| Revision as of 14:30, 26 January 2010 editClueBot (talk | contribs)1,596,818 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 169.244.58.98 to version by Catgut. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (534578) (Bot)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:48, 14 January 2025 edit undoOAbot (talk | contribs)Bots442,414 editsm Open access bot: doi updated in citation with #oabot. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Type of eating disorder}} | |||

| {{otheruses6|Anorexia nervosa (disambiguation)|Anorexia}} | |||

| {{redirect2|Anorexia|Anorexic|lack of appetite|Anorexia (symptom)|the medication|Anorectic|other uses|Anorexia (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Infobox_Disease | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} | |||

| | Name = Anorexia Nervosa | |||

| {{cs1 config |name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| | Image = | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

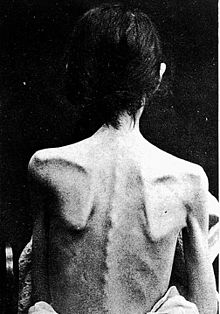

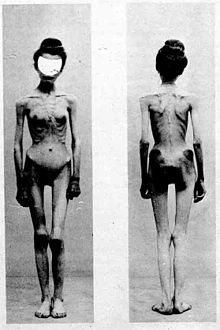

| | Caption = A female with anorexia | |||

| | name = Anorexia nervosa | |||

| | DiseasesDB = 749 | |||

| | synonym = Anorexia, AN | |||

| | ICD10 = {{ICD10|F|50|0|f|50}}-{{ICD10|F|50|1|f|50}} | |||

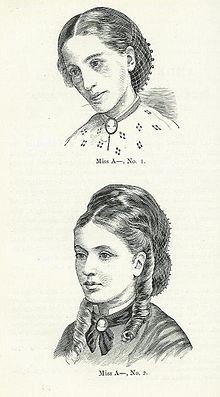

| | image = Gull - Anorexia Miss A.jpg | |||

| | ICD9 = {{ICD9|307.1}} | |||

| | caption = "Miss A—" depicted in 1866 and in 1870 after treatment. Her condition was one of the earliest case studies of anorexia, published in medical research papers of ]. | |||

| | ICDO = | |||

| | field = ], ] | |||

| | OMIM = 606788 | |||

| | symptoms = Fear of gaining weight, strong desire to be thin, ]s,<ref name=NIH2015 /> ] | |||

| | MedlinePlus = | |||

| | complications = ], ], heart damage, ],<ref name=NIH2015/> whole-body swelling (]), ] and/or ], gastrointestinal problems, extensive muscle weakness, ], death<ref>{{cite web|title=Anorexia Nervosa |url=https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9794-anorexia-nervosa |website=My.clevelandclinic.org|access-date=9 June 2022}}</ref> | |||

| | eMedicineSubj = emerg | |||

| | onset = Adolescence to early adulthood<ref name=NIH2015 /> | |||

| | eMedicineTopic = 34 | |||

| | duration = | |||

| | eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|med|144}} | |||

| | causes = Unknown<ref | |||

| | MeshID = | |||

| name="Attia_2010" /> | |||

| | risks = Family history, high-level athletics, ], ], ], ], being a ] or ]<ref name="Attia_2010"/><ref name=DSM5book/><ref name="Arcelus_2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Arcelus J, Witcomb GL, Mitchell A | title = Prevalence of eating disorders amongst dancers: a systemic review and meta-analysis | journal = European Eating Disorders Review | volume = 22 | issue = 2 | pages = 92–101 | date = March 2014 | pmid = 24277724 | doi = 10.1002/erv.2271 | url = https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/erv.2271}}</ref> | |||

| | diagnosis = | |||

| | differential = ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Parker R, Sharma A |title=General Medicine|date=2008 |publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences |isbn=978-0-7234-3461-0 |page=56 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qpeIXuCPgAwC&pg=PA56 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| vauthors = First MB |title=DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SqeTAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA248|publisher=American Psychiatric Pub|date=19 November 2013|isbn=978-1-58562-462-1|via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = ], hospitalisation to restore weight<ref name=NIH2015 /><ref name=DSM5 /> | |||

| | medication = | |||

| | prognosis = 5% risk of death over 10 years<ref name=DSM5book/><ref name="Espie_2015" /> | |||

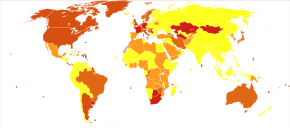

| | frequency = 2.9 million (2015)<ref name=GBD2015Pre>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, etal | title = Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1545–1602 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733282 | pmc = 5055577 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 | collaboration = GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators | issn=0140-6736}}</ref> | |||

| | deaths = 600 (2015)<ref name=GBD2015De>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, etal | title = Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1459–1544 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733281 | pmc = 5388903 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 | collaboration = GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators }}</ref> | |||

| | alt = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Anorexia nervosa''' is an ] characterized by extremely low ], distorted ] and an obsessive fear of gaining weight. <ref>http://www.psychiatryonline.com/content.aspx?aID=3617&searchStr=anorexia+nervosa</ref> | |||

| <!-- Definition and symptoms --> | |||

| The term anorexia nervosa was established in 1873 by ], one of ]'s personal physicians.<ref>Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica) (1873) William Withey Gull, published in the 'Clinical Society's Transactions, vol vii, 1874, p22</ref> The term is of Greek origin: ''a'' (α, prefix of negation), ''n'' (ν, link between two vowels) and ''orexis'' (ορεξις, appetite), thus meaning a lack of desire to eat.<ref>{{cite book |last=Costin |first=Carolyn |year=1999 |title=The Eating Disorder Sourcebook |location=Linconwood |publisher=Lowell House |page=6 |isbn=0585189226}}</ref> | |||

| '''Anorexia nervosa''' ('''AN'''), often referred to simply as '''anorexia''',<ref name="Treasure_2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Treasure J, Zipfel S, Micali N, Wade T, Stice E, Claudino A, Schmidt U, Frank GK, Bulik CM, Wentz E | title = Anorexia nervosa | journal = Nature Reviews. Disease Primers | volume = 1 | pages = 15074 | date = November 2015 | pmid = 27189821 | doi = 10.1038/nrdp.2015.74 | s2cid = 21580134 }}</ref> is an ] characterized by ], ], fear of gaining weight, and an overpowering desire to be thin.<ref name=NIH2015 /> | |||

| Individuals with anorexia nervosa have a fear of being ] or being seen as such, despite the fact that they are typically ].<ref name="NIH2015" /><ref name="Attia_2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Attia E | title = Anorexia nervosa: current status and future directions | journal = Annual Review of Medicine | volume = 61 | issue = 1 | pages = 425–435 | year = 2010 | pmid = 19719398 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.med.050208.200745 }}</ref> The DSM-5 describes this perceptual symptom as "disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced".<ref name="DSM5" /> In ] and clinical settings, this symptom is called "body image disturbance"<ref name="Artoni_2021">{{cite journal | vauthors = Artoni P, Chierici ML, Arnone F, Cigarini C, De Bernardis E, Galeazzi GM, Minneci DG, Scita F, Turrini G, De Bernardis M, Pingani L | title = Body perception treatment, a possible way to treat body image disturbance in eating disorders: a case-control efficacy study | journal = Eating and Weight Disorders | volume = 26 | issue = 2 | pages = 499–514 | date = March 2021 | pmid = 32124409 | doi = 10.1007/s40519-020-00875-x | s2cid = 211728899 }}</ref> or ]. Individuals with anorexia nervosa also often deny that they have a problem with low weight<ref name="DSM5book">{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/diagnosticstatis0005unse/page/338 |title=Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 |date=2013 |publisher=American Psychiatric Publishing |isbn=978-0-89042-555-8 |edition=5th |location=Washington |pages=}}</ref> due to their altered perception of appearance. They may weigh themselves frequently, eat small amounts, and only eat certain foods.<ref name="NIH2015" /> Some patients with anorexia nervosa ] and ] to influence their weight or shape.<ref name="NIH2015" /> Purging can be defined by excessive exercise, induced ], and/or ] abuse. Medical complications may include ], ], and heart damage,<ref name="NIH2015">{{cite web|title=What are Eating Disorders?|url=http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml|website=NIMH|access-date=24 May 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150523184510/http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml|archive-date=23 May 2015}}</ref> along with the ].<ref name="DSM5book" /> In cases where the patients with anorexia nervosa continually refuse significant dietary intake and weight restoration interventions, a psychiatrist can declare the patient to lack capacity to make decisions. Then, these patients' medical proxies<ref>{{Cite web |title=Proxy definition and meaning |url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/proxy |access-date=2020-10-02 |work=Collins English Dictionary |language=en}}</ref> decide that the patient needs to be fed by ] via ]<ref name="Kodua_2020" /> <ref>{{Cite web|title=Force-Feeding of Anorexic Patients and the Right to Die|url=http://www.mdmc-law.com/tasks/sites/mdmc/assets/Image/MDAdvisor_Fall2017_Jackson.pdf|access-date=2 October 2020|archive-date=23 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201123231259/http://www.mdmc-law.com/tasks/sites/mdmc/assets/Image/MDAdvisor_Fall2017_Jackson.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref><!-- Cause and diagnosis --> | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| A definition of anorexia nervosa was established by the ] (DSM-IV-TR) and the ] ] (ICD). | |||

