| Revision as of 17:18, 14 November 2009 editRich Farmbrough (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors1,725,948 editsm Delink dates (WP:MOSUNLINKDATES) using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:49, 17 January 2025 edit undoToBeFree (talk | contribs)Checkusers, Oversighters, Administrators128,163 edits Reverted 1 edit by Timeshifter (talk): Restoring stable revision after edit-warring block; WP:ONUS appliesTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Form of market-based economy}} | ||

| {{For|economic systems where markets (either free or regulated) are the primary allocation mechanism|Market economy}} | |||

| {{Liberalism sidebar|expand=all}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Free enterprise}} | |||

| {{Libertarianism sidebar|expanded=all}} | |||

| {{economic systems sidebar|coordination}} | |||

| A '''free market''' describes a ] without ] and ] by government except to regulate against force or fraud. The terminology is used by ]s and in popular culture. A free ] requires protection of property rights, but no regulation, no subsidization, no single ], and no governmental monopolies. It is the opposite of a ], where the government regulates prices or how property is used. | |||

| {{liberalism sidebar}} | |||

| In ], a '''free market''' is an economic ] in which the prices of goods and services are determined by ] expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ] or any other external authority. Proponents of the free market as a normative ideal contrast it with a ], in which a government intervenes in supply and demand by means of various methods such as ] or ]. In an idealized ], prices for goods and services are set solely by the bids and offers of the participants. | |||

| The theory holds that within the ideal free market, ] are voluntarily exchanged at a price arranged solely by the mutual consent of ] and ]. By definition, buyers and sellers do not ] each other, in the sense that they obtain each other's property rights without the use of physical force, threat of physical force, or fraud, nor are they coerced by a third party (such as by government via ]) <ref> Rothbard, Murray. The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics</ref> and they engage in trade simply because they both consent and believe that what they are getting is worth more than or as much as what they give up. Price is the result of buying and selling decisions en masse as described by the law of ]. | |||

| Scholars contrast the concept of a free market with the concept of a ] in fields of study such as ], ], ], and ]. All of these fields emphasize the importance in currently existing market systems of rule-making institutions external to the simple forces of supply and demand which create space for those forces to operate to control productive output and distribution. Although free markets are commonly associated with ] in contemporary usage and ], free markets have also been components in some forms of ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Bockman|first=Johanna|title=Markets in the name of Socialism: The Left-Wing origins of Neoliberalism|publisher=Stanford University Press|year=2011|isbn=978-0804775663}}</ref> | |||

| Free markets contrast sharply with '']s'' or '']s'', in which governments directly or indirectly regulate prices or supplies, which according to free market theory causes markets to be less efficient.<ref>Dictionary of Finance and Investment Terms. Barrons, 1995</ref> Where government intervention exists, the market is a ]. | |||

| Historically, free market has also been used synonymously with other economic policies. For instance proponents of ''laissez-faire'' capitalism may refer to it as free market capitalism because they claim it achieves the most economic freedom.<ref name="Popper 1994" /> In practice, governments usually intervene to reduce ] such as ]; although they may use markets to do so, such as ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Externalities: Prices Do Not Capture All Costs |first1=Thomas |last1=Helbling |url=https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/external.htm |access-date=2022-09-15 |website=Finance & Development |publisher=International Monetary Fund |language=en-US |archive-date=2022-09-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220915183424/https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/external.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In the marketplace the price of a good or service helps communicate consumer demand to producers and thus directs the allocation of resources toward consumer, as well as investor, satisfaction. In a free market, price is a result of a plethora of voluntary transactions, rather than political decree as in a controlled market. Through free competition between vendors for the provision of products and services, prices tend to decrease, and quality tends to increase. A free market is not to be confused with a ] where individuals have ] and there is ]. | |||

| == Economic systems == | |||

| Free market economics is closely associated with '']'' economic philosophy, which advocates approximating this condition in the real world by mostly confining government intervention in economic matters to regulating against force and fraud among market participants. Some free market advocates oppose ] as well, claiming that the market is more efficient at providing all valuable services of which ] and ] are no exception, that such services can be provided without direct taxation and that consent would be the basis of ] making it a morally consistent system. ]s, for example, would substitute ] agencies and ]. | |||

| === Capitalism === | |||

| {{Capitalism sidebar|expanded=concepts}} | |||

| Capitalism is an ] based on the ] of the ] and their operation for ].<ref>{{cite book |first1=Andrew S. |last1=Zimbalist |first2=Howard J. |last2=Sherman |first3=Stuart |last3=Brown |url=https://archive.org/details/comparingeconomi0000zimb_q8i6/page/6|title=Comparing Economic Systems: A Political-Economic Approach|year=1988|publisher=Harcourt College Pub|isbn=978-0155124035|pages=|quote=Pure capitalism is defined as a system wherein all of the means of production (physical capital) are privately owned and run by the capitalist class for a profit, while most other people are workers who work for a salary or wage (and who do not own the capital or the product).}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Rosser|first1=Mariana V.|title=Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y3Mr6TgalqMC&pg=PA7 |last2=Rosser|first2=J Barkley|year= 2003|publisher=MIT Press|isbn=978-0262182348|page=7|quote=In capitalist economies, land and produced means of production (the capital stock) are owned by private individuals or groups of private individuals organized as firms.}}</ref><ref name=":1">Chris Jenks. ''Core Sociological Dichotomies''. "Capitalism, as a mode of production, is an economic system of manufacture and exchange which is geared toward the production and sale of commodities within a market for profit, where the manufacture of commodities consists of the use of the formally free labor of workers in exchange for a wage to create commodities in which the manufacturer extracts surplus value from the labor of the workers in terms of the difference between the wages paid to the worker and the value of the commodity produced by him/her to generate that profit." London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi. Sage. p. 383.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Gilpin|first=Robert|title=The Challenge of Global Capitalism : The World Economy in the 21st Century|year=2018|publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0691186474|oclc=1076397003}}</ref> Central characteristics of capitalism include ], ]s, a ], private property and the recognition of ], ], and ].<ref>Heilbroner, Robert L. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171028232506/http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_C000053|date=28 October 2017}}. Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume, eds. ''The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics''. 2nd {{abbr|ed.|edition}} (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) {{doi|10.1057/9780230226203.0198}}.</ref><ref>Louis Hyman and Edward E. Baptist (2014). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150522065957/http://books.simonandschuster.com/American-Capitalism/Louis-Hyman/9781476784311|date=22 May 2015}}. ]. {{ISBN|978-1476784311}}.</ref> In a ], decision-making and investments are determined by every owner of wealth, property or production ability in ] and ]s whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Gregory|first1=Paul|title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems|last2=Stuart|first2=Robert|publisher=South-Western College Pub|year=2013|isbn=978-1285-05535-0|page=41|quote=Capitalism is characterized by private ownership of the factors of production. Decision making is decentralized and rests with the owners of the factors of production. Their decision making is coordinated by the market, which provides the necessary information. Material incentives are used to motivate participants.}}</ref> | |||

| ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include '']'' or free-market capitalism, ] and ]. Different ] feature varying degrees of free markets, ],<ref>{{cite book|last=Gregory and Stuart|first=Paul and Robert|title=The Global Economy and its Economic Systems|year=2013|publisher=South-Western College Pub|isbn=978-1285-05535-0|page=107|quote=Real-world capitalist systems are mixed, some having higher shares of public ownership than others. The mix changes when privatization or nationalization occurs. Privatization is when property that had been state-owned is transferred to private owners. ] occurs when privately owned property becomes publicly owned.}}</ref> obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned ]. The degree of ] in ] and the role of ] and ] as well as the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.<ref name="Modern Economics 1986, p. 54">''Macmillan Dictionary of Modern Economics'', 3rd Ed., 1986, p. 54.</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|last=Bronk|first=Richard|date=Summer 2000|title=Which model of capitalism?|url=http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html|url-status=live|magazine=]|publisher=OECD|volume=1999|issue=221–22|pages=12–15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180406200423/http://oecdobserver.org/news/archivestory.php/aid/345/Which_model_of_capitalism_.html|archive-date=6 April 2018|access-date=6 April 2018}}</ref> The extent to which different markets are free and the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most of the existing capitalist economies are ] that combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases ].<ref name="Stilwell">Stilwell, Frank. "Political Economy: the Contest of Economic Ideas". First Edition. Oxford University Press. Melbourne, Australia. 2002.</ref> | |||

| In ], a ] is a system for ] goods within a society: ] mediated by ] within the market determines who gets what and what is produced, rather than the state. Early proponents of a free-market economy in 18th century Europe contrasted it with the ], ], and ] economies which preceded it. | |||

| ] have existed under many ] and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies—marked by a universalization of ]-based ], a consistently large and system-wide ] who must work for wages (the ]) and a ] which owns the means of production—developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the ]. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the ] and continue to spread. Capitalism has been shown to be strongly correlated with ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Sy|first=Wilson N.|date=18 September 2016|title=Capitalism and Economic Growth Across the World|location=Rochester, NY|doi=10.2139/ssrn.2840425 |ssrn=2840425|s2cid=157423973 |quote=For 40 largest countries in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) database, it is shown statistically that capitalism, between 2003 and 2012, is positively correlated significantly to economic growth.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Supply and demand== | |||

| {{Main|Supply and demand}} | |||

| {{copypaste|October 2009|section|http://www.donsheelen.org/page14.aspx}} | |||

| Supply and demand are always equal as they are the two sides of the same set of transactions, and discussions of "imbalances" are a muddled and indirect way of referring to price{{Citation needed|date=September 2009}}. However, in an unmeasurable qualitative sense, demand for an item (such as goods or services) refers to the market pressure from people trying to buy it. They will "bid" money for the item, while sellers offer the item for money. When the bid matches the offer, a transaction can easily occur (even automatically, as in a typical ]). In reality, most shops and markets do not resemble the stock market, and there are significant costs and barriers to "shopping around" (comparison shopping). | |||

| === Georgism === | |||

| When demand exceeds supply, suppliers can raise the price, but when supply exceeds demand, suppliers will have to decrease the price in order to make sales. Consumers who can afford the higher prices may still buy, but others may forgo the purchase altogether, demand a better price, buy a similar item, or shop elsewhere. As the price rises, suppliers may also choose to increase production. Or more suppliers may enter the business. | |||

| {{main|Georgism}} | |||

| For classical economists such as ], the term free market refers to a market free from all forms of economic privilege, monopolies and artificial scarcities.<ref name="Popper 1994"/> They say this implies that ]s, which they describe as profits generated from a lack of ], must be reduced or eliminated as much as possible through free competition. | |||

| Economic theory suggests the returns to ] and other ]s are economic rents that cannot be reduced in such a way because of their perfect inelastic supply.<ref>], '']'' ], Part 2, Article I: Taxes upon the Rent of Houses.</ref> Some economic thinkers emphasize the need to share those rents as an essential requirement for a well functioning market. It is suggested this would both eliminate the need for regular taxes that have a negative effect on trade (see ]) as well as release land and resources that are speculated upon or monopolised, two features that improve the competition and free market mechanisms. ] supported this view by the following statement: "Land is the mother of all monopoly".<ref>House Of Commons May 4th; King's Theatre, Edinburgh, July 17</ref> The American economist and social philosopher ], the most famous proponent of this thesis, wanted to accomplish this through a high ] that replaces all other taxes.<ref>Backhaus, "Henry George's Ingenious Tax," pp. 453–458.</ref> Followers of his ideas are often called ] or geoists and ]. | |||

| ==Gourmet coffee and electronics as examples of market forces in economics== | |||

| For example, the ] business, pioneered in the US by ], revealed a demand for high quality fresh coffee. Further, the Starbucks sales growth showed that consumers would pay significantly more for this type of coffee. Other food service retailers, such as ], ], and ], began offering such coffee to help satisfy the demand. | |||

| ], one of the founders of the ] who helped formulate the ], had a very similar view. He argued that free competition could only be realized under conditions of state ownership of natural resources and land. Additionally, income taxes could be eliminated because the state would receive income to finance public services through owning such resources and enterprises.<ref>{{cite book |last= Bockman|first= Johanna |title= Markets in the name of Socialism: The Left-Wing origins of Neoliberalism|publisher= Stanford University Press|year= 2011|isbn= 978-0804775663|page = 21|quote= For Walras, socialism would provide the necessary institutions for free competition and social justice. Socialism, in Walras's view, entailed state ownership of land and natural resources and the abolition of income taxes. As owner of land and natural resources, the state could then lease these resources to many individuals and groups which would eliminate monopolies and thus enable free competition. The leasing of land and natural resources would also provide enough state revenue to make income taxes unnecessary, allowing a worker to invest his savings and become 'an owner or capitalist at the same time that he remains a worker.}}</ref> | |||

| Increased supply can indirectly result in lower prices, particularly with ]s and other electronic devices. ] techniques have been steadily reducing prices 20 to 30% per year since the 1960s. {{Citation needed|date=November 2008}} The functions of a multi-million dollar mainframe computer in the 1960s could be performed by a $100 computer in the 2000s. | |||

| === ''Laissez-faire'' === | |||

| ==Spontaneous order or "Invisible hand"== | |||

| {{main|Laissez-faire}} | |||

| {{Main|Invisible hand|Spontaneous order}} | |||

| The ''laissez-faire'' principle expresses a preference for an absence of non-market pressures on prices and wages such as those from discriminatory government ]es, ], ]s, ], or ]. In ''The Pure Theory of Capital'', ] argued that the goal is the preservation of the unique information contained in the price itself.<ref name="hayek_pure">Hayek, Friedrich (1941). ''The Pure Theory of Capital''.</ref> | |||

| ] argues for the classical liberal view that market economies allow ]; that is, "a more efficient allocation of societal resources than any design could achieve."<ref>Hayek cited. Petsoulas, Christian. ''Hayek's Liberalism and Its Origins: His Idea of Spontaneous Order and the Scottish Enlightenment''. Routledge. 2001. p. 2</ref> According to this view, in market economies sophisticated business networks are formed which produce and distribute goods and services throughout the economy. This network was not designed, but ''emerged'' as a result of decentralized individual economic decisions. Supporters of the idea of spontaneous order trace their views to the concept of the ] proposed by ] in '']'' who said that the individual who: | |||

| According to Karl Popper, the idea of the free market is paradoxical, as it requires interventions towards the goal of preventing interventions.<ref name="Popper 1994">{{cite book|last=Popper|first=Karl|title=The Open Society and Its Enemies|publisher=Routledge Classics|year=1994|isbn=978-0415610216|pages=712}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"intends only his own gain is led by an ''invisible hand'' to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the good." ('']'')</blockquote> | |||

