| Revision as of 01:51, 15 February 2008 view sourceMani1 (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers8,827 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:51, 4 January 2025 view source UtherSRG (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators180,283 editsm Reverted edit by BobKilcoyne (talk) to last version by Great BrightstarTag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Family of mammals}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-vandalism}} | |||

| {{About|the ruminant animal}} | |||

| {{pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| {{redirect-multi|2|Fawn|Stag}} | |||

| {{otheruses1|the ruminant animal}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{redirect4|Fawn|Stag}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2017}} | |||

| | name = Deer | |||

| {{Automatic taxobox | |||

| | fossil_range = Early ] - Recent | |||

| | name = Deer<ref> among examples (swine OE swin, deer OE deor, sheep OE sceap, horse OE hors, year OE gear, pound OE pana) -Jespersen, A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles, Part II SYNTAX (First Volume), Ch.III The Unchanged Plural (p. 49) ''arrow.latrobe.edu.au'' accessed 14 November 2020</ref> | |||

| | image = Deer Valley Forge.JPG | |||

| | fossil_range = {{Fossil range|Early Miocene|Recent}} | |||

| | image_width = 250px | |||

| | image = Family Cervidae five species.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = A white-tail deer | |||

| | image_upright = 1.2 | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| | image_caption = Images of a few members of the family Cervidae (clockwise from top left): the ] (''Cervus elaphus''), ] (''Cervus nippon''), ] (''Rucervus duvaucelii''), ] (''Rangifer tarandus'') and ] (''Odocoileus virginianus'') | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | |

| taxon = Cervidae | ||

| | authority = ], 1820 | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | |

| type_genus = '']'' | ||

| | type_genus_authority = ], 1758 | |||

| | familia = '''Cervidae''' | |||

| | range_map = | |||

| | familia_authority = ], 1820 | |||

| | range_map_caption = Combined native range of all species of deer. | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Subfamilies | | subdivision_ranks = Subfamilies | ||

| | subdivision = | | subdivision = *] | ||

| *] | |||

| ]/Odocoileinae<br> | |||

| ]<br> | |||

| ]<br> | |||

| ]<br> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| A '''deer''' is a ] ] belonging to the ] '''Cervidae'''. A number of broadly similar animals from related families within the ] ] (even-toed ]) are often also called ''deer''. Male deer grow and shed new antlers each year, as opposed to ], which are in the same order and bear a superficial resemblance to deer physically, but are permanently horned. | |||

| A '''deer''' ({{plural form}}: deer) or '''true deer''' is a hoofed ] ] of the ] '''Cervidae''' (informally the '''deer family'''). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies ] (which includes, among others, ], ] (wapiti), ], and ]) and ] (which includes, among others ] (caribou), ], ], and ]). Male deer of almost all species (except the ]), as well as female reindeer, grow and shed new ]s each year. These antlers are bony extensions of the skull and are often used for combat between males. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| <span id="doe"/> | |||

| Depending on their species, male deer are called ''stags, harts, bucks'' or ''bulls,'' and females are called ''hinds, does'' or ''cows.'' Young deer are called ''fawns'' or ''calves''. A group of deer is commonly called a ''herd''. ''Hart,'' from ] ''heorot'' ‘deer’, is a term for a stag, particularly a ] stag past its fifth year. It is not commonly used, but ] makes several references, punning the sound alike "hart" and "heart" for example in ]. "The White Hart" and "The Red Hart" are common English ] names, and the county ] is named after them. | |||

| The ] (]) of Asia and ]s (]) of tropical African and Asian forests are separate families that are also in the ruminant clade ]; they are not especially closely related to Cervidae. | |||

| The ] deer was originally quite broad in meaning and came to be ]. In ], ''der'' (] ''dēor'') meant a beast or ] of any kind. This general sense gave way to the modern sense by the end of the Middle English period, around 1500. The ] word ''Tier'', the ] word ''dier'' and the ] words ''djur/dyr/dýr'', cognates of English deer, still have the general sense of "animal." | |||

| The ] pertaining to deer is '']''. | |||

| Deer appear in art from ] cave paintings onwards, and they have ], religion, and literature throughout history, as well as in ], such as red deer that appear in the ].<ref>Iltanen, Jussi: ''Suomen kuntavaakunat'' (2013), Karttakeskus, {{ISBN|951-593-915-1}}</ref> Their economic importance includes the use of their meat as ], their skins as soft, strong ], and their antlers as handles for knives. ] has been a popular activity since the Middle Ages and remains a resource for many families today. | |||

| == Habitat == | |||

| ==Etymology and terminology== | |||

| Deer are widely distributed, and ], with indigenous representatives in all continents except ] and ], though ] has only one native species confined to the ] in the north-west of the continent, the ]. (The ] of African forests is not a true deer; all other animals in Africa resembling deer are antelope). | |||

| ]" by ], 1529]] | |||

| Deer live in a variety of biomes ranging from ] to the ]. While often associated with forests, many deer are ] species that live in transitional areas between forests and thickets (for cover) and prairie and savanna (open space). The majority of large deer species inhabit temperate mixed deciduous forest, mountain mixed coniferous forest, tropical seasonal/dry forest, and savanna habitats around the world. Clearing open areas within forests to some extent may actually benefit deer populations by exposing the understory and allowing the types of grasses, weeds, and herbs to grow that deer like to eat. However, adequate forest or brush cover must still be provided for populations to grow and thrive. | |||

| The word ''deer'' was originally broad in meaning, becoming more specific with time. ] {{lang|ang|dēor}} and ] {{lang|enm|der}} meant a wild animal of any kind. <!--In Shakespeare's time, "small deer" meant any type of petty game, not worth pursuing,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Small+deer |title=Small deer |access-date=12 April 2016}}</ref> in contrast to '']'', which then meant any sort of domestic livestock that could be removed from the land, related to personal-property ownership, as with modern '']'' (property) and ]. Wild animals in a forest were considered part of ], and sold with the land.--> Cognates of Old English {{lang|ang|dēor}} in other dead ] have the general sense of ''animal'', such as ] ''tior'', ] {{lang|non|djur}} or {{lang|non|dȳr}}, ] ''dius'', ] ''dier'', and ] ''diar''.<ref name="Ref_">{{cite book |chapter-url=http://www.bartleby.com/61/75/D0087500.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040325232020/http://www.bartleby.com/61/75/D0087500.html |archive-date=25 March 2004 |chapter=deer|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company |title=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language |edition=4th |year=2000}}</ref> This general sense gave way to the modern English sense by the end of the Middle English period, around 1500. All modern Germanic languages save English and Scots retain the more general sense: for example, ]/] {{lang|nl|dier}}, ] {{lang|de|Tier}}, and ] ''dyr'' mean {{gloss|animal}}.<ref>{{cite web |last=Harper |first=Douglas |website=Online Etymology Dictionary |title=Deer |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=deer |access-date=7 June 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ] deer]] | |||

| Small species such as the ] and ]s of Central and South America, and the ]s of Asia occupy dense forests and are less often seen in open spaces. There are also several species of deer that are highly specialized, and live almost exclusively in mountains, grasslands, swamps and "wet" savannas, or riparian corridors surrounded by deserts. Some deer have a circumpolar distribution in both North America and Eurasia. Examples include the ] that live in Arctic tundra and taiga (boreal forests) and ] that inhabit ] and adjacent areas. | |||

| For many types of deer in modern English usage, the male is a ''buck'' and the female a ''doe'', but the terms vary with dialect, and according to the size of the species. The male ] is a ''stag'', while for other large species the male is a ''bull'', the female a ''cow'', as in cattle. In older usage, the male of any species is a '']'', especially if over five years old, and the female is a ''hind'', especially if three or more years old.<ref>], s.v. ''hart'' and ''hind''</ref> The young of small species is a ''fawn'' and of large species a '']''; a very small young may be a ''kid''. A castrated male is a ''havier''.<ref>{{cite dictionary|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/havier?s=t |title=Havier|dictionary=Dictionary.com |access-date=4 August 2012}}</ref> A group of any species is a ''herd''. The ] of relation is '']''; like the family name ''Cervidae'', this is from {{langx|la|cervus}}, meaning {{gloss|stag}} or {{gloss|deer}}. | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate ] lies in the Canadian Rocky Mountain and Columbia Mountain Regions between Alberta and British Columbia where all five North American deer species (], ], ], ], and ]) can be found. This is a region that boasts mountain slopes with diverse types of coniferous and mixed forested areas along with lush alpine meadows. The foothills and river valleys between the mountain ranges provide a mosaic of cropland and deciduous parklands. The aspen parklands north of Calgary also have many lakes and marshes. Elk and Mule Deer are probably the most common animals throughout the region. The caribou live at higher altitudes in the subalpine meadows and alpine tundra areas. The White-tailed Deer have recently expanded their range within the foothills and river valleys of the Canadian Rockies due to conversion of land to cropland and the clearing of coniferous forests allowing more deciduous vegetation to grow. They often share this riparian habitat with moose, but left the adjacent ] and drier grassland habitats to ], ], and ] antelope. | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate Asia occurs in the mixed deciduous forests, mountain coniferous forests, and taiga bordering North Korea, Manchuria (Northeastern China), and the Ussuri Region (Russia). These are among some of the richest deciduous and coniferous forests in the world where one can find ], ], ], ], and ]. Just south of this region in China, one can find the unusual ]. Deer such as the ], ], ], and ] have historically been farmed for their antlers by ], ], ], ], and ]. Like the ] of ] and ], the ], ], and ] of Southern Siberia, Northern Mongolia, and the Ussuri Region have also taken to raising semi-domesticated herds of ]. | |||