| Anorexia often develops during adolescence or young adulthood.<ref name=NIH2015 /> The main origins of anorexia nervosa rest primarily in sexual abuse and problematic familial relations, especially those of overprotecting parents showing excessive possessiveness over their children.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Matt Lacoste |first=S. |date=2017-09-01 |title=Looking for the origins of anorexia nervosa in adolescence - A new treatment approach |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1359178916301768 |journal=Aggression and Violent Behavior |volume=36 |pages=76–80 |doi=10.1016/j.avb.2017.07.006 |issn=1359-1789}}</ref> The exacerbations of the mental illness are thought to follow a major life-change or ]-inducing events.<ref name=DSM5book /> The causes of anorexia are varied and may differ from individual to individual.<ref name="Attia_2010" /> There is emerging evidence that there is a ] component, with ] more often affected than fraternal twins.<ref name="Attia_2010" /> Cultural factors also appear to play a role, with societies that value thinness having higher rates of the disease.<ref name=DSM5book /> Anorexia also commonly occurs in athletes who play sports where a low bodyweight is thought to be advantageous for aesthetics or performance, such as dance, ], running, and ].<ref name=DSM5book /><ref name="Arcelus_2014" /><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.019| title = Anorexia athletica| date = 2004| journal = Nutrition| volume = 20| issue = 7–8| pages = 657–661| pmid = 15212748| vauthors = Sudi K, Öttl K, Payerl D, Baumgartl P, Tauschmann K, Müller W }}</ref> | |||

| DSM-IV-TR criteria are: | |||

| *Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g. weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight less than 85% of that expected; or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85% of that expected). | |||

| *Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. | |||

| *Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight. | |||

| *Amenorrhea (at least three consecutive cycles) in postmenarchal girls and women. Amenorrhea is defined as periods occurring only following hormone (e.g., estrogen) administration. | |||

| <!-- Prevention, treatment and prognosis --> | |||

| Furthermore, the DSM-IV-TR specifies two subtypes: | |||

| Treatment of anorexia involves restoring the patient back to a healthy weight, treating their underlying psychological problems, and addressing underlying maladaptive behaviors.<ref name=NIH2015 /> A daily low dose of ] (Zyprexa®, Eli Lilly) has been shown to increase appetite and assist with weight gain in anorexia nervosa patients.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Walsh |first=Timothy |title=Eating Disorders: What Everyone Needs to Know |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2020 |isbn=978-0190926595 |pages=105–113 |language=English}}</ref> Psychiatrists may prescribe their anorexia nervosa patients medications to better manage their ] or ].<ref name=NIH2015 /> Different therapy methods may be useful, such as ] or an approach where parents assume responsibility for feeding their child, known as ].<ref name=NIH2015 /><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hay P |title=A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012 |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=46 |issue=5 |pages=462–469 |date=July 2013 |pmid=23658093 |doi=10.1002/eat.22103}}</ref> Sometimes people require admission to a hospital to restore weight.<ref name=DSM5 /> Evidence for benefit from ] feeding is unclear.<ref name="NICE2004">{{cite news |date=2004 |title=Eating Disorders: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and Related Eating Disorders |pages=103 |pmid=23346610}}</ref> Such an intervention may be highly distressing for both anorexia patients and healthcare staff when administered against the patient's will under restraint.<ref name="Kodua_2020">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kodua M, Mackenzie JM, Smyth N |title=Nursing assistants' experiences of administering manual restraint for compulsory nasogastric feeding of young persons with anorexia nervosa |journal=International Journal of Mental Health Nursing |volume=29 |issue=6 |pages=1181–1191 |date=December 2020 |pmid=32578949 |doi=10.1111/inm.12758 |s2cid=220046454 |url=https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/qzxqv/nursing-assistants-experiences-of-administering-manual-restraint-for-compulsory-nasogastric-feeding-of-young-persons-with-anorexia-nervosa}}</ref> Some people with anorexia will have a single episode and recover while others may have recurring episodes over years.<ref name=DSM5 /> The largest risk of ] occurs within the first year post-discharge from eating disorder therapy treatment. Within the first 2 years post-discharge from eating disorder treatment, approximately 31% of anorexia nervosa patients relapse.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Berends |first=Tamara |title=Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. |journal=Current Opinion in Psychiatry |date=2018 |volume=31 |issue=6 |pages=445–455 |doi=10.1097/YCO.0000000000000453 |pmid=30113325 |hdl=1874/389359 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> Many complications, both physical and psychological, improve or resolve with nutritional rehabilitation and adequate weight gain.<ref name=DSM5 /> | |||

| * ''Restricting Type'': during the current episode of anorexia nervosa, the person has not regularly engaged in ] or purging behavior (that is, self-induced vomiting, or the misuse of ]s, ]s, or ]s). Weight loss is accomplished primarily through dieting, ], or excessive exercise. | |||

| * ''Binge-Eating Type or Purging Type'': during the current episode of anorexia nervosa, the person has regularly engaged in binge-eating OR purging behavior (that is, self-induced vomiting, or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas). | |||

| <!-- Epidemiology prognosis --> | |||

| The ] criteria are similar, but in addition, specifically mention | |||

| It is estimated to occur in 0.3% to 4.3% of women and 0.2% to 1% of men in Western countries at some point in their life.<ref name="Smink_2012">{{cite journal |vauthors=Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW |title=Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates |journal=Current Psychiatry Reports |volume=14 |issue=4 |pages=406–414 |date=August 2012 |pmid=22644309 |pmc=3409365 |doi=10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y}}</ref> About 0.4% of young women are affected in a given year and it is estimated to occur ten times more commonly among women than men.<ref name=DSM5book /><ref name="Smink_2012" /> It is unclear whether the increased incidence of anorexia observed in the 20th and 21st centuries is due to an actual increase in its frequency or simply due to improved diagnostic capabilities.<ref name="Attia_2010" /> In 2013, it directly resulted in about 600 deaths globally, up from 400 deaths in 1990.<ref name=GDB2013>{{cite journal |vauthors=Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, etal |title=Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 |journal=Lancet |volume=385 |issue=9963 |pages=117–171 |date=January 2015 |pmid=25530442 |pmc=4340604 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 |collaboration=GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators }}</ref> Eating disorders also increase a person's risk of death from a wide range of other causes, including ].<ref name=NIH2015 /><ref name="Smink_2012" /> About 5% of people with anorexia die from complications over a ten-year period<ref name=DSM5book /><ref name="Espie_2015" /> with medical complications and suicide being the primary and secondary causes of death respectively.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=April R |last2=Zuromski |first2=Kelly L |last3=Dodd |first3=Dorian R |date=2018-08-01 |title=Eating disorders and suicidality: what we know, what we don't know, and suggestions for future research |url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2352250X17301859 |journal=Current Opinion in Psychology |series=Suicide |volume=22 |pages=63–67 |doi=10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.023 |pmid=28846874 |issn=2352-250X}}</ref> | |||

| # The ways that individuals might induce weight-loss or maintain low body weight (avoiding fattening foods, self-induced vomiting, self-induced purging, excessive exercise, excessive use of appetite suppressants or diuretics). | |||

| # Certain physiological features, including ''"widespread ] disorder involving ]-]-]al axis is manifest in women as ] and in men as loss of sexual interest and potency. There may also be elevated levels of ]s, raised ] levels, changes in the peripheral ] of ] hormone and abnormalities of insulin secretion"''. | |||