| Although ''laissez-faire'' has been commonly associated with ], there is a similar economic theory associated with ] called left-wing or socialist ''laissez-faire'', also known as ], ] and ] to distinguish it from ''laissez-faire'' capitalism.<ref>Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). ''Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty''. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia</ref><ref>"It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism." Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). ''Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty''. Brooklyn, NY: Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. p. back cover.</ref><ref>"But there has always been a market-oriented strand of libertarian socialism that emphasizes voluntary cooperation between producers. And markets, properly understood, have always been about cooperation. As a commenter at Reason magazine's Hit&Run blog, remarking on ]'s link to the Kelly article, put it: "every trade is a cooperative act." In fact, it's a fairly common observation among market anarchists that genuinely free markets have the most legitimate claim to the label "socialism." {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160310111716/https://c4ss.org/content/670 |date=2016-03-10 }} by ] at website of Center for a Stateless Society.</ref> Critics of ''laissez-faire'' as commonly understood argue that a truly ''laissez-faire'' system would be ] and ].<ref>Nick Manley, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210818131348/http://c4ss.org/content/27009 |date=2021-08-18 }}.</ref><ref>Nick Manley, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210516192528/https://c4ss.org/content/27062 |date=2021-05-16 }}.</ref> American ] such as ] saw themselves as economic free-market socialists and political individualists while arguing that their "anarchistic socialism" or "individual anarchism" was "consistent ]".<ref>Tucker, Benjamin (1926). ''Individual Liberty: Selections from the Writings of Benjamin R. Tucker''. New York: Vanguard Press. pp. 1–19.</ref> | |||

| Smith pointed out that one does not get one's dinner by appealing to the brother-love of the butcher, the farmer or the baker. Rather one appeals to their self interest, and pays them for their labour. | |||

| === Socialism === | |||

| {{cquote|It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages."<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith |first=Adam |title=] |origyear=1776 |url=http://www.econlib.org/LIBRARY/Smith/smWN.html |accessdate=2007-12-08 |chapter=2 |chapterurl=http://www.econlib.org/LIBRARY/Smith/smWN1.html#B.I%2C%20Ch.2%2C%20Of%20the%20Principle%20which%20gives%20Occasion%20to%20the%20Division%20of%20Labour%2C%20benevolence | |||

| {{main|Socialism}} | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| {{See also|Socialist economics}} | |||

| Various forms of ] based on free markets have existed since the 19th century. Early notable socialist proponents of free markets include ], ] and the ]s. These economists believed that genuinely free markets and ] could not exist within the ] conditions of ]. These proposals ranged from various forms of ]s operating in a free-market economy such as the ] system proposed by Proudhon, to state-owned enterprises operating in unregulated and open markets. These models of socialism are not to be confused with other forms of market socialism (e.g. the ]) where publicly owned enterprises are coordinated by various degrees of ], or where capital good prices are determined through marginal cost pricing. | |||

| Advocates of free-market socialism such as ] argue that genuinely free markets are not possible under conditions of private ownership of productive property. Instead, he contends that the class differences and inequalities in income and power that result from private ownership enable the interests of the dominant class to skew the market to their favor, either in the form of monopoly and market power, or by utilizing their wealth and resources to legislate government policies that benefit their specific business interests. Additionally, Vanek states that workers in a socialist economy based on cooperative and self-managed enterprises have stronger incentives to maximize productivity because they would receive a share of the profits (based on the overall performance of their enterprise) in addition to receiving their fixed wage or salary. The stronger incentives to maximize productivity that he conceives as possible in a socialist economy based on cooperative and self-managed enterprises might be accomplished in a free-market economy if ] were the norm as envisioned by various thinkers including ] and ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817073532/http://www.ru.org/index.php/30-economics/357-cooperative-economics-an-interview-with-jaroslav-vanek |date=2021-08-17 }}. Interview by Albert Perkins. Retrieved March 17, 2011.</ref> | |||

| Supporters of this view claim that spontaneous order is superior to any order that does not allow individuals to make their own choices of what to produce, what to buy, what to sell, and at what prices, due to the number and complexity of the factors involved. They further believe that any attempt to implement central planning will result in more disorder, or a less efficient production and distribution of goods and services. | |||

| Socialists also assert that ] leads to an excessively skewed distributions of income and economic instabilities which in turn leads to social instability. Corrective measures in the form of ], re-distributive taxation and regulatory measures and their associated administrative costs which are required create agency costs for society. These costs would not be required in a self-managed socialist economy.<ref name="The Political Economy of Socialism 1982. pp. 197–198">''The Political Economy of Socialism'', by Horvat, Branko (1982), pp. 197–198.</ref> | |||

| ==Economic equilibrium== | |||

| {{Main|Economic equilibrium}} | |||

| ] has demonstrated, with varying degrees of mathematical rigor over time, that under certain conditions of ], the law of ] predominates in this ideal free and competitive market, influencing prices toward an ] that balances the demands for the products against the supplies.<ref>, by ]</ref><ref>''Theory of Value'', by ]</ref> At these equilibrium prices, the market distributes the products to the purchasers according to each purchaser's preference (or utility) for each product and within the relative limits of each buyer's ]. This result is described as market efficiency, or more specifically a ]. | |||

| Criticism of market socialism comes from two major directions. Economists ] and ] argued that socialism as a theory is not conducive to democratic systems<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hayek |first=F. |date=1949-03-01 |title=The Intellectuals and Socialism |url=https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol16/iss3/7 |journal=University of Chicago Law Review |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=417–433 |doi=10.2307/1597903 |jstor=1597903 |issn=0041-9494 |access-date=2022-10-27 |archive-date=2022-10-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221027052633/https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol16/iss3/7/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and even the most benevolent state would face serious implementation problems.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Stigler |first=George J. |date=1992 |title=Law or Economics? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/725548 |journal=The Journal of Law & Economics |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=455–468 |doi=10.1086/467262 |jstor=725548 |s2cid=154114758 |issn=0022-2186 |access-date=2022-10-27 |archive-date=2022-10-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221027052632/https://www.jstor.org/stable/725548 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| This equilibrating behavior of free markets requires certain assumptions about their agents, collectively known as Perfect Competition, which therefore cannot be results of the market that they create. Among these assumptions are complete information, interchangeable goods and services, and lack of market power, that obviously cannot be fully achieved. The question then is what approximations of these conditions guarantee approximations of market efficiency, and which failures in competition generate overall market failures. Several Nobel Prizes in Economics have been awarded for analyses of market failures due to ]. | |||

| More modern criticism of socialism and ] implies that even in a democratic system, socialism cannot reach the desired efficient outcome. This argument holds that democratic majority rule becomes detrimental to enterprises and industries, and that the formation of ] distorts the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Shleifer |first1=Andrei |last2=Vishny |first2=Robert W |date=1994 |title=Politics of Market Socialism |url=https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/politics_market_socialism.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140202181443/http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/politics_market_socialism.pdf |archive-date=2014-02-02 |url-status=live |journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=165–176|doi=10.1257/jep.8.2.165 |s2cid=152437398 }}</ref> | |||

| Some models in ]<ref name="ball"/> have shown that when agents are allowed to interact locally in a free market (ie. their decisions depend not only on utility and purchasing power, but also on their peers' decisions), prices can become unstable and diverge from the equilibrium, often in an abrupt manner.The behavior of the free market is thus said to be non-linear (a pair of agents bargaining for a purchase will agree on a different price than 100 identical pairs of agents doing the identical purchase). ] and the type of ] behavior often observed in stock markets are quoted as real life examples of non-equilibrium price trends. Laissez-faire free-market advocates, especially ] followers, often dismiss this endogenous theory, and blame external influences, such as weather, commodity prices, technological developments, and government meddling for non-equilibrium prices. | |||