| ==Distribution== | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in the tropics occurs in Southern Asia and Southeast Asia in the Countries of India, Nepal, and at one time, Thailand. Northern India's Indo-Gangetic Plain Region and Nepal's Terai Region consist of tropical seasonal moist deciduous, dry deciduous forests, and both dry and wet savannas that are home to ], ], ], Indian ], and ]. Just slightly north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain is the Vale of Kashmir, home to the rare Kashmir Stag, a subspecies of ]. The Chao Praya River Valley of Thailand was once primarily tropical seasonal moist deciduous forest and wet savanna that hosted populations of ], ] (now extinct), ], Indian ], and ]. Today, both the ] and ] are endangered or rare. The hog deer populations in Thailand are also rare. Chital and Barasingha live in large herds, and Indian sambar may also be found in large groups. Of all these deer species, hog deer are solitary and have the lowest deer densities. How all these deer can co-exist in one area is due to the fact that they prefer different types of vegetation for food. These deer also share their habitat with various herbivores such as Asian elephants, various antelope species (i,e, ... such as ], ], ], and Indian ] in India), and wild oxen (i.e., ... such as ], ], and ]). Incidentally, the European deciduous forests and North American deciduous forests (west of the Appalachian Mountains) were historically also shared by both deer species and wild oxen. The mixed deciduous forests and prairies of Europe were once home to European Red Deer, European Roe Deer, Moose, ] (forest ox), and ] (European bison). The mixed deciduous forests and prairies of North America's midwest were once home to ] and large herds of ] and ]. Today most of these forest and prairie lands have become converted to cropland. Much of the forest and prairie land west of North America's Appalachian Mountains is part of United States' Midwest Agricultural Region and primarily supports white-tailed deer. The ] and ] herds have recently (the past century) become extinct in these areas with elk and bison reintroduced to some areas. The forests of Europe are also mostly cropland and European Red Deer and European Roe Deer survive only in protected areas. The ] are an extinct, but are believed to be the ancestors of today's domestic cattle. The ] almost became extinct, but have survived in captivity and have been reintroduced to some forest reserves in Europe. | |||

| {{anchor|doe}} | |||

| Australia has six ] of deer that have established sustainable wild populations from Acclimatisation Society releases in the 19th Century. These are ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ] deer in ], India]] | |||

| Red Deer introduced into ] in 1851 from English and Scottish stock were domesticated in ]s by the late 1960s and are common farm animals there now. Seven other species of deer were introduced into New Zealand but none are as widespread as Red Deer.<ref name="DeerInNewZealand"> An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand 1966</ref> | |||

| Deer live in a variety of ]s, ranging from ] to the ]. While often associated with forests, many deer are ] species that live in transitional areas between forests and thickets (for cover) and prairie and savanna (open space). The majority of large deer species inhabit temperate mixed deciduous forest, mountain mixed coniferous forest, tropical seasonal/dry forest, and savanna habitats around the world. Clearing open areas within forests to some extent may actually benefit deer populations by exposing the ] and allowing the types of grasses, weeds, and herbs to grow that deer like to eat. Access to adjacent croplands may also benefit deer. Adequate forest or brush cover must still be provided for populations to grow and thrive. | |||

| Deer are widely distributed, with indigenous representatives in all continents except ] and ], though ] has only one native deer, the ], a subspecies of ] that is confined to the ] in the northwest of the continent. Another extinct species of deer, ''],'' was present in ] until 6000 years ago. ] have been introduced to ]. Small species of ] and ]s of ] and ], and ]s of ] generally occupy dense forests and are less often seen in open spaces, with the possible exception of the ]. There are also several species of deer that are highly specialized and live almost exclusively in mountains, grasslands, swamps, and "wet" savannas, or ] surrounded by ]s. Some deer have a circumpolar distribution in both ] and ]. Examples include the ] that live in Arctic ] and ] (boreal forests) and ] that inhabit taiga and adjacent areas. Huemul deer (] and ]) of ]'s ] fill the ecological niches of the ] and ], with the fawns behaving more like ] kids. | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate North America lies in the ] and ] regions between Alberta and British Columbia where all five North American deer species (], ], ], ], and ]) can be found. This region has several clusters of national parks including ], ], ], and ] on the British Columbia side, and ], ], and ] on the Alberta and Montana sides. Mountain slope habitats vary from moist coniferous/mixed forested habitats to dry subalpine/pine forests with alpine meadows higher up. The foothills and river valleys between the mountain ranges provide a mosaic of cropland and deciduous parklands. The rare woodland caribou have the most restricted range living at higher altitudes in the subalpine meadows and ] areas of some of the mountain ranges. Elk and mule deer both migrate between the alpine meadows and lower coniferous forests and tend to be most common in this region. Elk also inhabit river valley bottomlands, which they share with White-tailed deer. The White-tailed deer have recently expanded their range within the foothills and river valley bottoms of the Canadian Rockies owing to conversion of land to cropland and the clearing of coniferous forests allowing more deciduous vegetation to grow up the mountain slopes. They also live in the aspen parklands north of Calgary and Edmonton, where they share habitat with the moose. The adjacent ] grassland habitats are left to herds of elk, ], and ]. | |||

| ] herds standing on snow to avoid flies]] | |||

| The ]n Continent (including the Indian Subcontinent) boasts the most species of deer in the world, with most species being found in Asia. Europe, in comparison, has lower diversity in plant and animal species. Many national parks and protected reserves in Europe have populations of red deer, ], and fallow deer. These species have long been associated with the continent of Europe, but also inhabit ], the ], and Northwestern ]. "European" fallow deer historically lived over much of Europe during the Ice Ages, but afterwards became restricted primarily to the Anatolian Peninsula, in present-day Turkey. | |||

| Present-day fallow deer populations in Europe are a result of historic man-made introductions of this species, first to the Mediterranean regions of Europe, then eventually to the rest of Europe. They were initially park animals that later escaped and reestablished themselves in the wild. Historically, Europe's deer species shared their deciduous forest habitat with other herbivores, such as the extinct ] (forest horse), extinct ] (forest ox), and the endangered ] (European bison). Good places to see deer in Europe include the ], the ]n ], the ] between ], ], and the ], and some National Parks, including ] in ], the ] in the ], the ] in ], and ] in ]. ], ], and the ] have forest areas that are not only home to sizable deer populations but also other animals that were once abundant such as the wisent, ], ], ], and ]s. | |||

| ] (''Cervus nippon'') and ] (''Macaca fuscata'') along a waterside]] | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in temperate Asia occurs in the mixed deciduous forests, mountain coniferous forests, and taiga bordering North Korea, Manchuria (Northeastern China), and the Ussuri Region (Russia). These are among some of the richest deciduous and coniferous forests in the world where one can find ], ], elk, and moose. Asian caribou occupy the northern fringes of this region along the Sino-Russian border. | |||

| Deer such as the sika deer, ], ], and elk have historically been farmed for their antlers by ], ], ], ]ns, and ]. Like the ] of Finland and Scandinavia, the Tungusic peoples, Mongolians, and Turkic peoples of Southern Siberia, Northern Mongolia, and the Ussuri Region have also taken to raising semi-domesticated herds of Asian caribou. | |||

| The highest concentration of large deer species in the tropics occurs in Southern Asia in India's Indo-Gangetic Plain Region and ]'s Terai Region. These fertile plains consist of tropical seasonal moist deciduous, dry deciduous forests, and both dry and wet savannas that are home to ], ], ], Indian ], and ]. Grazing species such as the endangered barasingha and very common chital are gregarious and live in large herds. Indian sambar can be gregarious but are usually solitary or live in smaller herds. Hog deer are solitary and have lower densities than Indian muntjac. Deer can be seen in several national parks in India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka of which ], ], and ] are most famous. Sri Lanka's ] and ] have large herds of Indian sambar and chital. The Indian sambar are more gregarious in Sri Lanka than other parts of their range and tend to form larger herds than elsewhere. | |||

| ] does and a ] buck roaming the ] in southern India]] | |||

| The Chao Praya River Valley of Thailand was once primarily tropical seasonal moist deciduous forest and wet savanna that hosted populations of hog deer, the now-extinct ], ], Indian sambar, and Indian muntjac. Both the hog deer and Eld's deer are rare, whereas Indian sambar and Indian muntjac thrive in protected national parks, such as ]. Many of these South Asian and Southeast Asian deer species also share their habitat with other ], such as ]s, the various Asian rhinoceros species, various antelope species (such as ], ], ], and ] in India), and wild oxen (such as ], ], ], and ]). One way that different herbivores can survive together in a given area is for each species to have different food preferences, although there may be some overlap. | |||