| # If onset is before puberty, that development is delayed or arrested. | |||

| == Signs and symptoms == | |||

| The distinction between the diagnoses of anorexia nervosa, ] and ] (EDNOS) is often difficult to make in practice and there is considerable overlap between patients diagnosed with these conditions. Furthermore, seemingly minor changes in a patient's overall behavior or attitude can change a diagnosis from "anorexia: binge-eating type" to bulimia nervosa. It is not unusual for a person with an eating disorder to "move through" various diagnoses as his or her behavior and beliefs change over time.<ref name=Zucker1>{{Cite journal | volume = 133 | issue = 6 | pages = 976–1006 | last = Zucker | first = N. L | coauthors = M. Losh, C. M Bulik, K. S LaBar, J. Piven, K. A Pelphrey | title = Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: Guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes | journal = Psychological Bulletin | date = 2007 | url = http://www.duke.edu/web/mind/level2/faculty/labar/pdfs/Zucker_et_al_2007.pdf | doi = 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976 | pmid = 17967091}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by attempts to lose weight by way of ]. A person with anorexia nervosa may exhibit a number of signs and symptoms, the type and severity of which may vary and be present but not readily apparent.<ref name="Surgenor_2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Surgenor LJ, Maguire S | title = Assessment of anorexia nervosa: an overview of universal issues and contextual challenges | journal = Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 29 | year = 2013 | pmid = 24999408 | pmc = 4081667 | doi = 10.1186/2050-2974-1-29 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Though anorexia is typically recognized by the physical manifestations of the illness, it is a mental disorder that can be present at any weight. | |||

| Anorexia nervosa, and the associated ] that results from self-imposed starvation, can cause ] in every major ] in the body.<ref name="Strumia_2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Strumia R | title = Skin signs in anorexia nervosa | journal = Dermato-Endocrinology | volume = 1 | issue = 5 | pages = 268–270 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 20808514 | pmc = 2836432 | doi = 10.4161/derm.1.5.10193 }}</ref> ], a drop in the level of potassium in the blood, is a sign of anorexia nervosa.<ref name="Miller_2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Miller KK | title = Endocrine effects of anorexia nervosa | journal = Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America | volume = 42 | issue = 3 | pages = 515–528 | date = September 2013 | pmid = 24011884 | pmc = 3769686 | doi = 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.007 }}</ref><ref name="Walsh_2000">{{cite journal | vauthors = Walsh JM, Wheat ME, Freund K | title = Detection, evaluation, and treatment of eating disorders the role of the primary care physician | journal = Journal of General Internal Medicine | volume = 15 | issue = 8 | pages = 577–590 | date = August 2000 | pmid = 10940151 | pmc = 1495575 | doi = 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02439.x }}</ref> A significant drop in potassium can cause ], ], fatigue, muscle damage, and ].<ref>{{Cite book|title = Herb, Nutrient, and Drug Interactions: Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Strategies|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=49kLK--eumEC&q=potassium%20decreased%20arrhythmia&pg=PA585|publisher = Elsevier Health Sciences|date = 2008|access-date = 9 April 2015|isbn = 978-0-323-02964-3|vauthors=Stargrove MB, Treasure J, McKee DL }}</ref> | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| ====Genetics==== | |||

| Family and ] have suggested that genetic and environmental factors account for 74% and 26% of the ] in anorexia nervosa, respectively.<ref name="Klump2001">{{cite journal |author=Klump KL, Miller KB, Keel PK, McGue M, Iacono WG |title=Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population-based twin sample |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=31 |issue=4 |pages=737–40 |year=2001 |month=May |pmid=11352375 |doi=10.1017/S0033291701003725}}</ref> This evidence suggests that genes influencing both eating regulation, and personality and emotion, may be important contributing factors. In one study, variations in the ] gene ] were associated with restrictive anorexia nervosa, but not binge-purge anorexia (though the latter may have been due to small sample size).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Urwin RE, Bennetts B, Wilcken B, ''et al.'' |title=Anorexia nervosa (restrictive subtype) is associated with a polymorphism in the novel norepinephrine transporter gene promoter polymorphic region |journal=Molecular Psychiatry |volume=7 |issue=6 |pages=652–7 |year=2002 |pmid=12140790 |doi=10.1038/sj.mp.4001080}}</ref> | |||

| Signs and symptoms may be classified in various categories including: physical, cognitive, affective, behavioral and perceptual: | |||

| ====Neurobiological==== | |||

| Anorexia may be linked to a disturbed serotonin system,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kaye WH, Frank GK, Bailer UF, ''et al.'' |title=Serotonin alterations in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: new insights from imaging studies |journal=Physiology & Behavior |volume=85 |issue=1 |pages=73–81 |year=2005 |month=May |pmid=15869768 |doi=10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.013}}</ref> particularly to high levels at areas in the brain with the ] - a system particularly linked to ], ] and ]. Starvation has been hypothesised to be a response to these effects, as it is known to lower ] and ] metabolism, which might reduce serotonin levels at these critical sites and ward off anxiety. Other studies of the 5HT<sub>2A</sub> serotonin receptor (linked to regulation of feeding, mood, and anxiety), suggest that serotonin activity is decreased at these sites. There is evidence that both personality characteristics and disturbances to the serotonin system are still apparent after patients have recovered from anorexia.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kaye WH, Bailer UF, Frank GK, Wagner A, Henry SE |title=Brain imaging of serotonin after recovery from anorexia and bulimia nervosa |journal=Physiology & Behavior |volume=86 |issue=1-2 |pages=15–7 |year=2005 |month=September |pmid=16102788 |doi=10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.019}}</ref> | |||

| === Physical symptoms === | |||

| Changes in brain structure and function are early signs often to be associated with ], and is partially reversed when normal weight is regained.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Palazidou E, Robinson P, Lishman WA |title=Neuroradiological and neuropsychological assessment in anorexia nervosa |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=20 |issue=3 |pages=521–7 |year=1990 |month=August |pmid=2236361 |doi=10.1017/S0033291700017037}}</ref> Anorexia is also linked to reduced blood flow in the ]s. It is possible that it is a risk trait rather than an effect of starvation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lask B, Gordon I, Christie D, Frampton I, Chowdhury U, Watkins B |title=Functional neuroimaging in early-onset anorexia nervosa |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=37 Suppl |issue= |pages=S49–51; discussion S87–9 |year=2005 |pmid=15852320 |doi=10.1002/eat.20117}}</ref> | |||

| * A low ] for one's age and height (except in cases of "atypical anorexia")<ref>{{cite book |title=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |date=2013-05-22 |publisher=American Psychiatric Association |isbn=978-0-89042-555-8 |page=339 |edition=5th |doi=10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 |url=https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 |access-date=2024-02-29 | last = American Psychiatric Association }}</ref> | |||

| * Rapid, continuous ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Anorexia Nervosa |url=http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140413130141/http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/ |archive-date=13 April 2014 |access-date=15 April 2014 |publisher=National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders}}</ref> | |||

| * Dry hair and skin, hair thinning, as well as ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Mehler |first1=Philip S. |last2=Brown |first2=Carrie |date=2015-03-31 |title=Anorexia nervosa – medical complications |journal=Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=11 |doi=10.1186/s40337-015-0040-8 |doi-access=free |issn=2050-2974 |pmc=4381361 |pmid=25834735}}</ref> | |||

| * Feeling cold all the time (])<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Smith |first=Lucille Lakier |date=2021-08-06 |title=The Central Role of Hypothermia and Hyperactivity in Anorexia Nervosa: A Hypothesis |journal=Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience |volume=15 |doi=10.3389/fnbeh.2021.700645 |doi-access=free |issn=1662-5153 |pmc=8377352 |pmid=34421554}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sirufo |first1=Maria Maddalena |last2=Ginaldi |first2=Lia |last3=De Martinis |first3=Massimo |date=2021-05-10 |title=Peripheral Vascular Abnormalities in Anorexia Nervosa: A Psycho-Neuro-Immune-Metabolic Connection |journal=International Journal of Molecular Sciences |language=en |volume=22 |issue=9 |pages=5043 |doi=10.3390/ijms22095043 |doi-access=free |issn=1422-0067 |pmc=8126077 |pmid=34068698}}</ref> | |||