| == Concepts == | |||

| ==Distribution of wealth== | |||

| === Economic equilibrium === | |||

| {{Main|Distribution of wealth}} | |||

| {{main|Economic equilibrium}} | |||

| The distribution of purchasing power in an economy depends to a large extent on the nature of government intervention, ], ] and ], but also on other, lesser factors such as family relationships, ], ]s and so on. Many theories describing the operation of a free market focus primarily on the markets for consumer products, and their description of the labor market or financial markets tends to be more complicated and controversial. The free market can be seen as facilitating a form of decision-making through what is known as ], where a purchase of a product is tantamount to casting a vote for a producer to continue producing that product. | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] has demonstrated that, under certain theoretical conditions of ], the law of ] influences prices toward an ] that balances the demands for the products against the supplies.<ref>''Theory of Value'' by ].</ref>{{full citation needed|date=February 2022}} At these equilibrium prices, the market distributes the products to the purchasers according to each purchaser's preference or ] for each product and within the relative limits of each buyer's ]. This result is described as market efficiency, or more specifically a ]. | |||

| === Low barriers to entry === | |||

| The effect of ] on society's and individuals' ] remains a subject of controversy. ] and ] have shown that under certain idealized conditions, a system of free trade leads to ], but the traditional ] paradigm within economics is now being challenged by the new Greenwald-] paradigm (1986)<ref name=GREENWALD>GREENWALD, Bruce and STIGLITZ, Joseph E. 1986 Externalities in Economies with Imperfect Information and Incomplete Markets, Quarterly Journal of Economics, no. 90.</ref>. Many advocates of free markets, most notably ], have also argued that there is a direct relationship between economic growth and economic freedom, though this assertion is much harder to prove empirically, as the continuous debates among scholars on methodological issues in empirical studies of the connection between economic freedom and economic growth clearly indicate:<ref name=COLE> Econ Journal Watch, | |||

| {{main|Barriers to entry}} | |||

| Volume 4, Number 1, January 2007, pp 71–78.</ref><ref name=HAAN> Econ Journal Watch, Volume 3, Number 3, September 2006, pp 407–411.</ref><ref name=SECOND> Econ Journal Watch, | |||

| A free market does not directly require the existence of competition; however, it does require a framework that freely allows new market entrants. Hence, competition in a free market is a consequence of the conditions of a free market, including that market participants not be obstructed from following their ]. | |||

| Volume 4, Number 1, January 2007, pp 79–82.</ref>. "there were a few attempts to study relationship between growth and economic freedom | |||

| prior to the very recent availability of the Fraser data. These were useful but had to use incomplete and subjective variables"<ref name=CHICAGO> Journal of Developing Areas, Vol.32, No.3, Spring 1998, 327-338. Publisher: Western Illinois University.</ref>. ] and Robert Axtell have attempted to predict the properties of free markets empirically in the agent-based computer simulation "]". They came to the conclusion that, again under idealized conditions, free markets lead to a ] of wealth<ref name="ball">''Critical Mass'' - ], ISBN 0-09-945786-5</ref> . | |||

| === Perfect competition and market failure === | |||

| On the other hand more recent research, specially the one led by ] seems to contradict Friedman's conclusions. According to Boettke: | |||

| {{main|Perfect competition|Market failure}} | |||

| An absence of any of the conditions of perfect competition is considered a ]. Regulatory intervention may provide a substitute force to counter a market failure, which leads some economists to believe that some forms of market regulation may be better than an unregulated market at providing a free market.<ref name="Popper 1994" /> | |||

| === Spontaneous order === | |||

| ::Once incomplete and imperfect information are introduced, ] defenders of the market system cannot sustain descriptive claims of the ] of the real world. Thus, ]'s use of rational-expectations equilibrium assumptions to achieve a more realistic understanding of capitalism than is usual among rational-expectations theorists leads, paradoxically, to the conclusion that capitalism deviates from the model in a way that justifies state action--]--as a remedy.<ref name=BOETTKE></ref> | |||

| {{main|Spontaneous order}} | |||

| {{See also|Invisible hand}} | |||

| ] popularized the view that market economies promote ] which results in a better "allocation of societal resources than any design could achieve".<ref>Hayek cited. Petsoulas, Christina. ''Hayek's Liberalism and Its Origins: His Idea of Spontaneous Order and the Scottish Enlightenment''. Routledge. 2001. p. 2.</ref> According to this view, market economies are characterized by the formation of complex transactional networks that produce and distribute goods and services throughout the economy. These networks are not designed, but they nevertheless emerge as a result of decentralized individual economic decisions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Jaffe |first=Klaus |date=2014 |title=Agent Based Simulations Visualize Adam Smith's Invisible Hand by Solving Friedrich Hayek's Economic Calculus |url=http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2695557 |journal=SSRN Electronic Journal |language=en |doi=10.2139/ssrn.2695557 |arxiv=1509.04264 |s2cid=17075259 |issn=1556-5068}}</ref> The idea of spontaneous order is an elaboration on the ] proposed by ] in '']''. About the individual, Smith wrote: | |||

| <blockquote>By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.<ref>Smith, Adam (1827). ''The Wealth of Nations''. Book IV. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144732/https://books.google.com/books?id=rpMuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA184 |date=2023-01-18 }}.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Smith pointed out that one does not get one's dinner by appealing to the brother-love of the butcher, the farmer or the baker. Rather, one appeals to their self-interest and pays them for their labor, arguing: | |||

| ==Laissez-faire economics== | |||

| <blockquote>It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.<ref>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Adam|author-link=Adam Smith|title=The Wealth of Nations|place=London|publisher=W. Strahan and T. Cadell|year=1776|volume=1|chapter=2}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{Main|Laissez-faire economics}} | |||

| The necessary components for the functioning of an idealized free market include the complete absence of artificial price pressures from taxes, subsidies, ]s, or government regulation (other than protection from coercion and theft, and no ] (usually classified as ] by free market advocates) like the ], ], arguably ]s, etc. | |||

| Supporters of this view claim that spontaneous order is superior to any order that does not allow individuals to make their own choices of what to produce, what to buy, what to sell and at what prices due to the number and complexity of the factors involved. They further believe that any attempt to implement central planning will result in more disorder, or a less efficient production and distribution of goods and services. | |||

| ===Deregulation=== | |||

| {{Main|Deregulation}} | |||

| In an absolutely ''free-market economy'', all capital, goods, services, and money flow transfers are unregulated by the government except to stop collusion or fraud that may take place among market participants. {{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} As this protection must be funded, such a government taxes only to the extent necessary to perform this function, if at all. This state of affairs is also known as '']''. | |||

| Internationally, free markets are advocated by proponents of ]; in Europe this is usually simply called ''liberalism''. In the ], support for free market is associated most with ]. Since the 1970s, promotion of a global free-market economy, ] and ], is often described as ]. | |||

| The term ''free market economy'' is sometimes used to describe some economies that exist today (such as ]), but pro-market groups would only accept that description if the government practices ''laissez-faire'' policies, rather than state intervention in the economy.{{Specify|date=January 2007}} An economy that contains significant economic interventionism by government, while still retaining some characteristics found in a free market is often called a '']''. | |||

| Critics such as political economist ] question whether a spontaneously ordered market can exist, completely free of distortions of political policy, claiming that even the ostensibly freest markets require a state to exercise coercive power in some areas, namely to enforce ]s, govern the formation of ]s, spell out the rights and obligations of ]s, shape who has standing to bring legal actions and define what constitutes an unacceptable ].<ref>]; ] (2010). ''Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer – and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class''. Simon & Schuster. p. 55.</ref> | |||