| As a result of ] releases in the 19th century, Australia has six ] of deer that have established sustainable wild populations. They are fallow deer, red deer, sambar, hog deer, ], and chital. Red deer were introduced into New Zealand in 1851 from English and Scottish stock. Many have been domesticated in ]s since the late 1960s and are common farm animals there now. Seven other species of deer were introduced into New Zealand but none are as widespread as red deer.<ref name="DeerInNewZealand">{{cite web|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/mammals-introduced/page-10|title=Deer|website=Te Ara: An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand|year=1966|editor-first=A. H.|editor-last=McLintock}}</ref> | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| ] | ] | ] | ] | ]}}]] | |||

| Deer constitute the second most diverse family of artiodactyla after bovids.<ref name=Groves2007/> Though of a similar build, deer are strongly distinguished from ]s by their ]s, which are temporary and regularly regrown unlike the permanent ]s of bovids.<ref name="Kingdon2015">{{cite book|last1=Kingdon|first1=J.|author1-link=Jonathan Kingdon|title=The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals|date=2015|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|location=London, UK|isbn=978-1-4729-2531-2|page=499|edition=2nd}}</ref> Characteristics typical of deer include long, powerful legs, a diminutive tail and long ears.<ref name="Jameson">{{cite book|last1=Jameson|first1=E. W.|last2=Peeters| first2=H. J. Jr. |title=Mammals of California|date=2004|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley, US|isbn=978-0-520-23582-3|page=241|edition=Revised}}</ref> Deer exhibit a broad variation in physical proportions. The ] extant deer is the ], which is nearly {{convert|2.6|m|ftin}} tall and weighs up to {{convert|800|kg|lb}}.<ref name="Long">{{cite book|last1=Long|first1=C. A.|title=The Wild Mammals of Wisconsin|url=https://archive.org/details/wildmammalswisco00long|url-access=limited|date=2008|publisher=Pensoft|location=Sofia, Bulgaria|isbn=9789546423139|page=}}</ref><ref name="Prothero2002">{{cite book|last1=Prothero|first1=D. R.|author1-link=Donald Prothero|last2=Schoch|first2=R. M.|title=Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals|date=2002|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore, US|isbn=978-0-8018-7135-1|pages=61–84}}</ref> The elk stands {{convert|1.4|–|2|m|ftin}} at the shoulder and weighs {{convert|240|–|450|kg|lb}}.<ref name="Kurta">{{cite book|last1=Kurta|first1=A.|title=Mammals of the Great Lakes Region|date=1995|publisher=University of Michigan Press|location=Michigan, US|isbn=978-0-472-06497-7|pages=|edition=1st|url=https://archive.org/details/mammalsofgreatla00kurt_0/page/260}}</ref> The northern pudu is the smallest deer in the world; it reaches merely {{convert|32|–|35|cm|in|frac=2}} at the shoulder and weighs {{convert|3.3|–|6|kg|lb|frac=4}}. The southern pudu is only slightly taller and heavier.<ref name=Geist/> ] is quite pronounced – in most species males tend to be larger than females,<ref name="Armstrong">{{cite book|last1=Armstrong|first1=D. M.|last2=Fitzgerald|first2=J. P.|last3=Meaney|first3=C. A.|title=Mammals of Colorado|date=2011|publisher=University Press of Colorado|location=Colorado, US|isbn=978-1-60732-048-7|page=445|edition=2nd}}</ref> and, except for the reindeer, only males have antlers.<ref name="Kingdon2013">{{cite book|last1=Kingdon|first1=J.|author1-link=Jonathan Kingdon|last2=Happold|first2=D.|last3=Butynski|first3=T.|last4=Hoffmann|first4=M.|last5=Happold|first5=M.|last6=Kalina|first6=J.|title=Mammals of Africa|volume=VI|date=2013|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|location=London, UK|isbn=978-1-4081-8996-2|page=116}}</ref> | |||

| Coat colour generally varies between red and brown,<ref name="mcshea">{{cite book|last1=Feldhamer|first1=G. A.|last2=McShea|first2=W. J.|title=Deer: The Animal Answer Guide|date=2012|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore, US|isbn=978-1-4214-0387-8|pages=1–142}}</ref> though it can be as dark as chocolate brown in the tufted deer<ref>{{cite book|last1=Francis|first1=C. M.|title=A Field Guide to the Mammals of South-East Asia|date=2008|publisher=New Holland|location=London, UK|isbn=978-1-84537-735-9|page=130}}</ref> or have a grayish tinge as in elk.<ref name=Kurta/> Different species of brocket deer vary from gray to reddish brown in coat colour.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Trolle|first1=M.|last2=Emmons|first2=L. H.|title=A record of a dwarf brocket from Lowland Madre De Dios, Peru|journal=Deer Specialist Group News|date=2004|issue=19|pages=2–5|url=https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/4762/VZ_lhe3.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y}}</ref> Several species such as the chital,<ref name="texas">{{cite book|last1=Schmidly|first1=D. J.|title=The Mammals of Texas|date=2004|publisher=University of Texas Press|location=Austin, Texas (US)|isbn=978-1-4773-0886-8|pages=263–4|edition=Revised|url=http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/cervaxis.htm}}</ref> the fallow deer<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hames|first1=D. S.|last2=Koshowski|first2=Denise|title=Hoofed Mammals of British Columbia|date=1999|publisher=UBC Press|location=Vancouver, Canada|isbn=978-0-7748-0728-9|page=113}}</ref> and the sika deer<ref>{{cite book|last1=Booy|first1=O.|last2=Wade|first2=M.|last3=Roy|first3=H.|title=Field Guide to Invasive Plants and Animals in Britain|date=2015|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|location=London, UK|isbn=978-1-4729-1153-7|page=170}}</ref> feature white spots on a brown coat. Coat of reindeer shows notable geographical variation.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Bowers|first1=N.|last2=Bowers|first2=R.|last3=Kaufmann|first3=K.|title=Mammals of North America|date=2004|publisher=Houghton Mifflin|location=New York, US|isbn=978-0-618-15313-8|pages=|url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780618153138/page/158}}</ref> Deer undergo two ]s in a year;<ref name=mcshea/><ref>{{cite book|last1=Hooey|first1=T.|title=Strategic Whitetail Hunting|date=2004|publisher=Krause Publications|isbn=978-1-4402-2702-8|page=39}}</ref> for instance, in red deer the red, thin-haired summer coat is gradually replaced by the dense, greyish brown winter coat in autumn, which in turn gives way to the summer coat in the following spring.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ryder|first1=M. L.|last2=Kay|first2=R. N. B.|title=Structure of and seasonal change in the coat of Red deer (''Cervus elaphus'')|journal=]|date=1973|volume=170|issue=1|pages=69–77|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1973.tb05044.x |issn=0952-8369 }}</ref> Moulting is affected by the ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lincoln|first1=G. A.|last2=Guinness|first2=F. E.|title=Effect of altered photoperiod on delayed implantation and moulting in roe deer|journal=]|date=1972|volume=31|issue=3|pages=455–7|doi=10.1530/jrf.0.0310455|pmid=4648129|url=http://www.reproduction-online.org/content/31/3/455.full.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.reproduction-online.org/content/31/3/455.full.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Deer are also excellent jumpers and swimmers. Deer are ]s, or cud-chewers, and have a four-chambered stomach. Some deer, such as those on the island of ],<ref name="Owen2003">{{cite news|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/08/0825_030825_carnivorousdeer.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030829000347/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/08/0825_030825_carnivorousdeer.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=29 August 2003|title=Scottish Deer Are Culprits in Bird Killings|last=Owen|first=James|date=25 August 2003|publisher=National Geographic News|access-date=16 June 2009}}</ref> do consume meat when it is available.<ref name="carniDeer">{{cite journal|first=Michael|last=Dale| title=Carnivorous Deer| journal=Omni Magazine|year=1988|page=31}}</ref> | |||

| Nearly all deer have a facial gland in front of each eye. The gland contains a strongly scented ], used to ] its home range. Bucks of a wide range of species open these glands wide when angry or excited. All deer have a ] without a ]. Deer also have a ], which gives them sufficiently good ]. | |||

