| Revision as of 06:38, 30 May 2016 editDcirovic (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers253,275 editsm →Superionic conductors: clean up using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:37, 19 January 2025 edit undoMinusBot (talk | contribs)Bots3,739 editsm →Other Inorganic materials: Proper minus signs and other cleanup. Report bugs, errors, and suggestions at User talk:MinusBotTag: AWB | ||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 31 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ], specifically, ], in a static ].]] | |||

| In ], '''fast ion conductors''' are |

In ], '''fast ion conductors''' are ] ] with highly mobile ]s. These materials are important in the area of ], and are also known as '''solid electrolytes''' and '''superionic conductors'''. These materials are useful in batteries and various sensors. Fast ion conductors are used primarily in ]s. As solid electrolytes they allow the movement of ions without the need for a liquid or soft membrane separating the electrodes. The phenomenon relies on the hopping of ions through an otherwise rigid ]. | ||

| ==Mechanism== | ==Mechanism== | ||

| Line 5: | Line 6: | ||

| ==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| In solid electrolytes (glasses or crystals), the ionic conductivity |

In solid electrolytes (glasses or crystals), the ionic conductivity σ<sub>i</sub> can be any value, but it should be much larger than the electronic one. Usually, solids where σ<sub>i</sub> is on the order of 0.0001 to 0.1 Ω<sup>−1</sup> cm<sup>−1</sup> (300 K) are called superionic conductors. | ||

| ===Proton conductors=== | ===Proton conductors=== | ||

| ]s are a special class of solid electrolytes, where ]s act as charge carriers. | ]s are a special class of solid electrolytes, where ]s act as charge carriers. One notable example is ]. | ||

| ===Superionic conductors=== | ===Superionic conductors=== | ||

| ⚫ | Superionic conductors where σ<sub>i</sub> is more than 0.1 Ω<sup>−1</sup> cm<sup>−1</sup> (300 K) and the activation energy for ion transport ''E''<sub>i</sub> is small (about 0.1 eV), are called ]s. The most famous example of advanced superionic conductor-solid electrolyte is ] where σ<sub>i</sub> > 0.25 Ω<sup>−1</sup> cm<sup>−1</sup> and σ<sub>e</sub> ~10<sup>−9</sup> Ω<sup>−1</sup> cm<sup>−1</sup> at 300 K.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Akin |first1=Mert |last2=Wang |first2=Yuchen |last3=Qiao |first3=Xiaoyao |last4=Yan |first4=Zhiwei |last5=Zhou |first5=Xiangyang |title=Effect of relative humidity on the reaction kinetics in rubidium silver iodide based all-solid-state battery |journal=Electrochimica Acta |date=September 2020 |volume=355 |pages=136779 |doi=10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136779|s2cid=225553692 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wang |first1=Yuchen |last2=Akin |first2=Mert |last3=Qiao |first3=Xiaoyao |last4=Yan |first4=Zhiwei |last5=Zhou |first5=Xiangyang |title=Greatly enhanced energy density of all‐solid‐state rechargeable battery operating in high humidity environments |journal=International Journal of Energy Research |date=September 2021 |volume=45 |issue=11 |pages=16794–16805 |doi=10.1002/er.6928|doi-access=free }}</ref> The ] in RbAg<sub>4</sub>I<sub>5</sub> is about 2{{e|-4}} cm<sup>2</sup>/(V•s) at room temperatures.<ref>{{cite journal | ||

| Unlike conventional solid electrolytes and superionic conductors. | |||

| ⚫ | |author1=Stuhrmann C.H.J. |author2=Kreiterling H. |author3=Funke K. |year = 2002 | ||

| ⚫ | Superionic conductors where |

||

| ⚫ | |author1=Stuhrmann C.H.J. |author2=Kreiterling H. |author3=Funke K |year = 2002 | ||

| |title = Ionic Hall effect measured in rubidium silver iodide | |title = Ionic Hall effect measured in rubidium silver iodide | ||

| |journal = Solid State Ionics | |journal = Solid State Ionics | ||

| Line 20: | Line 19: | ||

| |pages = 109–112 | |pages = 109–112 | ||

| |doi = 10.1016/S0167-2738(02)00470-8 | |doi = 10.1016/S0167-2738(02)00470-8 | ||

| }}</ref> The |

}}</ref> The σ<sub>e</sub> – σ<sub>i</sub> systematic diagram distinguishing the different types of solid-state ionic conductors is given in the figure.<ref>{{cite journal | ||