| ===Low barriers to entry=== | |||

| A free market does not require the existence of competition, however it does require that there are no barriers to new market entrants. Hence, in the lack of coercive barriers it is generally understood that competition flourishes in a free market environment. It often suggests the presence of the ], although neither a profit motive or profit itself are necessary for a free market. All modern free markets are understood to include ]s, both individuals and ]es. Typically, a modern free market economy would include other features, such as a ] and a ] sector, but they do not define it. | |||

| == |

=== Supply and demand === | ||

| {{main|Supply and demand}} | |||

| In a truly free market economy, money would not be monopolized by ] laws or by a central bank, in order to receive ] from the transactions or to be able to issue ]s. {{Citation needed|date=January 2007}} ] (advocates of minimal government) contend that the so called "coercion" of taxes is essential for the market's survival, and a market free from taxes may lead to no market at all. By definition, there is no market without private property, and private property can only exist while there is an entity that defines and defends it. Traditionally, the State defends private property and defines it by issuing ownership titles, and also nominates the central authority to print or mint currency. "Free market anarchists" disagree with the above assessment– they maintain that private property and free markets can be protected by voluntarily-funded services under the concept of ] and ]<ref></ref><ref></ref>. A free market could be defined alternatively as a tax-free market, independent of any central authority, which uses as medium of exchange such as money, even in the absence of the State. It is disputed, however, whether this hypothetical stateless market could function. | |||

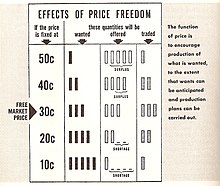

| Demand for an item (such as a good or service) refers to the economic market pressure from people trying to buy it. Buyers have a maximum price they are willing to pay for an item, and sellers have a minimum price at which they are willing to offer their product. The point at which the supply and demand curves meet is the equilibrium price of the good and quantity demanded. Sellers willing to offer their goods at a lower price than the equilibrium price receive the difference as ]. Buyers willing to pay for goods at a higher price than the equilibrium price receive the difference as ].<ref name="Judd1997">{{cite journal| doi = 10.1016/S0165-1889(97)00010-9| title = Computational economics and economic theory: Substitutes or complements?| journal = ]| volume = 21| issue = 6| pages = 907–942| year = 1997| last1 = Judd| first1 = K. L.| s2cid = 55347101| url = http://www.nber.org/papers/t0208.pdf| access-date = 2019-08-08| archive-date = 2020-05-20| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200520052928/https://www.nber.org/papers/t0208.pdf| url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| The model is commonly applied to wages in the market for labor. The typical roles of supplier and consumer are reversed. The suppliers are individuals, who try to sell (supply) their labor for the highest price. The consumers are businesses, which try to buy (demand) the type of labor they need at the lowest price. As more people offer their labor in that market, the equilibrium wage decreases and the equilibrium level of employment increases as the supply curve shifts to the right. The opposite happens if fewer people offer their wages in the market as the supply curve shifts to the left.<ref name="Judd1997"/> | |||

| ==Ethical justification== | |||

| The ethical ] of free markets takes two forms. One appeals to the intrinsic moral superiority of autonomy and freedom (in the market), see ]. The other is a form of ]—a belief that decentralised planning by a multitude of individuals making free economic decisions produces ''better results'' in regard to a more organized, efficient, and productive economy, than does a centrally-planned economy where a central agency decides what is produced, and allocates goods by non-price mechanisms. An older version of this argument is the ] of the ], familiar from the work of ]. | |||

| In a free market, individuals and firms taking part in these transactions have the liberty to enter, leave and participate in the market as they so choose. Prices and quantities are allowed to adjust according to economic conditions in order to reach equilibrium and allocate resources. However, in many countries around the world governments seek to intervene in the free market in order to achieve certain social or political agendas.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wps.pearsoned.co.uk/ema_uk_he_sloman_econbus_3/18/4748/1215583.cw/ |title=Chapter 20: Reasons for government intervention in the market |access-date=2014-06-06 |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140522012501/http://wps.pearsoned.co.uk/ema_uk_he_sloman_econbus_3/18/4748/1215583.cw/ |archive-date=2014-05-22 }}</ref> Governments may attempt to create ] or ] by intervening in the market through actions such as imposing a ] (price floor) or erecting ] (price ceiling). | |||

| Modern theories of ] say the internal organization of a system can increase automatically without being guided or managed by an outside source. When applied to the market, as an ethical justification, these theories appeal to its ] as a self-organising entity. Other philosophies such as some forms of ] (especially that of that 19th century) and ] anarchism believe that in a free market competition would cause prices of goods and services to align with the labor embodied in those things. This goes against the contemporary mainstream view, which is held by most contemporary individualist anarchists, that prices would accord to the ] of these things irrespective of the labor embodied in them. | |||

| Other lesser-known goals are also pursued, such as in the United States, where the federal government subsidizes owners of fertile land to not grow crops in order to prevent the supply curve from further shifting to the right and decreasing the equilibrium price. This is done under the justification of maintaining farmers' profits; due to the relative ] of demand for crops, increased supply would lower the price but not significantly increase quantity demanded, thus placing pressure on farmers to exit the market.<ref>{{cite news |title=Farm Program Pays $1.3 Billion to People Who Don't Farm |newspaper=] |date=2 July 2006 |access-date=3 June 2014 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/01/AR2006070100962.html |archive-date=4 September 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210904195617/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/01/AR2006070100962.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Those interventions are often done in the name of maintaining basic assumptions of free markets such as the idea that the costs of production must be included in the price of goods. Pollution and depletion costs are sometimes not included in the cost of production (a manufacturer that withdraws water at one location then discharges it polluted downstream, avoiding the cost of treating the water), therefore governments may opt to impose regulations in an attempt to try to internalize all of the cost of production and ultimately include them in the price of the goods. | |||

| ==Index of economic freedom== | |||

| The ], a ] ], tried to identify the key factors which allow to measure the degree of freedom of economy of a particular country. In 1986 they introduced ], which is based on some fifty variables. This and other similar indices do not ''define'' a free market, but measure the ''degree'' to which a modern economy is free, meaning in most cases free of state intervention. The variables are divided into the following major groups: | |||

| *Trade policy, | |||

| *Fiscal burden of government, | |||

| *Government intervention in the economy, | |||

| *Monetary policy, | |||

| *Capital flows and foreign investment, | |||

| *Banking and finance, | |||

| *Wages and prices, | |||

| *Property rights, | |||

| *Regulation, and | |||

| *Informal market activity. | |||

| Each group is assigned a numerical value between 1 and 5; IEF is the arithmetical mean of the values, rounded to the hundredth. Initially, countries which were traditionally considered capitalistic received high ratings, but the method improved over time. Some economists, like ] and other ] have argued that there is a direct relationship between economic growth and economic freedom, but this assertion has not been proven yet, both theoretically and empirically. Continuous debates among scholars on methodological issues in empirical studies of the connection between economic freedom and economic growth still try to find out what is the relationship, if any.<ref name="COLE"/><ref name="HAAN"/><ref name="SECOND"/>.<ref name="CHICAGO"/>. | |||

| Advocates of the free market contend that government intervention hampers economic growth by disrupting the efficient allocation of resources according to supply and demand while critics of the free market contend that government intervention is sometimes necessary to protect a country's economy from better-developed and more influential economies, while providing the stability necessary for wise long-term investment. ] argued against ], ] and ], particularly as practiced in the ] and ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.columbia.edu/~esp2/WSJ%20Whitehouse%20Article.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100625233550/http://www.columbia.edu/%7Eesp2/WSJ%20Whitehouse%20Article.pdf |archive-date=2010-06-25 |url-status=live|title=Ip, Greg and Mark Whitehouse, "How Milton Friedman Changed Economics, Policy and Markets", ''Wall Street Journal Online'' (November 17, 2006).}}</ref> while ] cites the examples of post-war Japan and the growth of South Korea's steel industry as positive examples of government intervention.<ref>"]", Ha-Joon Chang, Bloomsbury Press, {{ISBN|978-1596915985}}{{page needed|date=March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ::"In recent years a significant amount of work has been devoted to the investigation of a possible connection between the political system and economic growth. For a variety of reasons there is no consensus about that relationship, especially not about the direction of causality, if any." <small>(AYAL & KARRAS, 1998, p.2)</small><ref name="CHICAGO"/> | |||