| ===Antlers=== | |||

| {{main|Antler}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| All male deer have ]s, with the exception of the ], in which males have long tusk-like canines that reach below the lower jaw.<ref name="BurtonChinese">{{cite book|last1=Burton|first1=M.|last2=Burton|first2=R.|title=International Wildlife Encyclopedia|date=2002|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|location=New York, US|isbn=978-0-7614-7270-4|pages=|edition=3rd|url=https://archive.org/details/internationalwil04burt0/page/446}}</ref> Females generally lack antlers, though female reindeer bear antlers smaller and less branched than those of the males.<ref name="Hall2005">{{cite book|last1=Hall|first1=B. K.|title=Bones and Cartilage: Developmental and Evolutionary Skeletal Biology|date=2005|publisher=Elsevier Academic Press|location=Amsterdam, Netherlands|isbn=978-0-08-045415-3|pages=103–15|url={{Google Books|id=y-RWPGDONlIC|page=103|plainurl=yes}}}}</ref> Occasionally females in other species may develop antlers, especially in telemetacarpal deer such as European roe deer, red deer, white-tailed deer and mule deer and less often in plesiometacarpal deer. A study of antlered female white-tailed deer noted that antlers tend to be small and malformed, and are shed frequently around the time of parturition.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Wislocki|first1=G. B.|title=Antlers in female deer, with a report of three cases in ''Odocoileus''|journal=Journal of Mammalogy|date=1954|volume=35|issue=4|pages=486–95|jstor=1375571|doi=10.2307/1375571}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The fallow deer and the various subspecies of the reindeer have the largest as well as the heaviest antlers, both in absolute terms as well as in proportion to body mass (an average of eight grams per kilogram of body mass);<ref name="Hall2005" /><ref>{{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=T.|title=The Real Rudolph: A Natural History of the Reindeer|date=2013|publisher=The History Press|location=New York, US|isbn=978-0-7524-9592-7|url={{Google Books|id=MDA9AwAAQBAJ|page=PT18|plainurl=yes}}}}</ref> the tufted deer, on the other hand, has the smallest antlers of all deer, while the pudú has the lightest antlers with respect to body mass (0.6 g per kilogram of body mass).<ref name="Hall2005" /> The structure of antlers show considerable variation; while fallow deer and elk antlers are palmate (with a broad central portion), white-tailed deer antlers include a series of tines sprouting upward from a forward-curving main beam, and those of the pudú are mere spikes.<ref name="Geist" /> Antler development begins from the pedicel, a bony structure that appears on the top of the skull by the time the animal is a year old. The pedicel gives rise to a spiky antler the following year, that is replaced by a branched antler in the third year. This process of losing a set of antlers to develop a larger and more branched set continues for the rest of the life.<ref name="Hall2005" /> The antlers emerge as soft tissues (known as ]s) and progressively harden into bony structures (known as hard antlers), following ] and blockage of ]s in the tissue, from the tip to the base.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fletcher|first1=T. J.|editor1-last=Alexander|editor1-first=T. L.|editor2-last=Buxton|editor2-first=D.|title=Management and Diseases of Deer: A Handbook for the Veterinary Surgeon|date=1986|publisher=Veterinary Deer Society|location=London, UK|isbn=978-0-9510826-0-7|pages=17–8|edition=2nd|chapter=Reproduction: seasonality}}</ref> | |||

| ] fighting, ], India]] | |||

| Antlers might be one of the most exaggerated male ]s,<ref name="Malo">{{cite journal |doi=10.1098/rspb.2004.2933 |pmid=15695205 |pmc=1634960 |title=Antlers honestly advertise sperm production and quality |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume=272 |issue=1559 |pages=149–57 |year=2005 |last1=Malo |first1=A. F. |last2=Roldan |first2=E. R. S. |last3=Garde |first3=J. |last4=Soler |first4=A. J. |last5=Gomendio |first5=M. }}</ref> and are intended primarily for reproductive success through ] and for combat. The tines (forks) on the antlers create grooves that allow another male's antlers to lock into place. This allows the males to wrestle without risking injury to the face.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Emlen | first1=D. J. | year=2008 | title=The evolution of animal weapons | journal=Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics | volume=39 | pages=387–413 | doi=10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173502}}</ref> Antlers are correlated to an individual's position in the social hierarchy and its behaviour. For instance, the heavier the antlers, the higher the individual's status in the social hierarchy, and the greater the delay in shedding the antlers;<ref name=Hall2005/> males with larger antlers tend to be more aggressive and dominant over others.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bowyer|first1=R. T.|title=Antler characteristics as related to social status of male southern mule deer|journal=The Southwestern Naturalist|date=1986|volume=31|issue=3|pages=289–98|jstor=3671833|doi=10.2307/3671833}}</ref> Antlers can be an ] of genetic quality; males with larger antlers relative to body size tend to have increased resistance to ]s<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Ditchkoff | first1=S. S. | last2=Lochmiller | first2=R. L. | last3=Masters | first3=R. E. | last4=Hoofer | first4=S. R. | last5=Den Bussche | first5=R. A. Van | year=2001 | title=Major-histocompatibility-complex-associated variation in secondary sexual traits of white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus'') evidence for good-genes advertisement | journal=Evolution | volume=55 | issue=3| pages=616–625 | doi=10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00794.x | pmid=11327168| s2cid=10418779 | doi-access=free }}</ref> and higher reproductive capacity.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Malo | first1=A. F. | last2=Roldan | first2=E. R. S. | last3=Garde | first3=J. | last4=Soler | first4=A. J. | last5=Gomendio | first5=M. | year=2005 | title=Antlers honestly advertise sperm production and quality | journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences | volume=272 | issue=1559 | pages=149–157 | doi=10.1098/rspb.2004.2933 | pmid=15695205 | pmc=1634960}}</ref> | |||

| In elk in ], antlers also provide protection against predation by ].<ref name=wolves>{{cite journal |title=Predation shapes the evolutionary traits of cervid weapons |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |date=2018-09-03 |last1=Metz |first1=Matthew C. |last2=Emlen |first2=Douglas J. |last3=Stahler |first3=Daniel R. |last4=MacNulty |first4=Daniel R. |last5=Smith |first5=Douglas W. |volume=2 |issue=10 |pages=1619–1625 |doi=10.1038/s41559-018-0657-5 |pmid=30177803 |bibcode=2018NatEE...2.1619M |s2cid=52147419 }}</ref> | |||

| Homology of tines, that is, the branching structure of antlers among species, have been discussed before the 1900s.<ref>Garrod, A. Notes on the visceral anatomy and osteology of the ruminants, with a suggestion regarding a method of expressing the relations of species by means of formulae. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 2–18 (1877).</ref><ref>Brooke, V. On the classification of the Cervidæ, with a synopsis of the existing Species. Journal of Zoology 46, 883–928 (1878).</ref><ref>Pocock, R. The Homologies between the Branches of the Antlers of the Cervidae based on the Theory of Dichotomous Growth. Journal of Zoology 103, 377–406 (1933).</ref> Recently, a new method to describe the branching structure of antlers and determining homology of tines was developed.<ref>Samejima, Y., Matsuoka, H. A new viewpoint on antlers reveals the evolutionary history of deer (Cervidae, Mammalia). Sci Rep 10, 8910 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64555-7</ref> | |||

| ===Teeth=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Most deer bear 32 teeth; the corresponding ] is: {{DentalFormula|upper=0.0.3.3|lower=3.1.3.3}}. The elk and the reindeer may be exceptions, as they may retain their upper canines and thus have 34 teeth (dental formula: {{DentalFormula|upper=0.1.3.3|lower=3.1.3.3}}).<ref name="Reid">{{cite book|last1=Reid|first1=F. A.|title=A Field Guide to Mammals of North America, North of Mexico|date=2006|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Co.|location=Boston, US|isbn=978-0-395-93596-5|pages=153–4|edition=4th}}</ref> The Chinese water deer, tufted deer, and ] have enlarged upper ] forming sharp tusks, while other species often lack upper canines altogether. The cheek teeth of deer have crescent ridges of enamel, which enable them to grind a wide variety of vegetation.<ref name=EoM>{{cite book|editor-last= Macdonald|editor-first= D.|last= Cockerill|first= R.|year= 1984|title= The Encyclopedia of Mammals|publisher= Facts on File|location= New York, US|pages= |isbn= 978-0-87196-871-5|url= https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofma00mals_0/page/520}}</ref> The teeth of deer are adapted to feeding on vegetation, and like other ruminants, they lack upper ]s, instead having a tough pad at the front of their upper jaw. | |||

| ==Biology== | ==Biology== | ||

| Deer generally have lithe, compact bodies and long, powerful legs suited for rugged woodland terrain. Deer are also excellent swimmers. Deer are ]s, or cud-chewers, and have a four-chambered stomach. The teeth of deer are adapted to feeding on vegetation, and like other ruminants, they lack upper ]s, instead having a tough pad at the front of their upper jaw. The Chinese water deer and Tufted deer have enlarged upper ] teeth forming sharp tusks, while other species often lack upper canines altogether. The cheek teeth of deer have crescent ridges of enamel, which enable them to grind a wide variety of vegetation.<ref name=EoM>{{cite book |editor=Macdonald, D.|author= Cockerill, Rosemary|year=1984 |title= The Encyclopedia of Mammals|publisher= Facts on File|location=New York|pages= 520-529|isbn= 0-87196-871-1}}</ref> The ] for deer is:{{dentition2|0.0-1.3.3|3.1.3.3}} | |||

| ] browsing tree leaves in ], Sweden]] | |||

| Nearly all deer have a facial gland in front of each eye. The gland contains a strongly scented ], used to mark its home range. Bucks of a wide range of species open these glands wide when angry or excited. All deer have a ] without a ]. Deer also have a ] which gives them sufficiently good ]. | |||

| ===Diet=== | |||

| ] nursing young]] | |||

| A doe generally has one or two fawns at a time (triplets, while not unknown, are uncommon). The gestation period is anywhere up to ten months for the European ]. Most fawns are born with their fur covered with white spots, though they lose their spots once they get older (excluding the Fallow Deer who keeps its spots for life). In the first twenty minutes of a fawn's life, the fawn begins to take its first steps. Its mother licks it clean until it is almost free of scent, so predators will not find it. Its mother leaves often, and the fawn does not like to be left behind. Sometimes its mother must gently push it down with her foot. The fawn stays hidden in the grass for one week until it is strong enough to walk with its mother. The fawn and its mother stay together for about one year. A male usually never sees his mother again, but females sometimes come back with their own fawns and form small herds. | |||