| * ] or ] | |||

| * ] or ] | |||

| * ]<ref name="Nolen_2013">{{Cite book |title=Abnormal Psychology |vauthors=Nolen-Hoeksema S |publisher=McGraw Hill |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-07-803538-8 |location=New York |pages=339–41}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Having severe ], aches and pains | |||

| * Irregular or ] ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Poyastro Pinheiro |first1=Andréa |last2=Thornton |first2=Laura M. |last3=Plotonicov |first3=Katherine H. |last4=Tozzi |first4=Federica |last5=Klump |first5=Kelly L. |last6=Berrettini |first6=Wade H. |last7=Brandt |first7=Harry |last8=Crawford |first8=Steven |last9=Crow |first9=Scott |last10=Fichter |first10=Manfred M. |last11=Goldman |first11=David |last12=Halmi |first12=Katherine A. |last13=Johnson |first13=Craig |last14=Kaplan |first14=Allan S. |last15=Keel |first15=Pamela |date=July 2007 |title=Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=40 |issue=5 |pages=424–434 |doi=10.1002/eat.20388 |issn=0276-3478 |pmid=17497704}}</ref> periods | |||

| * Infertility | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Hedrick T |title=The Overlap Between Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Disorders |website=Nutrition issues in Gastroenterology |publisher=University of Virginia|date=August 2022|url=https://med.virginia.edu/ginutrition/wp-content/uploads/sites/199/2022/08/August-2022-Eating-Disorders-and-GI-Disorders.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240208022520/https://med.virginia.edu/ginutrition/wp-content/uploads/sites/199/2022/08/August-2022-Eating-Disorders-and-GI-Disorders.pdf|archive-date=2024-02-08}}</ref> | |||

| * ] (from vomiting or starvation-induced ]) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]; can be a tell-tale sign of self-induced vomiting with scratches on the back of the hand | |||

| * Tooth erosion<ref name="Bern_2013" /> | |||

| * ]: soft, fine hair growing over the face and body<ref name="Walsh2">{{cite journal |vauthors=Walsh JM, Wheat ME, Freund K |date=August 2000 |title=Detection, evaluation, and treatment of eating disorders the role of the primary care physician |journal=Journal of General Internal Medicine |volume=15 |issue=8 |pages=577–590 |doi=10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02439.x |pmc=1495575 |pmid=10940151}}</ref> | |||

| * Orange discoloration of the skin, particularly the feet (]) | |||

| === Cognitive symptoms === | |||

| Anorexia may be linked to an autoimmune response to ] ] which influence appetite and stress responses.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Fetissov SO, Harro J, Jaanisk M, ''et al.'' |title=Autoantibodies against neuropeptides are associated with psychological traits in eating disorders |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=102 |issue=41 |pages=14865–70 |year=2005 |month=October |pmid=16195379 |pmc=1253594 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0507204102}}</ref> | |||

| * An ] with counting calories and monitoring contents of food | |||

| * Preoccupation with food, recipes, or cooking; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves or consume a very small portion | |||

| * Admiration of thinner people | |||

| * Thoughts of being fat or not thin enough<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Walsh |first=B. Timothy |date=May 2013 |title=The Enigmatic Persistence of Anorexia Nervosa |journal=American Journal of Psychiatry |volume=170 |issue=5 |pages=477–484 |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12081074 |issn=0002-953X |pmc=4095887 |pmid=23429750}}</ref> | |||

| * An altered mental representation of one's body | |||

| * Impaired ], exacerbated by lower BMI and depression<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bora E, Köse S | title = Meta-analysis of theory of mind in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A specific İmpairment of cognitive perspective taking in anorexia nervosa? | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 49 | issue = 8 | pages = 739–740 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 27425037 | doi = 10.1002/eat.22572 | hdl = 11343/291969 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Difficulty in abstract thinking and problem solving | |||

| * Rigid and inflexible thinking | |||

| * Poor ] | |||

| * Hypercriticism and ] | |||

| === |

=== Affective symptoms === | ||

| * ] | |||

| ] deficiency may play a role in Anorexia. It is not thought responsible for causation of the initial illness but there is evidence that it may be an accelerating factor that deepens the pathology of the anorexia. A 1994 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that zinc (14 mg per day) doubled the rate of body mass increase compared to patients receiving the placebo.<ref name="Zincappetitereview">{{cite journal |author=Shay NF, Mangian HF |title=Neurobiology of zinc-influenced eating behavior |journal=The Journal of Nutrition |volume=130 |issue=5S Suppl |pages=1493S–9S |year=2000 |month=May |pmid=10801965 |url=http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10801965}}</ref> | |||

| * Ashamed of oneself or one's body | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Rapid ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| === |

=== Behavioral symptoms === | ||

| * Compulsive weighing | |||

| * Regular body checking | |||

| * Food restriction, both in terms of caloric content and type (for example, ] groups) | |||

| * Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces and measuring it, refusing to eat around others, and hiding or discarding of food | |||

| * Purging, which may be achieved through self-induced vomiting, ], ], ], ], or exercise. The goals of purging are various, including the prevention of weight gain, discomfort with the physical sensation of being full or bloated, and feelings of guilt or impurity.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2017-08-23 |title=Anorexia nervosa |url=https://nedc.com.au/eating-disorders/eating-disorders-explained/types/anorexia-nervosa/ |access-date=2022-09-19 | work = National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) |language= en-AU }}</ref> | |||

| * Excessive exercise<ref name="Marzola_2013">{{cite journal |vauthors=Marzola E, Nasser JA, Hashim SA, Shih PA, Kaye WH |date=November 2013 |title=Nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa: review of the literature and implications for treatment |journal=BMC Psychiatry |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=290 |doi=10.1186/1471-244X-13-290 |pmc=3829207 |pmid=24200367 |doi-access=free }}</ref> or compulsive movement,<ref>{{cite book |title=Community treatment of eating disorders |vauthors=Robinson PH |date=2006 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-0-470-01676-3 |location=Chichester |page=66}}</ref> such as pacing. | |||

| * ] or self-loathing | |||

| * Social withdrawal and ], stemming from the avoidance of friends, family, and events where food may be present | |||

| * Excessive water consumption to create a false impression of ] | |||

| * Excessive ] consumption | |||

| === Perceptual symptoms === | |||

| Anorexic eating behavior is thought to originate from an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rosen JC, Reiter J, Orosan P |title=Assessment of body image in eating disorders with the body dysmorphic disorder examination |journal=Behaviour Research and Therapy |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=77–84 |year=1995 |month=January |pmid=7872941 |doi=10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0030-M}}</ref> and is maintained by various ]es that alter how the affected individual evaluates and thinks about their body, food and eating. This is not a ] problem, but one of how the perceptual information is evaluated by the affected person.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Skrzypek S, Wehmeier PM, Remschmidt H |title=Body image assessment using body size estimation in recent studies on anorexia nervosa. A brief review |journal=European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=215–21 |year=2001 |month=December |pmid=11794546 |doi=10.1007/s007870170010}}</ref> People with anorexia nervosa seem to more accurately judge their own body image while lacking a self-esteem boosting bias.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Jansen A, Smeets T, Martijn C, Nederkoorn C |title=I see what you see: the lack of a self-serving body-image bias in eating disorders |journal=The British Journal of Clinical Psychology / the British Psychological Society |volume=45 |issue=Pt 1 |pages=123–35 |year=2006 |month=March |pmid=16480571 |doi=10.1348/014466505X50167}}</ref> | |||

| * Perception that one is not sick (]) or not sick "enough,"<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gaudiani |first=Jennifer |title=Sick Enough: A Guide to the Medical Complications of Eating Disorders |date=October 2, 2018 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0815382454 |edition=1st}}</ref> which may prevent some from seeking recovery | |||

| * Perception of self as heavier or fatter than in reality, ie. ]<ref name="Artoni_2021" /> | |||

| * Altered body schema, ie. a distorted and unconscious perception of one's body size and shape that influences how the individual experiences their body during physical activities. For example, a patient with anorexia nervosa may genuinely fear that they cannot fit through a narrow passageway. However, due to their malnourished state, their body is significantly smaller than someone with a normal BMI who would actually struggle to fit through the same space. In spite of having a small frame, the patient's altered body schema leads them to perceive their body as larger than it is. | |||