| |author1=Александр Деспотули |author2=Александра Андреева |year = 2007 | |author1=Александр Деспотули |author2=Александра Андреева |year = 2007 | ||

| |script-title=ru:Высокоёмкие конденсаторы для 0,5 вольтовой наноэлектроники будущего | |script-title=ru:Высокоёмкие конденсаторы для 0,5 вольтовой наноэлектроники будущего | ||

| |journal = Современная Электроника | |journal = Современная Электроника | ||

| |volume = | |||

| |issue = 7 | |issue = 7 | ||

| |pages = 24–29 | |pages = 24–29 | ||

| ⚫ | |language = ru | ||

| |location =http://www.nanometer.ru/2007/10/17/nanoionnie_superkondensatori_4879/PROP_FILE_files_1/Despotuli_Andreeva_Modern_Electronics_2007.pdf | |||

| ⚫ | |language = |

||

| |format = ] | |||

| |accessdate = 2007-11-02 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{cite journal | {{cite journal | ||

| |author1=Alexander Despotuli |author2=Alexandra Andreeva | |

|author1=Alexander Despotuli |author2=Alexandra Andreeva |year = 2007 | ||

| |year = 2007 | |||

| |title = High-capacity capacitors for 0.5 voltage nanoelectronics of the future | |title = High-capacity capacitors for 0.5 voltage nanoelectronics of the future | ||

| |journal = Modern Electronics | |journal = Modern Electronics | ||

| |issue = 7 | |issue = 7 | ||

| |pages = 24–29 | |pages = 24–29 | ||

| ⚫ | }}</ref><ref name=Despotuli>{{cite journal |last1=Despotuli |first1=A.L. |last2=Andreeva |first2=A.V. |title= A Short Review on Deep-Sub-Voltage Nanoelectronics and Related Technologies |journal=International Journal of Nanoscience|volume=8 |issue=4&5 |pages=389–402 |date= January 2009 |doi= 10.1142/S0219581X09006328|bibcode = 2009IJN.....8..389D | ||

| |location = http://www.nanometer.ru/2007/10/17/nanoionnie_superkondensatori_4879/PROP_FILE_files_2/Despotuli_Andreeva_Modern_Electronics_2007(ENG).pdf | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| |format = ] | |||

| |accessdate = 2007-11-02 | |||

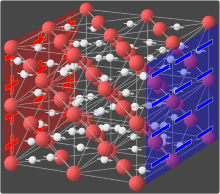

| ⚫ | ]s (MIECs). 3 and 4 are superionic conductors (SICs), i.e. materials with σ<sub>i</sub> > 0.001 Ω<sup>−1</sup>cm<sup>−1</sup>. 5 and 6 are advanced superionic conductors (AdSICs), where σ<sub>i</sub> > 10<sup>−1</sup> Ω<sup>−1</sup>cm<sup>−1</sup> (300 K), energy activation ''E''<sub>i</sub> about 0.1 eV. 7 and 8 are hypothetical AdSIC with ''E''i ≈ ''k''<sub>B</sub>T ≈0.03 eV (300 К).]] | ||

| ⚫ | }}</ref><ref name=Despotuli>{{cite journal |last1=Despotuli |first1=A.L. |last2=Andreeva |first2=A.V. |title= A Short Review on Deep-Sub-Voltage Nanoelectronics and Related Technologies |journal= |

||

| ⚫ | [[ |

||

| ⚫ | No clear examples have been described as yet, of fast ion conductors in the hypothetical advanced superionic conductors class (areas 7 and 8 in the classification plot). However, in crystal structure of several superionic conductors, e.g. in the minerals of the pearceite-polybasite group, the large structural fragments with activation energy of ion transport ''E''<sub>i</sub> < ''k''<sub>B</sub>T (300 К) had been discovered in 2006.<ref>{{cite journal |last= Bindi |first= L. |author2= Evain M. |title= Fast ion conduction character and ionic phase-transitions in disordered crystals: the complex case of the minerals of the pearceite– polybasite group |journal= Phys Chem Miner |year=2006 |volume=33 |pages=677–690 |doi=10.1007/s00269-006-0117-7|bibcode = 2006PCM....33..677B|issue=10|s2cid= 95315848 }}</ref> | ||