| ] | |||

| Deer are ], and feed primarily on foliage of ], ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s, secondarily on ]s in northern latitudes during winter.<ref>Uresk, Daniel W., and Donald R. Dietz. "Fecal vs. Rumen Contents to Determine White-tailed Deer Diets." Intermountain Journal of Sciences 24, no. 3-4 (2018): 118–122.</ref> They have small, unspecialized stomachs by ] standards, and high nutrition requirements. Rather than eating and digesting vast quantities of low-grade fibrous food as, for example, ] and ] do, deer select easily digestible shoots, young leaves, fresh grasses, soft twigs, fruit, ], and ]s. The low-fibered food, after minimal fermentation and shredding, passes rapidly through the alimentary canal. The deer require a large amount of minerals such as ] and phosphate in order to support antler growth, and this further necessitates a nutrient-rich diet. There are some reports of deer engaging in carnivorous activity, such as eating dead ] along lakeshores<ref name=Case1987>{{cite journal |last1= Case |first1= D.J. |last2= McCullough |first2= D.R. |date= February 1987 |title= White-tailed deer forage on alewives |journal= Journal of Mammalogy |volume= 68 |issue= 1 |pages= 195–198 |doi= 10.2307/1381075|jstor= 1381075 }}</ref> or depredating the nests of ]s.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Ellis-Felege | first1 = S. N. | last2 = Burnam | first2 = J. S. | last3 = Palmer | first3 = W. E. | last4 = Sisson | first4 = D. C. | last5 = Wellendorf | first5 = S. D. | last6 = Thornton | first6 = R. P. | last7 = Stribling | first7 = H. L. | last8 = Carroll | first8 = J. P. | year = 2008 | title = Cameras identify White-tailed deer depredating Northern bobwhite nests| journal = Southeastern Naturalist | volume = 7 | issue = 3| pages = 562–564 | doi=10.1656/1528-7092-7.3.562| s2cid = 84790827 }}</ref> | |||

| Deer are selective feeders. They are usually ], and primarily feed on ]. They have small, unspecialized ]s by ] standards, and high nutrition requirements. Rather than attempt to digest vast quantities of low-grade, fibrous food as, for example, ] and ] do, deer select easily digestible shoots, young leaves, fresh ], soft ]s, ], ], and ]s. | |||

| === |

===Reproduction=== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| {{main|Rut (mammalian reproduction)#Cervidae}} | |||

| With the exception of the ], all male deer have ] that are shed and regrown each year from a structure called a pedicle. Sometimes a ] will have a small stub. The only female deer with antlers are ] (Caribou). Antlers grow as highly vascular spongy tissue covered in a skin called velvet. Before the beginning of a species' mating season, | |||

| ] nursing young]] | |||

| Nearly all cervids are so-called ] species: the young, known in most species as fawns, are only cared for by the mother, most often called a doe. A doe generally has one or two fawns at a time (triplets, while not unknown, are uncommon). Mating season typically begins in later August and lasts until December. Some species mate until early March. The ] is anywhere up to ten months for the European roe deer. Most fawns are born with their fur covered with white spots, though in many species they lose these spots by the end of their first winter. In the first twenty minutes of a fawn's life, the fawn begins to take its first steps. Its mother licks it clean until it is almost free of scent, so ]s will not find it. Its mother leaves often to graze, and the fawn does not like to be left behind. Sometimes its mother must gently push it down with her foot.<ref name="Ref_a"> Sheppard Software.</ref>{{better source needed|date=December 2020}} The fawn stays hidden in the grass for one week until it is strong enough to walk with its mother. The fawn and its mother stay together for about one year. A male usually leaves and never sees his mother again, but females sometimes come back with their own fawns and form small herds. | |||

| ===Disease=== | |||

| The one way that many hunters are able to track main paths that the deer travel on is because of their "rubs". A rub is used to deposit scent from glands near the eye and forehead and physically mark territory. | |||

| In some areas of the UK, deer (especially ] due to their ]) have been implicated as a possible reservoir for transmission of ],<ref name="Delahay et al., 2007">{{cite journal|last1=Delahay |first1=R. J. |last2=Smith |first2=G. C. |last3=Barlow |first3=A. M. |last4=Walker |first4=N. |last5=Harris |first5=A. |last6=Clifton-Hadley |first6=R. S. |last7=Cheeseman |first7=C. L. |year=2007 |title=Bovine tuberculosis infection in wild mammals in the South-West region of England: A survey of prevalence and a semi-quantitative assessment of the relative risks to cattle |journal=The Veterinary Journal |volume=173 |pages= 287–301 |pmid=16434219 |doi=10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.11.011 |issue=2}}</ref><ref name="Ward et al., 2009">{{cite journal |last1=Ward |first1=A. I. |last2=Smith |first2=G. C. |last3=Etherington |first3=T. R. |last4=Delahay |first4=R. J. |year=2009 |title=Estimating the risk of cattle exposure to tuberculosis posed by wild deer relative to badgers in England and Wales|pmid=19901384 |journal=Journal of Wildlife Diseases |volume= 45 |pages=1104–1120 |issue=4 |doi=10.7589/0090-3558-45.4.1104|s2cid=7102058 |doi-access=free }}</ref> a disease which in the UK in 2005 cost £90 million in attempts to eradicate.<ref name="The Vet Record, 2008">{{cite journal|author=Anonymous |year=2008|title=Bovine TB: EFRACom calls for a multifaceted approach using all available methods |journal=The Veterinary Record |volume=162 |pages=258–259 |pmid=18350673 |doi=10.1136/vr.162.9.258 |issue=9|s2cid=2429198}}</ref> In New Zealand, deer are thought to be important as vectors picking up ''M. bovis'' in areas where brushtail possums '']'' are infected, and transferring it to previously uninfected possums when their carcasses are scavenged elsewhere.<ref name="Delehay et al, 2002">{{cite journal |last1=Delahay |first1=R. J. |last2=De Leeuw |first2=A. N. S. |last3=Barlow |first3=A. M. |last4=Clifton-Hadley |first4=R. S. |last5=Cheeseman |first5=C. L. |year=2002 |title=The status of Mycobacterium bovis infection in UK wild mammals: A review |journal=The Veterinary Journal |volume=164 |pages=90–105 |pmid=12359464 |doi=10.1053/tvjl.2001.0667 |issue=2}}</ref> The white-tailed deer '']'' has been confirmed as the sole maintenance host in the Michigan outbreak of bovine tuberculosis which remains a significant barrier to the US nationwide eradication of the disease in livestock.<ref name="O'Brien et al., 2011">{{cite journal |last1=O'Brien |first1=D. J. |last2=Schmitt |first2=S. M. |last3=Fitzgerald |first3=S. D. |last4=Berry |first4=D. E. |year=2011 |title=Management of bovine tuberculosis in Michigan wildlife: Current status and near term prospects |pmid=21414734 |journal=Veterinary Microbiology |volume=151 |pages=179–187 |doi=10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.042 |issue=1–2|url=https://zenodo.org/record/1000720 }}</ref> Moose and deer can carry ].<ref name="mtt">{{cite news|publisher=Moncton Times&Transcript|title=Don't fraternize with wild animals: biologist|author=Alan Cochrane|date=January 2019}}</ref> | |||

| During the mating season, bucks use their antlers to fight one another for the opportunity to attract mates in a given herd. The two bucks circle each other, bend back their legs, lower their heads, and charge. | |||

| Docile moose may suffer from ], a ] which drills holes through the brain in its search for a suitable place to lay its eggs. A government biologist states that "They move around looking for the right spot and never really find it." Deer appear to be immune to this parasite; it passes through the digestive system and is excreted in the feces. The parasite is not screened by the moose intestine, and passes into the brain where damage is done that is externally apparent, both in behaviour and in gait.<ref name=mtt/> | |||

| Each species has its own characteristic antler structure, e.g. each white-tailed deer antler includes a series of tines sprouting upward from a forward-curving main beam. Mule deer (and black-tailed deer), species within the same genus as the white-tailed deer, instead have bifurcated (or branched) antlers -- that is, the main beam splits into two, each of which may split into two more. | |||

| Deer, elk and moose in North America may suffer from ], which was identified at a ] laboratory in the 1960s and is believed to be a prion disease. Out of an abundance of caution hunters are advised to avoid contact with ] (SRM) such as the brain, spinal column or lymph nodes. Deboning the meat when butchering and sanitizing the knives and other tools used to butcher are amongst other government recommendations.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/Hunt_Trap/deer/disease/cwdinformation.asp|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130514234545/http://www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/Hunt_Trap/deer/disease/cwdinformation.asp|url-status=dead|archive-date=2013-05-14|title=Wildlife and Heritage Service : Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD)|publisher=Maryland Department of Natural Resources}}</ref> | |||

| For ] and ], a stag having 14 points is an "imperial", and a stag having 12 points is a "royal". | |||

| If the antlers deviate from the species' normal antler structure, the deer is considered a non-typical deer. | |||

| ==Evolution== | |||

| The earliest fossil deer date from the ] of Europe, and resembled the modern ]s. Later species were often larger, with more impressive antlers, and, in many cases, lost of the upper canine teeth. They rapidly spread to the other continents, even for a time occupying much of northern Africa, where they are now almost wholly absent. Some extinct deer had huge antlers, larger than those of any living species. Examples include '']'', and the giant deer '']'', whose antlers stretched to 3.5 metres across. | |||