| * Altered ] | |||

| === Interoception === | |||

| People with anorexia nervosa also have other psychological difficulties and ]. ], ], ] and one or more ] may be the most likely conditions to be ] with anorexia. High-levels of anxiety and depression are likely to be present regardless of whether they fulfill diagnostic criteria for a specific syndrome.<ref>{{cite journal |author=O'Brien KM, Vincent NK |title=Psychiatric comorbidity in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: nature, prevalence, and causal relationships |journal=Clinical Psychology Review |volume=23 |issue=1 |pages=57–74 |year=2003 |month=February |pmid=12559994 |doi=10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00201-5}}</ref> | |||

| ] involves the conscious and unconscious sense of the internal state of the body, and it has an important role in ] and regulation of emotions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Khalsa SS, Adolphs R, Cameron OG, Critchley HD, Davenport PW, Feinstein JS, Feusner JD, Garfinkel SN, Lane RD, Mehling WE, Meuret AE, Nemeroff CB, Oppenheimer S, Petzschner FH, Pollatos O, Rhudy JL, Schramm LP, Simmons WK, Stein MB, Stephan KE, Van den Bergh O, Van Diest I, von Leupoldt A, Paulus MP | title = Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap | journal = Biological Psychiatry. Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging | volume = 3 | issue = 6 | pages = 501–513 | date = June 2018 | pmid = 29884281 | pmc = 6054486 | doi = 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004 }}</ref> Aside from noticeable physiological dysfunction, interoceptive deficits also prompt individuals with anorexia to concentrate on distorted perceptions of multiple elements of their ].<ref name="Badoud_2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = Badoud D, Tsakiris M | title = From the body's viscera to the body's image: Is there a link between interoception and body image concerns? | journal = Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews | volume = 77 | pages = 237–246 | date = June 2017 | pmid = 28377099 | doi = 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.017 | s2cid = 768206 }}</ref> This exists in both people with anorexia and in healthy individuals due to impairment in interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness.<ref name="Badoud_2017" /> | |||

| Research into the ] of anorexia has indicated that many of the findings are inconsistent across studies and that it is hard to differentiate the effects of starvation on the brain from any long-standing characteristics. One finding is that those with anorexia have poor cognitive flexibility.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Tchanturia K, Campbell IC, Morris R, Treasure J |title=Neuropsychological studies in anorexia nervosa |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=37 Suppl |issue= |pages=S72–6; discussion S87–9 |year=2005 |pmid=15852325 |doi=10.1002/eat.20119}}</ref> | |||

| Aside from weight gain and outer appearance, people with anorexia also report abnormal bodily functions such as indistinct feelings of fullness.<ref name="Khalsa_2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = Khalsa SS, Lapidus RC | title = Can Interoception Improve the Pragmatic Search for Biomarkers in Psychiatry? | journal = Frontiers in Psychiatry | volume = 7 | pages = 121 | date = 2016 | pmid = 27504098 | pmc = 4958623 | doi = 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00121 | doi-access = free }}</ref> This provides an example of miscommunication between internal signals of the body and the brain. Due to impaired interoceptive sensitivity, powerful cues of fullness may be detected prematurely in highly sensitive individuals, which can result in decreased calorie consumption and generate anxiety surrounding food intake in anorexia patients.<ref name="Boswell_2015">{{Cite journal| vauthors = Boswell JF, Anderson LM, Anderson DA |date= June 2015|title=Integration of Interoceptive Exposure in Eating Disorder Treatment|journal=Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice|language=en|volume=22|issue=2|pages=194–210|doi=10.1111/cpsp.12103}}</ref> People with anorexia also report difficulty identifying and describing their emotional feelings and the inability to distinguish emotions from bodily sensations in general, called ].<ref name="Khalsa_2017" /> | |||

| Other studies have suggested that there are some ] and ] biases that may maintain anorexia.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cooper MJ |title=Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: progress, development and future directions |journal=Clinical Psychology Review |volume=25 |issue=4 |pages=511–31 |year=2005 |month=June |pmid=15914267 |doi=10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.003}}</ref> | |||

| Interoceptive awareness and emotion are deeply intertwined, and could mutually impact each other in abnormalities.<ref name="Boswell_2015" /> Anorexia patients also exhibit emotional regulation difficulties that ignite emotionally-cued eating behaviors, such as restricting food or excessive exercising.<ref name="Boswell_2015" /> Impaired interoceptive sensitivity and interoceptive awareness can lead anorexia patients to adapt distorted interpretations of weight gain that are cued by physical sensations related to digestion (e.g., fullness).<ref name="Boswell_2015" /> Combined, these interoceptive and emotional elements could together trigger maladaptive and negatively reinforced behavioral responses that assist in the maintenance of anorexia.<ref name="Boswell_2015" /> In addition to metacognition, people with anorexia also have difficulty with social cognition including interpreting others' emotions, and demonstrating empathy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kasperek-Zimowska BJ, Zimowski JG, Biernacka K, Kucharska-Pietura K, Rybakowski F | title = Impaired social cognition processes in Asperger syndrome and anorexia nervosa. In search for endophenotypes of social cognition | journal = Psychiatria Polska | volume = 50 | issue = 3 | pages = 533–542 | year = 2014 | pmid = 27556112 | doi = 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/33485 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Abnormal interoceptive awareness and interoceptive sensitivity shown through all of these examples have been observed so frequently in anorexia that they have become key characteristics of the illness.<ref name="Khalsa_2017" /> | |||

| ====Social and environmental==== | |||

| Sociocultural studies have highlighted the role of cultural factors, such as the promotion of thinness as the ] in Western industrialised nations, particularly through the media.{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} A recent epidemiological study of 989,871 Swedish residents indicated that ], ] and ] were large influences on the chance of developing anorexia, with those with non-European parents among the least likely to be diagnosed with the condition, and those in wealthy, white families being most at risk.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lindberg L, Hjern A |title=Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: a national cohort study |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=397–408 |year=2003 |month=December |pmid=14566927 |doi=10.1002/eat.10221}}</ref> People in professions where there is a particular social pressure to be thin (such as ] and ]s) were much more likely to develop anorexia during the course of their career,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Garner DM, Garfinkel PE |title=Socio-cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=647–56 |year=1980 |month=November |pmid=7208724 |doi=10.1017/S0033291700054945}}</ref> and further research has suggested that those with anorexia have much higher contact with cultural sources that promote weight-loss.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Toro J, Salamero M, Martinez E |title=Assessment of sociocultural influences on the aesthetic body shape model in anorexia nervosa |journal=Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica |volume=89 |issue=3 |pages=147–51 |year=1994 |month=March |pmid=8178671 |doi=10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb08084.x}}</ref> | |||

| === Comorbidity === | |||

| There is a high rate of reported child sexual abuse experiences in clinical groups of who have been diagnosed with anorexia. Although prior sexual abuse is not thought to be a specific risk factor for anorexia, those who have experienced such abuse are more likely to have more serious and chronic symptoms.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Carter JC, Bewell C, Blackmore E, Woodside DB |title=The impact of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa |journal=Child Abuse & Neglect |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=257–69 |year=2006 |month=March |pmid=16524628 |doi=10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.004}}</ref> | |||

| Other psychological issues may factor into anorexia nervosa. Some pre-existing disorders can increase a person's likelihood to develop an eating disorder. Additionally, Anorexia Nervosa can contribute to the development of certain conditions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Strober M, Freeman R, Lampert C, Diamond J | title = The association of anxiety disorders and obsessive compulsive personality disorder with anorexia nervosa: evidence from a family study with discussion of nosological and neurodevelopmental implications | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 40 | issue = S3 | pages = S46–S51 | date = November 2007 | pmid = 17610248 | doi = 10.1002/eat.20429 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The presence of psychiatric comorbidity has been shown to affect the severity and type of anorexia nervosa symptoms in both adolescents and adults.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Brand-Gothelf A, Leor S, Apter A, Fennig S | title = The impact of comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders on severity of anorexia nervosa in adolescent girls | language = en-US | journal = The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease | volume = 202 | issue = 10 | pages = 759–762 | date = October 2014 | pmid = 25265267 | doi = 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000194 | s2cid = 6023688 }}</ref> | |||

