9.

- Nicolle, David (1999). Medieval Warfare Source Book: Warfare In Western Christendom. Dubai: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-889-9.

- Oakeshott, Ewart (1998). A Knight and His Horse. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions. ISBN 0-8023-1297-7.

- Olmstead, A.T. (1959). History of Persian Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226627772.

- Partiger, F.E. (1997). Ancient Indian Historical Tradition (Reprint Edition ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Pelton, Robert Young (Feb. 15, 2002). "Afghan War Eyewitness on Warlords, Future, More". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Perevalov, S. M. (translated M. E. Sharpe) (2002). "The Sarmatian Lance and the Sarmatian Horse-Riding Posture". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 41 (4): 7–21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Prestwich, Michael (1996). Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07663-0.

- Price, Steven D. and Don Burt (1998). The American Quarter Horse: An Introduction to Selection, Care, and Enjoyment. Globe Pequot. ISBN 155821643X.

- Pritchard, James B (1958). The Ancient Near East. Vol. Volume 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 382004.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1996). Political History of Ancient India. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195643763.

- Robards, Brooks (1997). The Medieval Knight at War. London: Tiger Books. ISBN 1855019191.

- Sarma, Prof Sen (1969). Vishnudharmotri Purana, Kh. II,.

- Sastri, Dr K. A. Nilakanta (1967). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas. Orient Book Distributors. ISBN 0896841677.

- Sinha, Ganesh Prasad (1972). Post-Gupta Polity (A.D. 500-750): A Study of the Growth of Feudal Elements and Rural Administration. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak. OCLC 695415.

- Time Staff (April 22, 1940). "The New Pictures". Time. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Trench, Charles Chenevix (1970). A History of Horsemanship. London: Doubleday and Company. ISBN 0385031092.

- Tucker, Spencer and Priscilla Mary Roberts (2004). Encyclopedia of World War II: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576079996.

- Turnbull, Stephen R. (2002). War in Japan 1467-1615. Essential Histories. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-480-9.

- Warry, John Gibson (2000). Warfare in the Classical World. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 076071696x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (1990). "Tournaments and their Relevance for Warfare in the Early Modern Period". European History Quarterly. 20 (20): 451–463. doi:10.1177/026569149002000401.

- Willetts, R. F. (1980). "The Minoans". In Arthur Cotterell (ed.). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-011434-3.

- Willmott, H.P. (2003). First World War. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 1405300299.

- Whitby, Michael (2002). Rome at War 229-696 AD. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-359-4.

Further reading

- Hacker, Barton C. (1997). "Military Technology and World History: A Reconnaissance" (fee required). The History Teacher. 30 (4): 461–487. doi:10.2307/494141. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- The British Cavalry Regiments of 1914-1918

- The Society of the Military Horse

- The Institute for Ancient Equestrian Studies (IAES)