| Deer are believed to have evolved from antlerless, ]ed ancestors that resembled modern ]s and diminutive deer in the early ], and gradually developed into the first antlered cervoids (the ] of cervids and related extinct families) in the ]. Eventually, with the development of antlers, the tusks as well as the upper ]s disappeared. Thus, evolution of deer took nearly 30 million years. Biologist ] suggests evolution to have occurred in stages. There are not many prominent fossils to trace this evolution, but only fragments of skeletons and antlers that might be easily confused with false antlers of non-cervid species.<ref name="Geist">{{cite book | last1=Geist | first1=V. | author-link=Valerius Geist | title=Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behaviour and Ecology | date=1998 | publisher=Stackpole Books | location=Mechanicsburg, US | isbn=978-0-8117-0496-0 | pages=1–54 | edition=1st |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bcWZX-IMEVkC}}</ref><ref name=Goss1983/> | |||

| == Economic significance == | |||

| ]" by ].]] | |||

| Deer have long had economic significance to humans. Deer meat, for which they are ] and ]ed, is called ]. Deer organ meat is called ''umble''. See ]. | |||

| ===Eocene=== | |||

| ], which comes from the gland on the ] of ], is used in medicines and perfumes. Deerskin is used for shoes, boots, and gloves, and antlers are made into buttons and knife handles. | |||

| The ]s, ancestors of the Cervidae,<!--not sure how much we should say on this in this article--> are believed to have evolved from '']'', the earliest known artiodactyl (even-toed ungulate), 50–55 Mya in the Eocene.<ref name=Janis1998/> ''Diacodexis'', nearly the size of a ], featured the ] characteristic of all modern ]s. This ancestor and its relatives occurred throughout North America and Eurasia, but were on the decline by at least 46 Mya.<ref name="Janis1998">{{cite book | last1=Janis | first1=C. M. | last2=Effinger | first2=J. A. | last3=Harrison | first3=J. A. | last4=Honey | first4=J. G. | last5=Kron | first5=D. G. | last6=Lander | first6=B. | last7=Manning | first7=E. | last8=Prothero | first8=D. | author8-link=Donald Prothero | last9=Stevens | first9=M. S. | last10=Stucky | first10=R. K. | last11=Webb | first11=S. D. | last12=Wright | first12=D. B. | editor1-last=Janis | editor1-first=C. M. | editor2-last=Scott | editor2-first=K. M. | editor3-last=Jacobs | editor3-first=L. L. | title=Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America | url=https://archive.org/details/evolutiontertiar00jani_419 | url-access=limited | date=1998 | publisher=Cambridge University Press | location=Cambridge, UK | isbn=978-0-521-35519-3 | pages=–74 | edition=1st | chapter=Artiodactyla}}</ref><ref name="Heffelfinger">{{cite book | last1=Heffelfinger | first1=J. | title=Deer of the Southwest : A Complete Guide to the Natural History, Biology, and Management of Southwestern Mule Deer and White-tailed Deer | date=2006 | publisher=Texas A & M University Press | location=Texas, US | isbn=978-1-58544-515-8 | pages=1–57 | edition=1st |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AJnpJWzamN4C}}</ref> Analysis of a nearly complete skeleton of ''Diacodexis'' discovered in 1982 gave rise to speculation that this ancestor could be closer to the non-ruminants than the ruminants.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Rose | first1=K. D. | title=Skeleton of ''Diacodexis'', oldest known artiodactyl | journal=] | date=1982 | volume=216 | issue=4546 | pages=621–3 | doi=10.1126/science.216.4546.621 | pmid=17783306 | jstor=1687682| bibcode=1982Sci...216..621R | s2cid=13157519 }}</ref> '']'' is another prominent prehistoric ruminant, but appears to be closer to the ].<ref>{{cite book | editor1-last=Eldredge | editor1-first=N. | editor2-last=Stanley | editor2-first=S. M. | title=Living Fossils | date=1984 | publisher=Springer | location=New York, US | isbn=978-1-4613-8271-3}}</ref> | |||

| The ] of ] and the ] of ] and other nomadic peoples of northern ] used ] for food, clothing, and transport. | |||

| ===Oligocene=== | |||

| The ] is not domesticated or herded as is the case in ] but is important to the ]. Most commercial venison in the ] is imported from ]. | |||

| ]'']] | |||

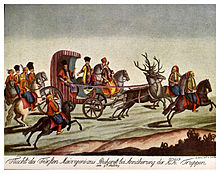

| ], ] ] of ], riding through ] in a deer−drawn carriage (late 1780s)]] | |||

| The formation of the ] and the ] brought about significant geographic changes. This was the chief reason behind the extensive diversification of deer-like forms and the emergence of cervids from the ] to the early ].<ref name=Ludt>{{cite journal | last1=Ludt | first1=C. J. | last2=Schroeder | first2=W. | last3=Rottmann | first3=O. | last4=Kuehn | first4=R. | title=Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') | journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution | date=2004 | volume=31 | issue=3 | pages=1064–83 | doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.003 | url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8585775 | pmid=15120401| bibcode=2004MolPE..31.1064L }}</ref> The latter half of the Oligocene (28–34 Mya) saw the appearance of the European '']'' and the North American '']''. The latter resembled modern-day bovids and cervids in dental morphology (for instance, it had ] molars), while the former was more ].<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Vislobokova | first1=I. | last2=Daxner-Höck | first2=G. | title=Oligocene–early Miocene ruminants from the Valley of Lakes (central Mongolia) | journal=Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien | date=2001 | volume=103 | pages=213–35 | jstor=41702231 | url=http://verlag.nhm-wien.ac.at/pdfs/103A_213235_Vislobokova.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160423034214/http://verlag.nhm-wien.ac.at/pdfs/103A_213235_Vislobokova.pdf |archive-date=2016-04-23 |url-status=live }}</ref> Other deer-like forms included the North American '']'' and the European '']''; these sabre-toothed animals are believed to have been the direct ancestors of all modern antlered deer, though they themselves lacked antlers.<ref name="Stirton">{{cite journal | last1=Stirton | first1=R. A. | title=Comments on the relationships of the cervoid family Palaeomerycidae | journal=American Journal of Science | date=1944 | volume=242 | issue=12 | pages=633–55 | doi=10.2475/ajs.242.12.633| bibcode=1944AmJS..242..633S | doi-access=free }}</ref> Another contemporaneous form was the four-horned ] '']'', that was replaced by '']'' in the Miocene; these animals were unique in having a horn on the nose.<ref name=Goss1983/> Late Eocene fossils dated approximately 35 million years ago, which were found in North America, show that ''Syndyoceras'' had bony skull outgrowths that resembled non-deciduous antlers.<ref name=agate>{{cite book | publisher=Interior Department, National Park Service, Division of Publications | title=Agate Fossil Beds: Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska | date= February 1989| isbn=978-0-912627-04-5 | page=31}}</ref> | |||

| Deer were originally brought to ] by European settlers, and the deer population rose rapidly. This caused great environmental damage and was controlled by hunting and poisoning until the concept of deer farming developed in the 1960s. Deer farms in New Zealand number more than 3,500, with more than 400,000 deer in all. | |||

| ===Miocene=== | |||

| Automobile collisions with deer impose a significant cost on the economy. In the U.S., about 1.5 million deer-vehicle collisions occur each year, according to the ]. Those accidents cause about 150 deaths and $1.1 billion in property damage annually. | |||

| Fossil evidence suggests that the earliest members of the superfamily Cervoidea appeared in Eurasia in the Miocene. '']'', '']'' and '']'' were probably the first antlered cervids.<ref name="Gentry1994">{{cite journal | last1=Gentry | first1=A. W. | last2=Rössner | first2 = G. | title=The Miocene differentiation of Old World Pecora (Mammalia) | journal=Historical Biology | date=1994 | volume=7 | issue=2 | pages=115–58 | doi=10.1080/10292389409380449| bibcode=1994HBio....7..115G }}</ref> ''Dicrocerus'' featured single-forked antlers that were shed regularly.<ref name=Azanza>{{cite journal | last1=Azanza | first1=B. | last2=DeMiguel | first2=D. | last3=Andrés | first3=M. | title=The antler-like appendages of the primitive deer ''Dicrocerus elegans'': morphology, growth cycle, ontogeny, and sexual dimorphism | journal=Estudios Geológicos | date=2011 | volume=67 | issue=2 | pages=579–602 | doi=10.3989/egeol.40559.207| doi-access=free }}</ref> '']'' had more developed and diffuse ("crowned") antlers.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Wang | first1=X. | last2=Xie | first2=G. | last3=Dong | first3=W. | title=A new species of crown-antlered deer ''Stephanocemas'' (Artiodactyla, Cervidae) from the middle Miocene of Qaidam Basin, northern Tibetan Plateau, China, and a preliminary evaluation of its phylogeny | journal=Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society | date=2009 | volume=156 | issue=3 | pages=680–95 | doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00491.x | url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230071825| doi-access=free }}</ref> '']'' (]) also had antlers that were not shed.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Ginsburg | first1=L. | title=La faune des mammifères des sables Miocènes du synclinal d'Esvres (Val de Loire) | journal=Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences | date=1988 | pages=319–22 | series=II | trans-title=The mammalian fauna of the Miocene sands of the syncline Esvres (Loire Valley) | language=fr}}</ref> Contemporary forms such as the ]s eventually gave rise to the modern pronghorn.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Walker | first1=D. N. | title=Pleistocene and Holocene records of ''Antilocapra americana'': a review of the FAUNMAP data | journal=Plains Anthropologist | date=2000 | volume=45 | issue=174 | pages=13–28 | jstor=25669684 | url=http://www.uwyo.edu/anthropology/_files/docs/walker/48%20walker%202000%20pleistocene%20records%20antilocapra%202.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.uwyo.edu/anthropology/_files/docs/walker/48%20walker%202000%20pleistocene%20records%20antilocapra%202.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live| doi=10.1080/2052546.2000.11932020 | s2cid=163903264 }}</ref> | |||