| ] remains highly prevalent among patients with anorexia nervosa, with more comorbid PTSD being associated with more severe eating disorder symptoms.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Rijkers |first=Cleo |title=Eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder |journal=Current Opinion in Psychiatry |date=2019 |volume=32 |issue=6 |pages=510–517|doi=10.1097/YCO.0000000000000545 |pmid=31313708 |url=https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/118591933/Eating_disorders_and_posttraumatic_stress_disorder.8.pdf }}</ref> ] (OCD) and ] (OCPD) are highly comorbid with AN.<ref name="Godier_2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Godier LR, Park RJ | title = Compulsivity in anorexia nervosa: a transdiagnostic concept | journal = Frontiers in Psychology | volume = 5 | pages = 778 | year = 2014 | pmid = 25101036 | pmc = 4101893 | doi = 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00778 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Halmi KA, Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Crow S, Fichter MM, Kaplan AS, Keel P, Klump KL, Lilenfeld LR, Mitchell JE, Plotnicov KH, Pollice C, Rotondo A, Strober M, Woodside DB, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH, Bulik CM | title = The relation among perfectionism, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder in individuals with eating disorders | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 38 | issue = 4 | pages = 371–374 | date = December 2005 | pmid = 16231356 | doi = 10.1002/eat.20190 | doi-access = free }}</ref> OCD is linked with more severe symptomatology and worse prognosis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Crane AM, Roberts ME, Treasure J | title = Are obsessive-compulsive personality traits associated with a poor outcome in anorexia nervosa? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and naturalistic outcome studies | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 40 | issue = 7 | pages = 581–588 | date = November 2007 | pmid = 17607713 | doi = 10.1002/eat.20419 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The ] between personality disorders and eating disorders has yet to be fully established.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gárriz M, Andrés-Perpiñá S, Plana MT, Flamarique I, Romero S, Julià L, Castro-Fornieles J | title = Personality disorder traits, obsessive ideation and perfectionism 20 years after adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: a recovered study | journal = Eating and Weight Disorders | volume = 26 | issue = 2 | pages = 667–677 | date = March 2021 | pmid = 32350776 | doi = 10.1007/s40519-020-00906-7 | quote = However, prospective studies are still scarce and the results from current literature regarding causal connections between AN and personality are unavailable. | s2cid = 216649851 }}</ref> Other comorbid conditions include ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Casper RC | title = Depression and eating disorders | journal = Depression and Anxiety | volume = 8 | issue = Suppl 1 | pages = 96–104 | year = 1998 | pmid = 9809221 | doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)8:1+<96::AID-DA15>3.0.CO;2-4 | s2cid = 36772859 | doi-access = free }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite book|title=Handbook of Alcoholism |page=|publisher=CRC Press|date=24 March 2000|isbn=978-1-4200-3696-1|vauthors=Zernig G, Saria A, Kurz M, O'Malley S}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Devoe |first1=Daniel J. |last2=Dimitropoulos |first2=Gina |last3=Anderson |first3=Alida |last4=Bahji |first4=Anees |last5=Flanagan |first5=Jordyn |last6=Soumbasis |first6=Andrea |last7=Patten |first7=Scott B. |last8=Lange |first8=Tom |last9=Paslakis |first9=Georgios |date=2021-12-11 |title=The prevalence of substance use disorders and substance use in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=161 |doi=10.1186/s40337-021-00516-3 |doi-access=free |issn=2050-2974 |pmc=8666057 |pmid=34895358}}</ref> ] and other ]s,<ref>{{Cite book|title=Personality Disorders and Eating Disorders: Exploring the Frontier |page=|publisher=Routledge|date=21 August 2013|isbn=978-1-135-44280-4|vauthors=Sansone RA, Levitt JL}}</ref><ref name="Halmi_2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Halmi KA | title = Perplexities of treatment resistance in eating disorders | journal = BMC Psychiatry | volume = 13 | pages = 292 | date = November 2013 | pmid = 24199597 | pmc = 3829659 | doi = 10.1186/1471-244X-13-292 | doi-access = free }}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Swinbourne JM, Touyz SW | title = The co-morbidity of eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review | journal = European Eating Disorders Review | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 253–274 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17676696 | doi = 10.1002/erv.784 | doi-access = free }}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cortese S, Bernardina BD, Mouren MC | title = Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and binge eating | journal = Nutrition Reviews | volume = 65 | issue = 9 | pages = 404–411 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17958207 | doi = 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00318.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> and ] (BDD).<ref>{{Cite book|title=Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual |page= |publisher=Guilford Press|date=18 December 2012|isbn=978-1-4625-0790-0|vauthors=Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G}}</ref> Depression and anxiety are the most common comorbidities,<ref name="Berkman_2006">{{cite journal | vauthors = Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, Lohr KN, Sedway JA, Rooks A, Gartlehner G | title = Management of eating disorders | journal = Evidence Report/Technology Assessment | issue = 135 | pages = 1–166 | date = April 2006 | pmid = 17628126 | pmc = 4780981 | url = http://archive.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/eatingdisorders/eatdis.pdf | url-status = live | df = dmy-all | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141222114708/http://archive.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/eatingdisorders/eatdis.pdf | archive-date = 22 December 2014 }}</ref> and depression is associated with a worse outcome.<ref name="Berkman_2006" /> | |||

| ====Relationship to autism==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Following an initial suggestion of relationship between anorexia nervosa and ],<ref name=Gillberg1985>{{cite journal |doi=10.3109/08039488509101911 |title=Autism and anorexia nervosa: Related conditions? |year=1985 |last1=Gillberg |first1=Christopher |journal=Nordic Journal of Psychiatry |volume=39 |pages=307}}</ref><ref name ="Rothery">{{cite journal |author=Rothery DJ, Garden GM |title=Anorexia nervosa and infantile autism |journal=The British Journal of Psychiatry |volume=153 |issue= |pages=714 |year=1988 |month=November |pmid=3255470 |doi=10.1192/bjp.153.5.714}}</ref><ref name=Gillberg1>{{cite journal |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=27–32 |last1=Gillberg |first1=C. |last2=Rastam |first2=M. |title=Do some cases of anorexia nervosa reflect underlying autistic-like conditions? | |||