| ''E''i about 0.1 eV, Ω<sub>i</sub> >>Ω<sub>e</sub>; 7 and 8 – hypothetical AdSIC with ''E''i ≈ ''k''<sub>B</sub>T ≈0.03 eV (300 К); 8 – hypothetical AdSIC and simultaneously SE.]] | |||

| ⚫ | No clear examples have been described as yet, of fast ion conductors in the hypothetical advanced superionic conductors class (areas 7 and 8 in the classification plot). However, in crystal structure of several superionic conductors, e.g. in the minerals of the pearceite-polybasite group, the large structural fragments with activation energy of ion transport ''E''i |

||

| ==Examples== | ==Examples== | ||

| ===Zirconia-based materials=== | ===Zirconia-based materials=== | ||

| A common solid electrolyte is ], YSZ. This material is prepared by ] Y<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> into ]. Oxide ions typically migrate only slowly in solid Y<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> and in ZrO<sub>2</sub>, but in YSZ, the conductivity of oxide increases dramatically. These materials are used to allow |

A common solid electrolyte is ], YSZ. This material is prepared by ] Y<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> into ]. Oxide ions typically migrate only slowly in solid Y<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> and in ZrO<sub>2</sub>, but in YSZ, the conductivity of oxide increases dramatically. These materials are used to allow oxygen to move through the solid in certain kinds of fuel cells. Zirconium dioxide can also be doped with ] to give an oxide conductor that is used in ]s in automobile controls. Upon doping only a few percent, the diffusion constant of oxide increases by a factor of ~1000.<ref>Shriver, D. F.; Atkins, P. W.; Overton, T. L.; Rourke, J. P.; Weller, M. T.; Armstrong, F. A. “Inorganic Chemistry” W. H. Freeman, New York, 2006. {{ISBN|0-7167-4878-9}}.</ref> | ||

| Other conductive ]s function as ion conductors. One example is ], (Na<sub>3</sub>Zr<sub>2</sub>Si<sub>2</sub>PO<sub>12</sub>), a sodium super-ionic conductor | Other conductive ]s function as ion conductors. One example is ], (Na<sub>3</sub>Zr<sub>2</sub>Si<sub>2</sub>PO<sub>12</sub>), a sodium super-ionic conductor | ||

| ===beta-Alumina=== | ===beta-Alumina=== | ||

| Another example of a popular fast ion conductor is ].<ref>{{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd}}</ref> Unlike the usual ], this modification has a layered structure with open galleries separated by pillars. Sodium ions (Na< |

Another example of a popular fast ion conductor is ].<ref>{{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd}}</ref> Unlike the usual ], this modification has a layered structure with open galleries separated by pillars. Sodium ions (Na<sup>+</sup>) migrate through this material readily since the oxide framework provides an ionophilic, non-reducible medium. This material is considered as the sodium ion conductor for the ]. | ||

| ===Fluoride ion conductors=== | ===Fluoride ion conductors=== | ||

| Line 61: | Line 54: | ||

| ===Iodides=== | ===Iodides=== | ||

| A textbook example of a fast ion conductor is ] (AgI). Upon heating the solid to 146 °C, this material adopts the alpha-polymorph. In this form, the iodide ions form a rigid cubic framework, and the Ag+ centers are molten. The electrical conductivity of the solid increases by 4000x. Similar behavior is observed for ] (CuI), ] ( |

A textbook example of a fast ion conductor is ] (AgI). Upon heating the solid to 146 °C, this material adopts the alpha-polymorph. In this form, the iodide ions form a rigid cubic framework, and the Ag+ centers are molten. The electrical conductivity of the solid increases by 4000x. Similar behavior is observed for ] (CuI), ] (RbAg<sub>4</sub>I<sub>5</sub>),<ref>{{cite journal |title=Effect of relative humidity on the reaction kinetics in rubidium silver iodide based all-solid-state battery |journal=Electrochimica Acta |date=20 September 2020 |volume=355 |pages=136779 |doi=10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136779 |last1=Akin |first1=Mert |last2=Wang |first2=Yuchen |last3=Qiao |first3=Xiaoyao |last4=Yan |first4=Zhiwei |last5=Zhou |first5=Xiangyang |s2cid=225553692 }}</ref> and Ag<sub>2</sub>HgI<sub>4</sub>. | ||

| ===Other Inorganic materials=== | ===Other Inorganic materials=== | ||

| *], conductive for Ag<sup>+</sup> ions, used in some ]s | *], conductive for Ag<sup>+</sup> ions, used in some ]s | ||

