| Revision as of 20:54, 30 April 2011 editCyclops12345 (talk | contribs)6 edits →See also← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:35, 17 January 2025 edit undoAdakiko (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers88,803 editsm Reverted edits by 176.139.146.95 (talk) (HG) (3.4.13)Tags: Huggle Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Psychological ethological theory about human relationships}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| '''Attachment theory''' describes the dynamics of long-term ] especially as in families and life-long friends. Its most important tenet is that an infant needs to develop a relationship with at least one primary caregiver for social and emotional development to occur normally, and that further relationships build on the patterns developed in the first relationships. Attachment theory is an interdisciplinary study encompassing the fields of ], ]ary, and ] theory. It began as a result of experiences during World War II in England when children were evacuated from cities to escape from bombing. Child care professionals caring for separated or orphaned children couldn't help but be aware of the children's profound grief and distress. Immediately after WWII, homeless and orphaned children presented many difficulties,<ref name="Cassidy"/> and ] and ] ] was asked by the UN to write a pamphlet on the matter. Later he went on to formulate attachment theory. | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=November 2024}} | |||

| Infants become attached to adults who are sensitive and responsive in ]s with them, and who remain as consistent caregivers for some months during the period from about six months to two years of age. When an infant begins to crawl and walk they begin to use attachment figures (familiar people) as a secure base to explore from and return to. Parental responses lead to the development of patterns of attachment; these, in turn, lead to internal working models which will guide the individual's perceptions, emotions, thoughts and expectations in later relationships.<ref name="Bretherton/Mul">{{cite encyclopedia|author= Bretherton I, Munholland KA|title= Internal Working Models in Attachment Relationships: A Construct Revisited|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications|year=1999|editor= Cassidy J, Shaver PR|location=New York|publisher= Guilford Press|isbn= 1572300876|pages=89–114}}</ref> Separation ] or grief following the loss of an attachment figure is considered to be a normal and ] response for an attached infant. These behaviours may have evolved because they increase the probability of survival of the child.<ref>Prior and Glaser p. 17.</ref> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2024}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Attachment theory''' is a ] and ]ary framework concerning the ], particularly the importance of early bonds between infants and their primary caregivers. Developed by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst ] (1907–90), the theory posits that infants need to form a close relationship with at least one primary caregiver to ensure their survival, and to develop healthy social and emotional functioning.<ref name="Cassidy">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1999 |title=The Nature of a Child's Ties |encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications |publisher=Guilford Press |location=New York | veditors = Cassidy J, Shaver PR |pages= |isbn=1-57230-087-6 | vauthors = Cassidy J |url=https://archive.org/details/handbookofattach0000unse/page/3 }}</ref><ref name="Abrams Turner Baumann Karel 2013 pp. 149–155">{{cite book | last1=Abrams | first1=David B. | last2=Turner | first2=J. Rick | last3=Baumann | first3=Linda C. | last4=Karel | first4=Alyssa | last5=Collins | first5=Susan E. | last6=Witkiewitz | first6=Katie | last7=Fulmer | first7=Terry | last8=Tanenbaum | first8=Molly L. | last9=Commissariat | first9=Persis | last10=Kupperman | first10=Elyse | last11=Baek | first11=Rachel N. | last12=Gonzalez | first12=Jeffrey S. | last13=Brandt | first13=Nicole | last14=Flurie | first14=Rachel | last15=Heaney | first15=Jennifer | last16=Kline | first16=Christopher | last17=Carroll | first17=Linda | last18=Upton | first18=Jane | last19=Buchain | first19=Patrícia Cardoso | last20=Vizzotto | first20=Adriana Dias Barbosa | last21=Martini de Oliveira | first21=Alexandra | last22=Ferraz Alves | first22=Tania C. T. | last23=Cordeiro | first23=Quirino | last24=Cohen | first24=Lorenzo | last25=Garcia | first25=M. Kay | last26=Marcano-Reik | first26=Amy Jo | last27=Ye | first27=Siqin | last28=Gidron | first28=Yori | last29=Gellman | first29=Marc D. | last30=Howren | first30=M. Bryant | last31=Harlapur | first31=Manjunath | last32=Shimbo | first32=Daichi | last33=Ohta | first33=Keisuke | last34=Yahagi | first34=Naoya | last35=Franzmann | first35=Elizabeth | last36=Singh | first36=Abanish | last37=Baumann | first37=Linda C. | last38=Karel | first38=Alyssa | last39=Johnson | first39=Debra | last40=Clarke | first40=Benjamin L. | last41=Johnson | first41=Debra | last42=Millstein | first42=Rachel | last43=Niven | first43=Karen | last44=Niven | first44=Karen | last45=Miles | first45=Eleanor | last46=Turner | first46=J. Rick | last47=Resnick | first47=Barbara | last48=Gidron | first48=Yori | last49=Lennon | first49=Carter A. | last50=DeMartini | first50=Kelly S. | last51=MacGregor | first51=Kristin L. | last52=Collins | first52=Susan E. | last53=Kirouac | first53=Megan | last54=Turner | first54=J. Rick | last55=Singh | first55=Abanish | last56=Gidron | first56=Yori | last57=Yamamoto | first57=Yoshiharu | last58=Nater | first58=Urs M. | last59=Nisly | first59=Nicole | last60=Johnson | first60=Debra | last61=Johnston | first61=Derek | last62=Zanstra | first62=Ydwine | last63=Johnston | first63=Derek | last64=Kim | first64=Youngmee | last65=Matheson | first65=Della | last66=McInroy | first66=Brooke | last67=France | first67=Christopher | last68=Fukudo | first68=Shin | last69=Tsuchiya | first69=Emiko | last70=Katayori | first70=Yoko | last71=Deschner | first71=Martin | last72=Anderson | first72=Norman B. | last73=Barrett | first73=Chad | last74=Lumley | first74=Mark A. | last75=Oberleitner | first75=Lindsay | last76=Bongard | first76=Stephan | last77=Ye | first77=Siqin | last78=Marcano-Reik | first78=Amy Jo | last79=Hurley | first79=Seth | last80=Hurley | first80=Seth | last81=Patino-Fernandez | first81=Anna Maria | last82=Phillips | first82=Anna C. | last83=Akechi | first83=Tatsuo | last84=Phillips | first84=Anna C. | last85=Marcano-Reik | first85=Amy Jo | last86=Brandt | first86=Nicole | last87=Flurie | first87=Rachel | last88=Aldred | first88=Sarah | last89=Lavoie | first89=Kim | last90=Harlapur | first90=Manjunath | last91=Shimbo | first91=Daichi | last92=Jansen | first92=Kate L. | last93=Fortenberry | first93=Katherine T. | last94=Clark | first94=Molly S. | last95=Millstein | first95=Rachel | last96=Okuyama | first96=Toru | last97=Whang | first97=William | last98=Al’Absi | first98=Mustafa | last99=Li | first99=Bingshuo | last100=Gidron | first100=Yori | last101=Turner | first101=J. Rick | last102=Pulgaron | first102=Elizabeth R. | last103=Wile | first103=Diana | last104=Baumann | first104=Linda C. | last105=Karel | first105=Alyssa | last106=Schroeder | first106=Beth | last107=Davis | first107=Mary C. | last108=Zautra | first108=Alex | last109=Stark | first109=Shannon L. | last110=Whang | first110=William | last111=Soto | first111=Ana Victoria | last112=Gidron | first112=Yori | last113=Wheeler | first113=Anthony J. | last114=DeBerard | first114=Scott | last115=Allen | first115=Josh | last116=Mitani | first116=Akihisa | last117=Mitani | first117=Akihisa | last118=Pulgaron | first118=Elizabeth R. | last119=Mitani | first119=Akihisa | last120=Carter | first120=Jennifer | last121=Whang | first121=William | last122=Schroeder | first122=Beth | last123=Hicks | first123=Angela M. | last124=Korbel | first124=Carolyn | last125=Baldwin | first125=Austin S. | last126=Spink | first126=Kevin S. | last127=Nickel | first127=Darren | last128=Richter | first128=Michael | last129=Wright | first129=Rex A. | last130=Thayer | first130=Julian F. | last131=Richter | first131=Michael | last132=Wright | first132=Rex A. | last133=Wiebe | first133=Deborah J. | title=Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine | chapter=Attachment Theory | publisher=Springer New York | publication-place=New York, NY | year=2013 | doi=10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_939 | pages=149–155| isbn=978-1-4419-1004-2 |quote=Bowlby (1969, 1988) described an attachment as an emotional bond that is characterized by the tendency to seek out and maintain proximity to a specific attachment figure, particularly during times of distress.}}</ref> | |||