| |journal=Behavioural neurology |year=1992}}</ref> a ] of 102 participants into teenage onset anorexia nervosa conducted in Sweden found that 23% of people with a long-standing eating disorder are on the ].<ref name=Gillberg2>{{cite journal |author=Gillberg IC, Råstam M, Gillberg C |title=Anorexia nervosa 6 years after onset: Part I. Personality disorders |journal=Comprehensive Psychiatry |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=61–9 |year=1995 |pmid=7705090 |doi=10.1016/0010-440X(95)90100-A}}</ref><ref name=Gillberg3>{{cite journal |author=Gillberg IC, Gillberg C, Råstam M, Johansson M |title=The cognitive profile of anorexia nervosa: a comparative study including a community-based sample |journal=Comprehensive Psychiatry |volume=37 |issue=1 |pages=23–30 |year=1996 |pmid=8770522 |doi=10.1016/S0010-440X(96)90046-2}}</ref><ref name="Råstam1">{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/BF01537541 |title=A six-year follow-up study of anorexia nervosa subjects with teenage onset |year=1996 |last1=Råstam |first1=M. |last2=Gillberg |first2=C. |last3=Gillberg |first3=I. C. |journal=Journal of Youth and Adolescence |volume=25 |pages=439}}</ref><ref name=Nilsson1>{{cite journal |author=Nilsson EW, Gillberg C, Gillberg IC, Råstam M |title=Ten-year follow-up of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: personality disorders |journal=Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry |volume=38 |issue=11 |pages=1389–95 |year=1999 |month=November |pmid=10560225 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0890-8567&volume=38&issue=11&spage=1389}}</ref><ref name=Wentz1>{{cite journal |author=Wentz E, Gillberg C, Gillberg IC, Råstam M |title=Ten-year follow-up of adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: psychiatric disorders and overall functioning scales |journal=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines |volume=42 |issue=5 |pages=613–22 |year=2001 |month=July |pmid=11464966 |doi=10.1017/S0021963001007284}}</ref><ref name=Råstam2>{{cite journal |author=Råstam M, Gillberg C, Wentz E |title=Outcome of teenage-onset anorexia nervosa in a Swedish community-based sample |journal=European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry |volume=12 |issue=Suppl 1 |pages=I78–90 |year=2003 |pmid=12567219 |doi=10.1007/s00787-003-1111-y}}</ref><ref name=Wentz2>{{cite journal |author=Wentz E, Lacey JH, Waller G, Råstam M, Turk J, Gillberg C |title=Childhood onset neuropsychiatric disorders in adult eating disorder patients. A pilot study |journal=European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry |volume=14 |issue=8 |pages=431–7 |year=2005 |month=December |pmid=16341499 |doi=10.1007/s00787-005-0494-3}}</ref> Those on autism spectrum tend to have a worse outcome,<ref name="Wentz3">{{cite journal |author=Wentz E, Gillberg IC, Anckarsäter H, Gillberg C, Råstam M |title=Adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: 18-year outcome |journal=The British Journal of Psychiatry |volume=194 |issue=2 |pages=168–74 |year=2009 |month=February |pmid=19182181 |doi=10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048686}}</ref> but may benefit from the combined use of behavioural and pharmacological therapies tailored to ameliorate autism rather than anorexia nervosa ].<ref name="Fisman">{{cite journal |author=Fisman S, Steele M, Short J, Byrne T, Lavallee C |title=Case study: anorexia nervosa and autistic disorder in an adolescent girl |journal=Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry |volume=35 |issue=7 |pages=937–40 |year=1996 |month=July |pmid=8768355 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0890-8567&volume=35&issue=7&spage=937}}</ref><ref name="Kerbeshian">{{cite journal |doi=10.1080/15622970802043117 |title=Is anorexia nervosa a neuropsychiatric developmental disorder? An illustrative case report |year=2009 |last1=Kerbeshian |first1=Jacob |last2=Burd |first2=Larry |journal=World Journal of Biological Psychiatry |volume=10 |pages=648}}</ref> Other studies may suggest that autistic traits are common in people with anorexia nervosa.<ref name=Gillberg4>{{cite journal |author=Gillberg IC, Råstam M, Wentz E, Gillberg C |title=Cognitive and executive functions in anorexia nervosa ten years after onset of eating disorder |journal=Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology |volume=29 |issue=2 |pages=170–8 |year=2007 |month=February |pmid=17365252 |doi=10.1080/13803390600584632}}</ref><ref name=Lopez1>{{cite journal |author=Lopez C, Tchanturia K, Stahl D, Booth R, Holliday J, Treasure J |title=An examination of the concept of central coherence in women with anorexia nervosa |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=41 |issue=2 |pages=143–52 |year=2008 |month=March |pmid=17937420 |doi=10.1002/eat.20478}}</ref><ref name="Russell1">{{cite journal |author=Russell TA, Schmidt U, Doherty L, Young V, Tchanturia K |title=Aspects of social cognition in anorexia nervosa: affective and cognitive theory of mind |journal=Psychiatry Research |volume=168 |issue=3 |pages=181–5 |year=2009 |month=August |pmid=19467562 |doi=10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.028}}</ref><ref name=Zastrow>{{cite journal |author=Zastrow A, Kaiser S, Stippich C, ''et al.'' |title=Neural correlates of impaired cognitive-behavioral flexibility in anorexia nervosa |journal=The American Journal of Psychiatry |volume=166 |issue=5 |pages=608–16 |year=2009 |month=May |pmid=19223435 |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050775}}</ref><ref name="Harrison">{{cite journal |author=Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J |title=Emotion recognition and regulation in anorexia nervosa |journal=Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=348–56 |year=2009 |pmid=19517577 |doi=10.1002/cpp.628}}</ref> However, in one report it was concluded that these findings need to be replicated using larger samples with more sensitive measures.<ref name=Hambrook1>{{cite journal |author=Hambrook D, Tchanturia K, Schmidt U, Russell T, Treasure J |title=Empathy, systemizing, and autistic traits in anorexia nervosa: a pilot study |journal=The British Journal of Clinical Psychology |volume=47 |issue=Pt 3 |pages=335–9 |year=2008 |month=September |pmid=18208640 |doi=10.1348/014466507X272475}}</ref> | |||

| ] disorders occur more commonly among people with eating disorders than in the general population,<ref name="Huke_2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Huke V, Turk J, Saeidi S, Kent A, Morgan JF | title = Autism spectrum disorders in eating disorder populations: a systematic review | journal = European Eating Disorders Review | volume = 21 | issue = 5 | pages = 345–351 | date = September 2013 | pmid = 23900859 | doi = 10.1002/erv.2244 }}</ref> with about 30% of children and adults with AN likely having autism.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Inal-Kaleli |first1=Ipek |last2=Dogan |first2=Nurhak |last3=Kose |first3=Sezen |last4=Bora |first4=Emre |date=2024-11-12 |title=Investigating the Presence of Autistic Traits and Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |doi=10.1002/eat.24307 |issn=1098-108X |pmid=39530423|doi-access=free }}</ref> Zucker ''et al.'' (2007) proposed that conditions on the autism spectrum make up the ] underlying anorexia nervosa and appealed for increased interdisciplinary collaboration.<ref name="Zucker_2007">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zucker NL, Losh M, Bulik CM, LaBar KS, Piven J, Pelphrey KA | title = Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes | journal = Psychological Bulletin | volume = 133 | issue = 6 | pages = 976–1006 | date = November 2007 | pmid = 17967091 | doi = 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976 | url = http://www.duke.edu/web/mind/level2/faculty/labar/pdfs/Zucker_et_al_2007.pdf | url-status = live | df = dmy-all | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100420183125/http://www.duke.edu/web/mind/level2/faculty/labar/pdfs/Zucker_et_al_2007.pdf | archive-date = 20 April 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| It is also proposed that conditions on the autism spectrum make up the ] underlying anorexia nervosa and appealed for increased interdisciplinary collaboration (see figure to right).<ref name="Zucker1">{{cite journal |author=Zucker NL, Losh M, Bulik CM, LaBar KS, Piven J, Pelphrey KA |title=Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders: guided investigation of social cognitive endophenotypes |journal=Psychological Bulletin |volume=133 |issue=6 |pages=976–1006 |year=2007 |month=November |pmid=17967091 |doi=10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.976}}</ref> A pilot study into the effectiveness ], which based its treatment protocol on the hypothesised relationship between anorexia nervosa and an underlying autistic like condition, reduced perfectionism and rigidity in 17 out of 19 participants<ref name="Whitney">{{cite journal |author=Whitney J, Easter A, Tchanturia K |title=Service users' feedback on cognitive training in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=41 |issue=6 |pages=542–50 |year=2008 |month=September |pmid=18433016 |doi=10.1002/eat.20536}}</ref> although further evaluation is needed. | |||

| == |

== Causes == | ||

| ] pathways has been implicated in the cause and mechanism of anorexia.<ref name="Rikani_2013">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rikani AA, Choudhry Z, Choudhry AM, Ikram H, Asghar MW, Kajal D, Waheed A, Mobassarah NJ |date=October 2013 |title=A critique of the literature on etiology of eating disorders |journal=Annals of Neurosciences |volume=20 |issue=4 |pages=157–161 |doi=10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200409 |pmc=4117136 |pmid=25206042}}</ref>]] | |||

| Anorexia is thought to have the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, with anywhere from 6-20% of those who are diagnosed with the disorder eventually dying from related causes.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Herzog DB, Greenwood DN, Dorer DJ, ''et al.'' |title=Mortality in eating disorders: a descriptive study |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=20–6 |year=2000 |month=July |pmid=10800010 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200007)28:1<20::AID-EAT3>3.0.CO;2-X}}</ref> The suicide rate of people with anorexia is also higher than that of the general population.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Pompili M, Mancinelli I, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R |title=Suicide in anorexia nervosa: a meta-analysis |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=99–103 |year=2004 |month=July |pmid=15185278 |doi=10.1002/eat.20011}}</ref> In a longitudinal study women diagnosed with either DSM-IV anorexia nervosa (n = 136) or bulimia nervosa (n = 110) respectively who were assessed every 6 – 12 months over an 8 year period are at a considerable risk of committing suicide. Clinicians were warned of the risks as 15% of subjects reported at least one suicide attempt. It was noted that significantly more anorexia (22.1%) than bulimia (10.9%) subjects made a suicide attempt.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Franko DL, Keel PK, Dorer DJ, ''et al.'' |title=What predicts suicide attempts in women with eating disorders? |journal=Psychological Medicine |volume=34 |issue=5 |pages=843–53 |year=2004 |month=July |pmid=15500305 |doi=10.1017/S0033291703001545}}</ref> | |||