| *], conductive for Cl<sup>−</sup> ions at higher temperatures<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Matsumoto |first=Hiroshige |last2=Miyake |first2=Takako |last3=Iwahara |first3=Hiroyasu |date=2001-05-01 |title=Chloride ion conduction in PbCl2-PbO system |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025540801005931 |journal=Materials Research Bulletin |volume=36 |issue=7 |pages=1177–1184 |doi=10.1016/S0025-5408(01)00593-1 |issn=0025-5408}}</ref> | |||

| *], conductive at higher temperatures | |||

| *Some ] ceramics – ], ] – conductive for O<sup>2−</sup> ions | *Some ] ceramics – ], ] – conductive for O<sup>2−</sup> ions | ||

| *Zr( |

*<chem>Zr(HPO4)2.\mathit{n}H2O</chem> – conductive for H<sup>+</sup> ions | ||

| * |

*<chem>UO2HPO4.4H2O</chem> (hydrogen uranyl phosphate tetrahydrate) – conductive for H<sup>+</sup> ions | ||

| * ] – conductive for O<sup>2−</sup> ions | |||

| ===Organic materials=== | ===Organic materials=== | ||

| *Many ]s, such ]s, ], etc. are fast ion conductors<ref name="dry">{{cite web|url=http://www.evworld.com/article.cfm?storyid=933 |title=The Roll-to-Roll Battery Revolution |publisher=Ev World |date |

*Many ]s, such ]s, ], etc. are fast ion conductors<ref name="dry">{{cite web |url=http://www.evworld.com/article.cfm?storyid=933 |title=The Roll-to-Roll Battery Revolution |publisher=Ev World |access-date=2010-08-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110710210351/http://www.evworld.com/article.cfm?storyid=933 |archive-date=2011-07-10 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.electacta.2011.06.014| title = The effect of additive of Lewis acid type on lithium–gel electrolyte characteristics| journal = Electrochimica Acta| volume = 57| pages = 58–65| year = 2011| last1 = Perzyna | first1 = K. | last2 = Borkowska | first2 = R. | last3 = Syzdek | first3 = J. A. | last4 = Zalewska | first4 = A. | last5 = Wieczorek | first5 = W. A. A. }}</ref> | ||

| *A salt dissolved in a polymer – e.g. ] in ]<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Syzdek | first1 = J. A. | last2 = Armand | first2 = M. | last3 = Marcinek | first3 = M. | last4 = Zalewska | first4 = A. | last5 = Żukowska | first5 = G. Y. | last6 = Wieczorek | first6 = W. A. A. | doi = 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.04.025 | title = Detailed studies on the fillers modification and their influence on composite, poly(oxyethylene)-based polymeric electrolytes | journal = Electrochimica Acta | volume = 55 | issue = 4 | pages = 1314 | year = 2010 |

*A salt dissolved in a polymer – e.g. ] in ]<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Syzdek | first1 = J. A. | last2 = Armand | first2 = M. | last3 = Marcinek | first3 = M. | last4 = Zalewska | first4 = A. | last5 = Żukowska | first5 = G. Y. | last6 = Wieczorek | first6 = W. A. A. | doi = 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.04.025 | title = Detailed studies on the fillers modification and their influence on composite, poly(oxyethylene)-based polymeric electrolytes | journal = Electrochimica Acta | volume = 55 | issue = 4 | pages = 1314 | year = 2010 }}</ref> | ||

| *]s and ]s – e.g. ], a ] | *]s and ]s – e.g. ], a ] | ||

| Line 85: | Line 79: | ||

| |pages = 1123–1128 | |pages = 1123–1128 | ||

| |doi = 10.1063/1.1699148 | |doi = 10.1063/1.1699148 | ||

| |bibcode = 1953JChPh..21.1123L }}</ref> | |bibcode = 1953JChPh..21.1123L |doi-access = free | ||

| }}</ref> | |||

| As a space-charge layer has nanometer thickness, the effect is directly related to ] (nanoionics-I). Lehovec's effect is used as a basis for developing ] for portable lithium batteries and fuel cells. | As a space-charge layer has nanometer thickness, the effect is directly related to ] (nanoionics-I). Lehovec's effect is used as a basis for developing ] for portable lithium batteries and fuel cells. | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:37, 19 January 2025

In materials science, fast ion conductors are solid conductors with highly mobile ions. These materials are important in the area of solid state ionics, and are also known as solid electrolytes and superionic conductors. These materials are useful in batteries and various sensors. Fast ion conductors are used primarily in solid oxide fuel cells. As solid electrolytes they allow the movement of ions without the need for a liquid or soft membrane separating the electrodes. The phenomenon relies on the hopping of ions through an otherwise rigid crystal structure.