| Infant ] associated with attachment is primarily the seeking of ] to an attachment figure. To formulate a comprehensive theory of the nature of early attachments, Bowlby explored a range of fields, including ], ] (a branch of ]), ], and the fields of ] and ].<ref name="simpson">{{cite encyclopaedia|author=Simpson JA|title=Attachment Theory in Modern Evolutionary Perspective|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications|editor= Cassidy J, Shaver PR|year = 1999|pages=115–40|publisher=Guilford Press|isbn=1572300876|location=New York}}</ref> After preliminary papers from 1958 onwards, Bowlby published a complete study in 3 volumes ''Attachment and Loss'' (1969–82). | |||

| Pivotal aspects of attachment theory include the observation that infants seek proximity to attachment figures, especially during stressful situations.<ref name="Abrams Turner Baumann Karel 2013 pp. 149–155"/><ref name="Brimhall Haralson 2017 pp. 1–3">{{cite book | last1=Brimhall | first1=Andrew S. | last2=Haralson | first2=David M. | title=Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy | chapter=Bonds in Couple and Family Therapy | publisher=Springer International Publishing | publication-place=Cham | year=2017 | isbn=978-3-319-15877-8 | doi=10.1007/978-3-319-15877-8_513-1 | pages=1–3 | quote=Bond is an emotional attachment between one or more individuals. To be considered an attachment bond, the relationship must have four defining characteristics: proximity maintenance, separation distress, safe haven, and secure base.}}</ref> Secure attachments are formed when caregivers are sensitive and responsive in ]s, and consistently present, particularly between the ages of six months and two years. As children grow, they use these attachment figures as a secure base from which to explore the world and return to for comfort. The interactions with caregivers form patterns of attachment, which in turn create internal working models that influence future relationships.<ref name="Bretherton/Mul">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1999 |title=Internal Working Models in Attachment Relationships: A Construct Revisited |encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment:Theory, Research and Clinical Applications |publisher=Guilford Press |location=New York | veditors = Cassidy J, Shaver PR |pages= |isbn=1-57230-087-6 |author=Bretherton I, Munholland KA |url=https://archive.org/details/handbookofattach0000unse/page/89 }}</ref> Separation anxiety or grief following the loss of an attachment figure is considered to be a normal and adaptive response for an attached infant.{{sfn|Prior|Glaser|2006|p=17}} | |||

| Research by ] ] in the 1960s and 70s reinforced the basic concepts, introduced the concept of the "secure base" and developed a theory of a number of attachment patterns in infants: secure attachment, avoidant attachment and anxious attachment.<ref name="Bretherton">{{cite journal|author=Bretherton I|title=The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth|year=1992|journal=Developmental Psychology|volume= 28|page=759|doi=10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759|issue=5}}</ref> A fourth pattern, disorganized attachment, was identified later. | |||

| Research by ] ] in the 1960s and 70s expanded on Bowlby's work, introducing the concept of the "secure base", impact of maternal responsiveness and sensitivity to infant distress, and identified attachment patterns in infants: secure, avoidant, anxious, and disorganized attachment.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Bernard |first1=Kristin |last2=Meade |first2=Eb |last3=Dozier |first3=Mary |date=November 2013 |title=Parental synchrony and nurturance as targets in an attachment based intervention: building upon Mary Ainsworth's insights about mother–infant interaction |journal=Attachment & Human Development |language=en |volume=15 |issue=5–6 |pages=507–523 |doi=10.1080/14616734.2013.820920 |issn=1461-6734 |pmc=3855268 |pmid=24299132}}</ref><ref name="Bretherton">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bretherton I |year=1992 |title=The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_developmental-psychology_1992-09_28_5/page/759 |journal=Developmental Psychology |volume=28 |issue=5 |pages=759–775 |doi=10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.759}}</ref> In the 1980s, attachment theory was extended to adult relationships and ], making it applicable beyond early childhood.<ref name="Hazan, Shaver, 1987">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hazan C, Shaver P | s2cid = 2280613 | title = Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_journal-of-personality-and-social-psychology_1987-03_52_3/page/511 | journal = Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | volume = 52 | issue = 3 | pages = 511–24 | date = March 1987 | pmid = 3572722 | doi = 10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511 }}</ref> Bowlby's theory integrated concepts from ], ], ], ], and ], and was fully articulated in his trilogy, ''Attachment and Loss'' (1969–82).<ref name="simpson">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1999 |title=Attachment Theory in Modern Evolutionary Perspective |encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment:Theory, Research and Clinical Applications |publisher=Guilford Press |location=New York |veditors = Cassidy J, Shaver PR |pages= |isbn=1-57230-087-6 |author=Simpson JA |url=https://archive.org/details/handbookofattach0000unse/page/115 }}</ref> | |||

| In the 1980s, the theory was extended to ].<ref name="Hazan, Shaver,1987"/> Other interactions may be construed as including components of attachment behaviour; these include peer relationships at all ages, romantic and sexual attraction and responses to the care needs of infants or the sick and elderly. | |||

| While initially criticized by academic psychologists and psychoanalysts,<ref name="Rutter 95" /> attachment theory has become a dominant approach to understanding early social development and has generated extensive research.<ref name="Schaffer" /> Despite some criticisms related to temperament, social complexity, and the limitations of discrete attachment patterns, the theory's core concepts have been widely accepted and have influenced therapeutic practices and social and childcare policies.<ref name="Rutter 95" /><ref name="BZL" /> | |||

| ==Attachment== | ==Attachment== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Within attachment theory, ''attachment'' means an ] or tie between an individual and an attachment figure (usually a caregiver). Such bonds may be reciprocal between two adults, but between a child and a caregiver these bonds are based on the child's need for safety, security and |

Within attachment theory, ''attachment'' means an ] or tie between an individual and an attachment figure (usually a caregiver/guardian). Such bonds may be reciprocal between two adults, but between a child and a caregiver, these bonds are based on the child's need for safety, security, and protection—which is most important in infancy and childhood.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Murphy |first1=Anne |last2=Steele |first2=Miriam |last3=Dube |first3=Shanta Rishi |last4=Bate |first4=Jordan |last5=Bonuck |first5=Karen |last6=Meissner |first6=Paul |last7=Goldman |first7=Hannah |last8=Steele |first8=Howard |date=2014 |title=Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire and Adult Attachment Interview (AAI): Implications for parent child relationships |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0145213413002561 |journal=Child Abuse & Neglect |language=en |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=224–233 |doi=10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004|pmid=24670331 |s2cid=3919568 }}</ref> Attachment theory is not an exhaustive description of human relationships, nor is it synonymous with love and affection, although these may indicate that bonds exist. In child-to-adult relationships, the child's tie is called the "attachment" and the caregiver's reciprocal equivalent is referred to as the "care-giving bond".<ref name=pg15>] p. 15.</ref> The theory proposes that children attach to carers instinctively,<ref name="BrethQuote">{{cite news|author=Bretherton I|title=The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth|year=1992|quote= begin by noting that organisms at different levels of the phylogenetic scale regulate instinctive behaviour in distinct ways, ranging from primitive reflex-like "fixed action patterns" to complex plan hierarchies with subgoals and strong learning components. In the most complex organisms, instinctive behaviours may be "goal-corrected" with continual on-course adjustments (such as a bird of prey adjusting its flight to the movements of the prey). The concept of cybernetically controlled behavioural systems organized as plan hierarchies (Miller, Galanter, and Pribram, 1960) thus came to replace Freud's concept of drive and instinct. Such systems regulate behaviours in ways that need not be rigidly innate, but – depending on the organism – can adapt in greater or lesser degrees to changes in environmental circumstances, provided that these do not deviate too much from the organism's environment of evolutionary adaptedness. Such flexible organisms pay a price, however, because adaptable behavioural systems can more easily be subverted from their optimal path of development. For humans, Bowlby speculates, the environment of evolutionary adaptedness probably resembles that of present-day hunter-gatherer societies.}}</ref> for the purpose of survival and, ultimately, genetic replication.<ref name=pg15/> The biological aim is survival and the psychological aim is security.<ref name="Schaffer"/> The relationship that a child has with their attachment figure is especially important in threatening situations. Having access to a secure figure decreases fear in children when they are presented with threatening situations. Not only is having a decreased level of fear important for general mental stability, but it also implicates how children might react to threatening situations. The presence of a supportive attachment figure is especially important in a child's developmental years.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Stupica |first1=Brandi |last2=Brett |first2=Bonnie E. |last3=Woodhouse |first3=Susan S. |last4=Cassidy |first4=Jude |date=July 2019 |title=Attachment Security Priming Decreases Children's Physiological Response to Threat |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.13009 |journal=Child Development |language=en |volume=90 |issue=4 |pages=1254–1271 |doi=10.1111/cdev.13009|pmid=29266177 }}</ref> In addition to support, attunement (accurate understanding and emotional connection) is crucial in a caregiver-child relationship. If the caregiver is poorly attuned to the child, the child may grow to feel misunderstood and anxious.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-04-04 |title=Attunement |url=https://www.evolveinnature.com/blog/2023/3/7-attunement-the-real-language-of-love |access-date=2023-08-23 |website=Evolve In Nature |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| Infants form attachments to any consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with them. The quality of |