| == Reception == | |||

| ==History and ideology== | |||

| {{undue weight|date=November 2023}} | |||

| Some theorists might argue that a free market is a natural form of social organization, and that a free market will arise in any society where it is not obstructed (ie ], ]). The consensus among ] is that the free market economy is a specific historic phenomenon, and that it emerged in late medieval and early-modern Europe. Other economic historians see elements of the free market in the economic systems of ], and in some non-western societies. By the 19th century the market certainly had organized political support, in the form of ]. However, it is not clear if the support preceded the emergence of the market or followed it. Some historians see it as the result of the success of early liberal ], combined with the specific interests of the ]. | |||

| === Criticism === | |||

| {{See also|Criticism of capitalism}} | |||

| Critics of a ''laissez-faire'' free market have argued that in real world situations it has proven to be susceptible to the development of ] monopolies.<ref>{{cite book|last=Tarbell|first=Ida|author-link=Ida Tarbell|title=The History of the Standard Oil Company|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924096224799|publisher=McClure, Phillips and Co.|year=1904}}</ref> Such reasoning has led to government intervention, e.g. the ]. Critics of the free market also argue that it results in significant ], ], or ], in order to allow markets to function more freely. | |||

| ===Marxism=== | |||

| In ] theory, the idea of the free market simply expresses the underlying long-term transition from ] to ]. Note that the views on this issue - emergence or implementation - do not necessarily correspond to pro-market and anti-market positions. ]s would dispute that the market was enforced through government policy, since they believe it is a ] and ] agree with them because they as well believe it is evolutionary, although with a different end. | |||

| Critics of a free market often argue that some market failures require government intervention.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Free market |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/free-market |access-date=2022-10-15 |website=] |language=en |archive-date=2022-10-20 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221020092442/https://www.britannica.com/topic/free-market |url-status=live }}</ref> Economists ], ], ], and ] have responded by arguing that markets can internalize or adjust to supposed market failures.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===Liberalism=== | |||

| Support for the free market as an ordering principle of society is above all associated with ], especially during the 19th century. (In Europe, the term 'liberalism' retains its ] as the ideology of the free market, but in American and Canadian usage it came to be associated with government intervention, and acquired a ] meaning for supporters of the free market.) Later ideological developments, such as ], ] and ] also support the free market, and insist on its pure form. Although the ] shares a generally similar form of economy, usage in the United States and Canada is to refer to this as ], while in Europe 'free market' is the preferred neutral term. ] (American and Canadian usage), and in Europe ], seek only to mitigate what they see as the problems of an unrestrained free market, and accept its existence as such. | |||

| Two prominent Canadian authors argue that government at times has to intervene to ensure competition in large and important industries. ] illustrates this roughly in her work '']'' and ] more humorously illustrates this through various examples in ''The Collapse of Globalism and the Reinvention of the World''.<ref name="The End of Globalism. Saul, John">Saul, John ''The End of Globalism''.</ref> While its supporters argue that only a free market can create healthy competition and therefore more business and reasonable prices, opponents say that a free market in its purest form may result in the opposite. According to Klein and Ralston, the merging of companies into giant corporations or the privatization of government-run industry and national assets often result in monopolies or oligopolies requiring government intervention to ] and reasonable prices.<ref name="The End of Globalism. Saul, John"/> | |||

| To most ]s, there is simply no free market yet, given the degree of state intervention in even the most 'capitalist' of countries. From their perspective, those who say they favor a "free market" are speaking in a relative, rather than an absolute, sense—meaning (in libertarian terms) they wish that ] be kept to the minimum that is necessary to maximize economic freedom (such necessary coercion would be taxation, for example) and to maximize market efficiency by lowering trade barriers, making the tax system neutral in its influence on important decisions such as how to raise capital, e.g., eliminating the ] on dividends so that equity financing is not at a disadvantage vis-a-vis debt financing. However, there are some such as ] who would not even allow for taxation and governments, instead preferring protectors of economic freedom in the form of private contractors. | |||

| Another form of market failure is ], where transactions are made to profit from short term fluctuation, rather from the ] of the companies or products. This criticism has been challenged by historians such as ], who argued that monopolies have historically failed to form even in the absence of antitrust law.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170216010448/https://fee.org/articles/41-rockefellers-standard-oil-company-proved-that-we-needed-anti-trust-laws-to-fight-such-market-monopolies/ |date=2017-02-16 }}, '']'', January 23, 2015. Retrieved December 20, 2016.</ref>{{unreliable source?|reason=fringe advocacy source|date=October 2021}} This is because monopolies are inherently difficult to maintain as a company that tries to maintain its monopoly by buying out new competitors, for instance, is incentivizing newcomers to enter the market in hope of a buy-out. Furthermore, according to writer Walter Lippman and economist Milton Friedman, historical analysis of the formation of monopolies reveals that, contrary to popular belief, these were the result not of unfettered market forces, but of legal privileges granted by government.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2021-04-25|title=Why We Need To Re-think Friedman's Ideas About Monopolies|url=https://promarket.org/2021/04/25/milton-friedman-monopoly-self-interest/|access-date=2021-09-27|website=ProMarket|language=en-US|archive-date=2021-09-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927191628/https://promarket.org/2021/04/25/milton-friedman-monopoly-self-interest/|url-status=live}}</ref>{{unreliable source?|reason=fringe advocacy source|date=October 2021}} | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| Critics dispute the claim that in practice free markets create ], or even increase ] over the ]. Whether the marketplace ''should be'' or ''is'' free is disputed; many assert that government intervention is necessary to remedy ] that is held to be an inevitable result of absolute adherence to free market principles. These failures range from ] services to ], and some would argue, to health care. This is the central argument of those who argue for a mixed market, free at the base, but with government oversight to control social problems. | |||

| American philosopher and author ] has derisively termed what he perceives as ]tic arguments for '']'' economic policies as ]. West has contended that such mentality "trivializes the concern for public interest" and "makes money-driven, poll-obsessed elected officials deferential to corporate goals of profit – often at the cost of the common good".<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141015220208/http://www.theglobalist.com/cornel-west-democracy-matters/ |date=2014-10-15 }}, '']'', January 24, 2005. Retrieved October 9, 2014.</ref> American political philosopher ] contends that in the last thirty years the United States has moved beyond just having a market economy and has become a market society where literally everything is for sale, including aspects of social and civic life such as education, access to justice and political influence.<ref>] (June 2013). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150521110607/http://www.ted.com/talks/michael_sandel_why_we_shouldn_t_trust_markets_with_our_civic_life |date=2015-05-21 }}. ]. Retrieved January 11, 2015.</ref> The economic historian ] was highly critical of the idea of the market-based society in his book '']'', stating that any attempt at its creation would undermine human society and the common good:<ref>Henry Farrell (July 18, 2014). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150915010202/http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/07/18/the-free-market-is-an-impossible-utopia/ |date=2015-09-15 }}. ''].'' Retrieved January 11, 2015.</ref> "Ultimately...the control of the economic system by the market is of overwhelming consequence to the whole organization of society; it means no less than the running of society as an adjunct to the market. Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Polanyi |first=Karl |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YfpIs1Z6B2sC |title=The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time |date=2001-03-28 |publisher=Beacon Press |isbn=978-0-8070-5642-4 |pages=60 |language=en |access-date=2023-01-04 |archive-date=2023-01-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230104145109/https://books.google.com/books?id=YfpIs1Z6B2sC&newbks=0&hl=en |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Another criticism is definitional, in that far-ranging governmental actions such as the creation of corporate personhood or more broadly, the governmental actions behind the very creation of artificial legal entities called corporations, are not considered "intervention" within mainstream economic schools. This inherent definitional bias allows many to advocate strong governmental actions that promote corporate power, while advocating against government actions limiting it, while putting these dual positions under the umbrella of "pro free markets" or "anti-intervention." | |||