Mechanism

Fast ion conductors are intermediate in nature between crystalline solids which possess a regular structure with immobile ions, and liquid electrolytes which have no regular structure and fully mobile ions. Solid electrolytes find use in all solid-state supercapacitors, batteries, and fuel cells, and in various kinds of chemical sensors.

Classification

In solid electrolytes (glasses or crystals), the ionic conductivity σi can be any value, but it should be much larger than the electronic one. Usually, solids where σi is on the order of 0.0001 to 0.1 Ω cm (300 K) are called superionic conductors.

Proton conductors

Proton conductors are a special class of solid electrolytes, where hydrogen ions act as charge carriers. One notable example is superionic water.

Superionic conductors

Superionic conductors where σi is more than 0.1 Ω cm (300 K) and the activation energy for ion transport Ei is small (about 0.1 eV), are called advanced superionic conductors. The most famous example of advanced superionic conductor-solid electrolyte is RbAg4I5 where σi > 0.25 Ω cm and σe ~10 Ω cm at 300 K. The Hall (drift) ionic mobility in RbAg4I5 is about 2×10 cm/(V•s) at room temperatures. The σe – σi systematic diagram distinguishing the different types of solid-state ionic conductors is given in the figure.

No clear examples have been described as yet, of fast ion conductors in the hypothetical advanced superionic conductors class (areas 7 and 8 in the classification plot). However, in crystal structure of several superionic conductors, e.g. in the minerals of the pearceite-polybasite group, the large structural fragments with activation energy of ion transport Ei < kBT (300 К) had been discovered in 2006.

Examples

Zirconia-based materials

A common solid electrolyte is yttria-stabilized zirconia, YSZ. This material is prepared by doping Y2O3 into ZrO2. Oxide ions typically migrate only slowly in solid Y2O3 and in ZrO2, but in YSZ, the conductivity of oxide increases dramatically. These materials are used to allow oxygen to move through the solid in certain kinds of fuel cells. Zirconium dioxide can also be doped with calcium oxide to give an oxide conductor that is used in oxygen sensors in automobile controls. Upon doping only a few percent, the diffusion constant of oxide increases by a factor of ~1000.

Other conductive ceramics function as ion conductors. One example is NASICON, (Na3Zr2Si2PO12), a sodium super-ionic conductor

beta-Alumina

Another example of a popular fast ion conductor is beta-alumina solid electrolyte. Unlike the usual forms of alumina, this modification has a layered structure with open galleries separated by pillars. Sodium ions (Na) migrate through this material readily since the oxide framework provides an ionophilic, non-reducible medium. This material is considered as the sodium ion conductor for the sodium–sulfur battery.

Fluoride ion conductors

Lanthanum trifluoride (LaF3) is conductive for F ions, used in some ion selective electrodes. Beta-lead fluoride exhibits a continuous growth of conductivity on heating. This property was first discovered by Michael Faraday.

Iodides

A textbook example of a fast ion conductor is silver iodide (AgI). Upon heating the solid to 146 °C, this material adopts the alpha-polymorph. In this form, the iodide ions form a rigid cubic framework, and the Ag+ centers are molten. The electrical conductivity of the solid increases by 4000x. Similar behavior is observed for copper(I) iodide (CuI), rubidium silver iodide (RbAg4I5), and Ag2HgI4.

Other Inorganic materials

- Silver sulfide, conductive for Ag ions, used in some ion selective electrodes

- Lead(II) chloride, conductive for Cl ions at higher temperatures

- Some perovskite ceramics – strontium titanate, strontium stannate – conductive for O ions

- – conductive for H ions

- (hydrogen uranyl phosphate tetrahydrate) – conductive for H ions

- Cerium(IV) oxide – conductive for O ions

Organic materials

- Many gels, such polyacrylamides, agar, etc. are fast ion conductors

- A salt dissolved in a polymer – e.g. lithium perchlorate in polyethylene oxide

- Polyelectrolytes and Ionomers – e.g. Nafion, a H conductor

History

The important case of fast ionic conduction is one in a surface space-charge layer of ionic crystals. Such conduction was first predicted by Kurt Lehovec. As a space-charge layer has nanometer thickness, the effect is directly related to nanoionics (nanoionics-I). Lehovec's effect is used as a basis for developing nanomaterials for portable lithium batteries and fuel cells.