Infants form attachments to ''any'' consistent caregiver who is sensitive and responsive in social interactions with them. The quality of social engagement is more influential than the amount of time spent. The biological mother is the usual principal attachment figure, but the role can be assumed by anyone who consistently behaves in a "mothering" way over a period of time. Within attachment theory, this means a set of behaviours that involves engaging in lively social interaction with the infant and responding readily to signals and approaches.<ref>Bowlby (1969) p. 365.</ref> Nothing in the theory suggests that fathers are not equally likely to become principal attachment figures if they provide most of the child care and related social interaction.<ref>] p. 69.</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Cosentino|first=Ashley|date=5 September 2017|title=Viewing fathers as attachment figures|url=https://ct.counseling.org/2017/09/viewing-fathers-attachment-f%E2%80%8A%E2%80%8A%E2%80%8Aigures/|url-status=live|website=Counseling today|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170924022707/http://ct.counseling.org:80/2017/09/viewing-fathers-attachment-f%E2%80%8A%E2%80%8A%E2%80%8Aigures/ |archive-date=2017-09-24 }}</ref> A secure attachment to a father who is a "secondary attachment figure" may also counter the possible negative effects of an unsatisfactory attachment to a mother who is the primary attachment figure.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lamb |first1=Michael E. |last2=Lamb |first2=Jamie E. |date=1976 |title=The Nature and Importance of the Father-Infant Relationship |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/582850 |journal=The Family Coordinator |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=379–385 |doi=10.2307/582850 |jstor=582850 |issn=0014-7214}}</ref> | ||

| Some infants direct attachment behaviour (proximity seeking) towards more than one attachment figure almost as soon as they start to show discrimination between caregivers; most come to do so during their second year. These figures are arranged hierarchically, with the principal attachment figure at the top.<ref>Bowlby (1969) 2nd ed. pp. 304–05.</ref> The set-goal of the attachment behavioural system is to maintain a bond with an accessible and available attachment figure.<ref name=kobmad>{{cite encyclopedia|author= Kobak R, Madsen S|year=2008|title= Disruption in Attachment Bonds|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| |

Some infants direct attachment behaviour (proximity seeking) towards more than one attachment figure almost as soon as they start to show discrimination between caregivers; most come to do so during their second year. These figures are arranged hierarchically, with the principal attachment figure at the top.<ref>Bowlby (1969) 2nd ed. pp. 304–05.</ref> The set-goal of the attachment behavioural system is to maintain a bond with an accessible and available attachment figure.<ref name=kobmad>{{cite encyclopedia|author= Kobak R, Madsen S|year=2008|title= Disruption in Attachment Bonds|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| veditors = Cassidy J, Shaver PR | publisher= Guilford Press|location= New York and London|pages=23–47|isbn=978-1-59385-874-2}}</ref> "Alarm" is the term used for activation of the attachment behavioural system caused by fear of danger. "Anxiety" is the anticipation or fear of being cut off from the attachment figure. If the figure is unavailable or unresponsive, separation distress occurs.<ref name="pg16">] p. 16.</ref> In infants, physical separation can cause anxiety and anger, followed by sadness and despair. By age three or four, physical separation is no longer such a threat to the child's bond with the attachment figure. Threats to security in older children and adults arise from prolonged absence, breakdowns in communication, emotional unavailability or signs of rejection or abandonment.<ref name=kobmad/> | ||

| ===Behaviours=== | ===Behaviours=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The attachment behavioural system serves to maintain or achieve closer proximity to the attachment figure.<ref>] p. 17.</ref> Pre-attachment behaviours occur in the first six months of life. During the first phase (the first eight weeks), infants smile, babble and cry to attract the attention of caregivers. Although infants of this age learn to discriminate between caregivers, these behaviours are directed at anyone in the vicinity. During the second phase (two to six months), the infant increasingly discriminates between familiar and unfamiliar adults, becoming more responsive towards the caregiver; following and clinging are added to the range of behaviours. Clear-cut attachment develops in the third phase, between the ages of six months and two years. The infant's behaviour towards the caregiver becomes organised on a goal-directed basis to achieve the conditions that make it feel secure.<ref name="Prior and Glaser p. 19">] p. 19.</ref> By the end of the first year, the infant is able to display a range of attachment behaviours designed to maintain proximity. These manifest as protesting the caregiver's departure, greeting the caregiver's return, clinging when frightened and following when able.<ref>] pp. 90–92.</ref> With the development of locomotion, the infant begins to use the caregiver or caregivers as a safe base from which to explore.<ref name="Prior and Glaser p. 19"/> Infant exploration is greater when the caregiver is present because the infant's attachment system is relaxed and it is free to explore. If the caregiver is inaccessible or unresponsive, attachment behaviour is more strongly exhibited.<ref name="ainsworth 67">{{cite book|author=Ainsworth M |title=Infancy in Uganda: Infant Care and the Growth of Love|year=1967|isbn=0-8018-0010-2 |location=Baltimore |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press}}</ref> Anxiety, fear, illness and fatigue will cause a child to increase attachment behaviours.<ref>] p. 97.</ref> | |||

| The attachment behavioural system serves to achieve or maintain proximity to the attachment figure.{{sfn|Prior|Glaser|2006|p=17}} | |||

| After the second year, as the child begins to see the carer as an independent person, a more complex and goal-corrected partnership is formed.<ref>] pp. 19–20.</ref> Children begin to notice others' goals and feelings and plan their actions accordingly. For example, whereas babies cry because of pain, two-year-olds cry to summon their caregiver, and if that does not work, cry louder, shout or follow.<ref name="Schaffer"/> | |||

| Pre-attachment behaviours occur in the first six months of life. During the first phase (the first two months), infants smile, babble, and cry to attract the attention of potential caregivers. Although infants of this age learn to discriminate between caregivers, these behaviours are directed at anyone in the vicinity. | |||

| During the second phase (two to six months), the infant discriminates between familiar and unfamiliar adults, becoming more responsive toward the caregiver; following and clinging are added to the range of behaviours. The infant's behaviour toward the caregiver becomes organized on a goal-directed basis to achieve the conditions that make it feel secure.{{sfn|Prior|Glaser|2006|p=19}} | |||

| By the end of the first year, the infant is able to display a range of attachment behaviours designed to maintain proximity. These manifest as protesting the caregiver's departure, greeting the caregiver's return, clinging when frightened, and following when able.{{sfn|Karen|1998|pp=90–92}} | |||