| ] of the University of Houston argues in the Marxist tradition that the logic of the market inherently produces inequitable outcomes and leads to unequal exchanges, arguing that ]'s moral intent and moral philosophy espousing equal exchange was undermined by the practice of the free market he championed. According to McNally, the development of the ] involved coercion, exploitation and violence that Smith's moral philosophy could not countenance. McNally also criticizes market socialists for believing in the possibility of fair markets based on equal exchanges to be achieved by purging parasitical elements from the market economy such as ] of the ], arguing that ] is an oxymoron when ] is defined as an end to ].<ref>{{cite book|last=McNally|first=David|title=Against the Market: Political Economy, Market Socialism and the Marxist Critique|publisher=Verso|year=1993|isbn=978-0860916062}}</ref> | |||

| Critics of laissez-faire since ]<ref>"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices."--''Wealth of Nations'', I.x.c.27 (Part II)</ref> variously see the unregulated market as an impractical ideal or as a ] that puts the concepts of freedom and anti-] at the service of vested wealthy interests, allowing them to attack ]s and other protections of the ]es.<ref>"Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labour above their actual rate… masters… never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combinations of servants, labourers, and journeymen."--Adam Smith, ''Wealth of Nations'', I.viii.13</ref> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| Because no national economy in existence fully manifests the ideal of a free market as theorized by economists, some critics of the concept consider it to be a fantasy - outside of the bounds of reality in a complex system with opposing interests and different distributions of wealth. | |||

| {{Portal|Capitalism|Economics|Law|Libertarianism}} | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=22em}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| These critics range from those who reject markets entirely, in favour of a ] or a communal economy, such as that advocated by ], to those who merely wish to see ]s regulated to various degrees or supplemented by certain government interventions. For example, ] recognize a role for government in providing corrective measures, such as use of fiscal policy for economy stimulus, when decisions in the private sector lead to suboptimal economic outcomes, such as ] or ], which manifest in widespread hardship. | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| ===Externalities=== | |||

| {{refbegin|30em}} | |||

| One practical objection is the claim that markets do not take into account ] (effects of transactions that affect third parties), such as the negative effects of pollution or the positive effects of education. What exactly constitutes an externality may be up for debate, including the extent to which it changes based upon the political climate. | |||

| * ] “Excerpts from ‘About Free-Market Environmentalism.’” In Environment and Society: A Reader, edited by Christopher Schlottmann, Dale Jamieson, Colin Jerolmack, Anne Rademacher, and Maria Damon, 259–264. ], 2017. {{doi|10.2307/j.ctt1ht4vw6.38}}. | |||

| * Althammer, Jörg.<!-- He's listed in the Garman WP --> “Economic Efficiency and Solidarity: The Idea of a Social Market Economy.” Free Markets with Sustainability and Solidarity, edited by Martin Schlag and Juan A. Mercaso, ], 2016, pp. 199–216, {{doi|10.2307/j.ctt1d2dp8t.14}}. | |||

| Some proponents of market economies believe that governments should not diminish market freedom because they disagree on what is a market externality and what are government-created externalities, and disagree over what the appropriate level of intervention is necessary to solve market-created externalities. Others believe that government should intervene to prevent ] while preserving the general character of a market economy. In the model of a ] the state intervenes where the market does not meet political demands. ] was a prominent proponent of this idea. | |||

| * ]. “The Free Market Confronts Black Poverty.” The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, ], 2017, pp. 215–246, {{JSTOR|j.ctv24w649g.10}}. | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Barro, R.J.|title=Nothing is Sacred: Economic Ideas for the New Millennium|isbn=978-0262250511|series=The MIT Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TmLyGCJE-rIC|year=2003|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144733/https://books.google.com/books?id=TmLyGCJE-rIC|url-status=live}} | |||

| ===Differing Ideas of the Free Market=== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=]|title=Beyond the Invisible Hand: Groundwork for a New Economics|isbn=978-0691173696|lccn=2010012135|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n3CYDwAAQBAJ|year=2016|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144733/https://books.google.com/books?id=n3CYDwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||

| Some advocates of free market ideologies have criticized mainstream conceptions of the free market, arguing that a truly free market would not resemble the modern-day capitalist economy. For example, contemporary ] ] argues in favor of "free market anti-capitalism." Carson has stated that "From Smith to Ricardo and Mill, classical liberalism was a revolutionary doctrine that attacked the privileges of the great landlords and the mercantile interests. Today, we see vulgar libertarians perverting "free market" rhetoric to defend the contemporary institution that most closely resembles, in terms of power and privilege, the landed oligarchies and mercantilists of the Old Regime: the giant corporation." <ref>Kevin Carson, </ref> | |||

| * {{cite book|title=The Free-Market Innovation Machine: Analyzing the Growth Miracle of Capitalism|author=Baumol, William J.|author-link=William Baumol|isbn=978-1400851638|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tloXAwAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144734/https://books.google.com/books?id=tloXAwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||

| * ] and ] (2014). '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210429085412/https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674050716 |date=2021-04-29 }}.'' ]. {{ISBN|0674050711}}. {{JSTOR|j.ctt6wpr3f.7}}. | |||

| Carson believes that a true free market society would be " world in which... land and property widely distributed, capital freely available to laborers through mutual banks, productive technology freely available in every country without patents, and every people free to develop locally without colonial robbery..."<ref>Kevin Carson, </ref> | |||

| * Boettke, Peter J. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071201024600/http://www.the-dissident.com/Boettke_CR.pdf |date=2007-12-01 }}. | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |last=Boudreaux |first=Donald |author-link=Donald Boudreaux |editor-first=Ronald |editor-last=Hamowy |editor-link=Ronald Hamowy |encyclopedia=The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism |chapter=Free-Market Economy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yxNgXs3TkJYC |chapter-url=https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/libertarianism/n114.xml |year=2008 |publisher=]; ] |location=Thousand Oaks, CA |isbn=978-1412965804 |oclc=750831024 |lccn=2008009151 |pages=187–189 |title=Archived copy |access-date=2022-03-20 |archive-date=2023-01-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230109234738/https://books.google.com/books?id=yxNgXs3TkJYC |url-status=live }} | |||

| ===Martin J. Whitman=== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Burgin, A.|title=The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression|isbn=978-0674067431|lccn=2012015061|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BnZ1qKdXojoC|year=2012|publisher=Harvard University Press|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144735/https://books.google.com/books?id=BnZ1qKdXojoC|url-status=live}} | |||