See also

References

- Akin, Mert; Wang, Yuchen; Qiao, Xiaoyao; Yan, Zhiwei; Zhou, Xiangyang (September 2020). "Effect of relative humidity on the reaction kinetics in rubidium silver iodide based all-solid-state battery". Electrochimica Acta. 355: 136779. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136779. S2CID 225553692.

- Wang, Yuchen; Akin, Mert; Qiao, Xiaoyao; Yan, Zhiwei; Zhou, Xiangyang (September 2021). "Greatly enhanced energy density of all‐solid‐state rechargeable battery operating in high humidity environments". International Journal of Energy Research. 45 (11): 16794–16805. doi:10.1002/er.6928.

- Stuhrmann C.H.J.; Kreiterling H.; Funke K. (2002). "Ionic Hall effect measured in rubidium silver iodide". Solid State Ionics. 154–155: 109–112. doi:10.1016/S0167-2738(02)00470-8.

- Александр Деспотули; Александра Андреева (2007). Высокоёмкие конденсаторы для 0,5 вольтовой наноэлектроники будущего. Современная Электроника (in Russian) (7): 24–29. Alexander Despotuli; Alexandra Andreeva (2007). "High-capacity capacitors for 0.5 voltage nanoelectronics of the future". Modern Electronics (7): 24–29.

- Despotuli, A.L.; Andreeva, A.V. (January 2009). "A Short Review on Deep-Sub-Voltage Nanoelectronics and Related Technologies". International Journal of Nanoscience. 8 (4&5): 389–402. Bibcode:2009IJN.....8..389D. doi:10.1142/S0219581X09006328.

- Bindi, L.; Evain M. (2006). "Fast ion conduction character and ionic phase-transitions in disordered crystals: the complex case of the minerals of the pearceite– polybasite group". Phys Chem Miner. 33 (10): 677–690. Bibcode:2006PCM....33..677B. doi:10.1007/s00269-006-0117-7. S2CID 95315848.

- Shriver, D. F.; Atkins, P. W.; Overton, T. L.; Rourke, J. P.; Weller, M. T.; Armstrong, F. A. “Inorganic Chemistry” W. H. Freeman, New York, 2006. ISBN 0-7167-4878-9.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Akin, Mert; Wang, Yuchen; Qiao, Xiaoyao; Yan, Zhiwei; Zhou, Xiangyang (20 September 2020). "Effect of relative humidity on the reaction kinetics in rubidium silver iodide based all-solid-state battery". Electrochimica Acta. 355: 136779. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136779. S2CID 225553692.

- Matsumoto, Hiroshige; Miyake, Takako; Iwahara, Hiroyasu (2001-05-01). "Chloride ion conduction in PbCl2-PbO system". Materials Research Bulletin. 36 (7): 1177–1184. doi:10.1016/S0025-5408(01)00593-1. ISSN 0025-5408.

- "The Roll-to-Roll Battery Revolution". Ev World. Archived from the original on 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- Perzyna, K.; Borkowska, R.; Syzdek, J. A.; Zalewska, A.; Wieczorek, W. A. A. (2011). "The effect of additive of Lewis acid type on lithium–gel electrolyte characteristics". Electrochimica Acta. 57: 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2011.06.014.

- Syzdek, J. A.; Armand, M.; Marcinek, M.; Zalewska, A.; Żukowska, G. Y.; Wieczorek, W. A. A. (2010). "Detailed studies on the fillers modification and their influence on composite, poly(oxyethylene)-based polymeric electrolytes". Electrochimica Acta. 55 (4): 1314. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2009.04.025.

- Lehovec, Kurt (1953). "Space-charge layer and distribution of lattice defects at the surface of ionic crystals". Journal of Chemical Physics. 21 (7): 1123–1128. Bibcode:1953JChPh..21.1123L. doi:10.1063/1.1699148.

– conductive for H ions

– conductive for H ions (hydrogen uranyl phosphate tetrahydrate) – conductive for H ions

(hydrogen uranyl phosphate tetrahydrate) – conductive for H ions