| With the development of locomotion, the infant begins to use the caregiver or caregivers as a "safe base" from which to explore.{{sfn|Prior|Glaser|2006|p=19}}<ref>{{cite book |title=Disorders of childhood : development and psychopathology | first1 = Robin Hornik | last1 = Parritz | first2 = Michael F | last2 = Troy |date=2017-05-24 |isbn=978-1-337-09811-3 |edition=Third |location=Boston, MA |oclc=960031712}}</ref>{{Rp|71}} Infant exploration is greater when the caregiver is present because the infant's attachment system is relaxed and it is free to explore. If the caregiver is inaccessible or unresponsive, attachment behaviour is more strongly exhibited.<ref name="ainsworth 67">{{cite book |title=Infancy in Uganda: Infant Care and the Growth of Love | vauthors = Ainsworth M |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press |year=1967 |isbn=978-0-8018-0010-8 |location=Baltimore}}</ref> Anxiety, fear, illness, and fatigue will cause a child to increase attachment behaviours.{{sfn|Karen|1998|p=97}} | |||

| After the second year, as the child begins to see the caregiver as an independent person, a more complex and goal-corrected partnership is formed.{{sfn|Prior|Glaser|2006|pp=19–20}} Children begin to notice others' goals and feelings and plan their actions accordingly. | |||

| {{for-text|coverage of this topic in ]|]}} | |||

| ===Tenets=== | ===Tenets=== | ||

| Modern attachment theory is based on three principles:<ref name=":9">{{cite book |title=Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) with Individuals, Couples and Families |last=Johnson |first=Susan M. |publisher=The Guildford Press |year=2019 |isbn=978-1-4625-3828-7 |location=New York |pages=5}}</ref> | |||

| Common human attachment behaviours and emotions are ]. Human evolution has involved selection for social behaviours that make individual or group survival more likely. The commonly observed attachment behaviour of toddlers staying near familiar people would have had safety advantages in the environment of early adaptation, and has such advantages today. Bowlby saw the environment of early adaptation as similar to current ] societies.<ref>Bowlby (1969) p. 300.</ref> There is a survival advantage in the capacity to sense possibly dangerous conditions such as unfamiliarity, being alone or rapid approach. According to Bowlby, proximity-seeking to the attachment figure in the face of threat is the "set-goal" of the attachment behavioural system.<ref name="pg16"/> | |||

| # Bonding is an intrinsic human need. | |||

| # Regulation of emotion and fear to enhance vitality. | |||

| # Promoting adaptiveness and growth. | |||

| Common attachment behaviours and emotions, displayed in most social primates including humans, are ]. The long-term evolution of these species has involved selection for social behaviours that make individual or group survival more likely. The commonly observed attachment behaviour of toddlers staying near familiar people would have had safety advantages in the environment of early adaptation and has similar advantages today. Bowlby saw the environment of early adaptation as similar to current ] societies.{{sfn|Bowlby|1971|p=300}} There is a survival advantage in the capacity to sense possibly dangerous conditions such as unfamiliarity, being alone, or rapid approach. According to Bowlby, proximity-seeking to the attachment figure in the face of threat is the "set-goal" of the attachment behavioural system.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bowlby|first=John|url=https://mindsplain.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ATTACHMENT_AND_LOSS_VOLUME_I_ATTACHMENT.pdf|title=Attachment and loss|publisher=]|year=1969–1982|pages=11|language=English}}</ref> | |||

| Bowlby's original account of a ] during which attachments can form of between six months and two to three years has been modified by later researchers. These researchers have shown there is indeed a sensitive period during which attachments will form if possible, but the time frame is broader and the effect less fixed and irreversible than first proposed.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McLeod|first=Dr. Saul|date=5 February 2017|title=Bowlby's Attachment Theory|url=https://www.simplypsychology.org/bowlby.html|website=]}}</ref> | |||

| The attachment system is very robust and young humans form attachments easily, even in far less than ideal circumstances.<ref name="Bowlby 58">{{cite journal|author = Bowlby J|title = The nature of the child's tie to his mother|journal = International Journal of Psychoanalysis|volume = 39|issue = 5|pages = 350–73|year = 1958|pmid = 13610508}}</ref> In spite of this robustness, significant separation from a familiar caregiver—or frequent changes of caregiver that prevent the development of attachment—may result in psychopathology at some point in later life.<ref name="Bowlby 58"/> Infants in their first months have no preference for their biological parents over strangers. Preferences for certain people, plus behaviours which solicit their attention and care, are developed over a considerable period of time.<ref name="Bowlby 58"/> When an infant is upset by separation from their caregiver, this indicates that the bond no longer depends on the presence of the caregiver, but is of an enduring nature.<ref name="Schaffer"/> ] | |||

| With further research, authors discussing attachment theory have come to appreciate social development is affected by later as well as earlier relationships. Early steps in attachment take place most easily if the infant has one caregiver, or the occasional care of a small number of other people. According to Bowlby, almost from the beginning, many children have more than one figure toward whom they direct attachment behaviour. These figures are not treated alike; there is a strong bias for a child to direct attachment behaviour mainly toward one particular person. Bowlby used the term "monotropy" to describe this bias.{{sfn|Bowlby|1982|p=309}} Researchers and theorists have abandoned this concept insofar as it may be taken to mean the relationship with the special figure differs ''qualitatively'' from that of other figures. Rather, current thinking postulates definite hierarchies of relationships.<ref name="Rutter 95">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rutter M | title = Clinical implications of attachment concepts: retrospect and prospect | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_journal-of-child-psychology-and-psychiatry-and-allied-disciplines_1995-05_36_4/page/549 | journal = Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines | volume = 36 | issue = 4 | pages = 549–71 | date = May 1995 | pmid = 7650083 | doi = 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02314.x }}</ref><ref name="Main">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1999 |title=Epilogue: Attachment Theory: Eighteen Points with Suggestions for Future Studies |encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications |publisher=Guilford Press |location=New York |url= https://archive.org/details/handbookofattach0000unse/page/845 |pages= |isbn=978-1-57230-087-3 |quote=although there is general agreement an infant or adult will have only a few attachment figures at most, many attachment theorists and researchers believe infants form 'attachment hierarchies' in which some figures are primary, others secondary, and so on. This position can be presented in a stronger form, in which a particular figure is believed continually to take top place ("monotropy") ... questions surrounding monotropy and attachment hierarchies remain unsettled |author=Main M |veditors=Cassidy J, Shaver PR}}</ref> | |||

| Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviours about the self and others. This system, called the "internal working model of social relationships", continues to develop with time and experience.{{sfn|Mercer|2006|pp=39–40}} | |||

| Early experiences with caregivers gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviours about the self and others. This system, called the "internal working model of social relationships", continues to develop with time and experience.<ref name="Mercer pp.39–40">] pp.39–40.</ref> Internal models regulate, interpret and predict attachment-related behaviour in the self and the attachment figure. As they develop in line with environmental and developmental changes, they incorporate the capacity to reflect and communicate about past and future attachment relationships.<ref name="Bretherton/Mul"/> They enable the child to handle new types of social interactions; knowing, for example, that an infant should be treated differently from an older child, or that interactions with teachers and parents share characteristics. This internal working model continues to develop through adulthood, helping cope with friendships, marriage and parenthood, all of which involve different behaviours and feelings.<ref name="Mercer pp.39–40"/><ref name="Bowlby 73">{{cite book|author= Bowlby J|year=1973|title=Separation: Anger and Anxiety|series= Attachment and loss. Vol. 2 |location=London| publisher=Hogarth |isbn=0-7126-6621-4}}</ref> The development of attachment is a transactional process. Specific attachment behaviours begin with predictable, apparently innate, behaviours in infancy. They change with age in ways that are determined partly by experiences and partly by situational factors.<ref>Bowlby (1969) pp. 414–21.</ref> As attachment behaviours change with age, they do so in ways shaped by relationships. A child's behaviour when reunited with a caregiver is determined not only by how the caregiver has treated the child before, but on the history of effects the child has had on the caregiver.<ref>Bowlby (1969) pp. 394–395.</ref><ref name="ainsworth 69">{{cite journal|author = Ainsworth MD|title = Object relations, dependency, and attachment: a theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship|journal = Child Development|volume = 40|issue = 4|pages = 969–1025|year = 1969|month = December|pmid = 5360395|doi = 10.2307/1127008|publisher = Blackwell Publishing| jstor =1127008}}</ref> | |||