| Not all advocates of ] consider free markets to be practical. For example, ] has written, in a discussion of ], ] and ], that these "…great economists…missed a lot of details that are part and parcel of every ]'s daily life." While calling Hayek "100% right" in his critique of the pure command economy, he writes "However, in no way does it follow, as many Hayek disciples seem to believe, that government is ''per se'' bad and unproductive while the private sector is, ''per se'' good and productive. In well-run industrial economies, there is a marriage between government and the private sector, each benefiting from the other." As illustrations of this, he points at "] after ], ] and the other ], ] and ]. The notable exception is ] which found prosperity on an extremely austere free market concept. | |||

| * ]. “Disrupting Free Market: State Capitalism and Social Distribution.” ''Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore'', ], 2017, pp. 98–122, {{JSTOR|10.7591/j.ctt1zkjz35.7}}. | |||

| * ] (2016). '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161111195435/http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674659681 |date=2016-11-11 }}.'' Harvard University Press. {{ISBN|978-0674659681}}. | |||

| He argues, in particular, for the value of government-provided credit and of carefully crafted tax laws.<ref name="iron4">Kevin Carson, , p. 4</ref> Further, Whitman argues (explicitly against Hayek) that "a free market situation is probably also doomed to failure if there exist control persons who are not subject to external disciplines imposed by various forces over and above competition." The lack of these disciplines, says Whitman, lead to "1. Very exorbitant levels of ]… 2. Poorly financed businesses with strong prospects for money defaults on credit instruments… 3. Speculative ]… 4. Tendency for industry competition to evolve into ] and ]… 5. Corruption." For all of these he provides recent examples from the U.S. economy, which he considers to be in some respects under-regulated,<ref name="iron4"/> although in other respects over-regulated (he is generally opposed to ]).<ref>Martin J. Whitman, (]), page 2.</ref> | |||

| * ] and Ronald Dekker. “Labour Arbitrage on European Labour Markets: Free Movement and the Role of Intermediaries.” ''Towards a Decent Labour Market for Low Waged Migrant Workers'', edited by Conny Rijken and Tesseltje de Lange, ], 2018, pp. 109–128, {{JSTOR|j.ctv6hp34j.7}}. | |||

| * {{cite book|author=de La Pradelle, M. and Jacobs, A. and Katz, J.|title=Market Day in Provence|isbn=978-0226141848|lccn=2005014063|series=Fieldwork Encounters And Discoveries, Ed. Robert Emerson And Jack Katz|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HHMlUcjfXPIC|year=2006|publisher=University of Chicago Press|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144736/https://books.google.com/books?id=HHMlUcjfXPIC|url-status=live}} | |||

| He believes that an apparently "free" relationship—that between a corporation and its investors and creditors—is actually a blend of "voluntary exchanges" and "coercion". For example, there are "voluntary activities, where each individual makes his or her own decision whether to buy, sell, or hold" but there are also what he defines as "oercive activities, where each individual security holder is forced to go along…provided that a requisite majority of other security holders so vote…" His examples of the latter include ], most merger and acquisition transactions, certain cash tender offers, and reorganization or liquidation in ].<ref>Martin J. Whitman, (]), page 5.</ref> Whitman also states that "] would not work at all unless many activities continued to be coercive."<ref>Martin J. Whitman, Third Avenue Value Fund letter to shareholders October 31, 2005. p.6.</ref> | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Eichner, M.|title=The Free-Market Family: How the Market Crushed the American Dream (and How It Can Be Restored)|isbn=978-0190055486|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9NjBDwAAQBAJ|year=2019|publisher=Oxford University Press|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144740/https://books.google.com/books?id=9NjBDwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Ferber, M.A. and Nelson, J.A.|title=Beyond Economic Man: Feminist Theory and Economics|isbn=978-0226242088|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BFg6lK48EX0C|year=2009|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144742/https://books.google.com/books?id=BFg6lK48EX0C|url-status=live}} | |||

| "I am one with Professor Friedman that, other things being equal, it is far preferable to conduct economic activities through voluntary exchange relying on free markets rather than through coercion. But Corporate America would not work at all unless many activities continued to be coercive."<ref>Martin J. Whitman, Third Avenue Value Fund letter to shareholders October 31, 2005. p.5-6.</ref> | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Fox, M.B. and Glosten, L. and Rauterberg, G.|title=The New Stock Market: Law, Economics, and Policy|isbn=978-0231543934|lccn=2018037234|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_oFbDwAAQBAJ|year=2019|publisher=]|access-date=2022-10-24|archive-date=2022-10-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221024235604/https://books.google.com/books?id=_oFbDwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=] and ]|title=Capitalism and Freedom|isbn=978-0226264011|lccn=62019619|series=Phoenix Book : business/economics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CE49HAiRugAC|year=1962|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118144746/https://books.google.com/books?id=CE49HAiRugAC|url-status=live}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Garrett, G. and Bates, R.H. and Comisso, E. and Migdal, J. and Lange, P. and Milner, H.|title=Partisan Politics in the Global Economy|isbn=978-0521446907|lccn=97016731|series=Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RoePU0zM7t4C|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145248/https://books.google.com/books?id=RoePU0zM7t4C|url-status=live}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Group of Lisbon Staff and Cara, J.|title=Limits to Competition|isbn=978-0262071642|lccn=95021461|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2OT8IsbJubsC|year=1995|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145247/https://books.google.com/books?id=2OT8IsbJubsC|url-status=live}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Harcourt, Bernard E.|author-link=Bernard Harcourt|title=The Illusion of Free Markets: Punishment and the Myth of Natural Order|isbn=978-0674059368|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-nYLSvgP2ekC|year=2011|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145248/https://books.google.com/books?id=-nYLSvgP2ekC|url-status=live}} | |||

| *'']'' | |||

| * ] (1948). ''Individualism and Economic Order''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. vii, 271, . | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|author1=Helleiner, Eric|author1-link=Eric Helleiner|author2=Pickel, Andreas|title=Economic Nationalism in a Globalizing World|isbn=978-0801489662|lccn=2004015590|series=Cornell studies in political economy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oCpor-DkFwwC|year=2005|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145248/https://books.google.com/books?id=oCpor-DkFwwC|url-status=live}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * Higgs, Kerryn. “The Rise of Free Market Fundamentalism.” Collision Course: Endless Growth on a Finite Planet, ], 2014, pp. 79–104, {{JSTOR|j.ctt9qf93v.11}}. | |||

| *] | |||

| * Holland, Eugene W. “Free-Market Communism.” Nomad Citizenship: Free-Market Communism and the Slow-Motion General Strike, NED-New edition, ], 2011, pp. 99–140, {{JSTOR|10.5749/j.ctttsw4g.8}}. | |||

| *] | |||

| * Hoopes, James. “Corporations as Enemies of the Free Market.” Corporate Dreams: Big Business in American Democracy from the Great Depression to the Great Recession, ], 2011, pp. 27–32, {{JSTOR|j.ctt5hjgkf.8}}. | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Howell, D.R.|title=Fighting Unemployment: The Limits of Free Market Orthodoxy|isbn=978-0195165852|lccn=2004049283|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PHs8DwAAQBAJ|year=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145249/https://books.google.com/books?id=PHs8DwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * Jónsson, Örn D., and Rögnvaldur J. Sæmundsson. “Free Market Ideology, Crony Capitalism, and Social Resilience.” Gambling Debt: Iceland's Rise and Fall in the Global Economy, edited by E. Paul Durrenberger and Gisli Palsson, ], 2015, pp. 23–32, {{JSTOR|j.ctt169wdcd.8}}. | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Kuhner, T.K.|title=Capitalism v. Democracy: Money in Politics and the Free Market Constitution|isbn=978-0804791588|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ljaOAwAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=]|access-date=2022-03-11|archive-date=2023-01-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230118145252/https://books.google.com/books?id=ljaOAwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}} | |||