| There is evidence for biological, psychological, developmental, and sociocultural risk factors, but the exact cause of eating disorders is unknown.<ref name="Rikani_2013" /> | |||

| ==Treatment== | |||

| Treatment for anorexia nervosa tries to address three main areas. 1) Restoring the person to a healthy weight; 2) Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness; 3) Reducing or eliminating behaviours or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.<ref>{{cite journal | author = National Institute of Mental Health | url = http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa.shtml}}</ref> | |||

| ===Genetic=== | |||

| Drug treatments, such as ] or other ] medication, have not been found to be generally effective for either treating anorexia,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Claudino AM, Hay P, Lima MS, Bacaltchuk J, Schmidt U, Treasure J |title=Antidepressants for anorexia nervosa |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD004365 |year=2006 |pmid=16437485 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD004365.pub2}}</ref> or preventing relapse<ref>{{cite journal |author=Walsh BT, Kaplan AS, Attia E, ''et al.'' |title=Fluoxetine after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial |journal=JAMA |volume=295 |issue=22 |pages=2605–12 |year=2006 |month=June |pmid=16772623 |doi=10.1001/jama.295.22.2605}}</ref> although it has also been noted that there is a lack of adequate research in this area. | |||

| ] | |||

| Anorexia nervosa is highly ].<ref name="Rikani_2013" /> Twin studies have shown a heritability rate of 28–58%.<ref name="Thornton_2011">{{cite book |vauthors=Thornton LM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM |chapter=The heritability of eating disorders: methods and current findings |title=Behavioral Neurobiology of Eating Disorders|volume=6 |pages=141–56 |year=2011 |pmid=21243474 |pmc=3599773 |doi=10.1007/7854_2010_91 |series=Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences |isbn=978-3-642-15130-9}}</ref> First-degree relatives of those with anorexia have roughly 12 times the risk of developing anorexia.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors=Hildebrandt T, Downey A |veditors=Charney D, Sklar P, Buxbaum J, Nestler E |title=Neurobiology of Mental Illness|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-993495-9 |edition=4th |chapter=The Neurobiology of Eating Disorders|date=4 July 2013}}</ref> ] have been performed, studying 128 different ] related to 43 ] including genes involved in regulation of eating behavior, ] and ], ] and ]. Consistent associations have been identified for polymorphisms associated with ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name="Rask-Andersen_2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rask-Andersen M, Olszewski PK, Levine AS, Schiöth HB | title = Molecular mechanisms underlying anorexia nervosa: focus on human gene association studies and systems controlling food intake | journal = Brain Research Reviews | volume = 62 | issue = 2 | pages = 147–164 | date = March 2010 | pmid = 19931559 | doi = 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.10.007 | s2cid = 37635456 }}</ref> ], such as ], may contribute to the development or maintenance of anorexia nervosa, though clinical research in this area is in its infancy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pjetri E, Schmidt U, Kas MJ, Campbell IC | title = Epigenetics and eating disorders | journal = Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 330–335 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22617563 | doi = 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283546fd3 | s2cid = 27183934 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hübel C, Marzi SJ, Breen G, Bulik CM | title = Epigenetics in eating disorders: a systematic review | journal = Molecular Psychiatry | volume = 24 | issue = 6 | pages = 901–915 | date = June 2019 | pmid = 30353170 | pmc = 6544542 | doi = 10.1038/s41380-018-0254-7 }}</ref> | |||

| A 2019 study found a genetic relationship with mental disorders, such as ], ], ] and ]; and metabolic functioning with a negative correlation with fat mass, ] and ].<ref name="Watson_2019">{{cite journal | vauthors = Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, Hübel C, Coleman JR, Gaspar HA, etal | title = Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa | journal = Nature Genetics | volume = 51 | issue = 8 | pages = 1207–1214 | date = August 2019 | pmid = 31308545 | pmc = 6779477 | doi = 10.1038/s41588-019-0439-2 }}</ref> | |||

| ] has also been found to be an effective treatment for adolescents with short term anorexia.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Lock J, le Grange D |title=Family-based treatment of eating disorders |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=37 Suppl |issue= |pages=S64–7; discussion S87–9 |year=2005 |pmid=15852323 |doi=10.1002/eat.20122}}</ref> At 4 to 5 year follow up one study shows full recovery rate of 60 - 90% with 10-15% remaining seriously ill. This compares favourable to other treatments such as inpatient care where full recovery rates vary between 33-55%.<ref>{{cite journal |author=le Grange D, Eisler I |title=Family interventions in adolescent anorexia nervosa |journal=Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=159–73 |year=2009 |month=January |pmid=19014864 |doi=10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.004}}</ref> | |||

| == |

===Environmental=== | ||

| ] complications: prenatal and perinatal complications may factor into the development of anorexia nervosa, such as ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Larsen JT, Bulik CM, Thornton LM, Koch SV, Petersen L | title = Prenatal and perinatal factors and risk of eating disorders | journal = Psychological Medicine | volume = 51 | issue = 5 | pages = 870–880 | date = April 2021 | pmid = 31910913 | doi = 10.1017/S0033291719003945 | s2cid = 210086516 | url = https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/downloads/8g84mw99r }}</ref> maternal ], ], ], ], and neonatal heart abnormalities.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jones C, Pearce B, Barrera I, Mummert A | title = Fetal programming and eating disorder risk | journal = Journal of Theoretical Biology | volume = 428 | pages = 26–33 | date = September 2017 | pmid = 28571669 | doi = 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.05.028 | bibcode = 2017JThBi.428...26J }}</ref> Neonatal complications may also have an influence on ], one of the ] associated with the development of AN.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Favaro A, Tenconi E, Santonastaso P | title = Perinatal factors and the risk of developing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa | journal = Archives of General Psychiatry | volume = 63 | issue = 1 | pages = 82–88 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16389201 | doi = 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.82 | s2cid = 45181444 }}</ref> | |||

| Neuroendocrine dysregulation: altered signaling of peptides that facilitate communication between the gut, brain and ], such as ], ], ] and ], may contribute to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa by disrupting regulation of hunger and satiety.<ref name="Davis_2011">{{cite book | chapter = 24. Orexigenic Hypothalamic Peptides Behavior and Feeding – 24.5 Orexin | pages = |vauthors=Davis JF, Choi DL, Benoit SC | title = Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition |veditors=Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin CR | publisher = Springer | year = 2011 | isbn = 978-0-387-92271-3 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Smitka K, Papezova H, Vondra K, Hill M, Hainer V, Nedvidkova J | title = The role of "mixed" orexigenic and anorexigenic signals and autoantibodies reacting with appetite-regulating neuropeptides and peptides of the adipose tissue-gut-brain axis: relevance to food intake and nutritional status in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa | journal = International Journal of Endocrinology | volume = 2013 | pages = 483145 | year = 2013 | pmid = 24106499 | pmc = 3782835 | doi = 10.1155/2013/483145 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| Anorexia has an incidence of between 8 and 13 cases per 100,000 persons per year and an average prevalence of 0.3% using strict criteria for diagnosis.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Bulik CM, Reba L, Siega-Riz AM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T |title=Anorexia nervosa: definition, epidemiology, and cycle of risk |journal=The International Journal of Eating Disorders |volume=37 |issue=S1 |pages=S2–9; discussion S20–1 |year=2005 |pmid=15852310 |doi=10.1002/eat.20107}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Hoek HW |title=Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders |journal=Current Opinion in Psychiatry |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=389–94 |year=2006 |month=July |pmid=16721169 |doi=10.1097/01.yco.0000228759.95237.78}}</ref> The condition largely affects young adolescent women, with between 15 and 19 years old making up 40% of all cases. Furthermore, the majority of cases are unlikely to be in contact with mental health services.{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} Approximately 90% of people with anorexia are female.<ref name="GowersBryant-Waugh2004">{{cite journal |author=Gowers S, Bryant-Waugh R |title=Management of child and adolescent eating disorders: the current evidence base and future directions |journal=Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines |volume=45 |issue=1 |pages=63–83 |year=2004 |month=January |pmid=14959803 |doi=10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00309.x}}</ref> | |||