| Internal models regulate, interpret, and predict attachment-related behaviour in the self and the attachment figure. As they develop in line with environmental and developmental changes, they incorporate the capacity to reflect and communicate about past and future attachment relationships.<ref name="Bretherton/Mul"/> They enable the child to handle new types of social interactions; knowing, for example, an infant should be treated differently from an older child, or that interactions with teachers and parents share characteristics. Even interaction with coaches share similar characteristics, as athletes who secure attachment relationships with not only their parents but their coaches will play a role in the growth of athletes in their prospective sport.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Davis |first1=Louise |last2=Brown |first2=Daniel J. |last3=Arnold |first3=Rachel |last4=Gustafsson |first4=Henrik |date=2021-08-02 |title=Thriving Through Relationships in Sport: The Role of the Parent–Athlete and Coach–Athlete Attachment Relationship |journal=Frontiers in Psychology |volume=12 |pages=694599 |doi=10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694599 |issn=1664-1078 |pmc=8366224 |pmid=34408711|doi-access=free }}</ref> This internal working model continues to develop through adulthood, helping cope with friendships, marriage, and parenthood, all of which involve different behaviours and feelings.<ref name="Bowlby 73">{{cite book |title=Separation: Anger and Anxiety | vauthors = Bowlby J |publisher=Hogarth |year=1973 |isbn=978-0-7126-6621-3 |series=Attachment and loss. Vol. 2 |location=London}}</ref>{{sfn|Mercer|2006|pp=39–40}} | |||

| ==Changes in attachment during childhood and adolescence== | |||

| Age, cognitive growth and continued social experience advance the development and complexity of the internal working model. Attachment-related behaviours lose some characteristics typical of the infant-toddler period and take on age-related tendencies. The preschool period involves the use of negotiation and bargaining.<ref name= "Waters">{{cite journal|author=Waters E, Kondo-Ikemura K, Posada G, Richters J|year=1991|contribution=Learning to love: Mechanisms and milestones|title= Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology|volume= 23|issue=Self–Processes and Development|editor=Gunnar M, Sroufe T|location= Hillsdale, NJ|publisher=Erlbaum}}</ref> For example, four-year-olds are not distressed by separation if they and their caregiver have already negotiated a shared plan for the separation and reunion.<ref name=marbrit>{{cite encyclopedia|author= Marvin RS, Britner PA|year=2008|title= Normative Development: The Ontogeny of Attachment|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| editors= Cassidy J, Shaver PR| publisher= Guilford Press|location= New York and London|pages=269–94|isbn=9781593858742}}</ref>] | |||

| The development of attachment is a transactional process. Specific attachment behaviours begin with predictable, apparently innate, behaviours in infancy.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Pilkington |first1=Pamela D. |last2=Bishop |first2=Amy |last3=Younan |first3=Rita |date=2021 |title=Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cpp.2533 |journal=Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy |language=en |volume=28 |issue=3 |pages=569–584 |doi=10.1002/cpp.2533 |pmid=33270299 |s2cid=227258822 |issn=1063-3995}}</ref> They change with age in ways determined partly by experiences and partly by situational factors.{{sfn|Bowlby|1971|pp=414–21}} As attachment behaviours change with age, they do so in ways shaped by relationships. A child's behaviour when reunited with a caregiver is determined not only by how the caregiver has treated the child before, but on the history of effects the child has had on the caregiver.{{sfn|Bowlby|1971|pp=394–395}}<ref name="ainsworth 69">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ainsworth MD | title = Object relations, dependency, and attachment: a theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_child-development_1969-12_40_4/page/969 | journal = Child Development | volume = 40 | issue = 4 | pages = 969–1025 | date = December 1969 | pmid = 5360395 | doi = 10.2307/1127008 | jstor = 1127008 }}</ref> | |||

| === Cultural differences === | |||

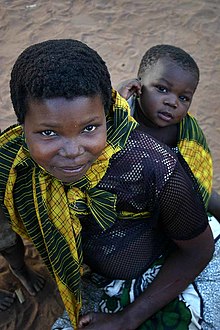

| In Western culture child-rearing, there is a focus on single attachment to primarily the mother. This dyadic model is not the only strategy of attachment producing a secure and emotionally adept child. Having a single, dependably responsive and sensitive caregiver (namely the mother) does not guarantee the ultimate success of the child. Results from Israeli, Dutch and east African studies show children with multiple caregivers grow up not only feeling secure, but developed "more enhanced capacities to view the world from multiple perspectives."<ref name=":12">{{cite book |title=Mothers and Others-The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding |url=https://archive.org/details/mothersothersevo0000hrdy |last=Hrdy |first=Sarah Blaffer |publisher=The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-674-03299-6 |location=United States of America |pages=, 131, 132}}</ref> This evidence can be more readily found in hunter-gatherer communities, like those that exist in rural Tanzania.<ref>{{Citation|last1=Crittenden|first1=Alyssa N.|title=Cooperative Child Care among the Hadza: Situating Multiple Attachment in Evolutionary Context|date=2013|work=Attachment Reconsidered|pages=67–83|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US|isbn=978-1-137-38674-8|last2=Marlowe|first2=Frank W.|doi=10.1057/9781137386724_3}}</ref> | |||

| In hunter-gatherer communities, in the past and present, mothers are the primary caregivers, but share the maternal responsibility of ensuring the child's survival with a variety of different ]. So while the mother is important, she is not the only opportunity for relational attachment a child can make. Several group members (with or without blood relation) contribute to the task of bringing up a child, sharing the parenting role and therefore can be sources of multiple attachment. There is evidence of this communal parenting throughout history that "would have significant implications for the evolution of multiple attachment."<ref>{{cite book |title=Attachment Reconsidered: Cultural Perspectives on a Western Theory |last1=Quinn |first1=Naomi |last2=Mageo |first2=Jeannette Marie |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-137-38672-4 |location=United States of America |pages=73, 74}}</ref> | |||

| Ideally, these social skills become incorporated into the internal working model to be used with other children and later with adult peers. As children move into the school years at about six years old, most develop a goal-corrected partnership with parents, in which each partner is willing to compromise in order to maintain a gratifying relationship.<ref name= "Waters"/> By middle childhood, the goal of the attachment behavioural system has changed from proximity to the attachment figure to availability. Generally, a child is content with longer separations, provided contact—or the possibility of physically reuniting, if needed—is available. Attachment behaviours such as clinging and following decline and self-reliance increases.<ref name=kerns/> By middle childhood (ages 7–11), there may be a shift towards mutual ] of secure-base contact in which caregiver and child negotiate methods of maintaining communication and supervision as the child moves towards a greater degree of independence.<ref name= "Waters"/> | |||

| In "non-metropolis" India {{clarify span|text=(where "dual income nuclear families" are more the norm and dyadic mother relationship is)| | |||

| In early childhood, parental figures remain the centre of a child's social world, even if they spend substantial periods of time in alternative care. This gradually lessens, particularly during the child's entrance into formal schooling.<ref name=kerns/> The attachment models of young children are typically assessed in relation to particular figures, such as parents or other caregivers. There appear to be limitations in their thinking that restrict their ability to integrate relationship experiences into a single general model. Children usually begin to develop a single general model of attachment relationships during ], although this may occur in middle childhood.<ref name=kerns>{{cite encyclopedia|author= Kerns KA|year=2008|title= Attachment in Middle Childhood|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| editors= Cassidy J, Shaver PR| publisher= Guilford Press|location= New York and London|pages=366–82|isbn=9781593858742}}</ref> | |||

| explain=dyadic mother relationship is... what? is "and" supposed to be "than"?|date=July 2023}}, where a family normally consists of 3 generations (and sometimes 4: great-grandparents, grandparents, parents, and child or children), the child or children would have four to six caregivers from whom to select their "attachment figure". A child's "uncles and aunts" (parents' siblings and their spouses) also contribute to the child's psycho-social enrichment.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Parens |first=Henri |date=1995 |title=Parenting for Emotional Growth: Lines of Development |url=https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1003&context=parentingemotionalgrowth |access-date=March 14, 2024 |website=Thomas Jefferson University-Jefferson Digital Commons}}</ref> | |||