| == Taxonomy== | |||

| Note that the terms indicate the origin of the groups, not their modern distribution: the ], for example, is a New World species but is found only in ] and ]. | |||

| The Cervinae emerged as the first group of extant cervids around 7–9 Mya, during the late Miocene in central Asia. The tribe Muntiacini made its appearance as ] '']'' around 7–8 Mya;<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Dong | first1=W. | last2=Pan | first2=Y. | last3=Liu | first3=J. | title=The earliest ''Muntiacus'' (Artiodactyla, Mammalia) from the Late Miocene of Yuanmou, southwestern China | journal=Comptes Rendus Palevol | date=September 2004 | volume=3 | issue=5 | pages=379–86 | doi=10.1016/j.crpv.2004.06.002 | bibcode=2004CRPal...3..379D | url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232743453}}</ref> The early muntjacs varied in size–as small as hares or as large as fallow deer. They had tusks for fighting and antlers for defence.<ref name=Geist/> Capreolinae followed soon after; Alceini appeared 6.4–8.4 Mya.<ref name=Gilbert2006/> Around this period, the ] disappeared to give way to vast stretches of grassland; these provided the deer with abundant protein-rich vegetation that led to the development of ornamental antlers and allowed populations to flourish and colonise areas.<ref name=Geist/><ref name=Ludt/> As antlers had become pronounced, the canines were either lost or became poorly represented (as in elk), probably because diet was no longer ]-dominated and antlers were better display organs. In muntjac and tufted deer, the antlers as well as the canines are small. The tragulids have long canines to this day.<ref name=Heffelfinger/> | |||

| It is thought that the new world group evolved about 5 million years ago in the forests of ] and ], the old world deer in ]. | |||

| ===Pliocene=== | |||

| === Subfamilies, genera and species === | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| The family Cervidae is organized as follows: | |||

| With the onset of the ], the global climate became cooler. A fall in the sea-level led to massive glaciation; consequently, grasslands abounded in nutritious forage. Thus a new spurt in deer populations ensued.<ref name=Geist/><ref name=Ludt/> The oldest member of Cervini, ] '']'', appeared around the transition from Miocene to Pliocene (4.2–6 Mya) in Eurasia;<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Di Stefano | first1=G. | last2=Petronio | first2=C. | title=Systematics and evolution of the Eurasian Plio-Pleistocene tribe Cervini (Artiodactyla, Mammalia) | journal=Geologica Romana | date=2002 | volume=36 | pages=311–34 | url=http://tetide.geo.uniroma1.it/dst/grafica_nuova/pubblicazioni_DST/geologica_romana/Volumi/VOL%2036/GR_36_311_334_DI%20Stefano%20et%20al.pdf | access-date=11 April 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160310214846/http://tetide.geo.uniroma1.it/dst/grafica_nuova/pubblicazioni_DST/geologica_romana/Volumi/VOL%2036/GR_36_311_334_DI%20Stefano%20et%20al.pdf | archive-date=10 March 2016 | url-status=dead }}</ref> cervine fossils from early Pliocene to as late as the ] have been excavated in China<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Petronio | first1=C. | last2=Krakhmalnaya | first2=T. | last3=Bellucci | first3=L. | last4=Di Stefano | first4=G. | title=Remarks on some Eurasian pliocervines: Characteristics, evolution, and relationships with the tribe Cervini | journal=Geobios | date=2007 | volume=40 | issue=1 | pages=113–30 | doi=10.1016/j.geobios.2006.01.002| doi-access=free | bibcode=2007Geobi..40..113P }}</ref> and the Himalayas.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Ghaffar | first1=A. | last2=Akhtar | first2=M. | last3=Nayyer | first3=A. Q. | title=Evidences of Early Pliocene fossil remains of tribe Cervini (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Cervidae) from the Siwaliks of Pakistan | journal=Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences | date=2011 | volume=21 | issue=4 | pages=830–5 | url=http://www.thejaps.org.pk/docs/21-4/34.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.thejaps.org.pk/docs/21-4/34.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live}}</ref> While ''Cervus'' and ''Dama'' appeared nearly 3 Mya, ''Axis'' emerged during the late Pliocene–Pleistocene. The tribes Capreolini and Rangiferini appeared around 4–7 Mya.<ref name=Gilbert2006/> | |||

| *Subfamily '''Muntiacinae''' (]s) | |||

| **Genus ''Muntiacus'': | |||

| ***] or Common Muntjac (''Muntiacus muntjak'') | |||

| ***] or Chinese Muntjac (''Muntiacus reevesi'') | |||

| ***] or Black Muntjac (''Muntiacus crinifrons'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus feae'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus atherodes'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus rooseveltorum'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus gongshanensis'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus vuquangensis'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus truongsonensis'') | |||

| ***] (''Muntiacus putaoensis'') | |||

| **Genus ''Elaphodus'': | |||

| ***] (''Elaphodus cephalophus'') | |||

| *Subfamily '''Cervinae''' (True Deer, Old World Deer): | |||

| **Genus ''Cervus'': | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Cervus'': | |||

| ****European ] (''Cervus elaphus'') | |||

| ****] (''Cervus wallichi'') | |||

| ****] (''Cervus canadensis'') (North American and Asian Elk; second largest deer in world; not to be confused with Moose, known as Elk in Europe) | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Przewalskium'': | |||

| ****], or ] (''Cervus albirostris'') | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Sika'': | |||

| ****] (''Cervus nippon'') | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Rucervus'': | |||

| ****] (''Cervus duvaucelii'') | |||

| ****] (''Cervus schomburgki'') (], 1938) | |||

| ****] or ] (''Cervus eldii'') | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Rusa'': | |||

| ****Indian ] (''Cervus unicolor'') | |||

| ****] or ] (''Cervus timorensis'') | |||

| ****] (''Cervus mariannus'') | |||

| ****] or ] (''Cervus alfredi'') (smallest Old World deer) | |||

| **Genus ''Axis'': | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Axis'': | |||

| ****] or ] (''Axis axis'') | |||

| ***Subgenus ''Hyelaphus'': | |||

| ****] (''Axis porcinus'') | |||

| ****] (''Axis calamianensis'') | |||

| ****] (''Axis kuhlii'') | |||

| **Genus ''Elaphurus'': | |||

| ***] (''Elaphurus davidianus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Dama'': | |||

| ***] (''Dama dama'') | |||

| ***] (''Dama mesopotamica'') | |||

| ***] (''Megaloceros giganteus'') †<ref name=giant_deer> Letter in ''Nature'' 438, 850-853 (8 December 2005)</ref> | |||

| ], the smallest species of deer in the world]] | |||

| *Subfamily '''Hydropotinae''' (Water Deer) | |||

| **Genus ''Hydropotes'': | |||

| ***] (''Hydropotes inermis'') | |||

| *Subfamily '''Odocoileinae/Capreolinae''' (New World Deer) | |||

| **Genus ''Odocoileus'': | |||

| ***] (''Odocoileus virginianus'') | |||

| ***], or Black-tailed deer (''Odocoileus hemionus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Blastocerus'': | |||

| ***] (''Blastocerus dichotomus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Ozotoceros'': | |||

| ***] (''Ozotoceros bezoarticus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Mazama'': | |||

| ***] (''Mazama americana'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama bricenii'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama chunyi'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama gouazoubira'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama nana'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama pandora'') | |||

| ***] (''Mazama rufina'') | |||

| **Genus ''Pudu'': | |||

| ***] (''Pudu mephistophiles'') (smallest deer in the world) | |||

| ***Southern ] (''Pudu pudu'') | |||

| **Genus ''Hippocamelus'': | |||

| ***] or ] (''Hippocamelus antisensis'') | |||

| ***] or ] (''Hippocamelus bisulcus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Capreolus'': | |||

| ***European ] (''Capreolus capreolus'') | |||

| ***] (''Capreolus pygargus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Rangifer'': | |||

| ***] (''Rangifer tarandus'') | |||

| **Genus ''Alces'': | |||

| ***] (''Alces alces''; called "Elk" in England and Scandinavia) (largest deer in the world) | |||