| Although it has been debated for years, and there are differences across cultures, research has shown that the three basic aspects of attachment theory are, to some degree, universal.<ref name="IJzendoorn MH 2008. pp. 880">{{cite book | vauthors = Van Ijzendoorn MH, Sagi-Schwartz A | chapter = Cross-cultural patterns of attachment: Universal and contextual dimensions. | veditors = Cassidy J, Shaver PR | title = Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. | url = https://archive.org/details/handbookofattach0000unse_n9k8 | edition = 2nd | location = New York, NY | publisher = Guilford Press | date = 2008 | pages = –905 }}</ref> Studies in Israel and Japan resulted in findings which diverge from a number of studies completed in Western Europe and the United States. The prevailing hypotheses are: 1) that secure attachment is the most desirable state, and the most prevalent; 2) maternal sensitivity influences infant attachment patterns; and 3) specific infant attachments predict later social and cognitive competence.<ref name="IJzendoorn MH 2008. pp. 880" /> | |||

| Relationships with peers have an influence on the child that is distinct from that of parent-child relationships, though the latter can influence the peer relationships children form.<ref name="Schaffer"/> Although peers become important in middle childhood, the evidence suggests peers do not become attachment figures, though children may direct attachment behaviours at peers if parental figures are unavailable. Attachments to peers tend to emerge in adolescence, although parents continue to be attachment figures.<ref name=kerns/> With adolescents, the role of the parental figures is to be available when needed while the adolescent makes excursions into the outside world.<ref>Bowlby (1988) p. 11.</ref> | |||

| ==Attachment patterns== | ==Attachment patterns== | ||

| {{See also|Attachment in children|Attachment measures}} | |||

| Much of attachment theory was informed by ]'s innovative methodology and observational studies, particularly those undertaken in Scotland and Uganda. Ainsworth's work expanded the theory's concepts and enabled empirical testing of its tenets.<ref name="Bretherton"/> Using Bowlby's early formulation, she conducted observational research on infant-parent pairs (or ]) during the child's first year, combining extensive home visits with the study of behaviours in particular situations. This early research was published in 1967 in a book titled ''Infancy in Uganda''.<ref name="Bretherton"/> Ainsworth identified three attachment styles, or patterns, that a child may have with attachment figures: secure, anxious-avoidant (insecure) and anxious-ambivalent or resistant (insecure). She devised a procedure known as the ] as the laboratory portion of her larger study, to assess separation and reunion behaviour.<ref name="Ainsworth,1978a">{{cite book|author=Ainsworth MD, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S |year=1978|title=Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation|publisher= Lawrence Erlbaum Associates|location =Hillsdale NJ|isbn=0-89859-461-8}}</ref> This is a standardised research tool used to assess attachment patterns in infants and toddlers. By creating stresses designed to activate attachment behaviour, the procedure reveals how very young children use their caregiver as a source of security.<ref name="Schaffer"/> Carer and child are placed in an unfamiliar playroom while a researcher records specific behaviours, observing through a ]. In eight different episodes, the child experiences separation from/reunion with the carer and the presence of an unfamiliar stranger.<ref name="Ainsworth,1978a"/> | |||

| {{blockquote|The strength of a child's attachment behaviour in a given circumstance does not indicate the "strength" of the attachment bond. Some insecure children will routinely display very pronounced attachment behaviours, while many secure children find that there is no great need to engage in either intense or frequent shows of attachment behaviour.<ref>Howe, D. (2011) Attachment across the lifecourse, London: Palgrave, p.13</ref>}} | |||

| Ainsworth's work in the United States attracted many scholars into the field, inspiring research and challenging the dominance of ].<ref>] pp. 163–73.</ref> Further research by ] and colleagues at the ] identified a fourth attachment pattern, called disorganized/disoriented attachment. The name reflects these children's lack of a coherent coping strategy.<ref name="Main & Solomon">{{cite encyclopedia|author= Main M, Solomon J|year=1986 |title=Discovery of an insecure disoriented attachment pattern: procedures, findings and implications for the classification of behavior|encyclopedia= Affective Development in Infancy|editors=Brazelton T, Youngman M|isbn=0893913456|location= Norwood, NJ |publisher= Ablex}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|Individuals with different attachment styles have different beliefs about romantic love period, availability, trust capability of love partners and love readiness.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Honari B, Saremi AA | year = 2015 | title = The Study of Relationship between Attachment Styles and Obsessive Love Style | journal = Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences | volume = 165 | pages = 152–159 | doi = 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.617 | doi-access = free }}</ref>}} | |||

| ===Secure attachment=== | |||

| The type of attachment developed by infants depends on the quality of care they have received.<ref name=PPP/> Each of the attachment patterns is associated with certain characteristic patterns of behaviour, as described in the following table: | |||

| {{Main|Secure attachment}} | |||

| A toddler who is securely attached to his or her parent (or other familiar caregiver) will explore freely while the caregiver is present, typically engages with strangers, is often visibly upset when the caregiver departs, and is generally happy to see the caregiver return. The extent of exploration and of distress are affected, however, by the child's temperamental make-up and by situational factors as well as by attachment status. A child's attachment is largely influenced by their primary caregiver's sensitivity to their needs. Parents who consistently (or almost always) respond to their child's needs will create securely attached children. Such children are certain that their parents will be responsive to their needs and communications.<ref>] et al. (2009). Psychology, Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers. pp.441</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style = "float:right; margin-left:15px; text-align:left; font-size:95%;" | |||

| |+ ''' Child and caregiver behaviour patterns before the age of 18 months'''<ref name="Ainsworth,1978a"/><ref name="Main & Solomon"/> | |||

| In the traditional Ainsworth et al. (1978) coding of the ], secure infants are denoted as "Group B" infants and they are further subclassified as B1, B2, B3, and B4.<ref name="Ainsworth, M.D.S, Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S.">{{cite book | vauthors = Ainsworth MD, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S | date = 1978 | title = Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. | location = Hillsdale, NJ | publisher = Earlbaum }}</ref> Although these subgroupings refer to different stylistic responses to the comings and goings of the caregiver, they were not given specific labels by Ainsworth and colleagues, although their descriptive behaviours led others (including students of Ainsworth) to devise a relatively "loose" terminology for these subgroups. B1's have been referred to as "secure-reserved", B2's as "secure-inhibited", B3's as "secure-balanced", and B4's as "secure-reactive". However, in academic publications the classification of infants (if subgroups are denoted) is typically simply "B1" or "B2", although more theoretical and review-oriented papers surrounding attachment theory may use the above terminology. Secure attachment is the most common type of attachment relationship seen throughout societies.<ref name="Ainsworth,1978a" /> | |||

| ! Attachment<br /> pattern | |||

| !width="55%" |Child | |||

| !width="35%" |Caregiver | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| ! Secure | |||

| |align="left"|Uses caregiver as a secure base for exploration. Protests caregiver's departure and seeks proximity and is comforted on return, returning to exploration. May be comforted by the stranger but shows clear preference for the caregiver.|| Responds appropriately, promptly and consistently to needs. Caregiver has successfully formed a secure parental attachment bond to the child. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| ! Avoidant | |||

| |align="left"|Little affective sharing in play. Little or no distress on departure, little or no visible response to return, ignoring or turning away with no effort to maintain contact if picked up. Treats the stranger similarly to the caregiver. The child feels that there is no attachment; therefore, the child is rebellious and has a lower self-image and self-esteem. || Little or no response to distressed child. Discourages crying and encourages independence. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| !Ambivalent/Resistant | |||

| |align="left"|Unable to use caregiver as a secure base, seeking proximity before separation occurs. Distressed on separation with ambivalence, anger, reluctance to warm to caregiver and return to play on return. Preoccupied with caregiver's availability, seeking contact but resisting angrily when it is achieved. Not easily calmed by stranger. In this relationship, the child always feels anxious because the caregiver's availability is never consistent. || Inconsistent between appropriate and neglectful responses. Generally will only respond after increased attachment behavior from the infant. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| !Disorganized | |||

| |align="left"| ] on return such as freezing or rocking. Lack of coherent attachment strategy shown by contradictory, disoriented behaviours such as approaching but with the back turned. || Frightened or frightening behaviour, intrusiveness, withdrawal, negativity, role confusion, affective communication errors and maltreatment. Very often associated with many forms of abuse towards the child. | |||

| |} | |||

| Securely attached children are best able to explore when they have the knowledge of a secure base (their caregiver) to return to in times of need. When assistance is given, this bolsters the sense of security and also, assuming the parent's assistance is helpful, educates the child on how to cope with the same problem in the future. Therefore, secure attachment can be seen as the most adaptive attachment style. According to some psychological researchers, a child becomes securely attached when the parent is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner. At infancy and early childhood, if parents are caring and attentive towards their children, those children will be more prone to secure attachment.<ref name="Aronoff, J. 2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Aronoff J |year=2012 |title=Parental Nurturance in the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample: Theory, Coding, and Scores | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_cross-cultural-research_2012-11_46_4/page/315 |journal=Cross-Cultural Research |volume=46 |issue=4 |pages=315–347 |doi=10.1177/1069397112450851|s2cid=147304847 }}</ref> | |||

| The presence of an attachment is distinct from its quality. Infants form attachments if there is someone to interact with, even if mistreated. Individual differences in the relationships reflect the history of care, as infants begin to predict the behaviour of caregivers through repeated interactions.<ref name=wsec/> The focus is the organisation (pattern) rather than quantity of attachment behaviours. Insecure attachment patterns are non-optimal as they can compromise exploration, self-confidence and mastery of the environment. However, insecure patterns are also adaptive, as they are suitable responses to caregiver unresponsiveness. For example, in the avoidant pattern, minimising expressions of attachment even in conditions of mild threat may forestall alienating caregivers who are already rejecting, thus leaving open the possibility of responsiveness should a more serious threat arise.<ref name=wsec>{{cite encyclopedia|author= Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E|year=2008|title= Individual Differences in Infant-Caregiver Attachment|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| editors= Cassidy J, Shaver PR| publisher= Guilford Press|location= New York and London|pages=78–101|isbn=9781593858742}}</ref> | |||

| ===Anxious-ambivalent attachment=== | |||

| Around 65% of children in the general population may be classified as having a secure pattern of attachment, with the remaining 35% being divided between the insecure classifications.<ref name=pg31>] pp. 30–31.</ref> Recent research has sought to ascertain the extent to which a parent's attachment classification is predictive of their children's classification. Parents' perceptions of their own childhood attachments were found to predict their children's classifications 75% of the time.<ref name="main 85">{{cite encyclopedia|author=Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J|year=1985|title=Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation|editors=Bretherton I, Waters E|encyclopedia=Growing Points of Attachment Theory and Research|location=Chicago|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=9780226074115}}</ref><ref name="fonagy 91">{{cite journal|author=Fonagy P, Steele M, Steele H|title=Maternal representations of attachment predict the organisation of infant mother–attachment at one year of age|journal=Child Development|volume=62|pages=891–905|doi=10.2307/1131141|year=1991|pmid=1756665|issue=5|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|jstor=1131141}}</ref><ref name="steele">{{cite journal|author=Steele H, Steele M, Fonagy P|year=1996|journal=Child Development|title=Associations among attachment classifications of mothers, fathers, and their infants|volume=67|pages=541–55|doi=10.2307/1131831|pmid=8625727|issue=2|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|jstor=1131831}}</ref> | |||

| Anxious-ambivalent attachment is a form of insecure attachment and is also misnamed as "resistant attachment".<ref name="Ainsworth,1978a">{{cite book |title=Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation |vauthors=Ainsworth MD, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S |publisher=Lawrence Erlbaum Associates |year=1978 |isbn=978-0-89859-461-4 |location=Hillsdale NJ}}</ref><ref name="Plotka 2011 pp. 81–83">{{cite book | last=Plotka | first=Raquel | title=Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development | chapter=Ambivalent Attachment | publisher=Springer US | publication-place=Boston, MA | year=2011 | doi=10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_104 | pages=81–83| isbn=978-0-387-77579-1 |quote=Ambivalent attachment is a form of insecure attachment characterized by inconsistent responses of the caregivers and by the child's feelings of anxiety and preoccupation about the caregiver's availability.}}</ref> In general, a child with an anxious-ambivalent pattern of attachment will typically explore little (in the Strange Situation) and is often wary of strangers, even when the parent is present. When the caregiver departs, the child is often highly distressed showing behaviours such as crying or screaming. The child is generally ambivalent when the caregiver returns.<ref name="Ainsworth, M.D.S, Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S." /> The anxious-ambivalent strategy is a response to unpredictably responsive caregiving, and the displays of anger (ambivalent resistant, C1) or helplessness (ambivalent passive, C2) towards the caregiver on reunion can be regarded as a conditional strategy for maintaining the availability of the caregiver by preemptively taking control of the interaction.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Solomon J, George C, De Jong A |year=1995 |title=Children classified as controlling at age six: Evidence of disorganized representational strategies and aggression at home and at school |journal=Development and Psychopathology |volume=7 |issue=3 |pages=447–463 |doi=10.1017/s0954579400006623|s2cid=146576663 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Crittenden P | date = 1999 | chapter = Danger and development: the organization of self-protective strategies | title = Atypical Attachment in Infancy and Early Childhood Among Children at Developmental Risk | url = https://archive.org/details/atypicalattachme0000unse | veditors = Vondra JI, Barnett D | location = Oxford | publisher = Blackwell | pages = –171 | isbn = 978-0-631-21592-9 }}</ref> | |||

| The C1 (ambivalent resistant) subtype is coded when "resistant behavior is particularly conspicuous. The mixture of seeking and yet resisting contact and interaction has an unmistakably angry quality and indeed an angry tone may characterize behavior in the preseparation episodes".<ref name="Ainsworth, M.D.S, Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S." /> | |||

| Over the short term, the stability of attachment classifications is high, but becomes less so over the long term.<ref name="Schaffer"/> It appears that stability of classification is linked to stability in caregiving conditions. Social stressors or negative life events—such as illness, death, abuse or divorce—are associated with instability of attachment patterns from infancy to early adulthood, particularly from secure to insecure.<ref name=delguid/> Conversely, these difficulties sometimes reflect particular upheavals in people's lives, which may change. Sometimes, parents' responses change as the child develops, changing classification from insecure to secure. Fundamental changes can and do take place after the critical early period.<ref name="Karen pp. 248–66">] pp. 248–66.</ref> Physically abused and neglected children are less likely to develop secure attachments, and their insecure classifications tend to persist through the pre-school years. Neglect alone is associated with insecure attachment organisations, and rates of disorganized attachment are markedly elevated in maltreated infants.<ref name=PPP/> | |||

| Regarding the C2 (ambivalent passive) subtype, Ainsworth et al. wrote: | |||

| This situation is complicated by difficulties in ] classification in older age groups. The Strange Situation procedure is for ages 12 to 18 months only;<ref name="Schaffer"/> adapted versions exist for pre-school children.<ref name=AACAP-2005/> Techniques have been developed to allow verbal ascertainment of the child's state of mind with respect to attachment. An example is the "stem story", in which a child is given the beginning of a story that raises attachment issues and asked to complete it. For older children, adolescents and adults, semi-structured interviews are used in which the manner of relaying content may be as significant as the content itself.<ref name="Schaffer"/> However, there are no substantially validated measures of attachment for middle childhood or early adolescence (approximately 7 to 13 years of age).<ref name=AACAP-2005>{{cite journal |journal= J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry |year=2005 |volume=44 |issue=11 |pages=1206–19 |title= Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder of infancy and early childhood |author= Boris NW, Zeanah CH, Work Group on Quality Issues |pmid=16239871 |url=http://www.aacap.org/galleries/PracticeParameters/rad.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=September 13, 2009 |doi= 10.1097/01.chi.0000177056.41655.ce}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|Perhaps the most conspicuous characteristic of C2 infants is their passivity. Their exploratory behavior is limited throughout the SS and their interactive behaviors are relatively lacking in active initiation. Nevertheless, in the reunion episodes they obviously want proximity to and contact with their mothers, even though they tend to use signalling rather than active approach, and protest against being put down rather than actively resisting release ... In general the C2 baby is not as conspicuously angry as the C1 baby.<ref name="Ainsworth, M.D.S, Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S." />}} | |||

| Some authors have questioned the idea that a ] of categories representing a qualitative difference in attachment relationships can be developed. Examination of data from 1,139 15-month-olds showed that variation in attachment patterns was continuous rather than grouped.<ref name="FraSpe">{{cite journal|author = Fraley RC, Spieker SJ|title = Are infant attachment patterns continuously or categorically distributed? A taxometric analysis of strange situation behavior|journal = Developmental Psychology|volume = 39|issue = 3|pages = 387–404|year = 2003|month = May|pmid = 12760508|doi = 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.387}}</ref> This criticism introduces important questions for attachment typologies and the mechanisms behind apparent types. However, it has relatively little relevance for attachment theory itself, which "neither requires nor predicts discrete patterns of attachment".<ref name="WatBea">{{cite journal|author = Waters E, Beauchaine TP|title = Are there really patterns of attachment? Comment on Fraley and Spieker (2003)|journal = Developmental Psychology|volume = 39|issue = 3|pages = 417–22; discussion 423–9|year = 2003|month = May|pmid = 12760512 |doi = 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.417}}</ref> | |||