| Around 5 Mya, the rangiferina ] '']'' and ] '']'' were the first cervids to reach North America.<ref name=Gilbert2006/> This implies the Bering Strait could be crossed during the late Miocene–Pliocene; this appears highly probable as the ]s migrated into Asia from North America around the same time.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=van der Made | first1=J. | last2=Morales | first2=J. | last3=Sen | first3=S. | last4=Aslan | first4=F. | title=The first camel from the Upper Miocene of Turkey and the dispersal of the camels into the Old World | journal=Comptes Rendus Palevol | date=2002 | volume=1 | issue=2 | pages=117–22 | doi=10.1016/S1631-0683(02)00012-X| bibcode=2002CRPal...1..117V }}</ref> Deer invaded South America in the late Pliocene (2.5–3 Mya) as part of the ], thanks to the recently formed ], and emerged successful due to the small number of competing ruminants in the continent.<ref>{{cite book | last1=Webb | first1=S. D. | editor1-last=Vrba | editor1-first=E. S. | editor1-link=Elisabeth Vrba | editor2-last=Schaller | editor2-first=G. B. | editor2-link=George Schaller | title=Antelopes, Deer, and Relatives: Fossil Record, Behavioral Ecology, Systematics, and Conservation | date=2000 | publisher=Yale University Press | location=New Haven, US | isbn=978-0-300-08142-8 | pages=38–64 | chapter=Evolutionary history of New World Cervidae |chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=f34SmXP27ywC&pg=PA38}}</ref> | |||

| === Hybrid deer === | |||

| ===Pleistocene=== | |||

| In '']'' (1859) ] wrote "Although I do not know of any thoroughly well-authenticated cases of perfectly fertile hybrid animals, I have some reason to believe that the hybrids from Cervulus vaginalis and Reevesii are perfectly fertile." These two varieties of muntjac are currently considered the same species. | |||

| Large deer with impressive antlers evolved during the early Pleistocene, probably as a result of abundant resources to drive evolution.<ref name=Geist/> The early Pleistocene cervid ] '']'' was comparable in size to the modern elk.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=De Vos | first1=J. | last2=Mol | first2=D. | last3=Reumer | first3=J. W. F. | title=Early Pleistocene Cervidae (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from the Oosterschelde (the Netherlands), with a revision of the cervid genus ''Eucladoceros'' Falconer, 1868 | journal=Deinsea | date=1995 | issue=2 | pages=95–121 | url=http://www.hetnatuurhistorisch.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/documents-nmr/Publicaties/Deinsea/Deinsea_02/Deinsea_2_p95-121_de_Vos.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.hetnatuurhistorisch.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/documents-nmr/Publicaties/Deinsea/Deinsea_02/Deinsea_2_p95-121_de_Vos.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] '']'' (Pliocene–Pleistocene) featured the ] (''M. giganteus''), one of the ]. The Irish elk reached {{convert |2|m|ft|frac=2}} at the shoulder and had heavy antlers that spanned {{convert|3.6|m|ftin}} from tip to tip.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Lister | first1=A. M. | last2=Gonzalez | first2=S. | last3=Kitchener | first3=A. C. | title=Survival of the Irish elk into the Holocene | journal=] | date=2000 | volume=405 | issue=6788 | pages=753–4 | doi=10.1038/35015668 | pmid=10866185| bibcode=2000Natur.405..753G | s2cid=4417046 }}</ref> These large animals were traditionally thought to have faced extinction due to conflict between ] for large antlers and body and ] for a smaller form,<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Moen | first1=R. A. | last2=Pastor | first2=J. | last3=Yosef | first3=C. | title=Antler growth and extinction of Irish elk | journal=Evolutionary Ecology Research | date=1999 | issue=1 | pages=235–49 | url=http://www.duluth.umn.edu/~rmoen/Dld/Moen_1999.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029193608/http://www.duluth.umn.edu/~rmoen/Dld/Moen_1999.pdf |archive-date=2013-10-29 |url-status=live}}</ref> but a combination of anthropogenic and climatic pressures is now thought to be the most likely culprit.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lister |first1=Adrian M. |last2=Stuart |first2=Anthony J. |date=2019-01-01 |title=The extinction of the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach): New radiocarbon evidence |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618219300333 |journal=Quaternary International |series=SI: Quaternary International 500 |volume=500 |pages=185–203 |doi=10.1016/j.quaint.2019.03.025 |bibcode=2019QuInt.500..185L |issn=1040-6182}}</ref> Meanwhile, the moose and reindeer radiated into North America from Siberia.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Breda | first1=M. | last2=Marchetti | first2=M. | title=Systematical and biochronological review of Plio-Pleistocene Alceini (Cervidae; Mammalia) from Eurasia | journal=Quaternary Science Reviews | date=2005 | volume=24 | issue=5–6 | pages=775–805 | doi=10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.05.005| bibcode=2005QSRv...24..775B | url=http://doc.rero.ch/record/209798/files/PAL_E4211.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://doc.rero.ch/record/209798/files/PAL_E4211.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| A number of deer hybrids are bred to improve meat yield in farmed deer. American Elk (or Wapiti) and Red Deer from the Old World can produce fertile offspring in captivity, and were once considered one species. Hybrid offspring, however, must be able to escape and defend themselves against predators, and these hybrid offspring are unable to do so in the wild state. Recent DNA, animal behavior studies, and morphology and antler characteristics have shown there are not one but three species of Red Deer: European ], ], and American Elk or Wapiti. (The European Elk is a different species and is known as ] in North America.) The hybrids are about 30% more efficient in producing antler by comparing velvet to body weight. Wapiti have been introduced into some European Red Deer herds to improve the Red Deer type, but not always with the intended improvement. | |||

| ==Taxonomy and classification== | |||

| In New Zealand, where deer are introduced species, there are hybrid zones between Red Deer and North American Wapiti populations and also between Red Deer and Sika Deer populations. In New Zealand Red Deer have been artificially hybridized with Pere David Deer in order to create a farmed deer which gives birth in spring. The initial hybrids were created by artificial insemination and back-crossed to Red Deer. However, such hybrid offspring can only survive in captivity free of predators. | |||

| {{Further|List of cervids}} | |||

| In Canada, the farming of European Red Deer and Red Deer hybrids is considered a threat to native Wapiti. In Britain, the introduced Sika Deer is considered a threat to native Red Deer. Initial Sika Deer/Red Deer hybrids occur when young Sika stags expand their range into established red deer areas and have no Sika hinds to mate with. They mate instead with young Red hinds and produce fertile hybrids. These hybrids mate with either Sika or Red Deer (depending which species is prevalent in the area), resulting in mongrelization. Many of the Sika Deer which escaped from British parks were probably already hybrids for this reason. These hybrids do not properly inherit survival strategies and can only survive in either a captive state or when there are no predators. | |||

| ] | |||

| Deer constitute the ] ] Cervidae. This family was first ] by German zoologist ] in ''Handbuch der Zoologie'' (1820). Three ] were recognised: Capreolinae (first described by the English zoologist ] in 1828), Cervinae (described by Goldfuss) and Hydropotinae (first described by French zoologist ] in 1898).<ref name=Groves2007>{{cite book | last1=Groves | first1=C. | author-link1=Colin Groves | chapter=Family Cervidae | chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qO8H_alEofAC&pg=PA249 | editor1-last=Prothero | editor1-first=D. R. | editor1-link=Donald Prothero | editor2-last=Foss | editor2-first=S. E. | title=The Evolution of Artiodactyls | date=2007 | publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press | location=Baltimore, US | isbn=978-0-801-88735-2 | pages=249–56 | edition=Illustrated}}</ref><ref name=MSW3>{{MSW3 | id=14200205 | page=652–70}}</ref> | |||

| Other attempts at the classification of deer have been based on morphological and ] differences.<ref name="Goss1983">{{cite book | first1=R. J. | last1=Goss | title=Deer Antlers Regeneration, Function and Evolution | date=1983 | publisher=Elsevier | location=Oxford, UK | isbn=9780323140430 | pages=43–51}}</ref> The Anglo-Irish naturalist ] suggested in 1878 that deer could be bifurcated into two classes on the according to the features of the second and fifth ]s of their forelimbs: Plesiometacarpalia (most Old World deer) and Telemetacarpalia (most New World deer). He treated the ] as a cervid, placing it under Telemetacarpalia. While the telemetacarpal deer showed only those elements located far from the joint, the plesiometacarpal deer retained the elements closer to the joint as well.<ref name="Brooke1878">{{cite journal | last1=Brooke | first1=V. | title=On the classification of the Cervidœ, with a synopsis of the existing species | journal=] | date=1878 | volume=46 | issue=1 | pages=883–928 | doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1878.tb08033.x| url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/73538 }}</ref> Differentiation on the basis of ] number of ]s in the late 20th century has been flawed by several inconsistencies.<ref name=Goss1983/> | |||

| In captivity, Mule Deer have been mated to White-tail Deer. Both male Mule Deer/female White-tailed Deer and male White-tailed Deer/female Mule Deer matings have produced hybrids. Less than 50% of the hybrid fawns survived their first few months. Hybrids have been reported in the wild but are disadvantaged because they don't properly inherit survival strategies. Mule Deer move with bounding leaps (all 4 hooves hit the ground at once, also called "stotting") to escape predators. Stotting is so specialized that only 100% genetically pure Mule Deer seem able to do it. In captive hybrids, even a one-eighth White-tail/seven-eighths Mule Deer hybrid has an erratic ] and would be unlikely to survive to breeding age. Hybrids do survive on game ranches where both species are kept and where predators are controlled by man. | |||