| Research done by McCarthy and Taylor (1999) found that children with ] were more likely to develop ambivalent attachments. The study also found that children with ambivalent attachments were more likely to experience difficulties in maintaining intimate relationships as adults.<ref name="mccarthy1999avoidant">{{cite news |title=Avoidant/ambivalent attachment style as a mediator between abusive childhood experiences and adult relationship difficulties |url=https://archive.org/details/sim_journal-of-child-psychology-and-psychiatry_1999-03_40_3/page/465 |last1=McCarthy |first1=Gerard |last2=Taylor |first2=Alan |work=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry |year=1999 |issue=3 |volume=40 |pages=465–477 |doi=10.1111/1469-7610.00463 |ref=mccarthy1999avoidant}}</ref> | |||

| ===Significance of attachment patterns=== | |||

| There is an extensive body of research demonstrating a significant association between attachment organisations and children's functioning across multiple domains.<ref name=PPP>{{cite book|author=Pearce JW, Pezzot-Pearce TD|title=Psychotherapy of abused and neglected children|publisher=Guilford press|edition=2nd|location=New York and London|year=2007|isbn=978-1-59385-213-9|pages=17–20}}</ref> Early insecure attachment does not necessarily predict difficulties, but it is a liability for the child, particularly if similar parental behaviours continue throughout childhood.<ref name="Karen pp. 248–66"/> Compared to that of securely attached children, the adjustment of insecure children in many spheres of life is not as soundly based, putting their future relationships in jeopardy. Although the link is not fully established by research and there are other influences besides attachment, secure infants are more likely to become socially competent than their insecure peers. Relationships formed with peers influence the acquisition of social skills, intellectual development and the formation of social identity. Classification of children's peer status (popular, neglected or rejected) has been found to predict subsequent adjustment.<ref name="Schaffer"/> Insecure children, particularly avoidant children, are especially vulnerable to family risk. Their social and behavioural problems increase or decline with deterioration or improvement in parenting. However, an early secure attachment appears to have a lasting protective function.<ref name=bercasapp>{{cite encyclopedia|year=2008|author=Berlin LJ, Cassidy J, Appleyard K|title=The Influence of Early Attachments on Other Relationships|encyclopedia=Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications| editors= Cassidy J, Shaver PR| publisher= Guilford Press|location= New York and London|pages=333–47|isbn=9781593858742}}</ref> As with attachment to parental figures, subsequent experiences may alter the course of development.<ref name="Schaffer"/> | |||

| ===Dismissive-avoidant attachment=== | |||

| The most concerning pattern is disorganized attachment. About 80% of maltreated infants are likely to be classified as disorganized, as opposed to about 12% found in non-maltreated samples. Only about 15% of maltreated infants are likely to be classified as secure. Children with a disorganized pattern in infancy tend to show markedly disturbed patterns of relationships. Subsequently their relationships with peers can often be characterised by a "]" pattern of alternate aggression and withdrawal. Affected maltreated children are also more likely to become maltreating parents. A minority of maltreated children do not, instead achieving secure attachments, good relationships with peers and non-abusive parenting styles.<ref name="Schaffer"/> The link between insecure attachment, particularly the disorganized classification, and the emergence of childhood ] is well-established, although it is a non-specific risk factor for future problems, not a ] or a direct cause of pathology in itself.<ref name="PPP"/> In the classroom, it appears that ] children are at an elevated risk for internalising disorders, and avoidant and disorganized children, for externalising disorders.<ref name=bercasapp/> | |||

| An infant with an dismissive-avoidant pattern of attachment will avoid or ignore the caregiver—showing little emotion when the caregiver departs or returns. The infant will not explore very much regardless of who is there. Infants classified as dismissive-avoidant (A) represented a puzzle in the early 1970s. They did not exhibit distress on separation, and either ignored the caregiver on their return (A1 subtype) or showed some tendency to approach together with some tendency to ignore or turn away from the caregiver (A2 subtype). Ainsworth and Bell theorized that the apparently unruffled behaviour of the avoidant infants was in fact a mask for distress, a hypothesis later evidenced through studies of the heart-rate of avoidant infants.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ainsworth MD, Bell SM | s2cid = 3942480 | title = Attachment, exploration, and separation: illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_child-development_1970-03_41_1/page/49 | journal = Child Development | volume = 41 | issue = 1 | pages = 49–67 | date = March 1970 | pmid = 5490680 | doi = 10.2307/1127388 | jstor = 1127388 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sroufe A, Waters E |year=1977 |title=Attachment as an Organizational Construct | url = https://archive.org/details/sim_child-development_1977-12_48_4/page/1184 |journal=Child Development |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=1184–1199 |citeseerx=10.1.1.598.3872 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-8624.1977.tb03922.x}}</ref> | |||

| One explanation for the effects of early attachment classifications may lie in the internal working model mechanism. Internal models are not just "pictures" but refer to the feelings aroused. They enable a person to anticipate and interpret another's behaviour and plan a response. If an infant experiences their caregiver as a source of security and support, they are more likely to develop a positive self-image and expect positive reactions from others. Conversely, a child from an abusive relationship with the caregiver may internalise a negative self-image and generalise negative expectations into other relationships. The internal working models on which attachment behaviour is based show a degree of continuity and stability. Children are likely to fall into the same categories as their primary caregivers indicating that the caregivers' internal working models affect the way they relate to their child. This effect has been observed to continue across three generations. Bowlby believed that the earliest models formed were the most likely to persist because they existed in the subconscious. Such models are not, however, impervious to change given further relationship experiences; a minority of children have different attachment classifications with different caregivers.<ref name="Schaffer"/> | |||

| Infants are depicted as dismissive-avoidant when there is: | |||

| There is some evidence that gender differences in attachment patterns of ] significance begin to emerge in middle childhood. Insecure attachment and early psychosocial stress indicate the presence of environmental risk (for example poverty, mental illness, instability, minority status, violence). This can tend to favour the development of strategies for earlier reproduction. However, different patterns have different adaptive values for males and females. Insecure males tend to adopt avoidant strategies, whereas insecure females tend to adopt anxious/ambivalent strategies, unless they are in a very high risk environment. ] is proposed as the endocrine mechanism underlying the reorganisation of insecure attachment in middle childhood.<ref name=delguid>{{cite journal|title=Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies|author=Del Giudice M|journal=Behavioral and Brain Sciences|year=2009|volume=32|pages=1–67|doi=10.1017/S0140525X09000016|pmid=19210806|issue=1 }}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|... conspicuous avoidance of the mother in the reunion episodes which is likely to consist of ignoring her altogether, although there may be some pointed looking away, turning away, or moving away ... If there is a greeting when the mother enters, it tends to be a mere look or a smile ... Either the baby does not approach his mother upon reunion, or they approach in "abortive" fashions with the baby going past the mother, or it tends to only occur after much coaxing ... If picked up, the baby shows little or no contact-maintaining behavior<!-- This is within a quote, might be the original spelling -->; he tends not to cuddle in; he looks away and he may squirm to get down.<ref name="Ainsworth, M.D.S, Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S." />}} | |||

| ==Attachment in adults== | |||

| {{See also|Attachment in adults|Attachment measures}} | |||

| Attachment theory was extended to adult ]s in the late 1980s by Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver. Four styles of attachment have been identified in adults: secure, anxious-preoccupied, dismissive-avoidant and fearful-avoidant. These roughly correspond to infant classifications: secure, insecure-ambivalent, insecure-avoidant and disorganized/disoriented. | |||

| Ainsworth's narrative records showed that infants avoided the caregiver in the stressful Strange Situation Procedure when they had a history of experiencing rebuff of attachment behaviour. The infant's needs were frequently not met and the infant had come to believe that communication of emotional needs had no influence on the caregiver. | |||